Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Outdoors in RI: Help keep recreation areas clean. Invasive Milfoil, trash. 2A update – Jeff Gross July 26, 2024

- Real Estate in RI: Highest-ever sale in Queen’s Grant, EG $1.25M, by Residential Properties July 26, 2024

- Homeless in RI: Gov. Newsom issues Executive Order. Remove California’s encampments. July 26, 2024

- Let the games begin. XXXIII Summer Olympics – John Cardullo July 26, 2024

- GriefSPEAK: What would you do? – Mari Dias Nardolillo July 26, 2024

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Socialism is on the Rise – a short story by Michael Fine

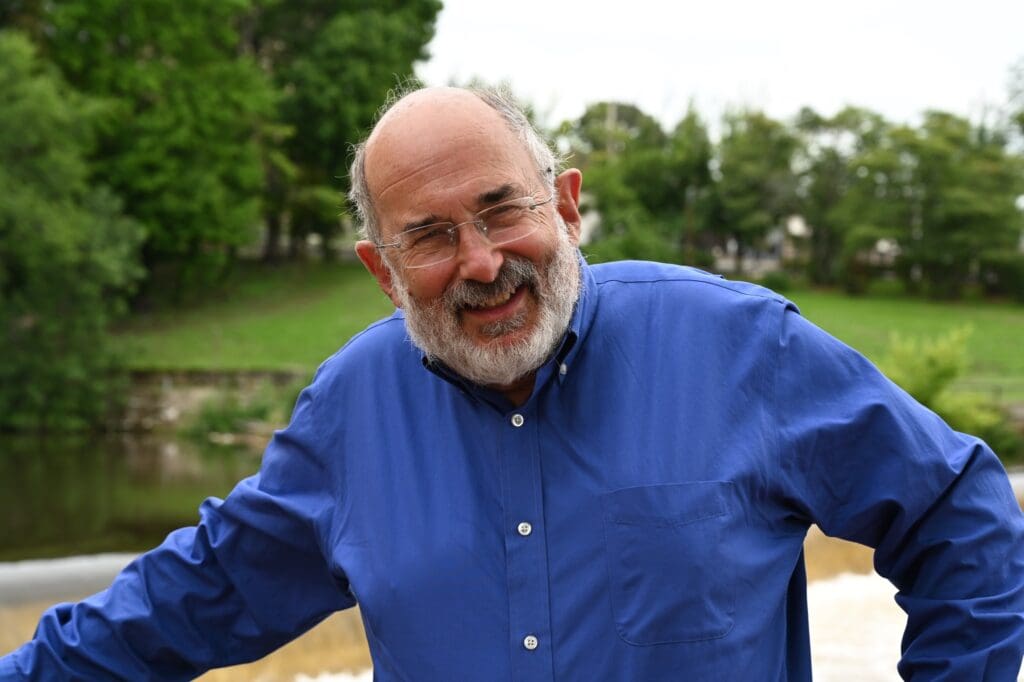

By Michael Fine

Copyright © 2022 Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

__

Some readers may want to skip the last few pages, which comprise something like an essay about the various economic and political systems people refer to when they are insulting one another on social media or running for political office (and using this terminology imprecisely), terminology the story that follows is intended to critique.

Socialism on the Rise is dedicated to Larry P Arnn, President of Hillsdale College.

__

When they got the call, Vernon and Louise were already fed up. 18 hours into a 24-hour shift. Twelve runs so far, most of them garbage, people calling 911 for a headache at three am, for back pain so bad that the dude walked down into the street to meet them and climbed into the bus himself. A 3-year-old kid with a fever. Which all kids get. Don’t people have any sense anymore? Vernon wondered. You take Tylenol for fever. Or headaches. If you have to take anything. Everybody gets back pain once in a while. Nobody dies of it. Almost nobody.

There was one very old very polite English-speaking Cape Verdean guy with congestive heart failure, sweating and short of beath. Ninety-six years old, God bless him. Little barrel-chested guy, brown as a nut, all shriveled up except for his ankles which were as big as balloons but bright-eyed and bushy-tailed despite it all. Smart as a whip. A little O2, an IV and some IV Lasix. He turned around before they had him wrapped and packaged and loaded in the van. O2 saturation went to 97 percent, thank you very much. From 46 percent. An anaerobe. That was a righteous transport. But only one out of a hundred.

