Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Outdoors in RI: Help keep recreation areas clean. Invasive Milfoil, trash. 2A update – Jeff Gross July 26, 2024

- Real Estate in RI: Highest-ever sale in Queen’s Grant, EG $1.25M, by Residential Properties July 26, 2024

- Homeless in RI: Gov. Newsom issues Executive Order. Remove California’s encampments. July 26, 2024

- Let the games begin. XXXIII Summer Olympics – John Cardullo July 26, 2024

- GriefSPEAK: What would you do? – Mari Dias Nardolillo July 26, 2024

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

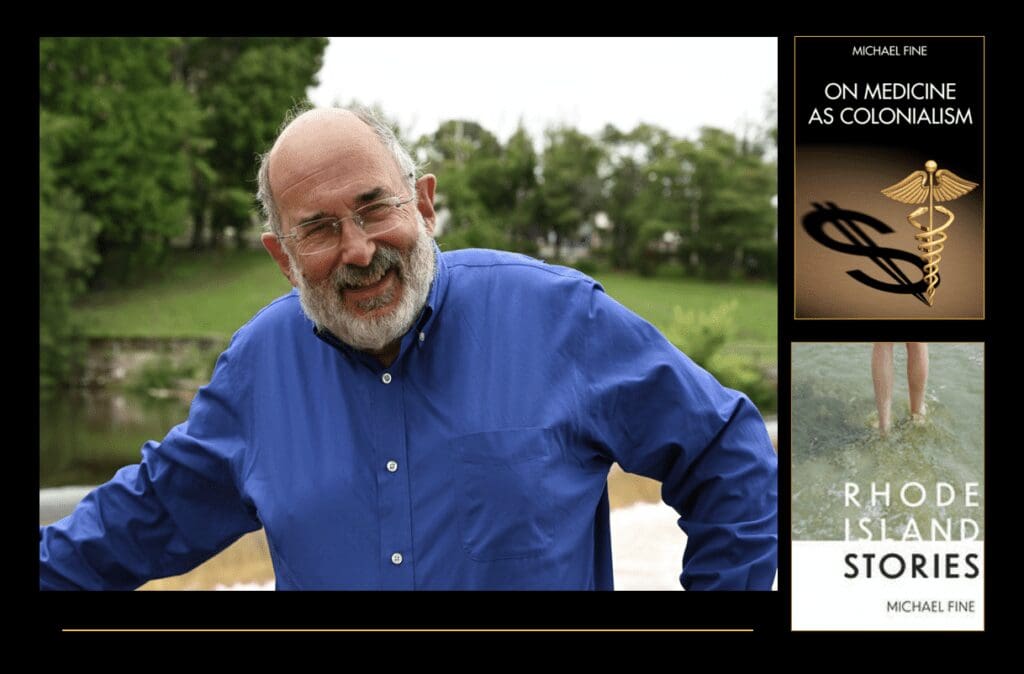

Short Story: The Sad and Lonely Death of Katydid Desrosiers (5) – Michael Fine

by Michael Fine, contributing writer

Week Five

Note to readers: This story is longer than most I’ve written, so we’re going to send out one section a week over the next six weeks – and we’ve included a brief summary of what’s been sent so far to catch you up in case you missed prior weeks. I’d suggest starting it on your cell, and if you like what you see, consider downloading it and printing it out — it’s a little long to read cramped over a tiny little screen. It’s available for printout on https://www.michaelfinemd.com/short-stories.

The influence of Leo Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Illich will be apparent to many readers, and is gratefully, and humbly, acknowledged.

Copyright © 2023 Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

In Week Two we learned that Katy had a boyfriend in high school, a bassist named James, and that she went with James to Memphis and Nashville to get a start in the music business as a singer. We learn that Katy’s singing career never took off, and that James started dealing drugs and was on his way to tuning into a pimp, so Katy left him. We meet a name named Jack, who owns a junkyard in Pawtucket Katy parks her car near, once every few nights, and that Jake, although he doesn’t need the money, understands what Katy’s car might be worth as scarp.

In Week Three we learn how Katy picked herself off, dusted herself off, came home and took herself to nursing school, and a little about her life then, when lots of people she knew were coupling up for the night or even a few hours, but she kept her focus. We meet a woman named Tina who runs a hairdressing studio on Mineral Spring Avenue, and who sees Katy as she walks by, headed to the Pawtucket Library, and who thinks about Katy, just for a moment.

