Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Rhode Island Weather for May 22, 2025 – Jack Donnelly May 22, 2025

- We Cook! Mill’s Tavern Louisiana style beer braised Short Rib, Grits, Baked Beans, Cornbread May 22, 2025

- RI Veterans: Did you know? 22.05.25 (Medical, Memorial Day, War Dog, events) – John A. Cianci May 22, 2025

- RI Trucking Association calling on Governor and General Assembly to halt truck tolls May 22, 2025

- 8th annual Rhode Island Slow Pitch Softball Hall of Fame: Class of 2025 May 22, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

The Sad and Lonely Death of Katydid Desrosiers – (part three) – Michael Fine

by Michael Fine, contributing writer

Week Three

Note to readers: This story is longer than most I’ve written, so we’re going to send out one section a week over the next six weeks – and we’ve included a brief summary of what’s been sent so far to catch you up in case you missed prior weeks. I’d suggest starting it on your cell, and if you like what you see, consider downloading it and printing it out — it’s a little long to read cramped over a tiny little screen. It’s available for printout on https://www.michaelfinemd.com/short-stories.

The influence of Leo Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Illich will be apparent to many readers, and is gratefully, and humbly, acknowledged.

Copyright © 2023 Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

In Week One, we met Katy Desrosiers, a woman who is living in her car, an old green Saturn with one white door, and learn a little about how she lives. She moves the car from place to place and parks it at night where she isn’t likely to be noticed. She spends her days walking, to libraries and to parks to stay warm, but also so she won’t be noticed. We also meet Vernon Jenkins, who lives in Lincoln, in one of the places Katy parks her car some nights. We learn that Katy was born in Rutherford, New Jersey, just over the Hudson River from New York City, and was a singer. Then we meet a woman who is a television anchor and was a newspaper reporter, who notices Katy’s car, and remembers she one had a car like Katy’s.

In Week Two, we learned that Katy had a boyfriend in high school, a bassist named James, and that she went with James to Memphis and Nashville to get a start in the music business as a singer. We learn that Katy’s singing career never took off, and that James started dealing drugs and was on his way to tuning into a pimp, so Katy left him. We meet a name named Jack, who owns a junkyard in Pawtucket Katy parks her car near, once every few nights, and that Jake, although he doesn’t need the money, understands what Katy’s car might be worth as scrap.

You never know what you are made of until you find out by making a choice and acting on it. There wasn’t one moment or one event that got Katy going. She just woke up one day in Nashville, saw James for who he was, saw herself for who she was, and knew this wasn’t the choice she had made, this had all just happened by itself.

. Then she walked out. Took a bus home.

.

. You don’t just “go” to New York from Nashville. You put your money down – it was $40 then, which seemed like a lot – and then you sit in a hot smoky smelly bus that stops in half the little towns in Tennessee and Virginia, places nobody ever heard of, places surely God forgot, and you see and sit with all kinds of people, with all kinds of lives and all kinds of thoughts, urges, behaviors, desires, hopes and perhaps, even dreams. Tired people. Old people. Young people. Black and Mexican people. People who travel by bus move about the country as if the bus was the night, as if when you go by bus, nobody sees you.

. It was different then. People had no expectation of being treated decent. People only hoped they could slip in and slip out of places and stay invisible, because invisible was safer than the other choices, all things considered. Cookeville, Tennessee. Crossville, Tennessee. Knoxville, Bulls Gap, Greenville, and Bristol, Tennessee. Wytheville, Virginia. Roanoke, Lynchburg and Charlottesville, Virginia. Then you wait in Richmond for three hours for the bus to Washington, Baltimore, Wilmington, Philadelphia, Newark and New York.

. You see a different country in those places, different from the nation of yellow cabs, neon signs, fast food restaurants, and strip malls. You see a county of people for whom life isn’t easy, people who live with the complexities of what they’ve got, layered over by urges and choices made mostly in darkness. You smell their sweat and the diesel exhaust that comes from buses and trucks, and you hear the rumble and belch of tractor trailers as they thunder up and down the interstates.

.

The library was about a mile away from where she spent the night, parked on that hidden and abandoned back street near the junkyard in Pawtucket. The sun was out again after three days of cold rain. The sun was low in the sky: it was winter. Very cold nights, when nothing moved, were coming.

. One foot in front of the next.

. The hill after Lorraine Mills was tough. It made her stop after every block, a little short of breath, and walk slowly, but that’s how you go forward, one step at a time, one foot in front of the next. She listened to the music inside her as she walked, those old torch songs she loved: Summertime, This is a Fine Romance, and It Ain’t Necessarily So. She heard Ella Fitzgerald and Louie Armstrong, singing with pride and confidence, as if they lived a life of elegance on Fifth Avenue instead of just performing for people who did. She walked past the gas station on the corner of Lonsdale Avenue, and the McDonald’s across the street.

