Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Outdoors in RI: Help keep recreation areas clean. Invasive Milfoil, trash. 2A update – Jeff Gross July 26, 2024

- Real Estate in RI: Highest-ever sale in Queen’s Grant, EG $1.25M, by Residential Properties July 26, 2024

- Homeless in RI: Gov. Newsom issues Executive Order. Remove California’s encampments. July 26, 2024

- Let the games begin. XXXIII Summer Olympics – John Cardullo July 26, 2024

- GriefSPEAK: What would you do? – Mari Dias Nardolillo July 26, 2024

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

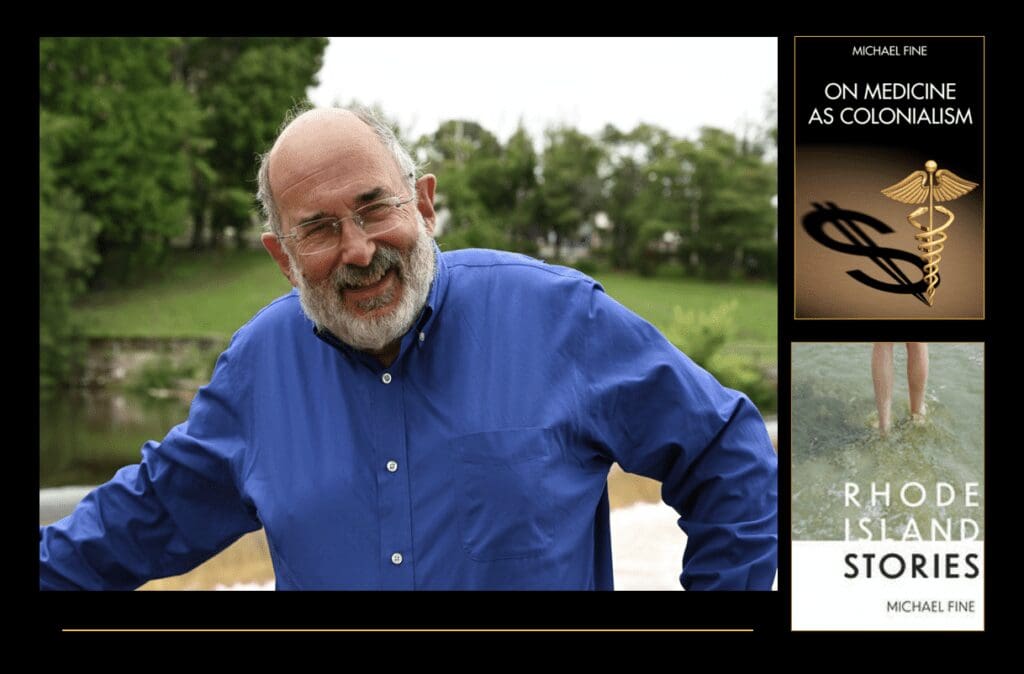

Short Story: The Sad and Lonely Death of Katydid Desrosiers (6) – Michael Fine

Week Six

Note to readers: This story is longer than most I’ve written, so we’re going to send out one section a week over the next six weeks – and we’ve included a brief summary of what’s been sent so far to catch you up in case you missed prior weeks. I’d suggest starting it on your cell, and if you like what you see, consider downloading it and printing it out — it’s a little long to read cramped over a tiny little screen. It’s available for printout on https://www.michaelfinemd.com/short-stories.

The influence of Leo Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Illich will be apparent to many readers, and is gratefully, and humbly, acknowledged.

Copyright © 2023 Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

–

In Week One, we met Katy Desrosiers, a woman who is living in her car, an old green Saturn with one white door, and learn a little about how she lives. She moves the car from place to place and parks it at night where she isn’t likely to be noticed. She spends her days walking, to libraries and to parks to stay warm, but also so she won’t be noticed. We also meet Vernon Jenkins, who lives in Lincoln, in one of the places Katy parks her car some nights. We learn that Katy was born in Rutherford, New Jersey, just over the Hudson River from New York City, and was a singer. Then we meet a woman who is a television anchor and was a newspaper reporter, who notices Katy’s car, and remembers she one had a car like Katy’s.

In Week Two we learned that Katy had a boyfriend in high school, a bassist named James, and that she went with James to Memphis and Nashville to get a start in the music business as a singer. We learn that Katy’s singing career never took off, and that James started dealing drugs and was on his way to tuning into a pimp, so Katy left him. We meet a name named Jack, who owns a junkyard in Pawtucket Katy parks her car near, once every few nights, and that Jake, although he doesn’t need the money, understands what Katy’s car might be worth as scarp.

