Search Posts

Recent Posts

- GriefSpeak: Waiting for Dad – Mari Nardolillo Dias June 13, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 13, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 13, 2025

- Urgent call by Rhode Island Blood Center for Type O- and B- blood June 13, 2025

- Real Estate in RI: Ready, Set, Own. Pathway to Homeownership workshop June 13, 2025

- Outdoors in RI – Risky cattails, Fight the Bite mosquito report, 2A gun ban bill update June 13, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Home Sweet Home – a short story by Michael Fine

By Michael Fine

© Michael Fine 2021

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

_____

There was nobody Glenn Shandy wanted to hear from more than his big brother Jack. And less. You had to respect Jack regardless of his attitude. He walked the walk. Cop again, after three tours in the Guard – Afghanistan, Iraq and then Afghanistan, again. He never bitched but he didn’t talk about it either. He never lorded it over you. But you always knew it was there. He thought he was better than Glenn. Better than everyone and anyone.

That meant Jack wasn’t anybody Glenn wanted to spend regular time with. They were together enough as it was. Weddings and Christmas. Sometime Thanksgiving and New Year’s. Sundays about once in six weeks. They were a big family – seven brothers and sisters — so they passed holidays around. Even so there were too many of them to be together with any regularity. Glenn saw Jack plenty, and maybe more than enough. All that cop shit, that we know what’s best for you shit, that, and now the get the guns off the street stuff. You’d think he never heard of the second amendment. And that he didn’t know about what was out there, that he didn’t get the rot on the street and how the country is falling apart. You’d think all that snowflake shit didn’t bother him, the Black this, and Latino that, and the theys and the thems instead of he and she, all those idiots and college professors who didn’t know who they were and what they stood for, all those immigrants and people so blinking worried about who they wanted to love. Jack was a standup guy, maybe, but he had a hyphenated last name now, so he was complicit, he was part of the problem. There was trouble coming, that was sure. Glenn was ready, and he’d be ready to help their parents and their brothers and sisters when the time came, whenever, wherever, and whoever was going to be the problem when the shit hit the fan.

So, when Jack called and said, can I come over, Glenn said sure, you’re my brother, you can come over anytime. Maybe he’s got a new gig for me, Glenn thought. Jack was always looking out for him, just like he looked out for all of them, and Jack always had a new gig going somewhere, painting houses or doing lead inspections, some new side business that put money in his own pocket and in the pockets of half the men in the rest of the family. But maybe there is trouble in the family I don’t know about, Glenn thought; maybe one of Billy’s kids going gay or trans or maybe Sarah is about to dump the boyfriend of the month, again.

But maybe, just maybe, Jack has started to see the writing on the wall. Maybe he has had just a little too much of all this shit, and maybe he’s starting to see it my way after all. Maybe he wants to get ready with me and wants to know what to do and who to talk to. It’s way past time for that.

___

Glenn was out by the barn when Jack drove up. Big black Lincoln Navigator. Exactly what you’d expect Jack to drive. No pickups for Jack. Nothing subtle or regular. Had to be the whole nine yards. Always the whole nine yards.

Glenn was splitting wood next to the barn. He cut, brought in and hand spilt twenty cord a year. Heated the old house with wood and was proud that he could do that, with the strength of his arms and the power in his legs and back. Energy independent. No foreign oil. No money to Arab Sheiks. Off the grid.

The barn wasn’t a barn anymore, truth be told. It was a garage and a shop. There was a two-bedroom apartment on the second floor where the hayloft used to be, where Glenn figured his kids could stay when they came to visit. If they came to visit. Whatever.

Sometimes Glenn rented that apartment out. But sometimes, like now, he left it empty, because he just didn’t want the hassle of leases and the constant negotiation that you have when you have a tenant. He also didn’t want other people around the place, with what was going on in the country and so forth. You don’t know who is who. You just don’t know who you can trust. If anyone at all.

___

Jack got out of the car. Then two other doors opened and closed. Two other people got out, a woman and a kid. The woman was wearing a white head scarf. With jeans and a bright red top. The kid was a boy. Maybe ten, maybe twelve. Thin and brown. Glenn swung his maul one more time, so it stuck in the chopping block. He left it there, head in the wood, handle pointed up.