But the rest? Mostly crap, mostly people who didn’t speak English, didn’t have anything like an emergency, and just wanted to get out of their own houses because they were anxious or bored or wanted to build a good story so they could hit up the ER guys for some Percocet.

This new call was a bridge too far. Go to the State House. And sit and wait. There was a demonstration. The state cops were talking about clearing out the homeless people camped out in the rain in tents on the esplanade. Talking about clearing them out. Not clearing them out yet. They were serving coffee and donuts to these people. And pizza. They had three or four people from the Governor’s office going from tent to tent, pushing out some line about relocating them to a better place, but Vernon knew and everyone else knew there wasn’t any better place, there was a homeless shelter where they have bunk beds and where those people get put out back on the street every day at 6 am to go hang out at Kennedy Plaza or panhandle in front of traffic lights on Memorial Boulevard. Who did the politicians think they were fooling? There was a crowd of noisy demonstrators as well, to cheer on the homeless people, not the cops. The brass wanted an ambulance on standby in case somebody fell down. What is the world coming to? Vernon wondered.

These people in tents, they are just like all the rest, Vernon thought. They sponge. They don’t want to live by anyone else’s rules. They don’t want a job. They all think the world owes them a living. Owes them a house. They think they are all victims.

And the demonstrators are more of the same. Do-gooders. Brown and RISD students from California or New Jersey. Dressed scruffy but from money. Talking about the working class, about this kind of justice and that kind of justice and how angry they are. On and on about how homeless people suffer, as if those demonstrators had just woken up from a long sleep and discovered that it sucks to be poor. So, they are shocked. Shocked. It sucks to be poor. It sucks worse to be homeless. Don’t do it. Which is why some of us work every single day. So, we don’t have to live like that. It also usually sucks to be crazy, although some people are so crazy, they don’t even know that it sucks. Any questions? All this from people who just didn’t know how good they have it.

Louise didn’t give a damn. She was happy just to sit there, sit on her cellphone and text, and let the Capitol police and the state cops do all the heavy lifting.

Not that there was anything to do but stand around, drink coffee, watch the circus, and try to stay warm and dry. There is no bad weather, the saying goes, only inadequate clothing. And Vern was pretty well suited up.

Vernon, he couldn’t sit still, like always. He went out in the driving rain to see what was going on.

It was December. It was raining and cool but not too cold yet, thank God. The rain made the marble blocks of the esplanade glisten. The wet marble reflected the State House lights and the emergency lights of the police cars which lit up the dark morning. Better rain than snow, Vernon thought. An inch of rain equals ten inches of snow. If the air was ten degrees colder, they’d all be standing in slushy mess, the homeless people would be more miserable yet and the demonstrators would be home in their nice warm houses. But bellyaching anyway.

The tents were green, blue, and orange, but looked drained of color because of the rain and the dark sky. They were pitched on the marble block floor of the esplanade, which was cold and hard and could not ever be a comfortable place to sleep or even sit. Put a tent on the ground and the earth is at least a little spongy. Lay on a bed of leaves and you might even get comfortable, sleeping in the woods. But here? The wind whipped across the esplanade, cold and unforgiving. People walked by all day long, as cars, trucks, and busses ran up and down Smith Street, just a few feet away, rumbling and gaseous, so the air smelled of diesel and car exhaust, with a hint of the rotting seashore smell that comes up from the harbor, flowing into the low place between Smith Hill and College Hill, which used to be a cove, or so Vernon remembered reading, a cove that had a waterfall, and an old lover’s meeting place, amazing but true, given that it was all paved over and covered with roads, traffic, and buildings now. You could see the lights on College Hill. The sun must rise over College Hill, Vernon thought, and must set off to the west, over the hills of Johnston, Scituate, and Foster, over a horizon punctured by cathedrals and high-rise elderly housing.

Socialism, Vernon thought. Everybody wants something for nothing. Nobody wants to work. Nobody wants to think. Everybody thinks the world owes them a living.

There were wheelchairs parked among those tents. Wheelchairs and bicycles. How do these people live, Vernon wondered. Why do they bother?

