Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Outdoors in RI: Help keep recreation areas clean. Invasive Milfoil, trash. 2A update – Jeff Gross July 26, 2024

- Real Estate in RI: Highest-ever sale in Queen’s Grant, EG $1.25M, by Residential Properties July 26, 2024

- Homeless in RI: Gov. Newsom issues Executive Order. Remove California’s encampments. July 26, 2024

- Let the games begin. XXXIII Summer Olympics – John Cardullo July 26, 2024

- GriefSPEAK: What would you do? – Mari Dias Nardolillo July 26, 2024

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

The College Hill Study, part 1, Lost Providence – David Brussat

by David Brussat, Architecture Here and There, contributing writer

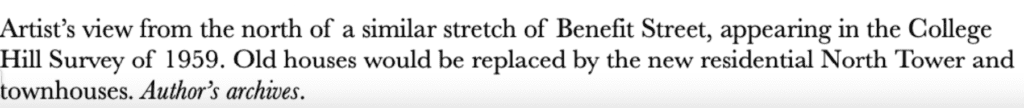

Photo:

This is the first half of the second chapter in this series, which reprints segments from Part II of Lost Providence, published in 2017 by History Press. Chapter 16, “The College Hill Study,” looks at how the city intended to “preserve” College Hill using methodologies meant to designate for slum clearance areas that history shows were eminently suitable for preservation and sale by private interests.

***

While city officials, federal bureaucrats and business leaders were preparing the plan to save downtown Providence by destroying it, another massive redevelopment proposal emerged alongside the Downtown Providence 1970 plan. It was based on a study called “College Hill: A Demonstration Study of Historic Area Renewal,” actually announced in June 1959, a year before the downtown plan. In the plan to save the city’s fabled College Hill, the recently founded Providence Preservation Society joined hands with the City Plan Commission and the U.S.Urban Renewal Administration.

The planning stages for both plans overlapped, as did some project staff, including William D. Warner, who worked briefly for the downtown plan but was project director of the College Hill study. Both positions were among his first jobs after graduating in 1957 with bachelor’s and master’s degrees in architecture from MIT. Members of the City Plan Commission took part in both plans. State planning officials seem to have been largely uninvolved in either, or at least unrepresented and unacknowledged in the lists of contributors, sponsoring agencies, task force members and such that commence each plan.

The motive, at least as far as the College Hill plan’s historical reputation is concerned, was to preserve Benefit Street and nearby streets from demolition and to institute an administrative infrastructure to protect College Hill going forward.

Both of those goals have been achieved in spectacular fashion. Since 1960, almost no historical buildings on Benefit Street and its residential environs have been knocked down. Within two decades, Benefit Street itself became fashionable, unapproachably so for most families. Following the enactment of federal enabling legislation, the General Assembly created the Rhode island Historical Preservation Commission to oversee a state historic preservation office to establish, survey and monitor developments in historical districts statewide. (The words “and heritage” were added after the Rhode Island Heritage Commission was merged with the RIPHPC.) The Providence Preservation Society was founded in 1956 and became one of the nation’s pre-eminent preservationist organizations, lobbying to save the city’s architectural heritage through government bodies it was itself instrumental in creating.

The College Hill study fails, on one hand, to identify any imminent threat of large-scale demolition on Benefit or its environs. On the other hand, from page 101 of the study, “Previous Planning studies,” it is clear that the idea of tearing down parts of Benefit Street had been circulating amid various local and state agencies since 1945, if not before. After mentioning a number of these instances, the section cites “basic statistics” that point to “some degree of housing blight. Approximately 140 acres, or 35% of the College Hill study area, is included within two of the 17 Redevelopment Areas designated by City Council action in July 1948.” The report adds that in 1951, “three proposals … have been the subject of serious review: (1) South Main, (2) Cohan Boulevard, and (3) Constitution Hill. None of these are currently active.”

This is not to suggest that fears of wholesale demolition on Benefit Street were unwarranted. After all, before the study, in the early 1950s, Brown University had razed a couple score of old houses to create its Henry Wriston residential quadrangle. (Fortunately, its design, unlike most later buildings at Brown, was sympathetic with its historic institutional character.) Opposition to that project’s demolitions germinated the Providence Preservation Society and led to its participation in the College Hill study.