“What gives, Jack?” Glenn said, looking over his glasses at the woman. She was thirty-something. Maybe forty. Dark brown hair streaked with grey. Dark brown eyes. She didn’t hang back. Walked next to Jack, not behind him. The kid walked next to her.

“Hey Jack, nice to see you, brother. Welcome to my home,” Jack said.

“What gives, Jack? What’s this all about?” Glenn said.

“This is Khalilah. And Ahmed. They’ve been up all night,” Jack said.

“Congratulations. Too bad for that. What gives, Jack?” Glenn said.

“Their plane got to Logan at 2 AM. Can you be nice for once?” Jack said.

“I am nice. To my friends,” Glenn said. “When I wanna be. Plane from where?”

“From Kabul,” Khalilah said. She looked directly at Glenn. Her English sounded clean enough. Her accent was difficult to place but what can you tell from two words.

“So, what gives, Jack?” Glenn said. “Afghanistan is a disaster build on a disaster. Your senile puppet president strikes again. Quicksand, not just the swamp. What do you want? Why is this my problem?”

“I need to stash Khalilah and Ahmed for a couple of days,” Jack said. “In the apartment over the barn.”

“Which you know is empty?” Glenn said.

“Which I know is empty,” Jack said.

“I do nothing but take care of these people all day and all night at work. Isn’t that enough?” Glenn said.

“You don’t take care of me at work,” Khalilah said. “You haven’t met me yet.” The accent was American. Midwest? Cleveland or Buffalo, maybe Chicago. And this woman was not shy. That sure as hell didn’t make no sense. Attitude. No begging. But no shame.

“There’s a pandemic on,” Jack said. “I need them out of harm’s way until we can get them immunized and find them a place.”

“What a bunch of crap,” Glenn said. “A made-up disease. A bullshit shot to make the Wall Street trash richer. A stupid war which you were stupid enough to go and fight. And now the mongrel hordes, invading America again. You think there might be a pattern here? When is all this shit gonna stop?”

Jack waited.

“All right. They can have the apartment for a couple of days,” Glenn said. “But I’m not Uber or Lyft. I’m not ferrying people around. And I’m not cooking for anyone.”

“Good,” Jack said. “I’m trying to help them out, not kill them. Got groceries in the Navigator. I’ll do any driving they need. You got to work.”

“Damn straight I got to work,” Glenn said. “I got a twenty-four starting in the morning. Which could go to a forty-eight. Don’t count on me for nothing. And you people, you stay in that apartment. You leave my shit alone.”

“Thank-you,” Khalilah said. Then she nudged the kid.

“Thank-you sir,” the kid said. His voice was high pitched like a girl’s. He spoke good English as well but there was a little foreign in it. He hadn’t grown up in Cleveland, that was for sure.

“Don’t thank nobody yet,” Glenn said. “This is Jack’s doing, not mine. And who knows, maybe I’ll kick you out tomorrow, once I’ve had twenty-four hours to think about it.”

“Since when do you know how to think?” Jack said.

That guy. So damned full of himself. Lord only knows what the real story was. Who was she to Jack, who always had a couple of irons in the fire? Was or had been. How the hell did Glenn always let him get himself dragged into Jack’s messes?

___

There were no fires that night or the next, but EMS still ran all night long, ten calls in twelve hours, a little break in the morning, but then it started up again. Two ODs, one with the needle still in his arm, a Latino guy they got back with CPR and Narcan; the other, a woman in her twenties with lots of tattoos, they didn’t get back. A chest pain. A shortness of breath. A woman in labor. And four or five crap calls, the I-ran-out-of-my-medicine or the President-Trump-is-calling-to-me-from-my-microwave-ordering-me-to-kill-Mexicans kind of calls. Man-down calls, for drunks who refuse transport anyway. Lots of immigrants. Liberians. Hmongs. Dominicans. People who can’t trouble themselves to learn English, so you can’t talk to them. Who cares why they call anyway? Lots of sore throats and runny noses. Now you have to suit up for every one of those. The damn PPE takes forever to put on and take off and is hotter than bejesus. Nobody thinks for themselves anymore. No one takes responsibility for their own choices. It’s a gimme this, gimme that world. You always got to watch what you say, what you think, who you are talking to, every effin’ moment. And they call this freedom?

