Search Posts

Recent Posts

- We Cook! Mill’s Tavern’s Heirloom Tomato Caprese with Basil Gel and Balsamic Drizzle June 26, 2025

- CODAC a one-stop center for whole person care – G. Wayne Miller, Ocean State Stories June 26, 2025

- To Do in RI: Collector-Con Providence 2025 – Meet Tony Jones! June 26, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather Forecast for June 26, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 26, 2025

- RI Veterans: Did you know? 26.06.25 (Golf – Early Retirement – Events – Benefits) – John A. Cianci June 26, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

America’s Crisis of Classicism – David Brussat

by David Brussat, Architecture Here and There, contributing writer

Photo, top: View toward Mall from Constitution Avenue, in Washington, D.C. (twenty20.com)

Below is a long guest post written by Scottish architecture critic David Black, who lives in Edinburgh. Written in light of controversies in the United States over former President Trump’s effort to align the styles of federal architecture with American principles and tastes, Black’s essay looks with a gimlet eye at the cases for classicism and modernism. His essay is by far the longest post, by me or by a guest, on Architecture Here and There, and I can assure you that it is worth every minute.

***

America’s Crisis of Classicism: A Philosophical Conundrum?

David J Black

President Biden’s sacking of a soft-spoken, bespectacled academic from the US Commission of Fine Arts represented an interesting moment in the story of American architecture in that it invited us to consider whether, in terms of its once secure and comforting national identity, the USA, architecturally speaking, might be falling out of love with itself.

In this quasi-ideological comic-book urban showdown of smoke, mirrors, generous helpings of prejudice, and the spectre of Donald J Trump, it would appear that in the world of architectural politics, or political architecture, a surprising number of highly-placed people seem congenitally incapable of telling their left from their right. Viewed, in the case of this writer, from the classical city of Edinburgh, Scotland, this bad-tempered squabble seems as puzzling as it is exotic.

An explanation: Dr Justin Shubow, a former Yale philosophy instructor, has long been president of the National Civic Art Society, which champions ‘classical and humanist’ architecture in the public realm. In 2018 he was appointed to the US Commission of Fine Arts, which was established in Congress in 1910 to ‘guide the architectural development of Washington DC’ among other things.

If this makes him sound like some sort of nostalgia-infused elitist, it should be borne in mind that opinion polls suggest the majority of Americans support him on matters of federal public architecture, regardless of age, gender, education, income, race, ethnicity, religion or political party. He speaks, in effect, for most of the masses.

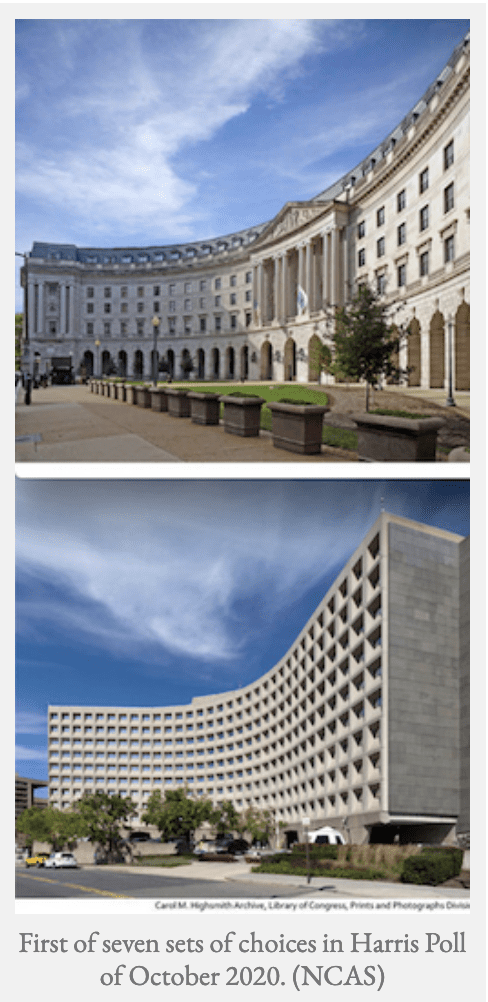

In 2020, Harris pollsters showed 2,039 people images of (a) Marcel Breuer’s 1970s brutalist Hubert Humphrey building and (b) John Russell Pope’s quintessentially classical 1930s National Archives building, both in Washington DC, and asked which they preferred – the one that looked like a hybrid of the House of the Soviets in Kaliningrad and a flyblown 1950s suburban tax office, or the one that looked like a Greek temple on Mount Parnassus.

The surprise was that while 83 percent supported the latter, in the end it would be the 17 percent which, thanks to the latest presidential intervention, would win the style wars. The tail now wags the dog.

While it is doubtful whether any metric exists which can reliably show where an architectural style sits on the political spectrum, this particular spat appears to have supposedly left-of-centre Democrats embracing the architectural tastes of Ayn Rand, an ideologue so far to the right that she would make most Republicans blush. Her credo, as expressed in her near unreadable 1943 book The Fountainhead, was that modern architecture was about ‘the right of the ego’, while anything traditional, like classicism, was collectivist communitarian dross which should be eliminated.

Rand’s hero was ‘visionary’ Howard Roark, whose buildings (at least in the 1949 movie) were lift-offs from the worst period of European international modernism. The fact that he raped a lady (well, he was a superhero after all) while fixing her fireplace was an apposite analogy for his approach to urban development: bully everyone, trash everything, build anew, and make heaps of money.

Whether or not Rand’s architect hero was based on Frank Lloyd Wright is a moot point, but there is no doubt that the model for the book’s villain, Ellsworth Toohey, was Harold Laski, chairman of the UK Labour Party. Rand dedicated much of her time to helping Senator McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee. Anything with the least hint of liberalism, like Frank Capra’s movie It’s a Wonderful Life, was a target for her venom. An implacable opponent of traditional architecture, she would certainly have applauded President Biden’s defenestration of Dr Shubow.

To grasp what this strange controversy over classicism is all about, it helps to scroll back to the origins of the newly independent republic’s ‘national style’. For Thomas Jefferson, writing to the architect Henry Latrobe in 1812, the purpose of an American national style in architecture was not complicated. The Capitol building, for example, was to be ‘the first temple dedicated to the sovereignty of the people; embellishing with Athenian taste the course of a nation looking far beyond the range of Athenian destinies.’ It’s unlikely the sort of ‘people’ he had in mind were the ones who swarmed all over it on January 6, 2021.

America’s national style, even in its earliest years, had a certain viscosity. Federalists favoured the ‘Adamesque’ grammar of such architects as William Thornton, who planned the Capitol building, and Charles Bulfinch, whose father had studied medicine in Edinburgh just as it was extending beyond its medieval girdle. He lodged with University principal William Robertson, cousin and close friend of the Adam brothers, the world’s first progenitors of an ‘international style’. Presidents like Jefferson and Monroe added a modicum of Neo-Greek monumentality and Napoleonic chic to the feast, but every bit of it was solid, scholarly enlightenment classicism.

