Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Real Estate in RI: Benefit St.’s John Mawney House sells for $1.8M – Compass for seller May 27, 2025

- ART! Blue Star Museums offer free summer art visits for military families May 27, 2025

- Judge Frank Caprio to hold book signing at Mt. Pleasant Library – Compassion in the Court May 27, 2025

- Parenting while living with behavioral health challenges – Ocean State Stories May 27, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for May 27, 2025 – Jack Donnelly May 27, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Your face as face mask art

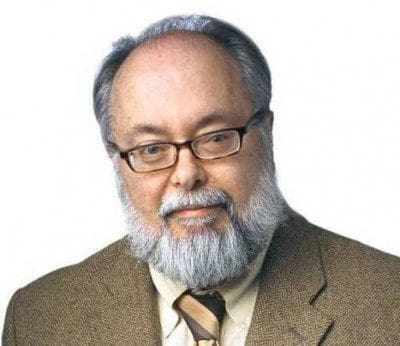

by David Brussat, contributing writer, architecture

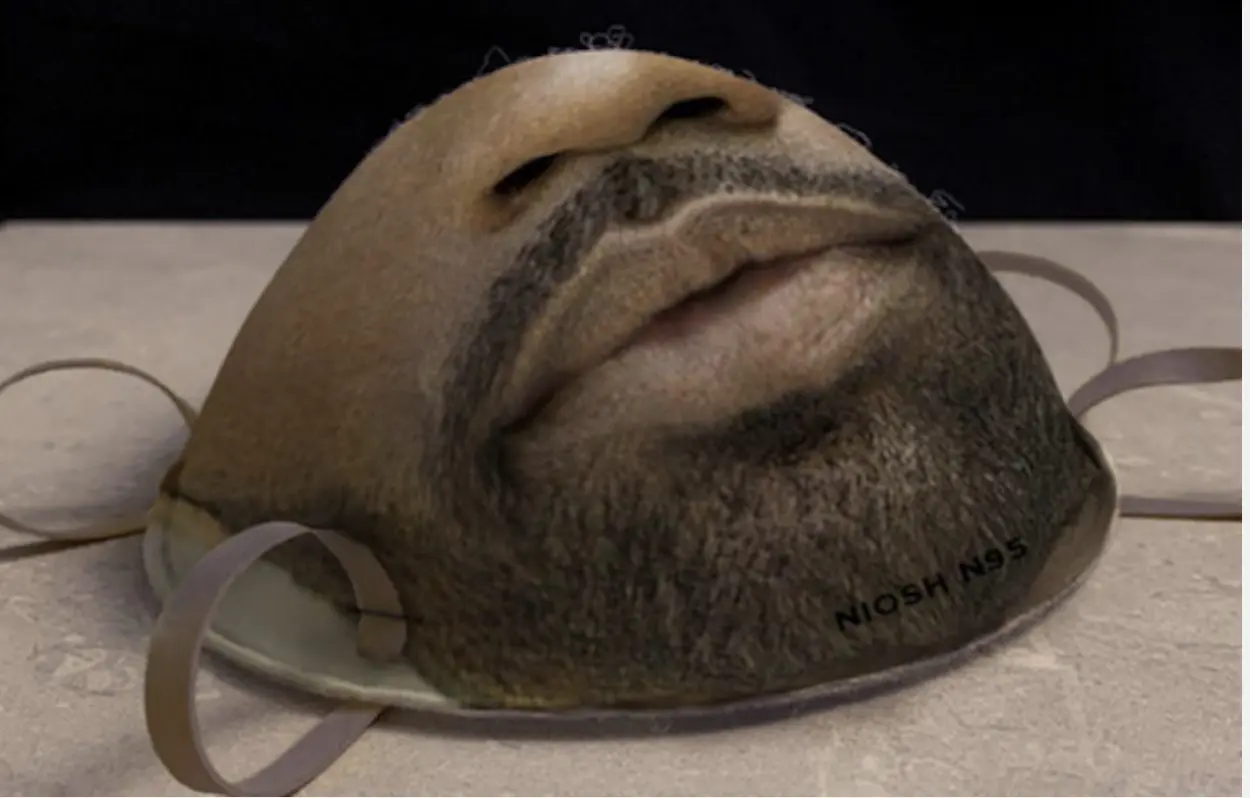

Face mask designed to activate facial-recognition on wearer’s iPhone (Architectural Digest)

