Search Posts

Recent Posts

- It is what it is – Jen Brien April 24, 2024

- Time for Sour Grapes – Tim Jones April 24, 2024

- Tenor and Pianist, Michael DiMucci: Songs From the Heart at Linden Place Mansion April 24, 2024

- World War II Veteran, Louis Dolce, turns 100 – TODAY April 24, 2024

- Rhode Island Weather for April 24, 2024 – John Donnelly April 24, 2024

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

The Sad and Lonely Death of Katydid Desrosiers – (part two) – Michael Fine

by Michael Fine, contributing writer

Week Two

Note to readers: This story is longer than most I’ve written, so we’re going to send out one section a week over the next six weeks – and we’ve included a brief summary of what’s been sent so far to catch you up in case you missed prior weeks. I’d suggest starting it on your cell, and if you like what you see, consider downloading it and printing it out — it’s a little long to read cramped over a tiny little screen. It’s available for printout on https://www.michaelfinemd.com/short-stories.

The influence of Leo Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Illich will be apparent to many readers, and is gratefully, and humbly, acknowledged.

Copyright © 2023 Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

In Week One, we met Katy Desrosiers, a woman who is living in her car, an old green Saturn with one white door, and learn a little about how she lives. She moves the car from place to place and parks it at night where she isn’t likely to be noticed. She spends her days walking, to libraries and to parks to stay warm, but also so she won’t be noticed. We also meet Vernon Jenkins, who lives in Lincoln, in one of the places Katy parks her car some nights. We learn that Katy was born in Rutherford, New Jersey, just over the Hudson River from New York City, and was a singer. Then we meet a woman who is a television anchor and was a newspaper reporter, who notices Katy’s car, and remembers she one had a car like Katy’s.

–

Katy and James went together to Memphis, which seemed like the place to go if you were a singer, or that was what James said. Memphis, Nashville, or Detroit. Back before hip-hop. We’ll get you a gig singing backup and me playing sessions and we can build it from there, James said. Just wait until them people hear you sing.

You don’t know a person until you know a person. You don’t know yourself, don’t have any idea that you can be twisted and bent like a sapling or a trumpet vine, turned around and into something and someone you don’t know and never met, just because you feel something for someone and want to please them, the way you hope and believe that they want to please you. Even when they don’t.

The sad truth was that James wasn’t who he appeared to be. Or there were parts to him that Katy didn’t see and could never have imagined. He appeared to be confident and connected. He appeared to be completely into Katy, a man who found her in a little band and saw something in her that she didn’t see in herself. She thought she was a plain white girl who could sing a little. James acted like he thought she walked on the moon. Or that was what he said. When I dream, I dream of you. He appeared to be a man who would twist himself into knots for her, who would sacrifice himself and his future, just to be with her, as if only she mattered.

Maybe some of it was true, at least at the beginning. But it didn’t last. There wasn’t any back-up work for a white girl singer in Memphis. Most people knew that. There were white girl backup singers for rock bands in LA, girls who could sing with a little blue-eyed soul, but Katy and James had moved to Memphis, not LA, and Katy had a voice that was too big for most backup. Too big for back-up but a voice that needed its own songs. But Katy was a singer, not a songwriter.

So they tried Nashville for a little while. It was only four hours away. They found out quick that white girl singers were a-dollar-a-dozen there, and they all had big voices, they all could sing, and they all had loser boyfriends like James who were using them to try to be what those men could never be themselves. That it wasn’t who you were but who you knew. And what you would do for them today. Katy wasn’t country. If anything she was jazz. A torch singer. They were nowhere near New York or Chicago or New Orleans. Katy didn’t know jazz people anyway, and they didn’t know her.

As Katy would learn later, what happened next was so common it was almost trite. Of course their money ran out. Of course James took to dealing. He had been dealing at home, small-time, only to friends, mostly musicians, so he knew the ropes. This time he had bigger dreams. Of course he went out to see a guy and Katy stayed in the cheap motel, trying to write country songs, but all she could see in her mind was the New York City skyline, the one she could see out the window of her school and of her house, and the way the buildings across the river glinted in the sunlight beneath red and purple clouds as the sun set behind her to the west. She could see the Christmas tree over the skating rink at Rockefeller Center, and the humps of yellow cabs on Fifth Avenue, darting from here to there in the rain. Nothing about trucks, truck stops, pickup trucks, trains, or prison. Nothing about some other woman stealing your man, who was better off gone, truth be told.