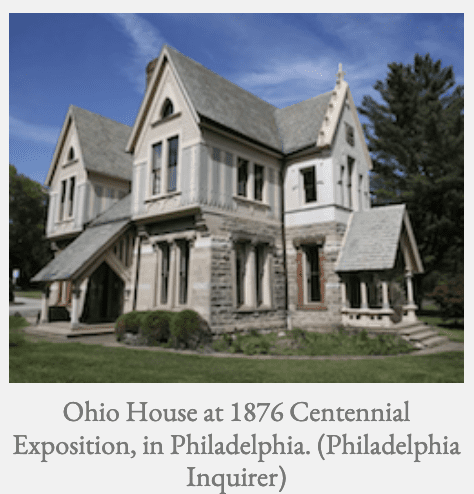

As the 19th century progressed there were departures into the realms of Collegiate and Ecclesiastical Gothic and flourishes of Parisian Beaux-Arts. The guardians of the flame were writers like Edith Wharton and architectural practices like McKim, Mead and White. ‘Brand America’ was reinforced in 1876 during the Philadelphia Centennial celebrations, though the style-wars bifurcation into the Classical and the Romantic brought variations like the homely American Gothic revival (if classically symmetrical) ‘Ohio House’ in Philadelphia’s Fairmont Park.

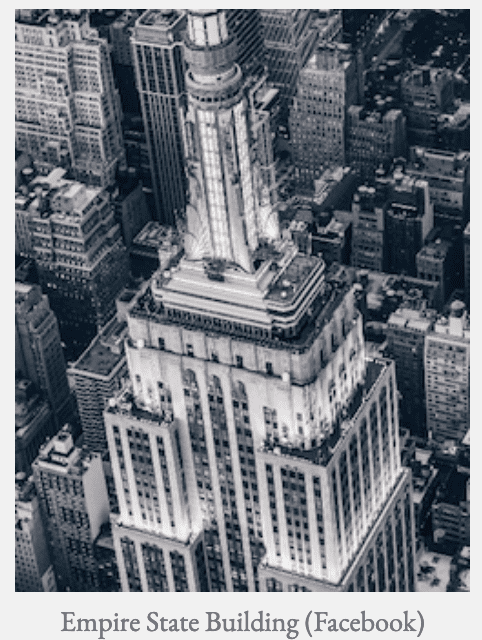

Even New York’s first skyscrapers evoked the wholesome ethos of tradition in a new, distinctly American, symbiotic style. Henry Hardenbergh’s buildings might be twenty floors high, yet they exulted in the grammar of traditionalism. The Beaux-Arts origins of the Empire State Building are unmistakable, and possibly unavoidable, since its designer, William F Lamb, the son of a Glasgow-born Brooklyn contractor, gained his Beaux-Arts diploma in Paris before going on to work for Carrere and Hastings, architects of the New York Public Library and the Forbes Magazine Building.

The Empire State Building is closer in spirit to these precedents than anything that urban disruptors Le Corbusier, Richard Neutra, or Mies van der Rohe ever concocted. Likewise, to call Beaux-Arts alumnus Daniel Burnham’s Flatiron Building, in New York, an example of modernism makes little sense. The same could be said for Cass Gilbert’s Woolworth Building in Lower Manhattan, and Louis Sullivan’s Carson, Pirie, Scott Building in Chicago. These were all modern buildings incorporating novel technologies such as the Otis lift, but they were certainly not seeking to be modernist.

Much the same could be said of the tastefully detailed high-rise apartment blocks built for brothers Leo and Alexander Bing in Upper Manhattan and Greenwich Village – their block at 1000 Park Avenue even has effigies of both brothers in medieval dress flanking its gothic entrance. Alexander Bing, in particular, had a social conscience. He founded and promoted the City Housing Corporation which planned the ‘Garden City’ style Sunnyside Gardens community in Queens.

Bing & Bing also built the 1926 Drake Hotel, in New York, patronised by virtually every star in the firmament from Lillian Gish to The Who until its 2007 demolition. Its replacement was the world’s tallest residential building, Rafael Vinoly’s 432 Park Avenue, damned by Fortune Magazine’s Joshua Brown as ‘the house that inequality built’ and The New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik as the tallest, ugliest, and among the most expensive private residences in the city’s history – the Oligarch’s Erection, as it should be known – a catchment for the rich from which to look down on everyone else, it is hard not to feel that the civic virtues of commonality have been betrayed.

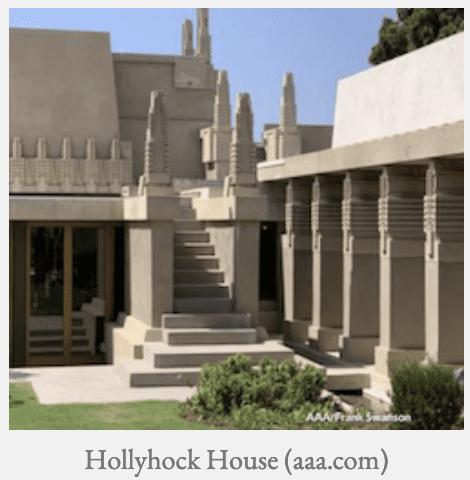

The early buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright, too, while they might be quirky, evoke a sense of tradition rather than the streamlined futurism favoured by Corbusian fundamentalists. His 1919 Hollyhock House in Los Angeles, for example, is curiously reminiscent of an Indian railway station in the heyday of the British Raj. It also served as the perfect location for the 1989 film Cannibal Women in the Avocado Jungle of Death. Wright, while included in the 1932 MOMA exhibition of international modernism, nonetheless derided it as ‘the miscarriage of the machine age’ and would later join forces with architectural writer Elizabeth Gordon when she denounced international modernism as an expression of doctrinaire totalitarianism.

To equate Frank Lloyd Wright with international modernism is almost as absurd as Sir Nicholas Pevsner’s attempt to claim William Morris as a pioneer of British modernism, dismissed by art historian Robin Middleton as ‘a piece of propaganda for the establishment, in particular, of the modern movement in England.’ Wright’s only skyscraper, the 1956 Price Tower in Oklahoma, was a 19-floor baby compared to Chicago’s 109-floor Sears Tower, though that didn’t stop him dreaming up oddities like his (mercifully unbuilt) ‘Automobile Objective’ on Maryland’s Sugarloaf Mountain.