___

A couple of guys called in sick and the twenty-four turned into a forty-eight, after all. Same shit, different day. Witness to the apocalypse. But what the hell, the overtime was good. Forty-eights suck but each one brought Glenn a little closer to retirement. Retirement, pension at fifty, and then some other, more cushy kind of job. Be the safety director of one of the colleges. Work in a lumber yard. Run security for a country club. Nine to five. Play a lot of golf. Something like that.

___

Now Glenn was just dog-tired and sleep-blind. All that mattered was hitting the bed.

He’d forgotten about the woman and the kid. Until he rolled into his yard midmorning and saw the kid next to the woodpile.

There was his axe, right where he left it.

Damn, Glenn thought. I left the axe stuck in the chopping block. Should put it away. Good thing no one touched it.

But the pile of split wood he’d left when Jack drove up and distracted him, that was gone. The kid was standing there next to the chopping block. Somebody had stacked all the split wood in the woodshed next to the barn. Likely that kid. Pisses me off, to have that kid messing with my shit, Glenn thought. They were supposed to be invisible, to be neither seen nor heard. Jack’s problem, not mine. But there he was, a scrawny little brown kid, hanging out next to the barn.

The kid had big brown eyes; the same eyes Glenn remembered the kid’s mother having.

Then the kid disappeared.

Glenn stamped into his place, tore his clothes off and stumbled into bed.

___

And was awakened by the light streaming in through a west-facing window, the astounding red light of late day on his face, that strange, almost mystical light that finds the inner meaning of things in the colors they always had, but that late summer late afternoon night somehow magnifies, somehow finds in a new way. Red, now brilliant, warm and too hot to touch, all at once. Green, now warm and wise, almost lusty. Yellow, suddenly hot. Orange a deep heat, a passionate hotness. Blue, dusky and bold. Secure and as solid as the earth itself. Brown, thunderous and all knowing, the skin tone of the everlasting earth.

“Halloo!” a voice called. There was knocking at the door. Glenn was still stuporous from sleep, and he shook his head, unsure if he was awake or dreaming. But the knock came again.

“Halloo!” the voice said.

There was a woman and a child. Glenn remembered now. A Jack thing. Jack had parked them in the barn apartment. And Jack was looking after them. Supposed to be. Damn well better be. Not Glenn’s problem.

___

‘What’s the story, Eddie?” Glenn yelled. He pulled on his pants, stuck a cigarette in his lips, lit it, and stumbled to his front door shirtless, the butt hanging from his lower lip.

There she was, that woman Khaliah, headscarf and all, looking fresh and brilliant like she’d had a good night’s sleep or come back from a long run on a cold morning, showered and washed her hair; those deep brown eyes full of life and all-knowing, ready to conquer the world. That headscarf was bullshit. You could see her hair, that dark brown hair, and that dark tan skin, the deep brown, almost black eyes set against the white headscarf in the brilliant and all illuminating light of the setting sun – Glenn had never seen as beautiful a woman anywhere. And Glenn, standing there in the doorway with no shoes and no shirt, a cigarette butt hanging from his lip, the smoke curling out of his nose, stinking, stale and moldy, in a house that no one ever cleaned anymore because no one ever came to visit. Just him. An old white guy. Pissed off, mean as a Gila monster and ready to defend America when push came to shove, which is going to be any day now. Don’t you tread on me. Don’t even think about it.

“Can I borrow a cup of sugar?” the woman said.

___

And that was it.

Glenn fell for her, Lock, stock and barrel. Right then and there, with her standing on his front porch. Right in the face of everything Glenn knew about the world and everything he believed. Or didn’t believe in. Despite everything Glenn knew about what was fuckin’ up the country. An immigrant, God-damn it. A Muslim. A woman with a kid, even after Glenn promising himself that he was done with families and kids. He’d rather have a dog. But he didn’t want a dog either.

___

Suddenly the emptiness of Glenn’s life became clear to him, and he wanted this woman in his life right then and there, now, and forever.

“Come on in,” Glenn said, not understanding yet what had just hit him. He punched his cigarette out on the doorpost, holding it behind his back. “No, Wait. Stay there. House is a mess. I’ll get your sugar.” He backed away from the door, and disappeared into the darkness of the house, back into his room. He found an old denim shirt and put it on, ran his fingers through his hair liker a comb, and then came back to rumble about the kitchen, looking for sugar. Who the hell knew if there was sugar in his house? He didn’t bake. Drank his coffee black. No one had thought about sugar for one second in the eight years he had been living alone. That was a woman thing.