Of course James traded around for what he had to sell. With whomever. For whatever. Of course, of course, of course. Katy twisted herself around, trying to make it right, trying to make it normal and natural and healthy and good. Until James tried to trade her.

And then something inside her let go and she snapped back like a rubber band. This isn’t me, that something inside her said. This isn’t real. James is a small-time drug dealer, not a bass player. And I’m not singing torch songs on a well-lit stage, standing in a glittering dress.

–

His grandfather had come with nothing and turned nothing into an empire. Junk. What other people threw away.

His grandfather could barely read or write when he came here. He wasn’t aristocracy. His people weren’t rabbis or scholars or even the managers of estates. They weren’t even grain merchants or shopkeepers. His great-grandfather was a simple cowherd and woodcutter who died of tuberculosis when his grandfather was ten, leaving his grandfather in a hovel at the edge of a tiny village in Galicia, a hovel with a dirt floor and a straw roof that was always leaking, where they stuffed old cloths and newspapers into the cracks between the boards to keep the wind from blowing through the house in the winter. Poor children didn’t wear shoes in the summer. In the winter they bound their feet in rags or wore wooden soled shoes when they could get them. They wore hand-me-down clothes that didn’t fit. They existed on charity and a garden. Jake’s great-grandmother made soup from potatoes and onions, and sometimes they drank the milk from one cow that Jake’s grandfather would lead each morning to the commons in the center of the village and lead back and put in the cowshed at night, a cowshed that was just a lean-to off their tiny hovel. All under one roof.

They were almost too poor to be Jews: Jake’s grandfather didn’t go to the school in the next larger town when he was three or seven like most Jews. He didn’t go to live with an aunt or a grandparent because there were too many mouths to feed. He didn’t go to school. He spent most of his childhood hungry and cold until he ran away when he was twelve. And then he was still hungry and cold but no longer trapped and abandoned. Where was he going? He didn’t know. Who would he live with? He didn’t know that either. All he knew was that he had to get out.

Jake’s grandfather walked. And he begged. He slept in wheatfields and in barns. He traded work—digging postholes, cutting and loading hay, picking apples and cherries – for food, as he made his way west. Even he, ignoramus that he was, dirt poor and uneducated, without friends or family, had heard about this place, this America. He didn’t know anything about streets paved with gold. All he knew was that it was different, and different and far had to be better than hungry and cold all the time. He made his way to Gdansk, what the German’s called Danzig. And stowed away in a boat thinking he was going to America, a boat that put him off in Liverpool. In Liverpool he did what he always did. He hustled.

That was where Jake’s grandfather learned a little about rags and bones and the rag trade. That was where he learned to survive on junk, to make something what other people throw away, like a cockroach in the cervices, a cockroach that survives, a species that existed millions of years before humanity and will outlast us. That was where he learned the golden rule, that he who has the gold makes the rules, where he got a little cash and used it to bribe his way onto another boat and stowaway again. First to Montreal, and then, one night in the summer, across the border, walking and sleeping in the fields. First to Albany. Then, because he could hitch a ride with a trucker, to Providence. In 1912. Jake’s grandfather was fourteen when he came to Rhode Island.

He spoke Yiddish, Ukrainian, a little Polish, a little Russian and a little German. He taught himself English and a little Italian, so soon he could speak to anyone and everyone in Providence and Pawtucket, Rhode Island, where he became the king of junk, of rags and bones. Junk turned into scrap metal which turned into recycled materials, and into paper recycling, plastics recycling, auto recycling and that all turned into real estate, with a little division for software and hardware engineering because one of Jake’s cousins was good at tech, and now there was an art gallery in Newport, for another cousin, because all of them, it seemed, had inherited Jake’s grandfather’s gift for making something out of nothing, for understanding that one person’s trash is another person’s treasure, for understanding as well that there is a sucker born every minute, and that time and tides wait for no man or woman either.

Jake had done pretty well for himself, building on what he got from his parents and grandparents. He was like his grandfather. He was not an intellectual. They sent him to Moses Brown and then he went to URI. And finished, more or less, with a degree in engineering.