America, with a few exceptions, maintained a healthy urban wariness of the life-denying excesses of European minimalist modernism until after World War II, but it was just too lucrative to resist for developers eyeing up profits, empire-building institutional academics, or city councils in search of mass housing. The great exemplar was the 1954 Pruitt-Igoe housing project in St Louis. This became famous not so much for its architectural scariness as for its starring role in Godfrey Reggio’s 1982 film Koyaanisqatsi, in which it was dramatically blown up to the music of Philip Glass.

While it would be only fair to point out that these 33 blocks of 11-storey housing for the poor were a socially prescriptive failure as much as a design one, Pruitt-Igoe’s armageddon was craftily co-opted by architectural theorist Charles Jencks, who conveniently hailed this televised moment as the ‘death of modernism’ (3:32 p.m. on July 15, 1972, though he got the date wrong) at which point ‘Post-Modernism’, its funky dressing-up box alternative, came into being.

It wasn’t quite the end of astringent Corbusianism, however, since Pruitt-Igoe’s architect Minoru Yamasaki was yet to sign off his Lower Manhattan twin towers, whose end would also be dramatically televised in September 2001 in rather more spine-chilling circumstances.

‘What, then, is this new man, the American’ asked the French immigrant Michel-Guillaume de Crevecoeur in the years leading up to the revolution. A similar question could be posed with regard to the genesis of that distinctly American brand of classical architecture which the Biden administration would, it seems, prefer to turn its back on.

Does this ill-conceived appetite for dog-whistle cultural nihilism suggest that America has suddenly become embarrassed about being American? Why is the architectural soul of this once confident nation so troubled?

Conflating the Zeitgeist

Civic America’s current anti-classical frenzy began with a leaked 2020 report about a proposed presidential order to re-instate classicism as the preferred architectural grammar of the Federal City. That the signatory in this case was Donald Trump was, predictably, the kiss of death for the urban classical ideal, as well as a call to arms for hubristic architectural modernists, their profit-seeking property-investor backers, and certain self-regarding archi-scribes and pharisees of the press.

The anti-classicism cause was much amplified under the headline “MAGA War on Architectural Diversity Weaponizes Greek Columns,” by New York Times architecture correspondent Michael Kimmelman. This was probably as close to endorsing the spirit of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead as that once liberal newspaper has ever got; but just who, we might ask, was doing the weaponizing?

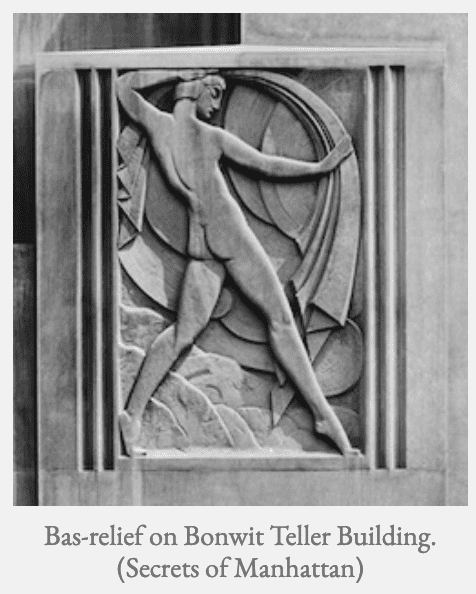

That the executive order would eventually be signed by Donald Trump caused much angst. One almost sympathises, for it was he who, in 1980, promised to give the Metropolitan Museum important bas-reliefs from the Fifth Avenue Bonwit Teller building before having them smashed to pieces in a fit of power-crazed anti-heritage pique. The Bonwit Teller store would make way for not-so-classical Trump Tower in mirror-glass-box style by uncompromising ‘flash ’n’ cash’ modernist Der Scutt.

It is of course one of history’s great ironies (pace Henry Kissinger’s Nobel Peace Prize) that an aesthetically challenged developer who somehow became president should seemingly end up endorsing the aims of the 1902 McMillan Commission’s ‘City Beautiful’ proposals. Moreover, for some, this particular president’s journey to enlightenment had rather dark beginnings.

In 2017 he became embroiled in controversy by offering support to those who were out to preserve the country’s heritage of Confederate statues. The fact that the old Confederate heroes in question had had as their objective the destruction of the United States per se was glossed over, likewise the fact that the destruction of public works of art by any faction, left or right, doesn’t actually contribute to a deeper understanding of a nation’s history.

This point was sadly overlooked by speaker Nancy Pelosi when she greeted the razing of the marble statue of Christopher Columbus in her home town of Baltimore with the verbal shrug-off ‘People will do what people will do.’ Perhaps so, but this is a logic which ultimately endorses the Taliban’s destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas, or the damage to ancient Palmyra by ISIS.

By July the 4th 2020, Mr Trump was addressing the nation from Mount Rushmore as guardian of the nation’s cultural patrimony. It could, perhaps, be argued that this was akin to giving King Herod a babysitting concession; after all, one of the mountain effigies was Abraham Lincoln, slain at the behest of a Confederate cause which Mr Trump had acknowledged in his championing of secessionist monuments in the south; but in an election year it was soundbites, rather than sound reasoning, which made the bulletins.

In any event it is not helpful to conflate the controversy over statues with the altogether different matter of whether the development of Washington’s Mall and other federal sites should be regulated in accordance with the principles of the ‘City Beautiful’ movement, or whether the introduction of ‘disruptor’ buildings by celebrity modernist architecture will be a benefit to the zeitgeist of some imagined ‘New America.’ It is even less helpful to consider the issue through the lens of one individual’s reputation.

Reactions to the executive order ‘Promoting Beautiful Federal Civic Architecture,’ which finally came into force in December 2020, ranged from the outraged to the supportive. Critic Martin Pedersen stated that ‘Modernism as a sort of style religion has lost the moral high ground (if it ever truly possessed it) due to its role as the face of global capitalism and income inequality,’ adding, as a prescient afterthought ‘So, if your goal is influencing the hearts and minds of the young – then hitching your fate to the Trump brand is likely to have the opposite effect.’ Spot on, Mr Pedersen.

On the other hand Martin Filler, author of Makers of Modern Architecture, launched a tirade against classicism in The New York Review of Books, noting ‘Hitler’s insistence that all public buildings in the Third Reich hew to the classical tradition,’ neatly establishing a link between an architectural style and a genocidal tyrant which, by dint of some perverse logic, toxifies the style.

In words Filler attributed to some unidentified ‘left-leaning’ architectural lobby, classicism was ‘a blatant attempt to leverage aesthetics in the service of white supremacy.’ Thus a capricious supposition which would, in the interests of consistency, also conclude that since Hitler was a vegetarian, then vegetarianism itself can only be a social evil, somehow entered the lists.

