Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Senior Agenda Coalition of RI pushes wealth tax to fund programs for older residents – Herb Weiss June 2, 2025

- How will Artificial Intelligence (AI) impact the future of work – Mary T. O’Sullivan June 2, 2025

- Real Estate in RI: Tiverton contemporary for $1.27M June 2, 2025

- Our Networking Pick of the Week: Coffee Hour at Provence Sur Mer, Newport June 2, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 2, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 2, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Women & Infants faces a financial conundrum – Richard Asinof

by Richard Asinof, ConvergenceRI

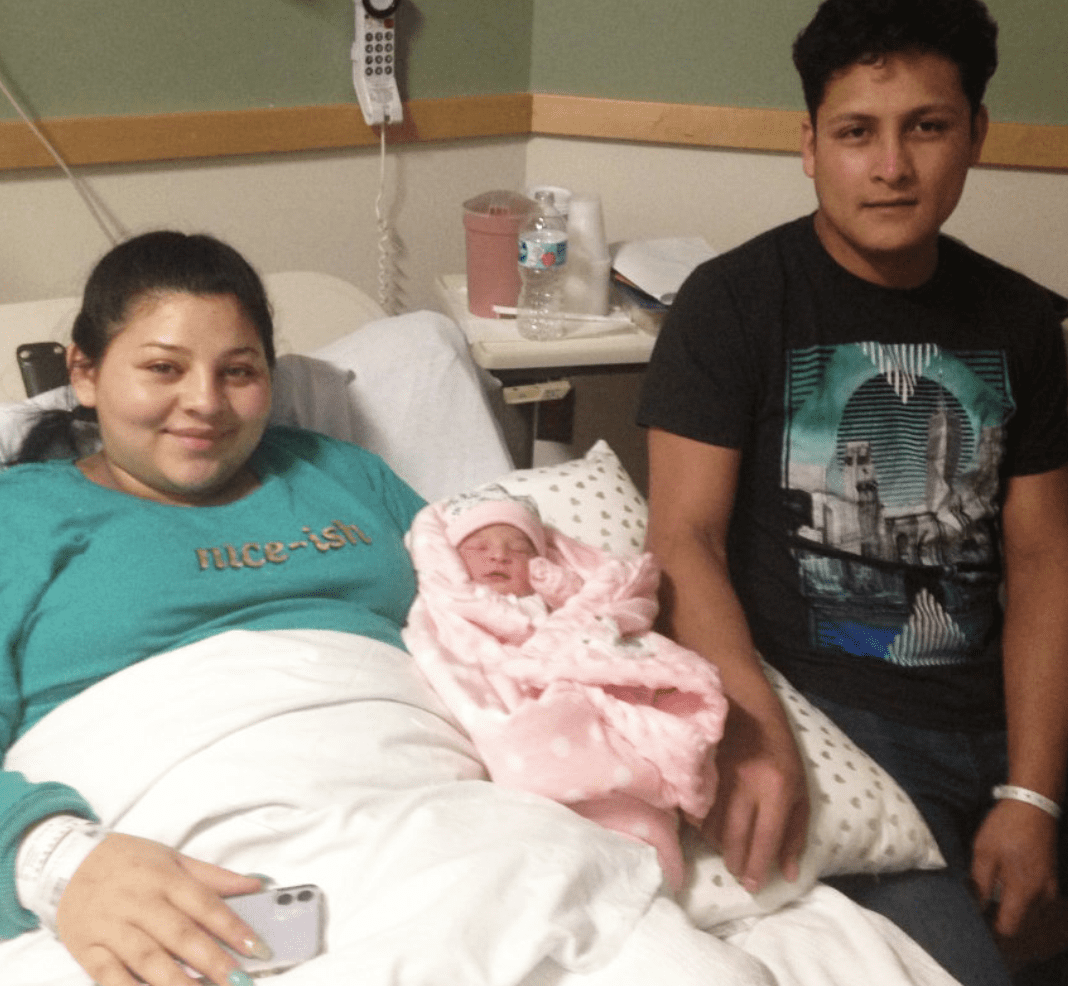

Photo: The first Rhode Island baby born in 2020 to welcome in the new decade at Women and Infants Hospital was Stephania Michelle Escobar Orellana, daughter of Katerin Oviedo Orellana, and Luis Escobar, of Providence, weighing 6 pounds, 5 ounces, their first child. Credit: Richard Asinof

As Rhode Island’s birth rate declines, as innovative prevention programs reduce the number of early births in its NICU, the world-class facility is struggling to break even, despite controlling more than 80 percent of the market share for births.

When it comes to health care delivery in Rhode Island, the engine warning light is blinking on everyone’s dashboard, a worrisome sign for hospitals, nursing homes, community health centers, and patients – and for stressed-out health care workers on the front lines, many of whom have reached their emotional limits.

Translated, the ongoing struggle to contain the contagious Delta variant of COVID-19 is stressing the health care delivery system to the max.

Even as Gov. Dan McKee announced plans last week to turn the lights back on at the Cranston field hospital as a precautionary move, the larger, looming question, perhaps, is this: How will the state find enough doctors, nurses and technicians to staff the facility?

