Search Posts

Recent Posts

- RI Veterans: Did you know? 25.04.24 (100th for Louis Dolce, events, resources) – John A. Cianci April 25, 2024

- Business Beat: Bad Mouth Bikes takes home 3 national awards April 25, 2024

- Rhode Island Weather for April 25, 2024 – John Donnelly April 25, 2024

- We Cook! Mill’s Tavern’s Cajun North Atlantic Swordfish, Mango Salsa, Cilantro Citrus Aioli April 25, 2024

- The Light Foundation & RI DEM’s 4th Annual Mentored Youth Turkey Hunt a success April 25, 2024

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Guatemala’s peaceful Cayala – David Brussat

by David Brussat, Architecture Here and There, contributing writer

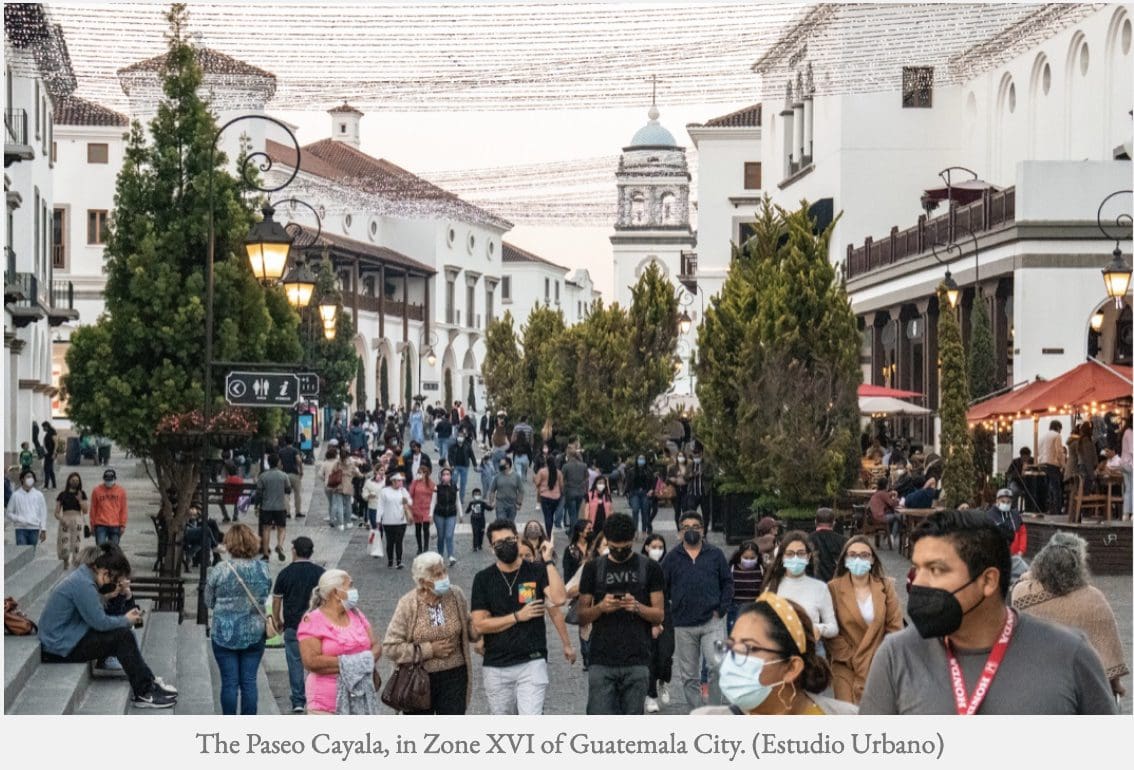

Photo: The Paseo Cayala, in Zone XVI of Guatemala City. (Estudio Urbano)

Cayalá is a new town on the edge of crime-ridden Guatemala City that has grown stronger since it was planted in 2011. I’ve written about its lovely mixture of Spanish and Mayan design influences, starting as early as 2012 in one of my weekly columns for the Providence Journal. In a 2015 post on my blog I made what is now a common error in descriptions of Ciudad Cayalá – the city of Cayalá – I called it “allegedly ‘gated’.” In a comment, architect Steve Mouzon corrected me: Cayalá is not gated, neither the town as a whole nor its central business district, known as the Paseo Cayalá. Since then, however, journalists on the left have made a cottage industry of false narratives regarding Cayalá.

Fortunately, those narratives are generally ignored by the residents of Cayalá, its many visitors and admirers from around Guatemala and the world, plus its famously droll master planner, Léon Krier, and his two lieutenants, architects Pedro Godoy and Maria Sánchez, founders of Estudio Urbano. Still, the false narratives do sting, and do hurt Guatemala more broadly in its efforts to stabilize and improve its damaged society.

The goal of reforming architecture globally and returning beauty to its rightful centrality, in Guatemala and in the United States, requires, also, that such narratives be exposed and seen for what they are.

Before continuing on this theme, allow me to quote my own first description of Cayalá from that 2012 column, called “A new classical flower in Guatemala” and posted on my blog in 2015 following news of a visit to Guatemala by Providence Mayor Jorge Elorza:

Ciudad Cayalá is a new town being built on open land beyond the city center but within the city’s broad boundary. Developed by the landowner, Grupo Cayalá, and masterplanned by Léon Krier, who spearheaded Prince Charles’s new town of Poundbury (outside Dorchester, England), Cayalá’s Phase I was finished in November. It incorporates Mayan ornamental detail amid a robust Spanish classicism. Streets and squares are lined with colonnades. A monumental set of steps ascends to the Athenaeum, designed by Notre Dame Prof. Richard Economakis, forming a pyramid of Mayan descent, topped by a Spanish temple. Photos hint at the glory of ancient Rome, whose classical buildings mounted to an urban epiphany with a seemingly natural, unplanned grandeur.