Jake thought with his hands. He could see upside where many other people couldn’t, and he knew how to cut his losses, how not to throw good money after bad when a deal turned sour, as some do. Just the cost of doing business. No harm done, nothing ventured, nothing gained but you just got to know when to cash out or shut something down. You don’t let a partner take advantage of you. Never. They have to believe you will take their house if they mess with you. Take their house or mess up their kids or worse.

He kept his office in the yard in Pawtucket, in what some people called a junkyard, and he liked nothing better than to put on work clothes and heavy gloves on a cold day in the fall or winter, and spend an afternoon working with the guys, unloading the trucks full of scrap as they came in, breaking rusted machines apart or running the compactor. He liked to get his hands dirty. It made him feel real.

The house with the barn and fancy horse, that was his too, and he knew how to run even the horses for upside, but somehow, that house and barn was not quite so real. His grandfather would have looked over his glasses at Jake when he saw that, and muttered to himself in Yiddish or in Ukrainian, but then he would have tussled Jake’s hair and smiled to himself, because what Jake’s grandfather loved most was that that he himself had survived, and he loved that he had survived when he thought of all those high and mighty people, the teachers and the rabbis and the shopkeepers and the grain merchants and the little factory owners who didn’t. Let the boy have a horse, his grandfather would have said. What’s the problem? His grandfather never let his doubts or fears slow him down, but he never forgot who he was or where he came from, and Jake didn’t either.

The car had one white door. Parked on the road leading to their place. Nobody ever parked there at night. Maybe someone had left it there for the morning, hoping to push it in and get a few bucks for it on its way to the crusher. They weren’t worth much, those Saturns. They ran and ran. But once they gave out, they had no resale value at all, other than for scrap.

___

Read Part One here: https://rinewstoday.com/the-sad-and-lonely-death-of-katydid-desrosiers-part-one-michael-fine/

Part Three appears next Sunday

___

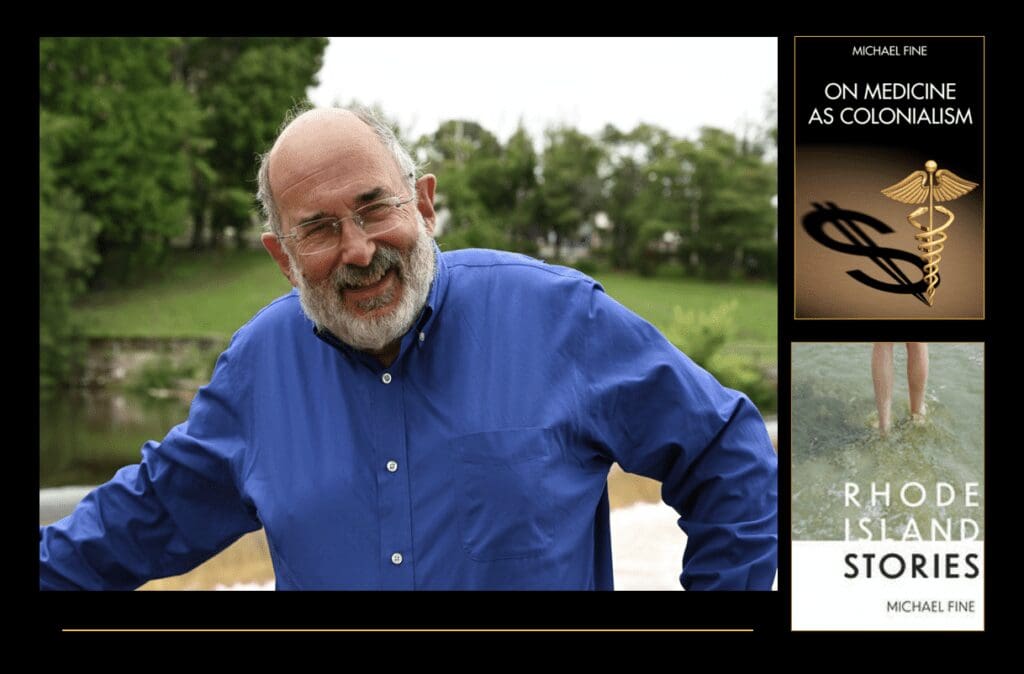

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor in Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.

He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.

He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.

Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.

Thank you for such a well-written, moving story. Definitely worth considering a book.