In Week Four, Katy remembers meeting her husband, Todd, who was in the Navy, having their son Rickie and moving to Quonset, then to North Kingstown, Rhode Island. She walks past a mover named Jaime, who is unloading appliances at an appliance store in downtown Pawtucket, and who calls out to her to offer her a cup of coffee, but she doesn’t hear him. She remembers Todd’s disability and abuse as she walks. She remembered being a wife and mother and creating a safe world for her son as she reaches the library.

_

She found a reading chair off to the left, the one under the heating duct, took off her coat and fell asleep. And dreamt of the summer, of insects flitting in the warm sun. And then of a policeman, knocking on her window, telling her to move on.

She woke at two-thirty when middle schoolers began to fill the computer desks and library tables and got rowdy with one another, the days of absolute quiet in a library long gone. She became aware of two librarians who appeared to be coming in to check on her, taking turns. Perhaps she had been snoring. Perhaps she looked even more pale than she thought, and they were checking to see if she was still alive.

She was older now. Her fingers ached. Her back ached. Her ankles and knees hurt so much that it was often torture to walk, at least at first, and her balance was about gone, so she had to walk very slowly. Her energy and her breathing were weaker than they had been, perhaps, but she coped. Slow and steady. That was how she went. You can do anything, one little bit at a time. You can tolerate anything if you take it in tiny bits, one day, one hour or one moment at a time. There is nothing to fear but fear itself. This moment is different from any before it. The next moment with be different from this.

She woke with a start. Can’t overstay my welcome, Katy thought. So she stood up, put on her coat, and walked slowly outside again.

There are other libraries, she thought. Perhaps I can get as far as Hope Street. And then back to the car after dark.

_

It was a fool’s errand and Katy knew it right from the start. Phil was a married man. There was no future with him. He had cheated before and would cheat again. Cheaters never prosper. He wasn’t all that good looking, to tell the truth.

Phil was about five-nine but built like a tank. Fifty. A full head of graying dark hair that he wore swept back and rimless glasses, so he looked like a college professor, not an oncologist.

A doctor. Katy knew to stay away from doctors. She hated their arrogance, the way they assumed that the world turns around them. She remembered nursing school, when nurses wore little white hats and were expected to give up their seats when doctors came on the ward, as if their work was so much more important than nurses work, when the truth was the other way around.

No hesitation when Phil stepped into a room. No humility. Katy liked smart men, the kind of arrogant misogynic men who were pulled up short by her curiosity and fearlessness and found themselves liking it, despite themselves. The challenge of making fools of them excited her imagination.

But Phil was different. Several degrees more arrogant, of more self-satisfied ego. Quite the challenge. She knew he was trouble the moment he looked at her, let his eyes sweep over her and then fixated on her eyes without any apology, with the arrogance that said, I want that, without waiting for her to look back, without caring about how she responded to him, because he was so sure of himself that he knew how she’d respond. It troubled her that she responded exactly that way. But that didn’t stop what her heart did next. As much as she tried to suppress it.

–

The heart is an unpredictable beast ravaging through the underbrush. They had a patient together, a woman who was dying of her lung cancer, whose body was overwhelmed but who wouldn’t quit. We do terrible things to people at the end of their lives unless you stop us, Phil told the woman. We’ll stick a tube in your throat unless you stop us. We’ll stick needles in your arms, sometimes in your legs, sometimes in your groin. Sometimes we tie you down. Sometimes we sedate you with medicines that keep you from thinking. If your heart stops, we break all your ribs, trying to restart it, although restarting it almost never works. Most people want their families around them, to be as awake as possible, to get medicine for pain but not to be tied down.

He said these things with Katy in the room, not unkindly but with a little more detail than was called for, but the woman rebuffed him anyway, angry at him, at the world, at everyone. She wanted everything done. It was her life. No one could tell her how to end it. She had disowned her family. She was going to die alone. I’ll sue you all, she said, if you don’t give me everything I have coming to me, everything I deserve. She somehow didn’t understand or acknowledge that soon there would be no plaintiff, that she was going to die and her will, her wants, her personality, was about to evaporate.

“You have to live with your choices,” Phil said to the woman, pulling no punches and taking no prisoners. “I don’t. I just write the orders in your chart and then I go home. I’m not the one who is going to be stuck in a bed with a tube down my throat, with my arms tried down, full of needles and tubes.”