Khalilah looked through the screen door into what looked like a cave or a tunnel, through a dark living room and a hall, the kitchen set at the back of the house, itself lit by a bay of windows next to a sink, dimly illuminated by the waning light. She heard thrashing about, the sound of doors and drawers opening and closing, of dishes being moved and pots clattering.

Khalilah assumed that this man would be like Sergeant Shandy-McCoy, all spit and polish, pompous and self-congratulating but also organized, neat and clean and well-funded, if somewhat daft, self-absorbed, and completely naive about how the world actually works. Americans think all culture is tribal. Everyone else in the world understands the reality of community, family, tradition, and honor, which is how the rest of the world lives.

But this man was different. There was no pretense about him. What you saw was what you got, apparently. He had abandoned all hope. And there was much that needed fixing in this house, and so it seemed, in his world.

___

When Glenn came back carrying a yellow and blue carboard box with a rusted metal spout that looked like it could be ten years old, with a denim shirt on only half-buttoned and his salt and pepper hair smooth back but still uncut and unruly, with the cigarette gone and the smell of peppermint mouthwash about him, Khalilah felt something she didn’t expect to feel again, and particularly not so soon, after the loss of her people, her county, her hopes and her world.

___

“It’s sugar,” Glenn said. “Don’t know if it’s a cup. Hard as a rock, but it should break up pretty easy. I can get you a hammer if you want.”

“Let me try it without the hammer,” Khalilah said, the white headscarf blowing in the evening’s warm wind. “I’ve bothered you enough. We’ll make do. Thank-you. I hope I didn’t disturb your evening.”

___

It was an American accent after all, Glenn thought. Maybe California. But it has a music to it, a lilt and a lift that our talk don’t have. Pretty. Like the rest of the package.

“Not a problem. What do they say now? Da nada,” Jack said, and then he kicked himself inside his head. Stupid fuck, he told himself. That’s Spanish. She’s Afghan. God only knows what she speaks. She must think I’m a racist dolt.

“Grazie mille muy amigo,” Khalilah said. She smiled to herself as she turned away. This man has no idea who I am or what I am, she thought. Or what language either he or I am speaking.

But he does have a certain rough-cut aboriginal charm.

That was all it took.

___

It turned out the boy’s father was a French photojournalist who Khalilah met in Paris, who followed her home to Afghanistan when she went back, after it looked like the Americans might stay for a while. She knew it wouldn’t last, not Ahmed’s father and not the Americans. She should have left as soon as Trump announced the Americans were leaving, or the moment that Biden suggested that there wouldn’t be one more American flip-flop. Which of course meant there would be that flip-flop.

The U.S. Government turned out to be even more ham fisted, bureaucratic and ridiculous than Khalilah thought. Getting documents proved impossible. There was that crazy situation at the airport, that collapse like a hundred others in history, when governments fail and people go streaming for the exits, when anything can and will happen — all sorts of human dramas when you see and experience the truth of who people really are: who has courage, who integrity, who honor, and who selfishness, greed, cowardice and deceit hiding in the inner recesses of their souls.

They, Khalilah and Ahmed, they didn’t get out until the last minute, even with Sergeant Shandy-McCoy hounding the State Department for them. Which he did. Thankfully. Amazingly. Even though Khalilah had turned him down, once upon a time, when they worked together at home.

At least Khalilah and Ahmed got out with their lives. And could start over, more or less, after mourning the loss of their people, the loss of hope for their nation and for a different future. Gut-wrenching. Heart-breaking. But kind of a miracle even so.

___

None of that mattered to Glenn. Khalilah was drop-dead beautiful. She had a soul as deep as the ocean, even if she did laugh at him for his way of simplifying all ideas to a few simple ones, for his lack of sophistication. Glenn even liked having the kid around the house. The kid was anxious to learn. He sopped up attention like a puppy.

Maybe there are second chances, Glenn thought. Maybe he’d be able to do for this kid everything he had failed at with his own kids, who had pretty much disappeared from his life when their mother walked out on him eight years before. And should have. Because he got ornery and mean as he got old and probably didn’t deserve any of them or anything he had. Burned out. Pissed off. Selfish son of a bitch. Don’t you tread on me.

