Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Johnston secures federal funds for all 9 home buyouts on Belfield Drive with persistent flooding April 23, 2024

- ART! Celebrating 13 years of Art Connection RI – at Shri Yoga April 23, 2024

- Rhode Island Weather for April 23, 2024 – John Donnelly April 23, 2024

- New Budlong Pool: Cranston DPW sets public meeting on ways to recognize its history April 23, 2024

- May 1st RI State House event launches Mental Health Month programs. Awards, personal stories. April 22, 2024

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

The twisted historicity of the William Blackstone statue – David Brussat

by David Brussat, Architecture Here and There, contributing writer

William Blackstone, or Blaxton (1595-1675), has long struck me as the mildest of colonists, perhaps not even a colonist strictly speaking. He was a recluse, and when other colonists showed up, he exited stage left.

An ordained priest of the Church of England, he landed with emigrants in (what became) Weymouth in 1623, from which he migrated in 1625 to (what became) Boston in 1630, becoming its first settler and first resident of Beacon Hill. After inviting Puritan settlers from (what became) Charlestown to share his land in Boston, he became disenchanted with his Anglican colleagues, after which he retreated (not fled as did Roger Williams) in 1635, settling in (what became) Cumberland across from (what became) Pawtucket, in (what became) Rhode Island.

Blackstone lived there peacefully – or so history seems to record – until his death in 1675, about a month before King Philips’ War. Aside from breeding the first American strain of apples, building his home, “Study Hill,” which at the time housed the colonies’ largest library, preaching to natives who would listen, and traveling on a bull while reading (not illegal at the time) to visit his friend Williams not far away in (what was already) Providence, he seems to have done very little of interest to historians, so far as I can tell. He may have been the least belligerent man on Earth.