–

Then Louise comes out of the truck, which wasn’t like her. She goes to talk to one of the organizers, a short, stocky, dark complected guy with a goatee. He takes her over to one of the tents, one of the tents with a wheelchair in front of it. And she squats down.

Now Louise isn’t a thin woman, and she doesn’t ever hustle. She’s a good enough partner, if you’re like Vernon and you like someone who doesn’t talk and if you don’t talk at all yourself. She hangs back on runs and lets Vern be first on scene. Let’s him do all the talking, which is fine with Vernon, because he’s an antsy guy who always wants to be first on scene, size things up, treat or run and be done, the EMT version of treat and street. Save who can be saved, move anything that needs to be moved mucho pronto, so they don’t crash and burn in front of your eyes — and then get the hell out of there. And tell the bellyachers and the drunks and the insurance frauds that they don’t need the hospital and that they are full of it but yes, we will transport because that’s the law. Vern is the guy who gets written up a couple of times a month for mouthing off. Not Louise. She hangs back, doesn’t talk, doesn’t complain but sometimes pats people on the shoulder after she’s put the 02 on when she thinks Vern isn’t looking. If and when she does anything at all.

Louise crawls into that tent. It’s a blue-green tent but it looks almost grey because of the rain and the dark sky. Funny how these people have state of the art tents from REI and so forth, tents Vern was sure cost four hundred bucks if they cost a cent, all made of space age materials with rain flys and fancy doors and mosquito netting and so forth. It just doesn’t all add up.

Vern can only imagine what that tent must look like and smell like inside. Face it, these people don’t bathe. There ain’t no place for them to bathe. There aren’t any bathrooms either, other than the ones in the State House, and Vern can’t quite imagine the Capitol Police letting people like this into the statehouse after five. Or into the State House at all. Piles of clothes, mostly wet inside, he figures. Body smells. Old food wrappers. Mildewed orange rinds. Used Dunkin Donuts bags. How do they cook? Do they have little camping stoves, or do they just eat any food that comes their way cold? Mildew, he reckons. It’s got to smell like the inside of old gym sneakers that sat in a gym locker for months. What kind of light do they have in there, anyway? Some old flashlights with the battery running down? Better to think there isn’t any light. That way Vern doesn’t have to think about what he doesn’t want to see.

–

Fifteen minutes later, Louise crawls out of the tent and stands up. The rain had let up a little, but it was still spitting and miserable. A wind makes the tents and the flags in and around the statehouse snap, flap and shake, the flags looking a little sad, sagging because they’re wet. The rain smells damp and tired, like the rubber from old tires.

Someone wearing a watch-cap and a big purple parka crawls out of the tent. Louise helps that person pull themself up and swing into a wheelchair. The person in the wheelchair starts motivating towards Vern’s rescue. Louise follows right behind, though she is having trouble keeping up. Louise grabs the handles on the chair though, when they get to the curb right next to the vehicle, and she lowers the chair over the curb.

Vern and Louise were a team, so Vern walks over to the truck to see what was going on.

Louise is opening the rear doors and dropping the hydraulic lift.

“What’s doing?” Vern said.

“Cindy,” Louise says. “Cindy, this is Vern, my partner.”

“Nice to make your acquaintance Vern,” the person in the wheelchair says.

“What’s doing, Louise?” Vern says. “What’s the plan?”

“Nothing doing,” Louise says. “No plan. We’re going to give Cindy here a lift.”

The hydraulic whines as it lowers the gate. Same noise a garbage truck makes when it’s lifting the plastic garbage bins from the street. But maybe a little quieter.

“Okay,” Vern says. “To where are we giving Cindy here a lift? I don’t see a run sheet. I don’t see vitals.”

“We can do all that when Cindy is in the truck and secure,” Louise says.

“What is her particular emergency,” Vern says. “She short of breath? Or hallucinating?”

“Nope,” Louise says.

“So where are we taking her? Medical control involved?”

“Nope,” Louise says. “We’re taking her to my house.”

“Say what?” Vern says.

“We’re taking her to my house in Pawtucket. Take us ten minutes.,” Louise says.

“We can’t do that. You know we can’t do anything like it,” Vern says.

