Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Outdoors in RI: Help keep recreation areas clean. Invasive Milfoil, trash. 2A update – Jeff Gross July 26, 2024

- Real Estate in RI: Highest-ever sale in Queen’s Grant, EG $1.25M, by Residential Properties July 26, 2024

- Homeless in RI: Gov. Newsom issues Executive Order. Remove California’s encampments. July 26, 2024

- Let the games begin. XXXIII Summer Olympics – John Cardullo July 26, 2024

- GriefSPEAK: What would you do? – Mari Dias Nardolillo July 26, 2024

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

GriefSPEAK: The thief that steals us: ALS – Mari Nardolillo Dias

By: Mari Nardolillo Dias

“I got my first real six-string

Bought it at the five-and-dime

Played it ’til my fingers bled

Was the summer of ’69…

Man, we were killin’ time

We were young and restless

We needed to unwind

I guess nothin’ can last forever – forever, no” (Bryan Adams)

Sebastian is a 50 year-old lyricist and guitarist who prides himself on not caving to mainstream music, and who has been religiously committed to his originals for over 30 years. Sebastian recited the quote above, as he remembers playing and practicing guitar until his fingers bled. Music was, and is, his life. We texted for a week or two, spoke a few times on the phone and planned my first visit. Sebastian explained that he had some weakness in his left leg about a year ago. He began to stumble, trip, and sometimes fall. The preliminary diagnosis was Parkinson’s disease; however, it wasn’t long before his right leg began with the same weakness. Doctors ruled out ALS. Yet, the weakness continued and in a short time it attacked his arms. He was scared, but relieved that he could still play his guitar. A second opinion in Boston revealed his biggest fear – it was, indeed, ALS. Sebastian was told his condition could last for years, and the progress of his particular condition was unknown.

“It depends on the patient, and the progress of the disease.”

Sebastian knew that his symptoms were rapidly progressing in a very short period of time. It was less than a year before he was bedridden, lying in a nursing home, always with his Alexa, cell phone, and guitar as constant company. When I arrived on our first visit, I noticed that he has his call button taped to his pointer finger. He was sweating and hoping for a cold cloth. As I attempted to locate a facecloth, I noticed his towels and linens were still dry. It was 2 pm in the afternoon and he still hadn’t been washed. I proceeded to put a cold compress on his head, combed his hair, and asked if his stubble was a personal choice.

“No.”

I performed some soft touch stretching with his arms and legs. He could feel my touch but couldn’t move. He played several of his original songs that contained profound lyrics and a jazzy riff about facing his fear of losing his ability to communicate and finally, inability to breathe.

I was compelled to ask when he had last been out of bed.

“About 3 months ago.”

I was shocked but chose not to share my reaction.

“Is that by choice?” I asked.

“No, replied Sebastian. “I would do anything to just go outside in a wheelchair and feel the air!”

“There must be a Hoyer lift in the nursing home to get you out of bed and place you in a wheelchair! I’ll take you outside!”

There wasn’t a nurse to be found that wasn’t running around caring for other patients. There was a shortage of nurses and a stringent COVID protocol which deleted the amount of visitors. I left feeling hopeless but not helpless.

The following week I texted Sebastian concerning our next visit. He didn’t answer. I followed the text up with a phone call, and in garbled speech, Sebastian told me he could no longer text and he was losing his ability to speak. I heard the implied. He couldn’t play guitar any longer, and soon would not be able to communicate.

I remember reading a book entitled “The Diving Bell and the Butterfly” by Jean Dominique Bauby, who had a stroke at age 43. He suffered “locked in syndrome”, a condition where, in his case, he was completely paralyzed except for his ability to blink. According to the description of the book “Bauby painstakingly dictates his memoir via the only means of expression left to him.”

