Search Posts

Recent Posts

- ART! Gallery Night: Providence art tours. Walk or ride. Guided or go on your own. April 16, 2024

- Top 5 hacks to kick-start your vegetable garden – Mary Hunt April 16, 2024

- RI nonprofits share in Point32Health Foundation grants for equity in aging, social and racial justice April 16, 2024

- Business Beat: BankNewport promotes Evan Rose April 16, 2024

- Tradição! Portugal’s passionate about it’s symbol April 16, 2024

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

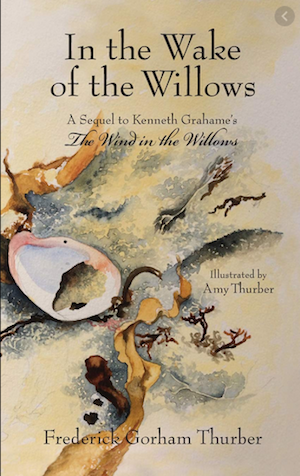

In the Wake of the Willows…by David Brussat

Photo: Salt marshes along the Westport River, in Massachusetts. (Lauren Daley/Herald-News)

by David Brussat, Architecture Here and There

Nightly over several recent weeks – interrupted by a bout of Bell’s palsy – I read to my 11-year-old boy (and his mother) an enchanting children’s book called In the Wake of the Willows, by Frederick Gorham Thurber and lovingly illustrated by his wife, Amy. The author, a Providence native, distant relation to the comic writer James Thurber, and a naturalist living in Westport, Mass., wrote the book in homage to Kenneth Grahame’s 1908 classic, The Wind in the Willows – which he first read years ago and I read to Billy and Victoria just before In the Wake, which we finished last Friday.

It was stated in a review of In the Wake by freelancer Lauren Daley for the Herald-News of Fall River, Mass., that its prose was “in an old-fashioned vernacular.” That brings to mind that my former editor at the Providence Journal, Philip Terzian, was often said to “affect a British accent.” Not so. Terzian spoke in full sentences of correct grammar; it only sounded like a British accent to those unused to full sentences or correct grammar. Likewise the prose of Fred Thurber: It is beautiful and energetic, like some if not all literature of the past, but that hardly makes it “old-fashioned.”

I opened the book to this passage at random as an example of Thurber’s delightful prose and narrative power:

A whip-poor-will started up in the far distance, singing its endless, monotonous song; Mr. Rat knew that this would go on all night, minute after minute, hour after hour. Why the repetition?, thought Rat. He did a quick calculation in his head, and the total was rather surprising. You would think that the lady whip-poor-wills would get the message after the first few minutes and say yea or nay; what good would it do to keep going? Maybe the whip-poor-will figured if romance did not come on the first song, maybe the ten thousandth would win her heart. …

The fact that this passage does not ring of Dickens or Thackaray does not condemn its hearty, our-side-of-the-pond modernity. It is not modernist, it is modern, with the clarity and pace of its time. Just because it is about animals does not require it to be cutesy.

My family was well-prepared to measure Thurber’s storytelling prowess against that of Kenneth Grahame, and, given Thurber’s ancestry we were not altogether astonished to find that in his prose, in his story, and in his ability to infuse animals with a human sense and sensibility, the old shoe fit very well on the modern writer. In fact, although I am not familiar with the English habitat of the original Toad, Mole, Badger, Otter and Rat (whose families seem to have emigrated to the Westport area), Thurber, who has spent decades charting Westport’s natural charms, appears to have vaulted past his literary predecessor as a naturalist of flora, fauna, landscape and waterscape. Reviewer Daley writes that Thurber told her:

Every place in the book is based on real locations in our area: The River, of course, is the Westport River. The Beach is Horseneck Beach. The Point is Westport Point. The Inn is the Paquachuck Inn. … Montaup Hill is the Native American name for Mt. Hope in Narragansett Bay. Hen & Chickens Reef is the Hen & Chickens Reef off Westport. The Island really exists, but I dare not aggravate my animal friends any more by disclosing its exact location … suffice it to say, it’s within sailing distance of Westport.

Is it really a children’s book? Probably not more so than The Wind in the Willows. As in the passage above, Thurber deftly manages to suggest in the book that the author is an observer and even a friend, if not an intimate, of the riverside community, who are real animals in a real society, as was the animal society across the pond. Thurber accomplishes the task of blending human character and characteristics into his animal characters. The beasts seem less mammalian in their behavior than, say, Winnie the Pooh. I would hesitate to insist that Thurber tackles such literary challenges with as much vivacity as Grahame. That might strike Thurber as a species of sacrilege.

So, like Wind in the Willows, In the Wake of the Willows is, it seems to me, an adult children’s book. Thurber describes its target audience as ranging from age 12 to 112. He warned me to read the afterword before reading it to Billy. I did, and had no worries. I don’t often get to brag on my child in print, but Billy was not fazed at all by the events of the afterword. I will add, too, that Billy was captivated by the “souls of the innocent” in an early (and spiritual) chapter, and kept joking about them as the story rolled on without seeming (at least in Billy’s mind) to resolve their fate. I came to enjoy his reaction to my plopping the phrase in, willy-nilly, at various points in the book.

So, yes, this is a children’s book that is fun for adults to read, especially to children. In fact, I found Fred Thurber’s prose easier to read than that of Kenneth Graham, whatever that might signify. Maybe the august British author was just pretending to write for children, or just pretending to write about animals. I think Thurber’s In the Wake is the real McCoy.

To read the complete article: https://architecturehereandthere.com/2020/05/17/in-the-wake-of-the-willows/

My freelance writing and editing on architecture and others addresses issues of design and culture locally and globally. I am a member of the board of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which bestowed an Arthur Ross Award on me in 2002. I work from Providence, R.I., where I live with my wife Victoria, my son Billy and our cat Gato. If you would like to employ my writing and editing to improve your work, please email me at my consultancy, [email protected], or call (401) 351-0457 https://architecturehereandthere.com/