“Vern, this lady was up all night walking the streets to stay warm. It’s fifty-two degrees now. It’s going to be twenty tonight. She lost her husband and kid in a car accident two years ago. No life insurance. She lost her job at Carol Cable twenty years ago when the mills all got bought up and sent to China. Then she worked in 7-Eleven. Then she lost her apartment in Pawtucket because she couldn’t pay the rent on one income. Nobody can live on one income if you make minimum wage. You know that. She lived in her car for eleven months. Then her car broke down and she couldn’t afford to fix it. Then she lost her job because she couldn’t get to work. She has asthma and high blood pressure. We can’t let her sit out here like this. Maybe she’ll freeze to death, or maybe she’ll just get pneumonia. If she gets pneumonia, we’ll have to transport her to a hospital, and maybe she’ll live or maybe she’ll die, but we’ll have to transport her anyway, maybe once, maybe a bunch of times. And the hospital will bill somebody twenty times what it would have cost to pay her rent and fix her damned car. And Medicaid will pay the hospital to watch her die, even though nobody will pay to keep a roof over her head. I got a house with a spare bedroom on the third floor. It’s warm and dry there. So, we’re going to take her to my house. Like now.”

“She’s probably schizophrenic” Vernon said. Might be violent. You can’t just bring a homeless person off the street into your house.”

“You bet I can,“ Louise said. “Since when does being homeless or crazy deserve the death penalty?”

“These people, most of them started crazy and end up addicted. They think the world owes them a living. They chose this life. They like it,” Vernon said.

“You’re the one that’s crazy,“ Cindy said. “Stop talking about me like I’m not here.”

“Think about how much it costs to rent an apartment, how much people earn when they work, and all those old factory jobs that got moved to China. You think all that might have something to do with people being on the street?” Louise said. “I and you get paid every two weeks. Public money. Am I supposed to sit back and just watch Cindy and people like her freeze, and then die?”

“Amen to that, sister,” Cindy said.

“Most of them don’t die. They make out,” Vernon said.

“I don’t think so,” Louise said. “Sleeping in a tent or in your car in the winter isn’t making out. Standing on street corners when its raining, stamping your feet, trying to stay warm, that ain’t making out either. I can’t take care of them all and neither can you. But maybe I can give this one lady a break, until she gets back on her feet.”

“I don’t know who’s crazier. You or her,” Vernon said.

“You the only crazy person here,” Cindy said.

“It’s against regulations. You know that,” Vernon said.

“So, write me up. You get written up all the time. You’re still employed. And have a house and a car and enough to eat.”

“Giving people something they didn’t work for. Didn’t earn,” Vernon said. “That’s socialism.”

“ No it ain’t,” Cindy said. “That don’t have anything to do with who owns the means of production.”

“Nobody asked for your opinion,” Vernon said.

“Nobody gives a damn about yours,“ Cindy said.

“ I don’t care if it is socialism. Or communism or capitalism or anything else,” Louise said.

She hit the button and the hydraulic began to whine again, lifting Cindy and the wheelchair off the ground until it hit the level of the rescue floor. Then it jerked to a stop and the hydraulic stopped whining.

“The kingdom of God is within you,” Louise said. “We have not come into being to hate or to destroy. We have come into being to praise, labor and love.”

“When did you turn into a Jesus freak?” Vernon said.

“When did you turn into Attila the Hun? This is the United States of America. We don’t let people freeze to death on the steps of the State House.”

“No? Since when? Who are you, anyway?” Vernon said.

“There’s lots you don’t know about me,” Louise said.

‘Apparently,” Vernon said.

Louise went around to the side of the rescue, opened the doors, climbed the three steps and walked, bent over a bit to the lift, unlocked the wheelchair and rolled the wheelchair with Cindy on it into the truck. The she locked the wheels and secured the wheelchair, came down the steps, closed the doors and came to the back of the rescue. She flipped a switch. The hydraulic lift folded under the back of the truck, and Louise closed the rear doors.

‘You. It’s you we need to transport. To Butler. Like right now,” Vernon said.

“You can’t diagnose,” Louise said. “Outside of your scope of practice. You going to stand here talking all day? Or are you going to drive?”