Phil was so damn sure of himself. And frank at the same time, and clear, which took courage. When Phil turned his attention to Katy, on the other hand, he was all present, as present as he had been with the dying woman, only moreso and in a different sort of way. Suddenly, as if transferring his energy from that woman to Katy, he seemed completely absorbed by Katy, and by wanting her. Call me when that woman dies, he said, and gave Katy his cellphone number. Fuck you, she said to herself. Don’t come on to me when a woman is dying.

The woman didn’t die on Katy’s shift. Instead, she got transferred to the Intensive Care Unit to be intubated, which was where she stayed for two more months, intubated and sedated, just consuming resources, just because she could.

Katy called Phil to tell him about the transfer, which wasn’t entirely necessary, but it was polite. She called from her cellphone, so now he had the number, and the rest, as they say, is history.

What a mess. One bad decision after the next. Meetings in parking lots. Drives to the beach, where Phil had a beach house but borrowed a friend’s beach house anyway, just to be safe, which meant so he didn’t have to worry about his wife walking in. Late night dinners in hidden little restaurants, back-alley places in Cranston and Warren, dark and romantic places despite their obscurity, Italian and Portuguese places with white tablecloths and rich food where Phil sat with his back to the door and to the window on the street so he wouldn’t be recognized. Late night phone calls. Intimate details about each other’s lives, about their marriages and families, and long stories about the things they’d done and loved doing that they couldn’t tell anyone else about.

People at work could tell. The other nurses and the ward secretaries all knew without being told, but Katy didn’t care. She was with this beautiful man. She was sitting in the catbird seat. She was having her cake and eating it, and the rest, well, they were just jealous.

It ended badly, of course. Really badly. Phil’s wife knocked on their door in North Kingstown late one fall afternoon just after the sun had set, when an insistent wind was blowing a cold rain. Ricky opened the door. The woman started screaming at him, loud enough to get Todd up from his easy chair in the den.

Things went downhill from there. Katy didn’t care one whit about what Todd thought or did. She could give as well as she got, and he was a broken-down old man by then. But Ricky never looked at her the same way again and that hurt worse than breaking it off with Phil, who she realized was just a stuffed shirt as soon as she took a moment to think about it, after the sting of being caught doing something wrong had faded, after Phil just turned tail and ran from her instead of standing up like the man he wasn’t and leaving his wife for her, which a part of her wanted and a part of her feared. No part of her ever really expected Phil to leave his wife for her, because she always knew who Phil was, even when she wasn’t admitting it to herself. And most of her knew that living with Phil and his insatiable raging ego would have been a disaster.

Down the hill. The sun was out for a moment, thank goodness. There was a cold wind but Katy’s core had warmed. The wind hadn’t found its way inside her coat yet. Down the hill and along East Avenue. Then up the hill again, a slow torturous walk, so she could cross the highway from the Hampton Inn and Murphy’s Law side to the Checks Cashed and the Mr. USA Cleaners side.

Katy hadn’t counted on the wind over the highway, which was fierce enough to stop her from time to time. The cold pierced her coat again. Her fingers and feet started to go numb. She started to shiver, just a little, and cursed her body for doing that to her.

A squat white woman and a thin Black man were standing across the street with signs, panhandling the cars as they stopped at the streetlight before they came barreling across George Street to get on the highway or turned left to head into Pawtucket. There but for fortune, Katy thought. But then realized she was no better off than they were. They looked a little strung out, she thought, but at least they have the energy to hustle, and at least they have each other.

Then she went left onto East Avenue, and walked down a little hill but then up the hill in front of the high school. A short low hill that felt long and tortuous. One foot in front of the next. One foot at a time.

___

Read Part One here: https://rinewstoday.com/the-sad-and-lonely-death-of-katydid-desrosiers-part-one-michael-fine/

Read Part Two here: https://rinewstoday.com/the-sad-and-lonely-death-of-katydid-desrosiers-part-two-michael-fine/

Read Part Three here: https://rinewstoday.com/the-sad-and-lonely-death-of-katydid-desrosiers-part-three-michael-fine/

Read Part Four here: https://rinewstoday.com/the-sad-and-lonely-death-of-katydid-desrosiers-part-four-michael-fine/

Part Six, and the final installment, appears next Sunday

___

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor in Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.

He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.

He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.

Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.