Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Detailing Manhattan: Christopher Gray’s Legacy – David Brussat April 26, 2024

- Business Beat: BankNewport supports Kids’ Zone at new Save The Bay Hamilton Family Aquarium April 26, 2024

- Rhode Island Weather for April 26, 2024 – John Donnelly April 26, 2024

- GriefSPEAK: Dread. Fear. Welcome relief. – Mari Nardolillo Dias April 26, 2024

- Outdoors in RI: big animals, tiny Ticks, huge Trout, Chepachet’s Harmony Railway, 2A – Jeff Gross April 26, 2024

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Talking to someone who won’t get vaccinated starts by listening…

1/3 of unvaccinated adults say that the new FDA approval of the vaccines has addressed their safety concerns somewhat and they will now get vaccinated. This information comes from a survey done by the deBeaumont Foundation, which specializes in public health and the need to make broad changes in how we seek to impact populations with health information.

As school begins and the Delta variant rages on, being more contagious, vaccinations are more important than ever. Adults’ comfort vaccinating children over 12, too, will be important in combatting the virus and its spread.

All of us have friends, relatives and co-workers who remain unvaccinated. The reasons vary. The degree of passion on their decision also varies. Some who are more passionate than ever will not be swayed by anything they read or hear, or by anyone talking to them. They aren’t going to change their minds.

For others, they may not be as steadfast in their decision as we think and are open to hearing more information – but from the right source. One that is respected and acceptable to them. In that case, listening to what the concerns are is very important. They may be religious, or have a bad experience in the past, or culturally concerned.

We do know that having a conversation to better understand is important. Respect of one another’s decisions is important. Medical professionals, religious professionals, family members can all be effective communicators. To that end we share some tips and guidance on having those conversations, effectively. Yelling and losing one’s temper surely isn’t going to accomplish anything.

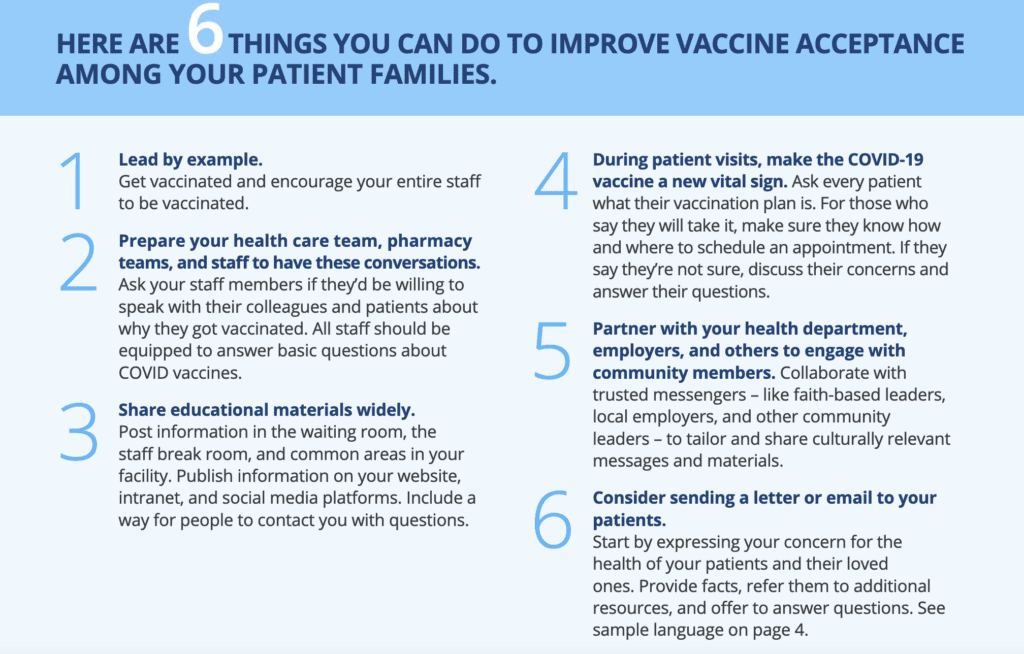

What physicians and medical professionals can do:

Ending the COVID-19 pandemic requires us to vaccinate as many Americans as possible. The new vaccines offer our best path toward saving lives, opening schools and businesses, and rebuilding our economy. The decision to get vaccinated is a personal one that is influenced by many factors. Research shows that Americans most trust their own doctor for information about COVID-19 and vaccines. People want unbiased facts about the safety and effectiveness of the vaccines – and information about whether vaccination is the right choice for them – from their doctor.