“I’ll be damned,” Vernon said. He shook his head. But he got into the vehicle anyway.

–

Two days later, after 48 hours off, they got a call at about ten at night to an old house in Silver Lake. Vernon remembered when Silver Lake was mostly Italian, when people who looked like him weren’t so welcome there. It’s single-family houses there. Old single-family houses. Not like the triple-deckers that are packed into South Providence or Olneyville, where there is no place to breathe.

They have trees in Silver Lake. The houses are small and old, mostly bungalows, but they all have little yards and driveways and lots of them still have grape arbors and gardens, left over from the days when the Italian guys who worked in the mills in Olneyville would come home and work in their gardens after having a beer or a glass of wine, when they worked in their tee-shirts and tank-tops in the long days of spring and summer. Now those houses belong to Dominicans, Guatemalans, Hondurans, and Liberians, and now women work in those gardens in the summer. The houses aren’t quite as newly painted as they once were, and the yards have more junk in them now, bright green, blue, red, and white Big Wheels and other toys, but you can still see the pride people have in living in a house that is theirs, and having a little space around themselves, in the new cars and pickups that they parked in the driveways and on the street, BMWs and Acuras, some of them, with tinted windows and fancy rims, and in the Christmas decorations that were scattered about, lighting up the night. Those decorations weren’t the huge splashy displays Vern remembered from the old days. They were fewer, smaller, and more modest, usually just simple cascades of tiny lights hung over the porches and wrapped around the trees, but those lights send a message into the world: we are here, we are glad to be alive, we are proud to have come this far despite the odds — and that this is ours. Our house.

Vern was first out of the truck. He grabbed the jump box and was at the door in no time. A bald dark complected man in his forties answered the door and waved Vern and then Louise inside.

“Quick-quick,” he said and pointed to a room off a hall in the back of the house where a woman was moaning.

Four children, all younger than ten, the smallest with a big belly, sucking her thumb and wearing a diaper, stood in the hall clustered together, the whites of their big eyes glistening.

There was a very pregnant woman squatting next to a low bed, her knees open and spread in front of her, a blanket pooled with liquid in front and under her, her back against the bed and her bottom on the floor. She was writhing left to right and right to left as she arched her back, pushing in little jerks, in a way that was disorganized.

A blue-grey baby’s bum protruded from the woman’s birth canal. Just a bum. No feet yet. No cord. And no head.

Vern dropped the jump box and cracked it open. He started to put on gloves.

“Call for back up. And medical control. I’ll get vitals,” he said.

“How many weeks?…” he said to the woman and the man who had let them in and who was now standing in the room with them, behind the bed.

“You’ll do nothing of the sort,” Louise said. She came around Vernon and stood in front of the woman. Then she kneeled right in front of the woman’s bent knees.

“What’s your name?” Louise said.

The woman sat with her eyes closed. Her shoulders moved, jumping about.

“What’s her name,” Louise said, louder, looking at the woman, not the man behind her.

“Pri-cess,” the man behind the bed said. ”She na…”

“Doesn’t matter,” Louise said.

“Princess, lo a me na,” Louise said. Princess, look right at me now.

The woman on the floor opened her eyes for a moment, as Louise lifted each of the woman’s legs and put each foot on Louise’s ribcage. Then Louise took each of the woman’s hands in one of hers, her arms both outstretched, and grabbed the woman’s wrists, locking their hands together. The woman’s hand wrapped Louise’s wrists at the same time, holding on for dear life.

“We need to get this baby out NOW,” Louise said.

The woman’s eyes opened and locked onto Louise’s eyes.

Now PUSH,” Louise said. The woman pulled Louise’s arms as she pushed her feet into Louise’s ribcage with all her might. She let out a long low groan that came from deep in her gut. Her bottom shook with the force of all her back and pelvic muscles, all contracting at once. “AHHHHHGGGGG,” she groaned, a sound that came out of her back and belly more than from her chest or her mouth.

The woman loosened her grip. Her shaking legs stopped their thrust against Louise’s chest.

Louise looked down. There were legs out now, a belly, and an umbilical cord that was glistening, dark blue and yellow pink. Louise could see that this baby was a girl. But those legs and torso were still blue grey.