___

The kid followed him around like a puppy when they were home together. Chores were chores. Glenn had a lawn to mow and an old pasture to cut, a garden to weed, a stone wall he had been working on finishing for the last ten years, the old orchard on the hillside that he was trying to bring back from oblivion, and wood to bring in, split and stack. The fences were long gone, the posts rotting at their bases, with barbed wire flopping this way and that, but Glenn had stopped caring. So now there were the fences to fix as well.

When Glenn mowed, Ahmed just stood there his hands on his hips, his brown skin glistening with sweat in the later afternoon summer sun. Or he followed Glenn into the garden when Glenn hoed the ground around the tomatoes. Eventually Glenn found Ahmed a rusted hand cultivator to use. Ahmed knelt and cultivated close to the plants, close to the tomatoes, the squash, and the eggplant, while Glenn chopped weeds in the hot brown dirt between the rows.

The kid didn’t say much. He worked with focus and intensity, his small hands busy in the dirt, pulling out grass or weeds by the roots when he could. Glenn didn’t say much either. He marveled at how this kid could work. None of Glenn’s kids ever followed him into the garden. None of them would mow the Goddamn lawn, take out the garbage or even wash the dishes, regardless of how Glenn hounded them. Their mother didn’t care one whit about things like teaching kids how to work and how to be responsible adults. She was just fine with them watching TV. Or sitting on the computer, later. Or sitting with their cell phones, at the end. That was all she expected from those kids and from herself. You reap what you sow.

___

One day in October when Glenn was splitting wood and Ahmed was watching him, Glenn’s cell rang. He ignored it once. Then his text chime when off. He ignored that too. We are like trained dogs, Glenn thought. Or rats in a maze. We do what they tell us to do. They ring a bell or buzz a cellphone and the world stops for us. Then we jump when they say jump. Usually so they can sell us something.

Then a few minutes later the phone rang again.

It was just Celeste. Was it safe for her to go to dinner with old friends? Covid and all that. Their old friends. A dinner to which Glenn hadn’t been invited. They had been divorced eight years. Glenn was an EMT and a fire-fighter, not a doctor. That woman still couldn’t think on her own.

When Glenn came back to the woodpile, Ahmed was having a go at the round of oak Glenn had been splitting. Ahmed could barely lift the maul, let alone swing it. Poor kid. Those little brown arms. He tried dropping the maul on the oak round from about six inches above it. Nowhere near enough height and no force behind it. The maul bounced off and slid to the ground. Didn’t even stick in the wood.

“Here, let me show you,” Glenn said. He pulled the maul into the air. “Stand back. Stand at least six feet away.”

He swung the maul, a simple thrust of his arms, shoulders and back, bending at the waist, with a sudden flick of his wrist. The maul popped through the wood, and its two halves went flying in opposite directions. Like a knife through butter. Sweet. And this was oak. Glenn knew how ash would have split. Easier yet. Even Ahmed could have split ash. Maybe. In a year or two, anyway.

“See? Easy,” Glenn said. “You just got to learn how to stand. You can’t be scared of it. You’re the man in charge. You’re the man of the house. But you need to work those muscles, boy. Get yourself a set of biceps.”

“Like this?” Ahmed said, and he flexed his right arm to make a muscle, smiling but with real sadness in his eyes. His arms where thin. The muscle was barely a bump.

“Yeah, like that,” Glenn said. “Don’t worry. It’ll come. It always does. Just takes a little time.”

Glenn slapped a blade guard on the maul and swung it over his shoulder. Teach the kid right. Teach him to take care of his tools.

“Now help me stack. You’re good at that. Then I’ll show you how to light the wood furnace. No boy I know doesn’t like to play with fire at least a little.”

___

Eighty percent of fire calls aren’t fires at all. They’re EMS runs. You train and you train for fires. But most of what you do is roust up drunks passed out on the sidewalk or loft up little Spanish-speaking men and women scared about their chest pain, who say “Pecho, Pecho!” and ‘Dolor, Dolor!” over and over again. They put their hands on their chests but calm right down as soon as you get them in the bus and the O2 on. Normal EKGs, every single one. They live for the ride to the ED, or that’s what it feels like. They live to be sick. That’s who they are. They get pleasure from it.