The two largest hospital systems, Care New England and Lifespan, busily moving forward with a proposed merger with Brown University to create a consolidated academic medical enterprise, are finding it difficult to keep their necessary nursing staffing levels intact.

The same is true for many of the state’s nursing homes that are facing new staffing levels mandated by law beginning in January of 2022, in what John E. Gage, the new president and CEO of the Rhode Island Health Care Association, has called an unfunded mandate. In a conversation last week with ConvergenceRI, Gage predicted that the new staffing mandate would result in annual shortfalls in operating expenses in the tens of millions of dollars – resulting in more closures of the 77 nursing homes now operating in Rhode Island.

The good news is that here in Rhode Island, the news is not as dire as it is in other states – including Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas and Arizona, as waves of very sick, unvaccinated patients have been flooding the hospitals, apparent victims of misinformation campaigns around masking and vaccines, misinformation championed by those states’ governors.

Desperate hospitals in those states have been sending up warning flares, as they run out of ICU beds, oxygen supplies, and staffing. And, with Hurricane Ida having reached Category 4 strength before it made landfall in Louisiana on Sunday, the potential for catastrophic public health emergencies in the aftermath of the storm is immense, including the further spread of the COVID-19 contagion – as well as dangerous episodes of air and water contamination, given some 600 sites with toxic chemicals said to be in the hurricane’s path.

The state of Mississippi, for instance, also in harm’s way from Hurricane Ida, has one of the lowest vaccination rates in the country. The state’s Governor, Tate Reeves, recently called the recommended masking guidelines issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the Delta variant “not rational science.”

Reeves said further that religious beliefs were the explanation for why folks in Mississippi and in the mid-South were a little less scared about COVID. “When you believe in eternal life – when you believe that living on earth is but a blip on the screen, then you don’t have to be scared of things.” To quote WPRO’s Steve Klamkin, “Really?”

The health conundrum

Maternal health and the birth of healthy children are one of the cornerstones of any health care delivery system, and here in Rhode Island, Women & Infants Hospital, a division of Care New England, is recognized as one of the nation’s premier specialty hospitals for women and newborns, the 11th largest stand-alone obstetrical service in the U.S., according to the hospital’s website.

Last year, approximately 8,200 babies were delivered at Women & Infants, which serves as the teaching affiliate for Brown University’s medical school, with 32 residents training in Obstetrics. Its nurse midwifery department has been recognized as one of the leading programs in the nation. The hospital also serves as a major research center, and it is the home of a state-of-the-art, 80-bed NICU nursery.

As with many institutions within in the health care delivery system, the coronavirus pandemic has created numerous challenges, particularly in regard to how best to maintain the hospital’s future financial sustainability.

The long-term demographic trend is that the state’s birth rate is declining, reimbursement rates from insurers have remained flat, and the average occupancy of the 80-bed NICU is around 40, thanks in part to innovative prevention programs that have reduced early-term births, and drug prices have kept increasing – the major driver of increasing health care costs in Rhode Island, according to recent studies. The coronavirus pandemic has further reduced the amount of time that moms have been spending in the hospital as well.

ConvergenceRI spoke last week with Colleen Ramos, MBA, vice president of Finance at Women & Infants Hospital, who has spent more than 30 years in hospital finance.

“From a financial perspective, my job is to make sure that we have enough revenue to cover the cost to take care of patients,” Ramos said. “To break even is the goal. And right now, we just struggle to break even, to cover our costs. I’m sure we are not the only one. But, it is hard to cover the costs of delivering high-quality care.”

One of the causes of the financial crunch, Ramos continued, has been the fact that the reimbursements from insurers have remained flat or declined. “When you look at what we get paid, the insurance companies are looking to save money, so, over time, for the same exact service, what they pay us has gone down,” she said. “We can’t decrease what we pay our staff, and every year, between what we pay our staff and overall inflation [of costs], whether it be for drugs or supplies, it is out of line.”

A couple of years ago, the trajectory changed, according to Ramos, where “expenses started to surpass the revenue that we bring in for the types of services that we offer.”

It is hard, Ramos said, reflecting on the challenges ahead. “As the provider, we’ve been doing the same thing, yet the insurance companies and the drug companies continue to make changes that I feel hurt us. It would be better if we were all working together, making sure that we are able to cover these costs to give this level of care to patients, without making it so hard for us. We look at every dollar here; we are efficient as we can be; we’ve cut out the fat, we have people that can doing multiple jobs, and all I can say when I look at the numbers is that revenue is flat and our volume is declining.”

Here is the ConvergenceRI interview with Colleen M. Ramos, MBA, vice president of finance at Women & Infants Hospital, talking candidly about the struggle to maintain financial sustainability as the state’s birth rate declines, reimbursement rates from insurers have remained flat, and the coronavirus pandemic has created limits to providing services.

ConvergenceRI: How long have you been working at Women & Infants?

RAMOS: I’ve been at Women & Infants for three and a half years. A year before that, I was with corporate Care New England. Altogether, I have been with the system for over four years.