“Grab the baby,” she said to Vernon. Then that butt let loose a short stream of yellow-green liquid.

Vernon reached under the woman’s bent legs and caught the little warm body that was dangling there and supported it.

“One more big-big push-PUSH,” Louise said, not a shout but in her mom voice. Her outside voice.

The woman on the floor writhed and then grunted and roared as she put her back and her belly to work, as she pulled Louise’s arms into her and pushed with everything she had against Louise’s chest.

. “AHHHHHGGGGG,” she groaned again, louder and longer this time.

And then the baby was born. Into Vernon’s hands.

The woman in labor relaxed.

“Put the baby down and get me a couple of forceps or a hemostat or two, and a scissors. Quick-quick,” Louise said. “Breach baby. Asphyxiated. Not going to breathe. We got to do us a little resuscitation. Ambu-bag. Right now, quick-quick.”

She let go of the woman’s arms and put the woman’s quivering feet back on the ground, one after the next, moving as quickly as she could.

Vern carefully and gently laid that grey-blue stillborn on the blanket between the mother’s legs. He turned to the jump box. Louise turned to Vern to take whatever he could find and hand her.

And then suddenly, miraculously, the baby moved.

She sucked in with what seemed more like a hiccup than a breath.

Then that baby cried for the first time. The room filled with her new life.

When it was all over, after Louise cut the cord, swaddled the baby in a blanket, the father brought and put the baby on the mother’s chest to suckle; after Louise delivered the placenta and put the placenta and cord in a Ziplock plastic bag and labeled it with a Sharpie, writing the patient’s name and the date and time in the white space those bags have for writing; after they cleaned up a little, wrapped and boxed the woman and the baby, brought in a stretcher and loaded them both on their truck; after they told the father to meet them at Woman and Infants but please don’t follow the rescue– take time to find someone to sit with the other kids or at least pack them safely in a car; after they thanked their lucky stars that it was a one-story house in Silver Lake and not the third floor of a triple decker in Olneyville or South Providence; after they brought the mom and baby into the ED at Woman and Infants, grateful that it was now eleven at night so there wasn’t any traffic on the 6/10 connector even with all the construction; after they saw that the night was clear and the stars were bright in the cold air and that a waning half-moon was rising; after they gave report and restocked in the ED, the ED nurses not really caring about what Vernon and Louise had just done and lived through because they were having a busy night in the ED and they see precipitous labor and babies born in the field all the time – they went to get coffee and donuts. Or didn’t, because all the Dunkin Donuts were closed. So, they went for coffee at IHOP – not perfect, but all that was available.

“You were way, way outside of scope,” Vernon said. “There ain’t no protocol in the universe that covers what you just did.”

“Whoops,” Louise said. “Sorry about that. I personally am glad that baby decided to breathe. Protocols be damned. I don’t like dead babies. At all. I just hope we never have another one like that one.”

“How’d you know that shit? Getting her to push like that,” Vernon said. “It would have been hell on wheels, transporting a woman in labor, breech or no breech, the baby half in and half out. We would have had us a dead baby for sure.”

“Not my first rodeo,” Louise said.

“Seriously, where’d you learn that shit? ” Vern said.

“Some things you know as a woman, from giving birth. But I’ve also had friends and great teachers along the way.”

“What kind of teachers?” Vern said, “They didn’t teach you that in no hundred and fifty hour EMT course. I didn’t know you knew that stuff.”

“There’s lots you don’t know Vern. Lots,” Louise said.

–

There was a sudden cold draft. The front door of IHOP opened. A thin old man came into IHOP, shuffling, as though he didn’t have the strength to lift his feet. He was unshaved. His face was wrinkled and deep brown from dirt. The hair you could see was matted. He wore a dirty brown watch cap and carried two plastic shopping bags, or, more precisely two sets of many shopping bags, one packed into the next, and in place of shoes he had many pairs of dirty socks and cardboard tied onto his feet, and he wore many pairs of dirty socks on his hands.

He started going from booth to booth, not speaking, but everyone could tell what he wanted.

“Here we go again,” Vern said. “Everybody wants something for nothing. Nobody wants to work. Nobody wants to think.“

“Hey!” said a woman behind the counter. That caught the attention of a burly guy who was behind the counter as well, and who came out from behind that counter.