So, a fire call is a big deal, and a real fire call is a bigger deal yet, because most of the so-called fires people call 911 for are crap. The oil on the stove caught fire. Somebody left a pizza box in the oven and turned the oven on. There was a fire in an ashtray. An old table fan starts sparking and maybe it burns for two minutes, a fan with frayed wiring they should have thrown out twenty years ago when the insulation on that wiring cracked and fell off.

The first alarm, in Coventry, didn’t get anybody jacked. There are a bunch of old mills in eastern Coventry near the West Warwick line, out 117. A good mill fire is more of an opportunity than a risk. Half of them are friction fires – what happens when the mortgage rubs up against the insurance policy — although everyone remembered the stink of the burned foam and roasted flesh from the Station fire, which was part of the collective trauma of every first responder in Rhode Island, baked into everyone’s DNA, something you live with every day. Glenn could still smell it all these years later, the stink of it tattooed high up in his nostrils, right next to his brainstem.

But most of those mills are deserted now, so you don’t worry about loss of life. You check for signs of habitation, to make sure there ain’t some homeless squatting inside. If there’s nobody, then you just make sure the damn fire doesn’t spread. You stand back and don’t do anything stupid. You gear up and run a controlled burn. Good practice for the real thing. You don’t play the hero. No charging in with seventy pounds of gear. Those mills ain’t the World Trade Center with three thousand people on the top floors. Buildings are just buildings. Lives are different. You just let the building burn so long as nobody is trapped inside.

By the second and third alarm, Glenn started to listen out. His boys started to suit up. Their turn was coming.

Then somebody said western Coventry. A converted barn. Twenty cords of wood stacked and dry as a bone. One of those outside wood burners. 128 million BTUs in a cord of hickory. Four million BTUs in a one ton of TNT. Twenty cords of wood with as much firepower as 640 tons of TNT, all going up at once. There are tactical nuclear weapons with less firepower.

Western Coventry.

Holy shit, Glenn said. That’s my house.

___

The house was toast by the time Glenn got there.

You could smell it a mile away – the bitter stink of charcoal and the diesel exhaust smell of roast PVC so thick it burned his eyes and lungs at once, the murky smoke, thick as soup. His road was filled with apparatus, with every fire truck, police car, and ambulance for miles around, their red, white, and blue lights flashing silently, eerily, emptily. Glenn dumped his truck at the turn-off because the road was now closed. He ran the distance in his boots and jumpsuit, his helmet in his hand, just in case. His eyes burned and his brainstem seized up – that stink of the Station fire and 911 again, still tattooed in his bones and in the fat lining his heart.

Damn it to hell, Glenn thought as he ran. Goddamn Jack. He got me into this mess. Immigrants and wars and government bureaucrats. Now I’m going to have to deal with FEMA and the Red Cross and all sorts of people, just to get my Goddamned house fixed. That kid. I should never have…. I’ll give that kid and his mother a piece of my mind when I get my hands on them. They’ll be at a neighbor’s. Or maybe the Red Cross has them by now.

___

Then he rounded the corner into the driveway

There was no house.

Charcoal. Embers. Ash.

Nothing left. Nothing. The barn, the house, the fences, the tractor, the ATV, the boat, the grill, even the old above-ground pool gone. All vanished. Vaporized. All of it.

There was a chimney standing in the shouldering ruins. Black, maybe five or six feet of it left, crumbling but standing. The remains of washer and dryer, also black, collapsed in on themselves a few feet from the chimney, all that was left in the black ash and glowing embers, like tombstones on a vast prairie. The tractor and the ATV, their tires melted, blackened, on their sides in the ash, the ATV ripped apart when its gas tank exploded. All that remained of trees for a hundred yards around were smoldering stumps.

___

The guys had an incident command center set up out on the street, just south of the driveway entrance. They’d thrown up a tent between a hook and ladder, a hazmat truck, and a couple of police vehicles.

But everything else had been incinerated. The earth itself was black, the grass burned to a crisp, the black ash and charcoal scattered about as if it had been spread by a seed spreader. Pieces of sheet-metal roofing lay on the ground, warped, and twisted. The black earth glistened from the shards of broken glass that were everywhere, as fire fighters sprayed gallons and gallons of water from the pump trucks on the site, and one pump truck rolled up after the next. The guys shouted orders and instructions to one another.