In Week Three we learn how Katy picked herself off, dusted herself off, came home and took herself to nursing school, and a little about her life then, when lots of people she knew were coupling up for the night or even a few hours, but she kept her focus. We meet a woman named Tina who runs a hairdressing studio on Mineral Spring Avenue, and who sees Katy as she walks by, headed to the Pawtucket Library, and who thinks about Katy, just for a moment.

In Week Four, Katy remembers meeting her husband, Todd, who was in the Navy, having their son Rickie and moving to Quonset, then to North Kingstown Rhode Island. She walks past a mover named Jaime, who is unloading appliances at an appliance store in downtown Pawtucket, and who calls out to her to offer her a cup of coffee, but she doesn’t hear him. She remembers Todd’s disability and abuse as she walks. She remembered being a wife and mother and creating a safe world for her son as she reaches the library.

In Week Five, Katy sleeps in the Pawtucket Library for a few hours, and then leaves so as not to be thought a nuisance and begins walking to the Rochambeau Library in Providence. She remembers her affair with a doctor named Phil, and her heartbreak when it fell apart.

_

Meredith was the house on Blackstone Boulevard before she was the house on East Avenue, that grand old Queen Anne Victorian with a full acre of grounds, with a butterfly garden and a gazebo behind it. Her friends thought she was crazy to live in Pawtucket, of course, but crazy is as crazy does and what is life for if you can’t live it large. Meredith and Ev didn’t stay there very much, truth be told. Narragansett and Nantucket in the summer. Beachfront in Palm Beach in the winter. With a little time in St. Moritz or Vail. Country mouse and city mouse.

–

The house on East Avenue was a civics project, if you must know, civic beautification, for the general good. Too painful to let a grand old lady like that one fall into ruins. The painting alone was a major project: finding the right palate for the property, so the house could sit gracefully amongst those tall pines and hundred year old maples. It took real work to find colors that complemented one another and reflected the beauty of that spot, on a hill, set back from the road but visible, commanding but modest, colors that catch the light of the rising sun which falls on the house in the morning, and colors that amplify the beauty of the dusk and the ponderousness of the shade — so yellows and greens and browns, a splash of pink and purple. The house itself was a marvel, the complex layers of shingles and siding a study in contrasts, in possibilities.

The woman sat on her low stone wall, the wall that ran along the East Avenue side of the property and had slivers of sharp stone cemented into the top of the wall placed there on purpose, exactly to keep this from happening, to keep passersby from sitting on the wall. The woman herself was non-descript. A generic white woman with no particular defining feature, nothing that would let her stand out from the crowd. She was wearing a tired green down jacket and a brown hat. The down jacket was not in any way revealing or complimentary: it didn’t show her shape. She had gray hair that hung out of the hat on both sides of her head, flat, without body, in a manner that suggested she needed a shower. Meredith couldn’t imagine how she could be comfortable, sitting on that wall, but she also couldn’t imagine how a person let herself go out looking like that.

The police could be called. The police can always be called. Perhaps the woman was someone with mental health issues, so common now. People do hallucinate. She seemed old, for a heroin addict, but one never knows these days. Perhaps an ambulance. But the woman did not appear to be in any distress, and one hates to cause a scene. The world is full of people who have their own problems, their own lives, who walk about, cause no real trouble but never seem to get anywhere, to have any real impact.

So Meredith waited. When she looked out the window a second time, the woman was still there, and she thought again about the police. Then her phone rang.

When Meredith looked out the window again, perhaps twenty of thirty minutes later, the woman was gone, and Meredith never gave her another thought.

_

Ricky’s eyes. That was what hurt most. You don’t think about the unintended consequences when you are in it, when love and lust and passion get you in their grip, when a man’s or a woman’s voice, a lover’s voice, overtakes your own voice and your own reason. What happened next just happened, as if to someone else.