Invective became the order of the day. Reinhold Martin, professor of architecture and media at Columbia University, railed against ‘the project to make America classical again – the latest episode in a more organized anti-democratic performance – with neoclassicism as its architectural standard bearer and Black Lives Matter as its political foil, the avowed humanism of the National Civic Art Society is nothing but an attack on the state’s social-democratic redistributive function.’

In a less vindictive if equally impetuous outburst of anti-classical fervour in Yale’s quarterly The Politic, student economist Jennifer Wu began her revanchist plea for a more diversified architectural modernism and a wholesale abandonment of classicism with something which isn’t even a building – Maya Lin’s 1982 Vietnam War Memorial, just off the National Mall.

In marking this American tragedy, the choice of an architect of South East Asian descent was a gesture of reconciliation. Lin approached her project as a wound in need of healing, sensitively placing her granite memorial wall below ground level precisely because she didn’t want to compete with the capital’s ‘national style’, particularly that of the nearby Lincoln Memorial. It was a stroke of genius. Those of us who have visited the memorial, aware of grieving relatives running their fingers over the inscribed names of the fallen, are left in no doubt that this sacred site is much more evocative than any big-statement signature building could ever have been.

Ms Wu doesn’t get this, however, as she bemoans the National Mall’s lack of modernism, though she cites a few examples like the Hirshhorn Museum of contemporary art by SOM’s Gordon Bunshaft, a forbidding gun emplacement not quite ameliorated by its four-acre sculpture garden. Otherwise she twists a knife into the much vilified Dr Shubow, whose appointment she deems ‘the [Trump] White House’s first step towards complete control over the aesthetics of federal buildings.’

This rather misses the point that it was an executive order of 1962 which had thrown out the McMillan Commission’s assumption in favour of new federal buildings’ being more or less harmonious with Washington DC’s established classical grammar. Wasn’t the 1962 decision also a bid to exert control?

Likewise, President Biden’s abandonment of the sort of federal classicism which four out of five Americans prefer is itself a gesture of control at the behest of others. This was a response, it appears, to a report from a task force established by Washington’s current mayor, Muriel Bowser, to ‘remove, relocate, or contextualise’ landmarks such as the Jefferson Memorial, and to focus on ‘key disqualifying histories, such as participation in slavery, systemic racism, mistreatment of, or actions that suppressed equality for, persons of color, women, and LGBTQ communities.’

Mr Biden’s order was essentially a dirigiste reaffirmation of (future) senator Daniel Moynihan’s 1962 Guiding Principles for Federal Architecture promoting ‘the choice of designs that embody the finest contemporary American architectural thought’. Senator Moynihan was no philistine. He liked to quote Pericles and save several historic buildings, such as Washington’s old Patent Office, now the US National Portrait Gallery. He supported First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy’s campaign to preserve historic Lafayette Square, opposite the White House, and referred to the demolition of New York’s Penn Station as ‘the greatest civic crime’ in that city’s history. His DC office was in the ‘City Beautiful’ Russell Senate Building, and he has, as his everlasting memorial, McKim, Mead and White’s hyper-classical Old Post Office in New York, now ‘The Moynihan Train Hall.’

But this was moonshot America seeking new ‘signifiers’, so he let the modernist cat out of the bag and into the Federal City. How much of ‘the finest contemporary American architectural thought’ emerged is questionable. He would later bemoan the result, stating ‘Twentieth Century America has seen a steady, persistent decline in the visual and emotional power of its public buildings.’

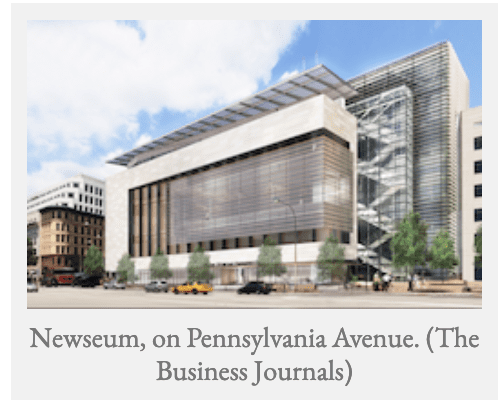

His hope that ‘the finest contemporary architectural thought’ would permeate the federal built future invites us to consider just how truly ‘American’ his Guiding Principles were. To be nit-pickingly didactic, Frank Gehry, whose obtrusive Eisenhower Memorial is a bete noire of Dr Shubow’s, is a Canadian. James Polshek, whose a-contextual ‘Newseum’ building at 555 Pennsylvania Avenue was panned in the New York Times as ‘the latest reason to lament the state of contemporary architecture in Washington DC’, is American born, but was processed through the practice of Chinese born I.M Pei, an ally of Bauhaus disruptors Gropius and Breuer.

Mr Pei himself was singularly favoured in the changing face of Washington DC, albeit he exhibited some coyness in such buildings as his 1978 addition to the National Gallery, built from the same Tennessee stone as Pope’s nearby ‘City Beautiful’ building.

The result eschews the ostentatious gaudiness of his former colleague’s ill-fated Newseum, and may claim, as its principal virtue, a sort of character-deficient inoffensiveness, but this would hardly seem like much cause for celebration.

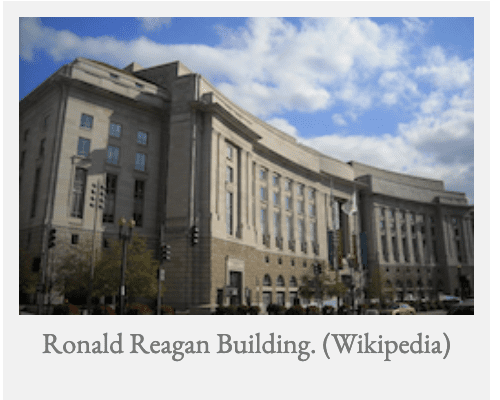

Another DC building from Pei’s office betrays a hesitant withdrawal into pastiche timidity, however overwhelming its scale – at 3.1 million square feet this is the largest federal building after the Pentagon. The Ronald Reagan Building and International Trade Center has been described as ‘faux federal’, and certainly exhibits a kind of dull, ponderous Roman monumentalism. Bedevilled by endless construction and scheduling shenanigans involving Mayor Marion Barry’s office, the Pennsylvania Avenue Development Corp, the General Services Administration, the Office of Management and Budget, and the Federal Triangle Corp, the architect’s fee – already the highest of seven submitted – rose from $26 million to $52 million. Even so, some were relieved that the project didn’t end up with one of the more gauche modernistas, such as Mayne, Holl, Gehry, or Hadid.

It really shouldn’t matter a damn which architect comes from where in the creation of an immigrant nation’s civic identity, especially in the case of a polyglot city like Washington DC, first projected by a Scotsman, George Walker, in The Maryland Journal and Baltimore Advertiser on January 23rd 1789 and laid out in plan form by a French military engineer, Pierre L’Enfant, in 1791, with the help of an African-American surveyor, Benjamin Banneker. The White House, begun in 1792, and loosely based on Dublin’s Leinster House, was designed by Irish Catholic James Hoban, with porticoes by English Moravian Benjamin Latrobe, and built by a Scot, Colen Williamson.