Within a few years of the study’s release, major urban removal and insensitive redevelopment occurred in Weybosset Hill downtown, spurred by the 1970 plan, and in Lippitt Hill for University Heights. The latter was a private project designed by noted shopping center designer Victor Gruen that combined shopping and a residential center just north of the College Hill study area. This obliterated parts of a black neighborhood once called Hardscrabble, where a race riot erupted in 1824 (another race riot occurred in Snowtown, a black neighborhood on the east slope of Smith Hill, in 1831).

In fact, urban removal is still happening on College Hill. Two sets of deteriorating but clearly useful old houses, sixteen in all, on or near Thayer Street (Brown’s “main street”) were recently razed, one for a private graduate housing complex, the other for a “temporary” parking lot. “Demolition by neglect” is the common term given to this process, which may have played a role before 1959 in the deterioration of housing at either end of Benefit Street.

Yet it is reasonable to suggest that the federal definitions of slum housing that influenced the College Hill study’s expansive plans for new development were wildly out of sync with reality – although perfectly simpatico with the conventional wisdom of the postwar architectural and development establishments. It is not difficult to suppose that much housing labeled substandard was so designated in order to justify tearing it down. Assumptions regarding the economic and social benefits of “slum clearance” trickled down from federal to local agencies and hardened into dogma.

Perhaps the most famous victim of this policy trend was the West End of Boston, a vibrant neighborhood of mostly Italian and Jewish immigrants that was replaced with residential high-rises for middle- and upper-middle-class families. Part of Boston’s North End was razed to make way for the Central Artery, an elevated highway that sliced between downtown Boston and its harbor. Other sections of the North End were also threatened with demolition but spared; today, the North End’s good health points a stern finger at the policies that doomed the West End.

And Boston’s Scollay Square was demolished for a new city hall and federal government center designed in the Brutalist style used more modestly in Providence’s Fogarty Building (see chapter 6). The public in Boston has been clamoring for City Hall’s demolition for years. In 2006, Mayor Thomas Menino proposed razing the monstrosity, but he never followed through.

The wholesale demolition of historic settings around the nation was typically followed by an urbanism designed not to engage but to rebuke the historic settings that remained nearby. Urban renewal blighted many downtowns and is continuing to do so, though at a much diminished rate today: thanks to the preservation movement generated by the widespread anxiety caused by urban renewal and modern architecture. Jane Jacobs examined and sharply criticized planning practices that had grown common in the 1950s in her 1961 bestseller The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

Almost all of the College Hill housing labeled “slum” or “substandard” by the study and slated for renewal was later privately repaired, restored and sold to private buyers. This happened largely outside the context of the College Hill study and its seemingly precise methods of surveying and assessing the quality of housing stock. The study devotes several sections to explaining the opportunity for private investment by individuals and groups in the restoration and renovation of dilapidated properties:

It is recommended that attempts be made to stimulate private investment in College Hill by alerting certain individuals and groups to the opportunities for investment in the area. Stimulation of the investment of private capital to renew the historic College Hill area is one of the goals of the proposed program.

The second edition of the study, published in 1967, has a Part IV that addresses its impact, called “Progress since 1959,” noting that private investment had been substantially stimulated:

Publication of the study report, the publicity given to it, and the support of city agencies did much to generate confidence in the area and to change the attitudes of mortgage agencies to investment in this older section of the city. Several private companies were organized for the purchase and restoration of historic buildings.

So the study did give brief encouragement – lip service, some might say – to the private investment and rehabilitation strategy that almost totally eclipsed the study’s urban-renewal strategy. Perhaps it is only fair to give some credit to the study for not entirely dismissing a far more effective and far more obvious course of action. But it is also fair to wonder how much of the subsequent several decades of private activity was stimulated, contrarily, by local fears of what the study proposed for College Hill. Was the study’s proposal to erect two residential towers of nineteen and twenty-two stories at either end of Benefit Street likely to allay such fears? The question answers itself.

***

The second half of Chapter 16, “The College Hill Study,” will appear in the next post on this blog. It will include a detailed examination of the foundation for claims that much of College Hill was unworthy of preserving.

___

To read other articles by David Brussat: https://rinewstoday.com/david-brussat-contributing-writer/

My freelance writing and editing on architecture and others addresses issues of design and culture locally and globally. I am a member of the board of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which bestowed an Arthur Ross Award on me in 2002. I work from Providence, R.I., where I live with my wife Victoria, my son Billy and our cat, Gato. If you would like to employ my writing and editing to improve your work, please email me at my consultancy, [email protected], or call (401) 351-0451