.

. She’d built her own life. Made her own choices. Her own mistakes, perhaps, but there were no mistakes. Just opportunities to learn something new about the world.

. Katy got home. She got herself into community college. She got herself a job as a nurse’s aide in the fancy nursing home in Allendale. Then she got herself a car and an apartment in Hackensack. And got herself into nursing school – classes during the day, then eleven to seven at night. You can study, sometimes, when the old people are asleep. And sometimes you can sleep yourself, your head on a table or leaning back in a chair in the break room, even though you are not supposed to. You are not supposed to, but everyone does. The good thing about eleven to seven is that the old people do sleep, most of them, or at least stay in their beds until morning, except for a few who wander. But aides and nurses take turns listening out and nobody gets hurt, most of the time. The people who fall and break a hip, well, that happens, but you can’t really prevent it. They fall getting in and out of bed, and they don’t call you before they do that, so they will fall whether the nurses and CNAs are awake or not. Sometimes they die in bed, in the middle of the night, but there’s nothing you can do to prevent that either. Everybody dies of something. You close their eyes when you find them and call the doctor to sign the death certificate, call the admin on call, and call the next of kin. All pretty routine.

.

. It was the eighties, and people were wild in the streets. They didn’t call it hooking up then, but that’s what is was: the joyous celebration of life, the delight in sensation, revealing what was hidden, discovering the other and other bodies, how they worked and what they wanted and what you could do with what you have. An explosion.

. Everybody’s libido was on overdrive. The pill wasn’t that new but people were learning how to use it. HIV was still a gay men’s disease and you didn’t think much about that then because people weren’t dying in droves from it yet.

. Not much of that happened in the nursing home on eleven to seven, but as soon as Katy got her degree, before she even got a license, she got a gig as a graduate nurse at Hackensack Hospital, and over there, everything was happening. Residents with nurses and aides in the storerooms, back when nurses wore prim little uniforms and just a few residents were women. Residents with residents. Nurses with respiratory techs and x-ray techs. Nurses with chaplains, with priests and rabbis. You name it. There was one male nurse with long blond hair and a tricked-out van he parked in the nurses’ parking lot away from the street light, and every night when the three to eleven shift was over he’d be there with somebody new, that van just bouncing up and down and shaking side to side because, though it had a slick paint job, the suspension of that van wasn’t any good — and there was lots of intense up-and-down and back-and-forth, and oohing and ahhing going on inside.

. Katy kept herself away from that craziness. She had been to that mountain with James. And learned that men were dangerous to her, that she could fall in love at the drop of a hat with almost anybody, with a baseball bat or a flat tire. Falling in love for Katy meant she gave herself away, she became different, a person she didn’t recognize, didn’t trust and didn’t know. Too dangerous. It was the straight and narrow for her now. Just work and school and then just work. There was plenty of time to discover the world later.

.

You got to hustle if you want to make out. Mineral Spring Avenue in Pawtucket ain’t Fifth Avenue New York. It ain’t no shopping mall. If you want the ladies to come in, you got to do more than just hang up some sign and pay some rent. Too much rent. You got to have chairs. You got to have stylists. You got to make sure them ladies show up to work, drama or no drama, the hell with what is going on in their lives at the moment, children, boyfriends, mamas, sisters and husbands, in about that order. You got to work it on social media, posting shit every day, so it looks like your little shop on Mineral Spring Avenue is the thing, some combination of home and women talking around a kitchen table, and a club with them lights and that music on a Saturday night. Music. Thumping music. But not too loud, you know, so the ladies can hear each other, because you don’t never want some woman to say she was surprised by what she got and she don’t like it. Like hair don’t grow back. Them ladies got no idea what they actually look like, so when they get some glimpse of themselves they weren’t expecting, they quick to blame their hairdresser. They forget that we are here to cover up what they actually look like, to create a distraction, a mirage.

. Then there are the communities to manage, the Cape Verdeans, the Liberians, the Nigerians, the Spanish and everybody else. Everybody wants to feel like this is their shop, that the people in the shop are there just for them. So you got languages to manage and services: you got to know what women want and make sure you match the ladies behind the chairs to the ladies who come through the door. And get the money right. And get everybody paid on time. Pay the electric, pay the gas, pay the phone bill and the landlord.

.