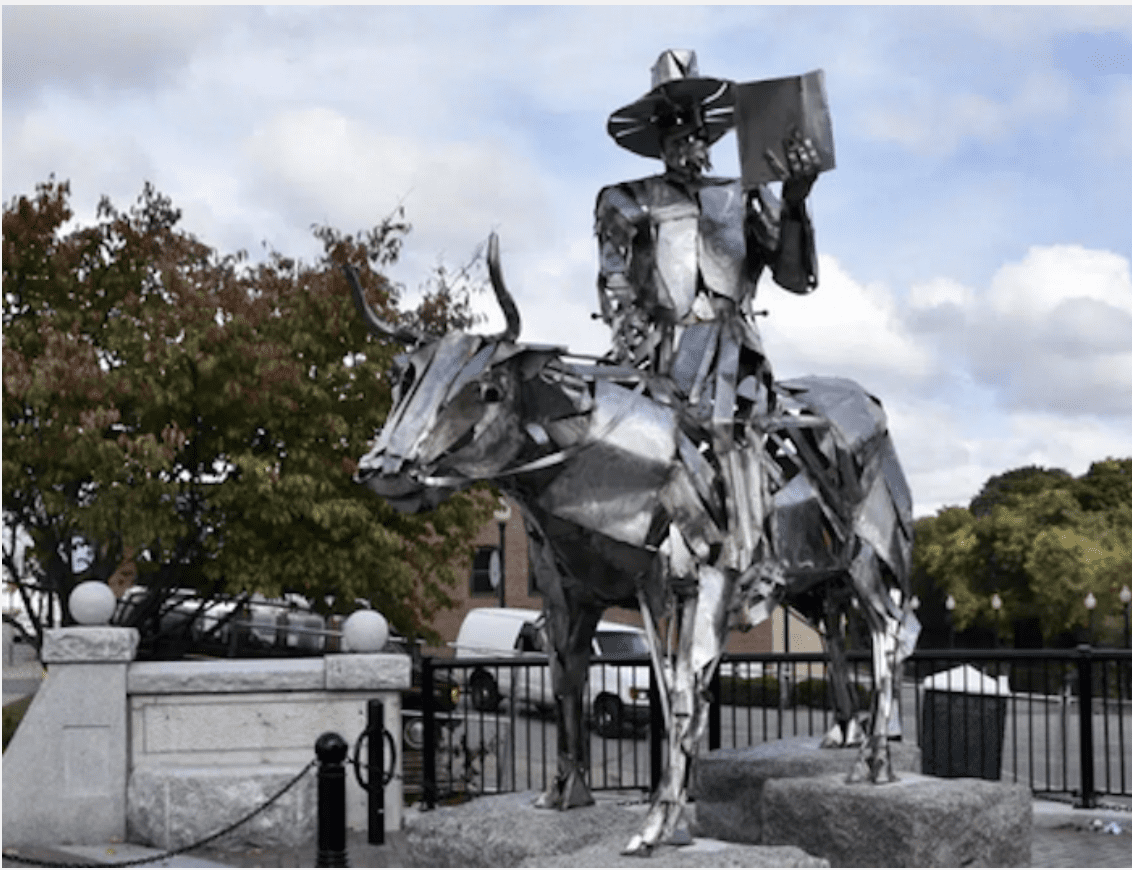

A town in Massachusetts, a river, a canal, Providence’s ritziest neighborhood and its grandest boulevard take Blackstone’s name, but now a statue of the bookish hermit – no relation to the famous British jurist, Sir William Blackstone – is raising a stink next to the river that bears his name in Pawtucket.

Native Americans today, at least some of them around here, are irked that Blackstone’s fame as the first settler in Boston and Rhode Island flies in the face of the fact that several Indian tribes predated him in each place he settled. And at some point a tribesman (or woman) of this or that tribe would have become the first settler in each of those places, long before Blackstone, so his “firsts” are of a twisted historicity invented by the white man’s culture.

This Columbus Day (Indigenous Peoples Day to some), a gathering of about a hundred people, largely representatives of the Narragansett tribe but including various African-American activists and others, gathered to protest the recently erected statue sculpted of sheet metal shards by Peruvian native and Providence resident Peruko Ccopacatty. A story in Uprise RI by the activist Steve Alquist quotes Pawtucket City Council member Melissa DaRose:

“This monument only goes to show that it seems like we [the black, brown and indigenous community] don’t count,” said Council member DaRosa. “We’re not included. We were not included in that communication. The Blackstone Travel Council did not reach out to the Narragansett Indian Council.”

Narragansett tribal elder Bella Noka added:

“If I were to be raped, and see my rapist on a statue, and you tell me, ‘It’s okay. Yeah he did some bad things but we’re going to discuss those things. We’re going to find out exactly what was good about him and what was bad about him, but we’re going to keep [the statue] there.’ That’s what you’re doing,” said Bella Noka. “Shame on you if you’re supporting that man.

More to the point was the statement by Narragansett tribal elder Randy Noka, who said of the statue, “For those who see something in it, more power to you. I think it is an ugly piece of steel and should be taken down.”

He is correct that it is ugly, but not that it should be taken down. Ccopacatty’s style of sculpture leaves much to be desired, but it is a reasonably well crafted example of its type, which is legion in the world of art. The private and federal funds used to build out its space alongside the river is nicely traditional, and an admirable bit of urbanism, which Pawtucket cannot afford to spurn. Its quality, or lack thereof, should not form the basis for its removal.

In all the speechifying, nothing negative was cited about Blackstone except that he was a white settler who represented the oppressor civilization that since came to New England from far away. Four hundred years later, past injustice seems to have colonized the minds of many, oppressed and unoppressed, who now deny the progress made and seem intent upon demonizing the values of civilization that have made that progress possible.

The Declaration of Independence, a civil war fought to rectify historic wrongs, a civil-rights movement to surmount resistance to that rectification, and trillions in programs to transform that rectification into social and economic progress for victimized communities: Even as this valiant progress is denied, personal values such as hard work, diligence, humility and study that enable individuals to benefit from it are disparaged.

As they say, those who forget the past may be condemned to repeat it.

So maybe, far from removing the statue of William Blackstone, he should remain in place to be celebrated as precisely the sort of colonist the colonies could have used more of, especially the Narragansetts whose descendants gathered the other day in Pawtucket to pay homage (of sorts) to the new statue.

_____

To read RINewsToday story on “Tolerance”, the William Blackstone statue, go to: https://rinewstoday.com/art-peruko-ccopacatty-toleration-recognizes-pawtuckets-blackstone/

_____

To read Brussat’s complete article, go to: https://architecturehereandthere.com/2021/11/09/william-blackstones-statue/

_____

To read more articles by David Brussat for RINewsToday, go to: https://rinewstoday.com/david-brussat-contributing-writer/

_____

My freelance writing and editing on architecture and others addresses issues of design and culture locally and globally. I am a member of the board of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which bestowed an Arthur Ross Award on me in 2002. I work from Providence, R.I., where I live with my wife Victoria, my son Billy and our cat Gato. If you would like to employ my writing and editing to improve your work, please email me at my consultancy, [email protected], or call (401) 351-0457