_

First Ricky moved out to stay with friends until he finished high school. Then he moved to Seattle, as far away as he could get. He shipped out instead of going to college, working on oil rigs and tramp steamers, following his father’s footsteps. The message was clear. I hate you now and everything about you. I hate your words and your stories and your love, so called. You shamed me and you shamed us and you lied to me all throughout my growing up. That’s what Ricky believed even though little of it was true. Doesn’t a woman deserve a little joy, even later in her life? Didn’t Katy deserve this one little thing for herself? Even if it was built on illusion? But Ricky had become a man like his father, and like a man who thought that the world, which turned only around him, had deserted him and then disappointed him, and he became an angry young man, as angry as he had once been loving as he had been as a child, now distant instead of sweet.

The pills were just one at a time, at first, medicines that patients refused. One became two. You can fudge an inventory. They weren’t as strict with pill counts in those days. I’ll put it back, she told herself. I’ll put it all back. Katy was working in a nursing home then, eleven to seven again, because she couldn’t stay at the Miriam after Phil. She couldn’t stand the way people looked at her, the way they turned their eyes behind her back.

Then she got caught. Then she lost her nursing license. Then Ricky overdosed on Fentanyl-laced crystal meth in Seattle and died. Then Todd died and Katy lost the house.

Katy stopped singing torch songs in her brain. Now she was singing the blues, when she was singing in her brain at all. Born Under a Bad Sign. Crying Time Again. And, I Wish I Was a Headlight on a Southbound Train. I Wish I Knew How It Feels to Be Free.

And Katy herself disappeared.

_

They were also nice to her in the Rochambeau Library. That branch is busier than Pawtucket, but the librarians there are also respectful and kind, just like the librarians in Pawtucket, only in a different way. More ethereal. Off in their own worlds, but respectful of Katy’s space and privacy just the same. They were also clearly there to help, not that Katy was looking for help or notice of any kind. Librarians are like that. They listen and they know and they are there to help, but they respect your space and privacy. Where would the rest of us be without them?

_

The reading room in Rochambeau is brighter than the one in Pawtucket. Lots of direct sun. There are more people going in and out. Katy picked up that day’s issue of The Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times and set them on her lap until her chest warmed in the light of the late afternoon, flowing through the windows. Then she took off her coat. And fell asleep. No one will bother a person who reads the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times. Regardless of how they are dressed or what they look like.

–

The walk back was long and slow. The sun was going down now. A cold wind came up, damp and chilling. The trunks of the trees lining the street were no protection. They were naked, like tombstones. They say a cold wind blows right through you but that isn’t so. A cold wind blows into you, into your back and your pelvis and your chest, sucking out all the fire inside, the way a child will suck out the last little bit of liquid when she is drinking a milkshake through a straw.

–

Katy shivered. It felt like her heart was slowing. She sat down on a chair someone had put out on the street as garbage. Then she stood again and walked. It doesn’t work, walking to stay warm. It doesn’t warm you. It’s another lie you tell yourself to keep going. One step at a time. One foot in front of the next.

People don’t see the sweep of the land now. They don’t feel the land with their feet. Most people just push a pedal and the space between places disappears.

But Katy felt every step.

She walked past the Miriam Hospital, and shivered a little to be back there, the wound from that place never having healed. Doctors wearing white coats, nurses in scrubs at the end of their shifts, and patients tottering behind walkers walked in and out. A part of her wanted to be recognized. A part of her knew she wouldn’t be.

She was old now. None of the sparkle that was in her eyes then. Phil had packed up and moved on to another job, a bigger job in Boston. He’s probably getting ready to retire, Katy thought. She imagined his retirement party and the speeches that would be made by colleagues and grateful patients. If only they knew the whole truth.

But none of that mattered now. No one in the hospital was looking outside to see what was happening around it. Everyone inside was flat out, just trying to survive the flood of people who were flowing into the place. Legends in their own minds.

She walked down the hill on Fifth Street, walked on North Main for a little while and then crossed the highway on Smithfield Avenue. Route 95 was full of cars, their headlights like the eyes of swarming insects. The wind whipped through her again. The cold wrapped itself around her face and neck.

You don’t see the people in cars as they drive on a highway after dark. You don’t see the people in cars in daylight either. Just bugs. Carapaces. Shells with headlights. Hard on the outside. Empty on the inside. An endless line of cars. Like a swarm of insects, moving through the darkness, tunneling into the night. That’s all people are, really, Katy thought. Swarms of bugs. Moving about. Going nowhere fast.

One foot in front of the other. One step at a time.