. Tina saw that old woman out of the corner of her eye, that eye that never misses a trick, She saw that woman through the shop window, tottering along on the street. First thing she thinks, ‘chairs are full, one of my ladies is late so I’m going to step in. We got no time for one more. She going to have to wait.’ Next thing Tina thinks is, ‘that baby looking mighty sketchy, mighty weak. Barely putting one foot in front of the other. Is that old lady okay?’ Next thing she thinks is, ’keep your eye out. Don’t want no old lady fallin’ out on my sidewalk, in front of my shop, on my property. There’s insurance. But people cast blame and sue your ass at the drop of a hat.’

. That woman kept walking though. She was running on empty, but she kept walking. That last girl came in through the back door, all flustered about this and that, all full of excuses.

.

Past the cemetery and that little park where Mineral Spring connects to Main Street. It seemed like the road would never end.

. Katy’s feet were tired and aching. Her fingers were numb from the cold. She felt a little chill in her chest.

. She walked to the left. That way she wouldn’t go down a hill that she’d have to climb again to get to the library. She imagined what these this place must have looked like before the mills and people, the roads and stores arrived. Low hills giving way to a river. A river gurgling, the water rushing to the sea. Shore birds and sea birds, following the river north. Huge trees and open meadows. Deer grazing.

. All that was so long gone that no one ever thought of it. Even the mills, which had blackened the skies and turned the river a disgusting shade of yellow-green had gone silent. Shells for many years. Many burned to the ground. Now lofts. The river ran clean again.

. She listened to music in her brain. Keeps your mind clear.

. She thought about what she’d heard on the radio to keep her mind off her feet and hands. The Donald was making lots of his usual noise but didn’t seem to matter as much now after all his people lost in the election. The pandemic was there and not there: people still seemed afraid of one another, never sure whether to touch or hug, to shake hands or to bump fists. The Russians were still invading Ukraine or trying to. They had been pushed back by the Ukrainians, who looked like the people we always wanted to be: wily, courageous, never giving up, and focused on freedom. So now the Russians were just bombing indiscriminately, the radio said, bombing schools and hospitals and knocking out power stations, as punishment, thinking they would make the Ukrainians cower. But that only made the Ukrainians stronger. Save Ukraini! I can survive the cold, Katy thought. They will too. Surviving makes you stronger.

_____

Read Part One here: https://rinewstoday.com/the-sad-and-lonely-death-of-katydid-desrosiers-part-one-michael-fine/

Read Part Two here: https://rinewstoday.com/the-sad-and-lonely-death-of-katydid-desrosiers-part-two-michael-fine/

Part Four appears next Sunday

___

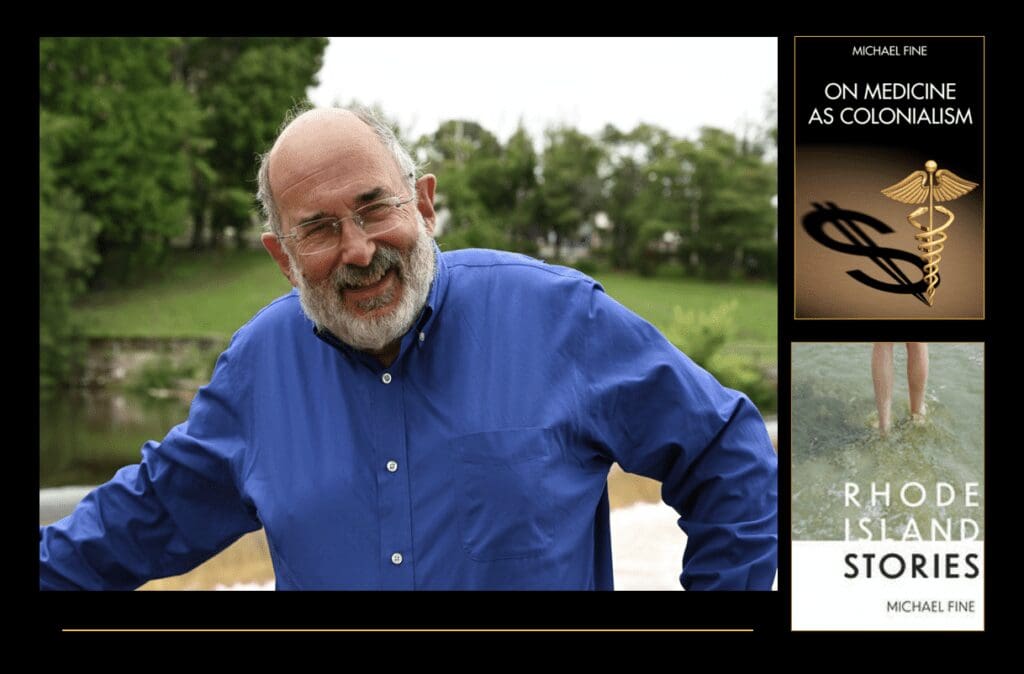

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor in Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.

He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.

He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.

Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.