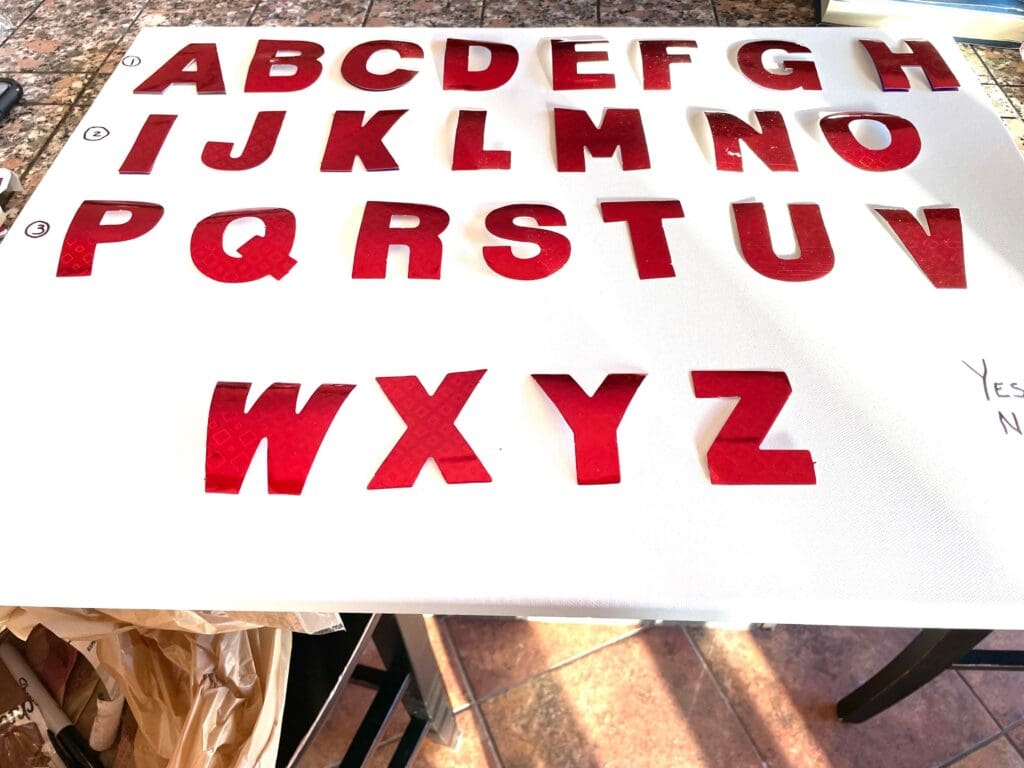

I decided to do the same for Sebastian, offering an alternative method of communicating. I made an alphabet board, and an extra Y (yes) and N (No). I planned to follow the protocol that Bauby’s nurse employed. I hoped and prayed Sebastian was still able to blink.

On my next visit, Sebastian could no longer move or speak at all, but he could blink with one eye. He heard and understood everything I said. I explained the alphabet board:

“Sebastian, I am going to point to the letters on the board, and when I reach the first letter of the word, blink. Keep going until you spell out what you want to say. I know you cannot nod or shake your head, so if I ask you a question, I will simply point to the “Y” or “N”, and you may blink when I am correct!” As we continue to work with this, we will be able to complete it more quickly. Jean-Dominique Bauby wrote an entire book this way. Would you like me to read it to you?”

I pointed to the “Y”, and Sebastian blinked. I have been reading and communicating with Sebastian for the past two weeks. ALS steals our abilities, one by one, and for some, simultaneously.

ALS steals our abilities one by one, and for some simultaneously. The irony is that in most cases it leaves our mind intact.

Sebastian still has not been out of bed, and his guitar “gently weeps”, sitting idly in the corner. In Sebastian’s case, his ALS progressed very rapidly, but he still has the ability to blink. And breathe. Small miracles. It’s important to provide respect and dignity at end of life. Sebastian is not dying; he is still living. And for that I am grateful. And he, appreciative.

_____

Dr. Mari Dias is a nationally board-certified counselor, holds a Fellow in Thanatology and is certified in both grief counseling and complicated grief. Dias is a Certified death doula, and has a Certificate in Psychological Autopsy.

She is Professor of Clinical Mental Health, Master of Science program, Johnson & Wales University. Dias is the director of GracePointe Grief Center, in North Kingstown, RI. For more information, go to: http://gracepointegrief.com/ .

She is the author of GriefSpeak, vol. 1, Stories of Loss

A prayer for Sebastian.

A vicarious hug to you for the work you continue to do.

Peace and blessings from on high.