Years ago, I urged Providence artists to create murals designed to look like the buildings on which they were painted. A façade with no windows could be painted to look like the rest of the building. Humans could be leaning out the fake windows, or a lower corner of the wall could be painted to look as if it were curling up – as on a downtown mural facing the Providence River.

I thought, for example, that the ugly fourth Howard Building should get a facelift with a mural covering up its modenist fenestration with a classical façade. But nobody was listening, and my building mural campaign fizzled.

Cat face mask. (L.A. Times)

One of the defects of our Covid era is that as cities ramp up the mandate to wear face masks in public, the public grows more and more boring. We can’t see each others’ faces. Not that we can go outside much anyway, but why should face masks make it worse? Instead we see face masks that employ blank, striped, polka dotted, flowered or some type of goofy abstract imagery. Or made to look like the faces of dogs or cats. My own is a bandana cut out of one of my wife’s old nighties. Why shouldn’t our face mask be designed to look like our own face?

It seems that Architectural Digest has just beat me out on this idea with “Design goes viral: Coronavirus face masks that work with face recognition technology.” This article, by Sofya Shatokhina, was published an eternity ago: on March 11. You’d think by now facial face masks would be ubiquitous. But I’ve seen no one wearing masks that look like faces real or fictional, even without the high-tech angle. The article summarizes how to make a face mask whose wearer can log on to an iPhone’s facial recognition program:

The new mask by [Daniel] Baskin displays the lower half of the face, to help create a seamless flow of tech usage. The artist manually translates the 2D images into 3D so that depth sensors react to it, and prints it on the mask.

Facial face mask. (Arch. Digest)

In fact, masks designed for use by specific individuals need not be facial-recognition friendly. The face on the mask could be tweaked to make it more beautiful than the owner’s true face, as if it were an oil portrait of an aristocrat from Edwardian England. The face mask’s mouth and nose would have to fit into the context of the eyes on the actual head of the person, whether it was a regular or improved version. You could sport a beard as a sort of disguise. You could have your usual frown turned upside down, or vice versa – you decide. The possibilities are endless.

Or, if you find that wearing a mask gives you a pleasant sense of traveling incognito, you could make yourself look completely different. You could even abandon the facial stuff altogether (as is the convention for face masks thus far). You could wear the grille of a sports car, a bumper-sticker slogan, the Grand Tetons, the American flag, or even the façade of a building. You could use an existing building, or your own house, or you could have one designed using the eye-tracking computers employed by Massachusetts researcher Ann Sussman to demonstrate why traditional buildings are so beloved compared with modernist ones, which is because their windows and doors tickle our brains’ hard-wired attraction to faces.

Actually, I think I’ll take a mask with my favorite building printed on it: the New York Yacht Club national headquarters, designed by the firm of Warren & Wetmore and completed in 1899. Its front windows look like the elaborate sterns of 18th century naval galleons. Cover me up in that and I’ll be happy.

Click here for full story: https://architecturehereandthere.com/2020/04/22/your-face-as-face-mask-art/comment-page-1/#comment-83289

David Brussat, Architecture Here and There

My freelance writing and editing on architecture and others addresses issues of design and culture locally and globally. I am a member of the board of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which bestowed an Arthur Ross Award on me in 2002. I work from Providence, R.I., where I live with my wife Victoria, my son Billy and our cat Gato. If you would like to employ my writing and editing to improve your work, please email me at my consultancy, [email protected], or call (401) 351-0457 https://architecturehereandthere.com/