The nation is making good progress in getting more people vaccinated, but many still say they will probably not get

the vaccine. While numerous national and local efforts are attempting to address people’s concerns, the single most influential factor will be a strong recommendation from a medical professional.

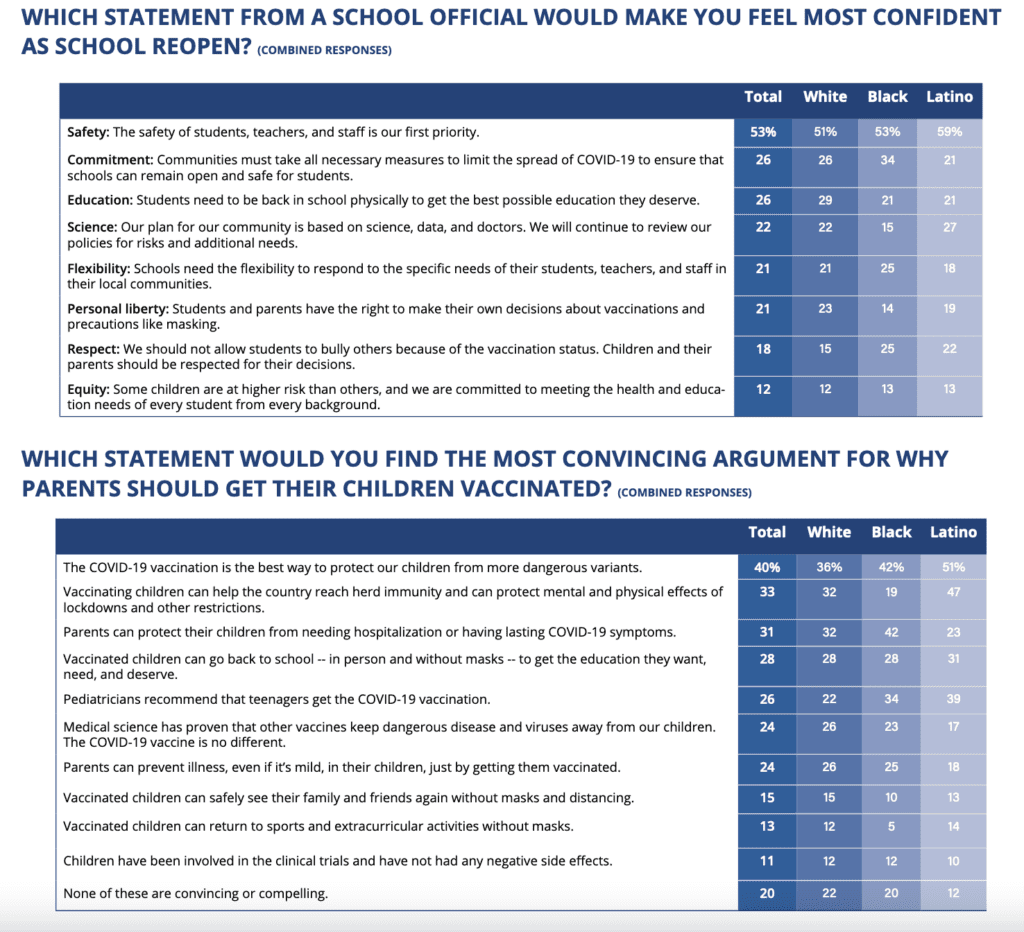

Talking to parents of school children: School officials are some of the most effective communicators. Teachers, staff, coaches, and athletic and school nurse leaders. The deBeaumont Foundation released these message points and target audience data.