“Hey,” that man said. “Can I help you?”

The man just scrunched his shoulders and shook a little from side to side.

“Let’s go, buddy,” the man from the restaurant said as he turned the new arrival around and started walking with him to the door.

“Wait a second,” Vernon said. He stood up and went over to the man. He took his wallet out of his pocket, opened it, and put a bill in the man’s hand. Then he took the man’s arm in his and walked with him to the door, which he opened, and the man went by himself outside.

“I gave him five,” Vern said. “He’ll probably just drink it up. Or shoot it up. Whatever. What are you looking at? What are you gonna do?”

“We were lucky.” Louise said.

“You were lucky,” Vernon said. “I was just doing my job.”

–

Socialism. Noun. A political and economic theory which advocates that the means of production, distribution, and exchange should be owned by the state and used for the good of all.

Social Democracy aka democratic socialism aka regulatory democracy. Nouns . A belief that some degree of regulation of private enterprise by the state produces a more equal distribution of wealth and protects the health and other rights of its citizens. Social democracy recognizes that the for-profit actors in a free-enterprise economy sometimes place their own economic interests before the health and safety of others, and recognizes that effective democracy requires some degree of economic equality in order for citizens to have an equal voice in governance.

–

Capitalism. Noun. An economic and political system in which a country’s trade and industry are controlled by private owners for profit, rather than by the state.

–

Socialism – state socialism, the real kind, doesn’t seem to work that well whenever it’s been tried, and worse, it too often appears to lead to tyranny. Leaders emerge. Under the banner of creating social justice, making the work fair, eliminating poverty and injustice, those leaders make sure the machinery and power of the state accrues to themselves, and take away freedoms so they can protect what they always claim to be the common good, the needs of the people. Socialist economies also don’t work very well – they are too often rigid and bureaucratic, and stifle innovation and initiative. That said, small socialism, the kind practiced in some village agricultural societies, by religious orders of monks and nuns or on Israeli kibbutzim, for example, appears to work pretty well over time, giving people a secure life and organizing them to be economically productive, but also feels stifling to many people.

Unregulated capitalism also has its downsides. Try getting a human being on the telephone at a bank or a credit card company or almost anywhere else. That’s unregulated capitalism, which profits best by automating everything, by employing no one but still taking your money.

–

Not that a little free-enterprise ever hurt anybody. Much of our innovation, many new ideas and lots of community services are provided by people who do great work, appreciate their freedom to invent and to serve but expect to be treated fairly by others for doing so, and who build the resiliency of communities in the process. No one should want to take their freedom to innovate away, and government should just stay the heck out of their way. The problem comes when the innovators focus on growing bigger, when they find success and use their size and market power to eliminate their competitors, many of whom serve their communities, not just some distant shareholders, and that problem gets worse when these successful innovators turned businesspeople begin to shape, buy, or intimidate government to better serve their interests. Capitalism also leads to fascism and tyranny, as the big dogs use their money and power to maintain control over everything and everyone. (There is a strong argument buried in here to do the opposite of what the Supreme Court’s Citizen’s United decision did. Instead of calling corporations persons with free speech rights, we should likely prohibit corporations from making campaign contributions, from putting political ads on television and from lobbying at all!)

–

There is a downside to regulation as well, of course. Social democracy aka democratic socialism empowers a bureaucratic class, the people who cycle in and out of government, and use government to advance private agendas as those bureaucrats enrich and empower themselves.

–

Here’s how the regulatory process works in the US: a legislature – town or city, state, or federal, passes a law that gives certain powers to the government to regulate a specific business or social process, such as what waste a factory can discharge into the air or water, or whether schools can require the immunization of their students to protect the public’s health. Then people who work for that government write specific rules (aka regulations) that lay out how those processes should function and set penalties for people and the businesses of people who operate outside those rules. Note that the people who write these rules are government employees who themselves do not have to stand for election. They often belong to unions and have secure jobs. Thus, they themselves are protected from the demands of the marketplace, from having to make payroll and pay taxes on their profits, which may limit their understanding of and empathy for what business owners experience, and how their regulations may impact the conduct of business itself.