The gates theme seems to have begun with an article by Scranton University associate professor Michael E. Allison for what is now his blog called Central American Politics, focusing on the transition of (supposedly) former Central American rebel groups to political parties. In 2013, the UK Guardian posted an Associated Press story (“Guatemalan capital’s wealthy offered haven in gated city“). In 2017, Adventures Guatemala ran an article based on Allison’s reporting (“Private city built to escape crime“). Last year, in the journal Kairos, Rutgers University published “My visit to an invented city of privilege,” by a professor Madhu Murali. It is filled with one of the silliest collections of “outraged” leftist platitudes I’ve ever read. Most articles on Cayalá that are not advertisements for residential units there seem to be obsessed with its nonexistent gates, its security, and the idea that its beauty somehow makes the town inauthentic.

Memes that pop up in writing by Allison and picked up by other writers include not only the alleged gates but the impact of Cayalá on efforts to restore the old center of Guatemala City – the Centro Histórico, as distinguished from the far older former capital, Antigua Guatemala (now a UNESCO world heritage site), which is located some 25 miles from the capital.

Detractors [of Cayalá] say it is a blow to hopes of saving the real traditional heart of Guatemala City by drawing the wealthy from the urban center to participate in the economic and social life of a city struggling with poverty and high levels of crime and violence.

But there is another meme associated with that concern, one which has today become ubiquitous in the United States as well, with equally dire consequences for Guatemala:

One consideration why some people want to live in Cayalá boils down to the fact that many of the wealthy are simply racist. They do not like their fellow citizens. In fact, they don’t even think of them as citizens.

People who want to protect their families and themselves from crime are not racists for preferring safety to danger. To turn such an allegation into a dominant narrative, at least among the elite, risks destroying a society’s mechanisms to improve the lives of citizens. In all societies, self-preservation has been the concern of all humans. In free societies, citizens have the right to plan for the betterment of their families, in part by selecting residences that are safe, schools that provide quality education, and jobs that offer prospects for higher income. Societies such as Guatemala, young democracies that are rising from periods of civil strife, have these same natural rights as free peoples, and it should be the purpose of government to honor and to protect those rights.

In Guatemala, it is not the alleged racism of the wealthy who move to Cayalá that poses a threat to social reconciliation or the restoration of the Centro Histórico. It is the violence itself, and the racist narrative that can promote distrust and even justify violence – Guatemala’s long civil war ended recently, in 1996. Violence is what sends those who can afford it to safer places, in or out of Guatemala, at all levels of its society (as we have seen, for example, at the U.S. border).

Arising from its history and, more recently, the Cold War, violence and injustice by Guatemalans against Guatemalans have brutalized life. Whether most of the guilt lies with the former rebels, the military, Guatemala’s elites, or U.S. support for the government, Guatemalans and their civil institutions, local and national, must work for a better future. A narrative that equates citizens’ desire for safety with racism, if it takes hold in social discourse, can only undermine the nation’s hopes for such a future.

Cayalá and the safety it offers do not work against restoring the Centro Histórico, let alone efforts to reach a modus vivendi in Guatemala; rather it is a safety valve that slows flight from the country and permits civil reconciliation to continue within its borders. It is a model for peace. When Guatemalans of all levels see an alternative to civil strife, progress will surely follow – if the people want it to, if it is allowed to happen. Cayalá thus serves a positive good in society as a lubricant for the gears of social advancement in Guatemala.

Wealthy Guatemalans who have moved from the old town to the new town are not prevented from contributing to that social advancement, whether by helping to finance the Centro Histórico’s restoration or by participating in the broader social, financial or political efforts to bring comity. Anyone at any level of income can visit Cayalá to shop, dine, visit friends or partake of its beauty. Its charms can only raise incentives to better pacify and beautify the rest of Guatemala, and serve as a model for one way of doing so. False narratives only retard prospects for a better future for all – a truth that spans not just that nation but the world.

[At the end of this post are several photographs of Paseo Cayalá and Ciudad Cayalá. The first, from the UK Guardian, gives a sense of the distance from the central business district of Guatemala City. The rest, from Studio Urbano, taken from ground level and from above. Finally, there is a photo of Antigua Guatemala from the Expat Exchange.]

[Correction: The original version of this post mistook the old historical center of Guatemala City for the Antigua Guatemala, a former capital some 25 miles from today’s capital. That error was fixed by 11:54 p.m. Friday.]

***

This month, Cayalá won a Charter Award from the Congress of the New Urbanism. Celebrating the award is an article, “The Cayalá effect in Guatemala City,” from the CNU Public Square journal by its editor, Robert Steuteville. Its opening line seems to contain the “gated community” meme: “The Paseo Cayalá Neighborhood in Guatemala City is a model of open and economically resilient development in a city of gated development.” It turns out that by “city” this means Guatemala City, not Cayalá.

To read the complete article go to: https://architecturehereandthere.com/2021/05/21/guatemalas-peaceful-cayala/

_____

My freelance writing and editing on architecture and others addresses issues of design and culture locally and globally. I am a member of the board of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which bestowed an Arthur Ross Award on me in 2002. I work from Providence, R.I., where I live with my wife Victoria, my son Billy and our cat Gato. If you would like to employ my writing and editing to improve your work, please email me at my consultancy, [email protected], or call (401) 351-0457 https://architecturehereandthere.com/