The Capitol building is the work of several architects, American and otherwise, beginning with West Indies born Scots Quaker William Thornton, a polymath who developed a strong interest in architecture while studying medicine at Edinburgh University, when the construction of the neoclassical Georgian New Town was under way. He was succeeded by Latrobe, who had been brought to Thomas Jefferson’s attention by the Scottish marble mason, James Traquair.

America’s classicism, a heterodox distillation of enlightenment ideals, belongs neither to the right nor the left. It was an intellectual and emotional expression of the values of the world’s first constitutional democracy in toto – a nascent, imperfect republic, to be sure; ruled by white male lawyers and landowners who lorded it over disenfranchised women and enslaved black people, certainly. Even so, that ‘great experiment for promoting human happiness’, as George Washington described it, was a marvel in its time, and grew into something remarkable. Why disinvent it?

Those with an urge to de-classicise one of the world’s great planned cities of the 18th century would re-imagine it as – what? Dubai by the Potomac? Hudson Yards redux? A developer’s dystopian Dhaka? And could someone please explain how it is, exactly, that the denigration of its original architectural character and the encouragement of urban disruptor buildings by multi-millionaire architects will be some sort of triumph for an imagined inclusive left, rather than for raw capitalism?

Classicism, Iconoclasm, and the Rise and Fall of the Democratic Intellect

The belief that American classicism begins and ends with the great buildings of state, like the Capitol, the Supreme Court, and the legislatures of, say, Austin, Providence, and Virginia, conceals the fact that, on the whole, its first utterances were the domestic products of private patronage.

When Bishop Berkeley arrived in Narragansett Bay in 1729 I suspect it was his fellow immigrant, the Scottish artist and occasional architect John Smibert, who designed a new neoclassical doorcase for his plain, if comfortable, farmhouse, Whitehall. Smibert went on to design Boston’s Faneuil Hall and Holden Chapel in Harvard Yard, though whether this justifies the title ‘the father of American architecture’, as claimed on a painted sign in Boston’s South Churchyard, is perhaps debatable.

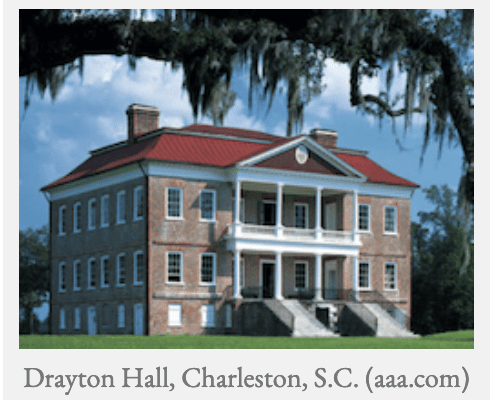

It is possible, too, that America’s oldest Palladian mansion, Drayton Hall, in South Carolina, was designed by Scot George Haig, who arrived in Charleston in 1733, aged 21, to become, in time, its deputy surveyor general. He already had links in the town. His father’s name (spelt Haigs) appears in the 1729 Charleston St Andrews Society roll book. The diamond shape in an upper-floor fireplace at Drayton which features in Haig family heraldry may also offer a clue. However, recent dating of the roof timbers suggests a construction period shortly after his death in 1748, though his plan may well have been completed by another hand, such as that of the wright Robert Deans.

The attribution remains speculative, though Haig, known as a ‘very prolific surveyor, mainly in the townships of Amelia, Saxe-Gotha, and Orangeburg’ is certainly a well-qualified candidate to be Drayton’s putative designer/builder, even though tradition favours John Drayton himself. Haig boarded at the home of a relative, Lilias Skene Haig, whose father-in-law, William Haig, had been one of the earliest surveyors of an area of land by the Delaware River which would later become the city of Philadelphia. Place-making was very much in this family’s DNA.

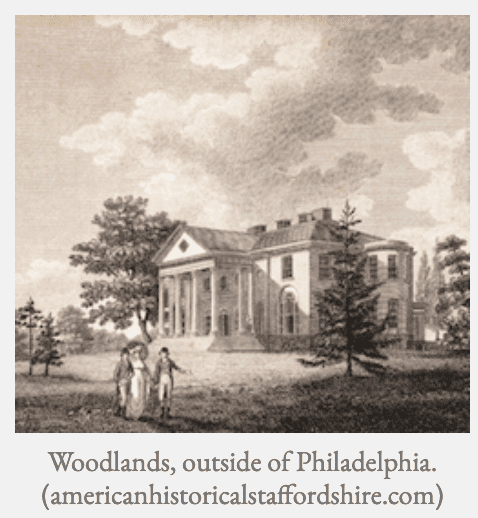

Philadelphia, as it happens, still has one of the most ‘Adamesque’ mansions in the USA. Originally home to lawyer Andrew Hamilton (whose successful 1735 defence of the printer and publisher John Peter Zenger was to become a precedent for the constitutional right to free speech), in the hands of his grandson William the enlarged mansion, Woodlands, would become ‘the first fully realised Federal architecture in North America’.

Hamilton almost certainly met one or both of the Adam brothers during his 1780s visit to Europe and, like them, he was a subscriber to the influential “Treatise on the Five Orders of Architecture” by their head draftsman, George Richardson. The tempting thought that the brothers might have had some significant input into the building’s design should probably be resisted. Even so, its elements are clearly derived from their ‘corrected style’, so no one can deny that Woodlands is just possibly the only building in America designed by the brothers Adam, which is quite a thought!

The most prominent classical building in Philadelphia, however, is undoubtedly the neo-Greek Museum and Art Gallery on Fairmount Hill, just outside the city centre. With this, the banal thesis that architectural classicism is ‘a blatant attempt to leverage aesthetics in the service of white supremacy’ as trumpeted by Martin Filler falls to pieces, since the building’s exterior, from its famous steps to its polychrome pediment, was designed by the African-American architect Julian Abele, one of America’s most sensitive exponents of neoclassicism.

Despite a $233 million internal makeover by Frank Gehry, Abele’s exterior retains its power and dignity as one of the great neoclassical urban masterworks of the United States, while it confounds the ill-informed prejudices of those who bizarrely insist that classicism, as the favored national style, is the architecture of a racist right.