–

There is a process of public comment on those regulations, which regulators are required to consider, but in order to comment, you have to be large enough and be paying enough attention to know that a regulation has been written and to have a representative who can make a comment in a form that is effective and in the time period required: you have to be big enough to employ lawyers and lobbyists. So, the regulatory process itself favors the big fish at the expense of honest working people who are struggling to get by.

While regulation is sometimes believed to constrain the potential profits of entrepreneurs in a free-market system, it is also possible that regulation helps entrepreneurs, as a class, profit, by maintaining a level playing field for competition so that the economy as a whole grows: a rising tide lifts all boats; after the big fish swallow all the small fish, they starve; if you wreck the environment, your customers will all die off.

–

Like democracy itself, regulation is a hassle and a pain to deal with, but a regulated state may be better for most people than a laisse-faire state, in which the strong conquer the weak, in which most people end up suffering so a few can live like kings, and money talks but nobody else walks.

–

Corporate entrepreneurs want you to think that regulation is socialism, which it isn’t. That’s how they convince people and their elected representatives to avoid regulating them as they grow, or to deregulate, so the entrepreneurs can profit, upending democracy in the process, because the more entrepreneurs profit, the more they can use their money and bought political power to further enrich themselves.

–

That said, regulation restricts people’s freedom, but it restricts the freedom to profit much more than the freedom of speech, the freedom to associate, the freedom to petition the government, the freedom to move about or think what you want and associate with whom you want, all by way of rules people or their representatives did not vote for themselves. Most people think they cand do without regulation, at least until someone they know or some corporation, they don’t like does something that hurts someone they know or love, or just ticks them off.

–

People hate regulation until something goes wrong. Then they say, the government failed to protect us: something must be done! Everyone hates the status quo but no one likes change.

Maybe we’d be better off if we all paid a little more attention to government, and everyone did their part, stepping up to take a turn in government, trying to figure out how to manage for the common good. But that doesn’t seem likely. People want to drink beer, watch football on TV, hang out with family and friends, or surf the internet. That’s just who we are, like it or not.

–

But socialism on the rise? Socialism can’t be much of a problem, because we don’t have anything like a socialist economy in the US, despite what pundits and scaremongers would have you believe. Bring socialism here and it might give rise to some headaches. But that’s not what we’ve got.

Unfettered capitalism is a problem for us because we live in a capitalist economy and are subject to its excesses and abuses. The crazy people who keep sending me emails saying this one and that one is extreme or radical or a socialist or a colonialist, they aren’t the problem either, most of the time. They are just a distraction. And pretty boring.

–

The problem is that we aren’t that smart or motivated, that all of us want more than we are willing to work for, and all of us want more than we probably deserve. The miracle is that most of us get to live our lives in relative peace, that the sun keeps coming up every day, that there are flowers and trees, and we haven’t completely wrecked the planet yet, and that most of us actually have way more than we deserve, despite ourselves.

–

So which economic system makes most sense? None of them! We get it wrong, miss the mark, allow excesses and abuses all the time. Good intentioned people often overreach. Perhaps always overreach. Bad-intentioned people are always looking to find a way in, to find an opportunity to exploit, or stretch the truth just enough to distract most of us and give those bad-intentioned people the space they need to take more and more for themselves. Both good and bad-intentioned people are riddled with self-deception, and rarely tell themselves the truth about who they are or about the impact of what they say and do. We have lots of ideas. But no humility.

Our challenge, then, is to think critically, believe nobody, watch for results, stay engaged despite the hassle of doing that, take turns in government but never stay too long, make sure we have as much freedom as we can get and defend the freedom we have by speaking truth to power, and by voting, but also by making sure we stay focused on the common good and on building resilient communities. Despite ourselves. Our challenge is to listen to people more than to ideas and to remember that ideas, corporations, and governments themselves are not people. Our challenge is to look other people in the eye, walk their walk, imagine ourselves in their shoes, and remember that only people matter.

–

Churchill said that democracy is the worst form of government except for all the other ones. To paraphrase Gandhi, democracy is actually a great form of government. Maybe the kind. We should try it sometime.

–

All of Michael Fine’s stories and books are available at www.MichaelFineMD.com or by clicking here. Join us!

___

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor in Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.

He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.

He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.

Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.

_