Religious leaders

If it is a religious concern, think of asking your local priest or minister if they have a statement or a presentation they could make. Here is Pope Francis’ taped message to Roman Catholic followers:

Frank Luntz, a pollster and commentator, talks about vaccine hesitancy and how to talk with people to help them come to the decision. The interesting thing is Don Lemon’s facial expressions and disdain for some of the unvaccinated concerns raised by Luntz is demonstrating the opposite of how you should approach a discussion. But Luntz’s advice is helpful and makes a good listen.

Psychologists are studying the best methods – behavior change is a science

For those who prefer a more cerebral approach, some of the science is in on understanding vaccine hesitancy, the roots of beliefs, and what messaging and method of messaging may be helpful. In a study published by the American Psychological Association (https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/releases/hea-hea0000586.pdf):

According to the attitude roots model, one way to create change is to identify underlying motives for rejecting the science on immunization, and then to tailor interventions that are congenial to those underlying motivations (the so-called jiu jitsu approach; Hornsey &Fielding, 2017). From this perspective, the goal of science communication is to align with people’s underlying fears, ideologies and identities, thus reducing people’s motivation to reject the science. If the motivation to reject the science is reduced, then people should become more willing to embrace the evidence on its merits.

The current data identified three underlying attitude roots that are meaningfully implicated in antivaccination attitudes: conspiratorial beliefs, reactance, and disgust/fear toward blood and needles (the fourth predictor—individualistic/hierarchical worldviews—explained only a small amount of variance and so will not be discussed further). The particularly strong role of conspiratorial beliefs helps contextualize why corrective information and myth-busting about vaccinations has tended to be either ineffective or counterproductive.

For most people, official health messages asserting a scientific consensus about vaccination are reassuring and imply an underlying reality (the “consensus implies correctness” heuristic). But for those who have a conspiratorial worldview, these same ingredients—official pronouncements that imply a lack of dissent or that the “science is in”—can be inverted to be proof of a conspiracy.

From a jiu jitsu approach it is counterproductive to try to reduce people’s conspiratorial thinking (and there is no evidence that this is feasible). Rather, one should work with people’s underlying worldviews: to acknowledge the possibility of conspiracies, but to show how vested interests can conspire to obscure the benefits of vaccination and to exaggerate the dangers.

Similar methods might be possible for the other two predictors. It might not be feasible to reduce people’s levels of reactance. But it might be possible to align vaccination messages with that individual difference factor, by implying that antivaccination movements are high-pressure, highly conformist organizations in which individual freedoms are discouraged. For those who have high disgust toward needles and blood, avoidance of vaccination is a short-term anxiety reduction strategy. But interventions may be able to disable that strategy by reminding people of the consequences of disease in terms of hospitalization, illness symptoms, and exposure to surgery, blood and needles.

The choice is still theirs – and yours

Another tip if you are on a mission to help your friend or colleague come to a comfortable decision to be vaccinated is to talk to someone who was hesitant and got the vaccine – how did they feel? – what made them change their mind?

Some examples we’ve heard about are people changing their mind when they realize the choice is still theirs; or they are doing it for someone they love (their parents or children); or they want to fly and go to Disney and other locations without constant testing, etc. Others are getting vaccinated as part of a mandate at work, such as healthcare workers, and even a financial incentive such as direct payment, lottery tickets or being entered into a drawing such as the program in Massachusetts.

Finally, if a changed mind is not to be, then you’ve done what you can. You may not be the right messenger. You may be one of several messages the person will hear and it might take that awhile to sink in. So don’t think your words or your effort is in vain.

Also remember that you are in control of the risk you put your life and your health in. It might be a “no” to going out to eat with them; or taking a trip with that special friend. It may mean they don’t get invited to Christmas, or a wedding. The social cost may become more important to them than an unproven medical concern.

Also remember that there are some people who truly can’t be vaccinated – who are still staying in their homes, and being extraordinarily careful. And for those we have compassion and hope science provides relief soon so they can resume their lives.