A look at the facts behind the sloganizing might, on balance, tend to favour other conclusions. In contrast to the African-American classicist Abele, the major proselytiser of modernism in twentieth century America was the architect Philips Johnson, whose activities included attendance at National Socialist rallies in Nuremberg and Potsdam, avidly supporting Adolf Hitler (whom he found ‘spellbinding’), anti-semitic and anti-black outbursts during a foray into journalism in which he was paid by the Nazi government to cover the invasion of Poland, and hosting meetings of American Nazis in his apartment. He also wrote rave reviews of Mein Kampf for the pro-Fascist quarterly The Examiner and attended Nazi rallies in Madison Square Garden.

It may also be noted in passing that New York’s most prominent classical building at one time was the same Pennsylvania Station whose loss Daniel Moynihan described as the greatest civic crime in the city’s history. As with Julian Abele’s Philadelphia masterpiece, to characterise McKim, Mead and White’s railway-age reinterpretation of ancient Rome’s Bath’s of Caracalla as a symbol of white supremacy would be a mistake. The Emperor Caracalla, after all, was half Syrian and half Libyan.

If the denigration of classicism is not informed by scholarship, what, then, is its true underlying dynamic? Could it be an example of ‘poacher’s cloak’ politics in action? This is the technique whereby one particular interest group – say celebrity architects and their developer backers – seeks to sow confusion by exploiting the anger of another for its own ends. Some see it as an extension of statue-felling, which has long moved on from the de-plinthing of Robert E Lee and his Confederate henchmen, or even the morally deficient Christopher Columbus, to a comprehensive drive to sweep away all statuary, it would seem – including effigies of the emancipators Lincoln and Grant.

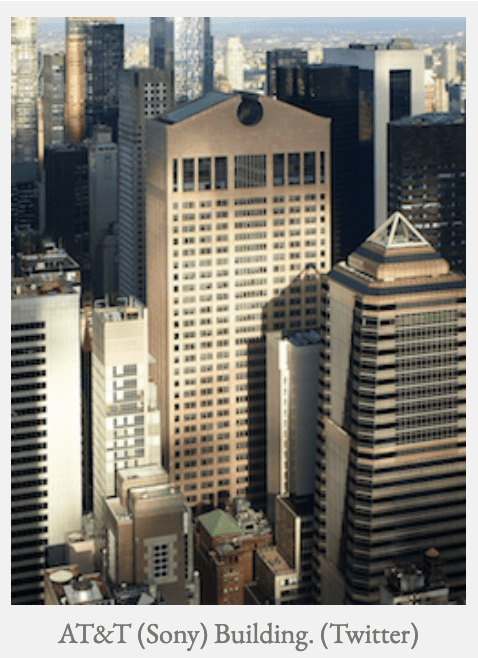

Anti-classicism is, at root, an iconoclastic spasm. Philip Johnson would probably have understood this perfectly. He combined a Houdini-like ability to escape his fascist past with the consummate skills of a propagandist and the suave persuasiveness of a wealthy Madison Avenue marketing guru. When it seemed possible that the FBI might arrest him as an enemy agent, he enlisted in the US Army. As a modernist he hedged his bets, topping off his AT&T headquarters building with a faintly classical Chippendale pediment (‘The Seagram Tower with ears’ – Village Voice) and marching alongside Jane Jacobs and Jacqueline Kennedy to oppose the demolition of Pennsylvania Station.

As curator of the 1932 MOMA exhibition on international modernism, Johnson, the quintessential elitist, like MOMA director Alfred H Barr, had scant interest in social architecture or utopian housing, though the urban theorist Lewis Mumford was grudgingly given limited space in an isolated room for an exhibition of planning and housing, and even Alexander Bing was granted a token look in. Otherwise the catalogue was largely a mix of ‘starchitect’ hagiographies of such Nietzschean Ubermensch (no women, and certainly no non-white ethnicities) as Le Corbusier, Wright and Oud, whose virtuous profiles were provided by Henry Russell Hitchcock, though Johnson reserved the Mies van der Rohe puff for himself.

Patrons of and contributors to the exhibition included Jacobo Fitz-James Stuart y Falco, 17th Duke of Alva (or Alba), 10th Duke of Berwick and pretender to the throne of Scotland, who would later become General Franco’s representative in Britain, and a supplier of useful intelligence to the Third Reich, via Madrid.

At the other end of the political spectrum was a close friend and patron of Mies van der Rohe, Marxist-Leninist Eduard Fuchs, who had been appointed by Lenin to organise prisoner exchanges after World War 1, was a member of Berlin’s Bolshevik Comintern, and had commissioned Mies to design a monument to the communist martyrs Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht.

Others included Baroness Helena von Nostitz-Hindenburg who, the following year, would be one of nine influential German women to sign the Oath of Allegiance to Adolf Hitler; and Georg von Schnitzler, head of chemical giant I.G.Farben, manufacturers of Zyklon B gas, who would be sentenced for war crimes in 1946. All in all, totalitarianism, left and right, was well represented.

Given this ambivalent pedigree, it is surely paradoxical that the generally justifiable sensitivities of Black Lives Matter activism have somehow been press-ganged into the modernist cause. Even if Philip Johnson and Ayn Rand had never existed, one might wonder how yet more expensive, big-ticket city centre projects by rich modern ‘disruptor’ architects and profit-hungry developers would actually benefit ordinary communities, black or white. Could it not be that the average citizen needs less vanity-fueled bombastic corporate and state modernism, not more?

But we are urged to forget all that. The repeated refrain must be that classical architecture is damned on the flimsy pretext of guilt by association, and those who defend it must can only be right-wing reactionaries, particularly since their cause was embraced by Donald Trump. Look a little further into this and the theory doesn’t quite hold. In fact, it’s close to being the opposite of the truth.

I don’t know anything about the private political beliefs of those serving on the now reshuffled US arts commission, and don’t particularly care, since their function was to promote the stewardship of federal architecture – an area best left unpoliticised. I have, as it happens, met two of the rejected commissioners, one being Dr Shubow, who spoke at an urbanism conference in Charleston, South Carolina. I recall, above all, his unbridled admiration for Franklin D Roosevelt, a confirmed classicist and New Deal liberal who had his private home, Springwood, remodelled as a Georgian mansion.

Indeed, I discovered some time after the event that Dr Shubow had once been editor of a left-progressive newspaper, Forward, whose original 1912 Beaux-Arts New York building is perhaps the only one in America adorned with bas-relief effigies of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels!

In 2015 I met Dr Shubow’s fellow commissioner Rodney Cook at a planning event in Havana, a few months prior to President Obama’s visit, when there was much interest in the restoration of Cuba’s stunning, if crumbling, built heritage. I hadn’t a clue what Mr Cook’s private political views were, or even if he had any. What I soon discovered, however, was that he was a man of outstanding erudition who has been pro-actively engaged in restoration projects throughout the world.