Glenn looked for an instant. It was a holocaust. No place to run. No place to hide.

___

He spun around.

Khalilah. Ahmed. Where they hell were they?

Suddenly it felt like all his insides, his guts and heart and lungs had been ripped out, twisted like a rope, and burned to a crisp in that fire.

___

That was when he saw them. They were standing in the Command Center, waving to him weakly, their faces drawn and smudged, and their clothes torn, Khalilah’s head scarf now brown and grey with soot.

He ran to them and fell on his knees. Wrapped his arms around them. Then he stood and walked away. He couldn’t let them, or anyone else, ever see tears. No one would ever see Glenn weeping. Not now. Not ever.

___

Stupid kid, Glenn thought. He was sure the kid had started the fire.

But it doesn’t matter, he thought.

Who cares what the kid did? Who cares if the house and barn were gone? Who cares if everything had turned to ash and charcoal?

They were home.

You can always build another house.

The earth was black.

But everything else was still possible.

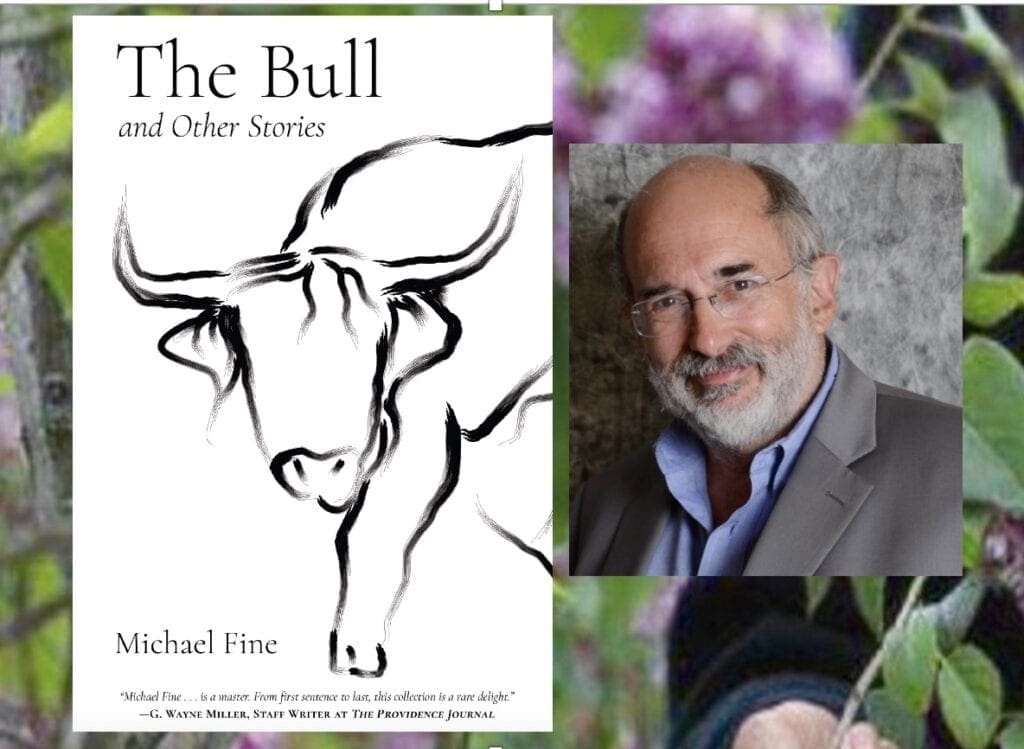

All of Michael Fine’s stories and books are available on MichaelFineMD.com or by clicking here. Register there and we’ll send you a new free story every month.

_____

Michael Fine, MD, is a writer, community organizer, and family physician. He is the chief health strategist for the City of Central Falls, RI, and a former Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health, 2011–2015. He is currently the Board Vice Chair and Co-Founder of the Scituate Health Alliance. He is the recipient of the Barbara Starfield Award, the John Cunningham Award, and the Austin T. Levy Award.

He has served as Health Policy Advisor to Mayor James Diossa of Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He facilitated a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.

He was named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.

He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.

Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.