Smithfield Avenue, on the other side of the highway, is a lonely place. There were houses on the hill straight ahead, but Katy turned right, to go north. It might be North Providence over there, not Pawtucket. Some of the houses had porch lights on. Big TVs showed through the living room windows of other houses, the bright colors in constant motion, the people acting in the movies on those TVs the only signs of life in the universe right then. Houses are like cars that way. You don’t see the people inside. Just shells with lights on. Humps of wood and glass and black or grey roof shingles, with a chimney, antenna, or a little satellite dish on top. Nothing warm. Empty on the inside. Only boxes. Little boxes. All made out of ticky-tacky. All look just the same.

There was a florist on one side of the street. A graveyard and then schools on the other. Katy sat on a bench near one of the schools. And dozed for a few moments.

Standing up seemed impossible. But then she stood with what felt like superhuman effort. I just have to get up, she thought. Can’t stay here. Hypothermia and all that.

She imagined herself as a puppet, being pulled up by the hand of God, which was astounding because she didn’t believe in God. Only man. And woman. And the earth her feet walked on.

The schools seemed cruel because their grounds are endless. Maybe half a mile of walking. Maybe a mile. Probably only a few hundred feet. It didn’t matter. It felt like forever. Any distance is too much when you are so cold inside, when all the energy, all the life force, has been drained from you.

Then she passed a fire station as she turned the corner. Then the baseball diamond and the park on one side and little houses, little boxes, on the other.

Katy imagined the heat being on in those houses. She imagined sitting in a bright yellow kitchen listening to the radio as she made dinner, the oven on, the heat from the oven making the kitchen the warmest room in the house. She imagined that she was making meatloaf at first, and then she remembered that Ricky never liked meatloaf, so she imagined making pecan pie.

She’d start the car when she got back to it. Turn the heat on full blast. Sleep for a little bit. And then move it up to Lincoln, to those houses on the hill to the left as you go north, among those houses where the police don’t always come.

She noticed she couldn’t feel her feet anymore but that her legs kept moving, one foot in front of the next. She was cold all the way through. Her back was cold, the center of her chest was cold and she imagined that her heart was still, just barely beating, its ventricles fluttering as if they were wings and not a fist contracting and then releasing, a butterfly, not a pump. The car was there, right around the corner. She’d arrive, start the engine, and all would be good.

Katy turned the corner.

There was no car.

Impossible, she thought, I know I left it here.

She walked a block, stumbling, searching every inch, as though she were looking for keys or eyeglasses she had misplaced. Perhaps I am remembering wrong, Katy thought. Perhaps I left the damn car in Lincoln or in the Walmart parking lot. Maybe I am just old and confused. My mind isn’t what it used to be. The damn car is here. It has to be here.

But there was no car.

They towed it, she thought. They finally fucking towed it. Don’t they know? She wondered. Don’t they understand?

She turned and walked north toward Mineral Spring Avenue, putting one foot in front of the next. She sat down when she reached a bench in front of Lorraine Mills.

She was alone, but not lonely, then. There was no one around. She could sleep in peace. Nothing was wrong. Time straightens out all difficulties, and life is a gift. This moment is different than any before it. It’s now.

_

The temperature dropped to twenty degrees that night. People drove by the woman all night long. She was sitting bolt upright on the bench and seemed fine. You don’t want to interrupt anyone’s privacy. Better to mind your own business.

_

In the morning, school kids who came from across the street to meet the school bus saw her and saw she was blue.

The police were called.

___

Please click here to receive Michael Fine’s monthly short story and intermittent Covid-19 updates. Please invite others to join by sending them the link here. Information about Michael’s books, stories, posts, talks and performances is available at www.MichaelFineMD.com or by clicking. Join us!

___

Read Part One here: https://rinewstoday.com/the-sad-and-lonely-death-of-katydid-desrosiers-part-one-michael-fine/

Read Part Two here: https://rinewstoday.com/the-sad-and-lonely-death-of-katydid-desrosiers-part-two-michael-fine/

Read Part Three here: https://rinewstoday.com/the-sad-and-lonely-death-of-katydid-desrosiers-part-three-michael-fine/

Read Part Four here: https://rinewstoday.com/the-sad-and-lonely-death-of-katydid-desrosiers-part-four-michael-fine/

Read Part Five here: https://rinewstoday.com/short-story-the-sad-and-lonely-death-of-katydid-desrosiers-5-by-michael-fine/

This ends the story of The Sad and Lonely Death of Katydid Desrosiers by Michael Fine

___

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor in Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.

He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.

He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.

Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.