I was later informed by an Atlanta friend that Mr Cook’s father had been a respected Georgia state representative and friend of Martin Luther King senior. A gang of racists had burnt a Ku Klux Klan cross into the lawn of the Cook family home after he had advocated desegregation in housing. At Mr Cook senior’s funeral in 2013 the eulogy was given by civil-rights leader Andrew Young. Somehow this back story doesn’t quite chime with shallow tropes about classicism and white supremacy.

Apart from that, there’s the matter the effects of endless urban construction on climate change, given that a startling 38 percent of the world’s CO2 emissions in 2020 were produced by the global building industry. Better, by far, to restore and improve existing buildings, or build new ones of local materials in a local style, than to raise yet more versions of the Rafael Vinoly-designed and developer Lendlease-built Oligarch’s Erection at 432 Park Avenue, with its two-foot sway, vertical floods, and walls which reportedly creak like the wooden hull of The Mayflower, which is presumably not the sort of American dream its overseas billionaire purchasers were buying into.

The pedigree of the ‘modernism’ of buildings like 432 Park Tower dates back around 90 years, when Philip Johnson and his collaborators sought to persuade the public that it was the architecture of tomorrow. His skills as a propagandist were utilised when he launched the international modernist exhibition at MOMA which was little more than a drive to import the minimalism of his European associates Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe into America – the latter, incidentally, being not averse to signing off his letters ‘Heil Hitler’ when pitching for work in Germany.

Neither this, Rand’s loathing of traditional architecture, nor Mussolini’s enthusiasm for a glass and steel ‘Casa del Fascio’ offers proof that modernism belongs to the right. There were also left-wing advocates for Corbusianism. It makes more sense to assume that a traditional style like classicism is not the direct outcome of any specifically political ideology. A simple fact which cannot be doubted, however, is that most modernism, and its postmodern alter ego, is elitist, a point well made by Tom Wolfe in his denunciation of the modern movement in America, From Bauhaus to Our House, in which he impishly asks, ‘Has there ever been another place on earth where so many people of wealth and power have paid for and put up with so much architecture they detested.’

An equally acerbic attack was The Architecture of the Absurd: How ‘Genius’ Disfigured a Practical Art by John Silber, an outspoken academic who was, successively, president and chancellor of Boston University, and a one-time Democratic candidate for Massachusetts governor. The Texas-born son of an architect, John Silber takes no prisoners when it comes to criticising the mesmeric hold rich celebrity architects such as Frank Gehry, Daniel Libeskind, and Stephen Holl have on the cultural and educational elites. Silber rails against the ‘theoryspeak’ (a word borrowed from Wolfe) of architects who talk ‘aesthetic and philosophic rubbish’ and, more importantly, asks why their clients were ‘impressed and even intimidated by it.’ By all accounts Mr Silber could be a difficult man, but anyone who openly opposed capital punishment in Texas and was a lifelong Democrat can hardly be characterised as a right-winger simply because he thought modernism was a bit of a fraud.

Classicism: The First International Style, and an Expression of the Democratic Will.

Some might doubt whether this author is really entitled to have a view on the subject of the threat to American classicism. He writes as a Scot who has spent time in the USA but belongs to a city – Edinburgh – which was the result of the progressive precepts of Europe’s 18th century philosophical enlightenment.

Such debates about the way we treat our historic cities are not confined to the USA. Classicism belongs to the world. Its finest expressions can be found not only in Washington DC, Paris, Turin, and Munich, but also in St Petersburg, Russia, and Kolkota (Calcutta), India, among other places.

Tragically, in Edinburgh, an American anti-classicist gesture now disfigures one of the world’s finest 18th century planned townscapes, the classical New Town. An investment by major pension investment corporation TIAA of Charlotte, North Carolina, it rejoices in the locally popular name ‘The Golden Turd’. An American friend seriously wonders whether it would have been approved by the Nevada architecture review authorities for the tacky end of Las Vegas Strip.

The truly sad thing about this is that a great deal of architectural classicism is a shared Scottish-American heritage, representing, in each case, a moment of resurgence in the national spirit of both countries. In 1753, with Scotland’s self-esteem at its lowest ebb after the failed Jacobite rebellion, something of a miracle was wrought when the foundation stone of a new Edinburgh ‘Royal Exchange’, funded by public subscription, was laid by John Adam, and the redemptive power of architecture was revealed.

‘Now Scotland’s youth, with better omen born, salute the dawning of a brighter morn – Last of the arts, proud ARCHITECTURE comes, to grace EDINA with majestic domes’ wrote an ebullient John Home, cousin of philosopher David Hume. The classicism, in this case, was a communitarian show of force, a blow against ‘barb’rous chiefs, with iron sceptre swayed’ who had dominated the past. Edinburgh’s classicism was a potent symbol of patriotic assertiveness, the people’s will, the first stirrings of the ‘democratic intellect’, and dreams of a more prosperous future.

Exactly forty years and five days later President George Washington enacted a similar ceremony when he laid the cornerstone of the United States Capitol building. In both cases these achievements were to be followed and amplified by the construction of two great classical cities; Edinburgh New Town, and Washington DC. It goes without saying that the customs and mores of the 18th century were not those of today. In America’s nascent democracy, whatever lip service the founders may have paid to vague ideas of milkwater abolitionism, George Washington and his wife ‘owned’ a total of 317 enslaved people, which is why anyone with a close interest in the founding period should certainly read that ‘necessary corrective’, Frederick Douglass’s What, to the Slave, is the Fourth of July?

The American Revolution, just like Robert Adam’s ‘Kind of Revolution’ in civic architecture, should be viewed as a developing process, not a single event. There is, it goes without saying, no plea-in-mitigation for the crime of slavery, but we should always seek to judge and condemn in context, and should see the continuation of that revolution in Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation proclamation and the 1964 Civil Rights Act, as well as a work in progress at the present time.

As for the politics of architecture, there is an obvious counter-thesis to the contention that America’s classical tradition in architecture is some sort of conspiracy by an imagined white supremacist right. After all, what is corporate modernist architecture but the built fulfilment of the right wing neoliberal doctrines of Chicago School economics? Writing in The New York Times Magazine in 1970, Milton Friedman, the doyen of unfettered free-market capitalism, accused businesses which claimed to have ‘a social conscience’ of ‘preaching pure and unadulterated socialism’.

Today, US corporate capitalism conspicuously embraces the wholesome acronyms ESG and CSR (Environmental, Social, and Governance criteria, and Corporate Social Responsibility) while waxing eloquent about ‘the sustainability agenda’ yet the supreme imperative, far from ‘unadulterated socialism’, remains that of ‘fiduciary duty’ – the maximisation of profits.

Corporate modern architecture uses the same playbook, rhapsodising in seductive poetry while operating in stark bottom-line prose. Starchitects are never poor. With a net worth of $240 million, Britain’s Lord Foster leads the field, though even at just under half that amount Frank Gehry isn’t doing so badly, while Renzo Piano gets by on $20-30 million and Maya Lin is believed to have banked around $10 million. The earlier generation weren’t exactly struggling either. On his death in 1969 Mies van der Rohe was worth around $5 million – perhaps $40 million in today’s money.

Given the power of wealth and the resultant inequalities of arms this is not, of course, a balanced debate. The advantage lies with the forces of iconoclasm and money churn, aided by a plethora of magazines and glossy books that back their cause. They have, overwhelmingly, the press eating at their table and growth-minded politicians providing them with favours. They also exert a powerful influence over the academic establishment, and thus the minds of future generations of architects.

Moreover, modernism’s architectural nihilists denigrate classicism as ‘architectural conservatism’ as represented by the views of, say, the late Sir Roger Scruton, or the Prince of Wales, while playing down the environmental damage for which they themselves bear much responsibility. They hire PR teams to wine and dine press and politicians, and prefer to avoid critical engagement like the 1982 Harvard debate between Peter Eisenman (later the author of an essay entitled “The End of Classicism”) and the architectural humanist Christopher Alexander, which neither participant could be said to have won, since there was absolutely no common ground between them.

How any of this tallies with the belief that a privileged modernist elite will be serving the interests of the progressive left in matters of class or racial diversity is something of a mystery. A much more persuasive argument than anything Messrs Kimmelman, Filler, or Martin, or Ms Wu, have presented us with in their anti-classical diatribes concerns the ‘democratic essence’ of the classical ideal. After all, if more than three-quarters of the public in a Harris poll prefer classicism to those modernist alternatives which are suggested for America’s federal buildings, this surely suggests it is the people’s choice.

Consider, too, that in Mark Gelernter’s History of American Architecture, of the top three neoclassical European buildings that influenced the neo-Greek style in the emerging United States, two were museums (Smirke’s British Museum in London, and Schinkel’s Altes Museum in Berlin) while the third was a school (Thomas Hamilton’s Royal High School, Edinburgh). The core theme of such architecture, in other words, was the cultivation and betterment of all humankind.

This adaptation of the Socratic belief in the value of knowledge harmonised perfectly with both the Scottish enlightenment and the founding ethos of a republic which began the preamble to its 1787 Constitution with the words ‘We the People.’ It is a demographically inclusive sentiment, and it is appropriate that some of the most sublime classical temples of the ‘great American age’ were designed for mass transit, like New York’s Penn Station. For the late historian Vincent Scully, to arrive at the lost original ‘one entered the city like a god, but now’ he lamented ‘one scuttles in like a rat.’

There is much that is absurd in the phobia of classical buildings by a politically naïve lobby which has persuaded itself that traditionalism in architecture is somehow inimical to the interests of a self-appointed progressive and inclusive left and those it purports to represent. Nor should we unquestioningly endorse the views of a gilded press commentariat which, in many cases, is simply cheerleading its rich architect and developer chums, as evidenced by what the writer Alexandra Lange described as Herbert Muschamp’s ‘5,000-word swoon’ over Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Bilbao which, for him, was ‘a re-incarnation of Marilyn Monroe’.

On the other hand this is not an either/or controversy, with two diametrically opposed factions fighting it out for the urban soul of America. Why should it not be possible to exercise an even-handed judgement, cherishing the great classical heritage on the one hand, while welcoming high quality and appropriately located modern architecture on the other? By no means need everything be classical, even in Washington DC, where the very idea of a Museum of the American Indian inevitably leads to a particularly knotty intellectual quandary.

Although, on the initiative of Daniel Moynihan, it spent many years in Cass Gilbert’s Beaux Arts Alexander Hamilton US Custom House building in New York, there was an understandable demand that the culture and history of America’s ‘first people’ should have a presence in the nation’s capital. This came to pass in 2004 when the Smithsonian opened a National Museum of the American Indian on Independence Avenue.

The problem with designing a large institutional building to represent an indigenous people who have, historically, no tradition of large institutional buildings was always going to be challenging, particularly on this site. For obvious reasons, there could be no question of marginalising it on a nearby location, such as Rosslyn or Bethesda, while designing a large building in a classical style, even on the Mall, would have struck a note of cultural dissonance.

On the other hand, is the invention of a bogus new sui generis style suggestive of ‘Indian-ness’ a persuasive alternative? For this writer, there might have been a way to get this right if the original architect, Douglas Cardinal, had developed his computer generated theme of nature, with the building as some sort of rocky outcrop rising out of its wetland setting, but he was sacked, and would dismiss the later post-modernist variation on the theme of Fallingwater as ‘a forgery.’

On the other hand this was possibly an intractable problem with no satisfactory outcome. If that last open ground near the Capitol was not to have a classically harmonious building, then what should it be? Perhaps the best defense of the building as it finally emerged is that in the hands of one of the more outlandish post-modernist disruptor architects it could have been so much worse.

Despite the endlessly discordant note in most modern architecture, it is perfectly possible to praise a building like, say, Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Bilbao, given what it achieved for the economy of a run-down post-industrial city in Spain, while at the same time decrying the banal flippancy of his later ‘toytown’ projects like the 2004 MIT Stata Center, which ended up with the client suing its architect for negligence, leaks, and design failures.

It is certainly unfortunate that Bilbao, whatever its socio-economic (as opposed to aesthetic) merits, would spawn a host of imitators like Liverpool’s stupendously awful waterfront museum, the sprayed-concrete opera house in Taiwan’s third-largest city, Taichung, or the tawdry extension by Michael Lee-Chin Crystal to Toronto’s Royal Ontario Museum. Other horrors are available.

The very idea that this sort of bilious rash of vanity-fueled architecture is, in some mysterious way, an improvement on the established traditional norms of architecture utterly defies logic. Even more extraordinary is the fanciful notion that the values of unfettered modernism are in some sense liberal and inclusive, and thus an antidote to the alleged elitism of such established styles as classicism, the preferred choice of the overwhelming majority of the population.

Traditional architecture belongs neither to the right or the left, and it is time it was de-politicized. The last thing an architectural style should be is a manifesto for an ideological cult, whatever Ayn Rand, Philip Johnson, or their present-day disruptor acolytes would have us believe.

***

To read the full blog, go to: https://architecturehereandthere.com/2021/11/04/a-conundrum-of-architecture/

To read all of Brussat’s article from RINewsToday, go here: https://architecturehereandthere.com

_____

My freelance writing and editing on architecture and others addresses issues of design and culture locally and globally. I am a member of the board of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which bestowed an Arthur Ross Award on me in 2002. I work from Providence, R.I., where I live with my wife Victoria, my son Billy and our cat Gato. If you would like to employ my writing and editing to improve your work, please email me at my consultancy, dbrussat@gmail.com, or call (401) 351-0457 https://architecturehereandthere.com/

_____