ConvergenceRI: What is the current number of births that occur at Women & Infants Hospital?

RAMOS: We are at about 8,200 for the last year or so. And that number continues to decline. The previous year it was about 8,400. But if you go back to 2016, we were at 9,000.

The Rhode Island birth rate decline has been going on, I believe, since about 2008. We still have 80 percent of the market share, but the market has dwindled.

ConvergenceRI: The overall decline in the birth rate, it has nothing to do with the hospital, per se, it is a disliked fact that the birth rate in Rhode Island has declined.

RAMOS: Correct; correct.

ConvergenceRI: What are the reasons for that, do you think?

RAMOS: From the things that I have heard, the average age in the state of Rhode Island is up, and the balance between younger couples and older couples, I think, leans more toward the older generation.

On average, our population is older; younger families are not in Rhode Island.

ConvergenceRI: Full disclosure, my son was born at Women & Infants back in 1990. Women & Infants seems to be the first choice among so many residents to give birth. What do you think the reasons are for that? You have a greater than 80 percent market share. Have you conducted any research to confirm the reasons why people choose Women & Infants?

RAMOS: That is probably a little outside my expertise. I am vice president of finance. We have a planning department that looks at access and things like that.

I am from Rhode Island and my oldest son was also born here in 1990. My youngest was born at a different hospital, only because we lived outside of the area. From a personal perspective, reputation and things like that, brought me here.

ConvergenceRI: How big a factor has the COVID pandemic been in terms of how it has changed the dynamics and the finances around women’s health care?

RAMOS: It has impacted us in a couple of ways. Early on, last year, when we first started to feel the true impact, like everyone else, with the uncertainty, we canceled elective surgeries, we canceled a lot of outpatient imaging, things that were not emergencies.

People put them off; we took a hit that way. One of the impacts that people do not see, because we are still delivering babies, but we do not have the same visitation policy. People do not want to stay here as long, what we call “length of stay.” The amount of days that a mom is actually in our hospital has dramatically been reduced. That impacts us financially, for all of the services that we provide over so many days. Because of that drop, we were seeing some decline. As a result, there would have been more imaging, and more labs, and things like that. We are just seeing a decline in our overall business because of this.

When people used to have babies, I don’t know how long your son was actually here, but [before COVID] people could come in, grandparents could come in, and folks could come in and visit. We don’t have that anymore; we only have the birthing partner.

ConvergenceRI: In terms of my son’s birth we were fortunate that the delivery took place at around 9 p.m. on a Friday night, so we were able to stay through Sunday night. Three days was considered a long time back then.

RAMOS: That is about average these days. Our average length of stay, if you mix in some moms that having c-sections, three days is about our average, but we have seen that average decline because of COVID.

We don’t have outside vendors coming to take the first baby photos, and things like that. All that has changed.

ConvergenceRI: How has the pandemic changed the workplace, particularly the dynamics for women in the workplace, when it comes to women’s health care and maternal health?

RAMOS: We are seeing, especially with what is happening now across the country, especially with nurses, because of COVID, there is staffing shortage, with nurses.

We are all feeling it, not just Women & Infants, with the pandemic, and with the fact that it has been going on for so long, people are starting to get tired. I’ve seen some people just changing industries. They just, for whatever reason, cannot handle the same amount of work/life balance anymore. We have seen a lot of that; people couldn’t keep up the same commitment and work schedule.

ConvergenceRI: As you are trying to compute the financial bottom line, what would you say is the best metric to measure the value of women’s health care?

RAMOS: From a financial perspective? When you say value, you have a couple of different metrics. You have financial; then you’ve got quality, there are quite a few things.

ConvergenceRI: I will let you define it, however you feel comfortable talking about it.

RAMOS: From a financial perspective, my job is to make sure that we have enough revenue to cover the cost to take care of patients. To break even is the goal.

When you look at what we get paid, the insurance companies are looking to save money, so, over time, for the same exact service, what they pay us has gone down.

ConvergenceRI: Recent research conducted in Rhode Island has found that the major driver of increased medical cost, looking at the data from the All Payer Claims Database, is the increasing cost of pharmacy drugs. Has that finding held true with your experience?

RAMOS: I think for part of our services, the only real high costs drugs are with our cancer patients, for cancer drugs.

Insurance companies, they have implemented processes or programs to reduce their costs, which dictate where the patient can go to acquire the drugs.

For instance, there is a major payer in the industry that requires their members to actually purchase the chemo drug from what they call their specialty pharmacy. Where before, the patient got that drug from us.

Now, what happens is that all we are doing now is administering that drug, but remember, the revenue that we were bringing in before to purchase, deliver and administer the drug, we are no longer able to collect that revenue for the drug from the insurance company. But, when you think about it, we have all the same staff involved, administering the drug. So, it is a delicate balance of trying to stay ahead of all the changes.

ConvergenceRI: Part of what prompted my conversation with you was a statement from Dr. James Fanale, with you was a statement by Dr. James Fanale had given to The Boston Globe, in which he said, “I’m not so worried about Kent as I am about Women & Infants Hospital.” Can you talk about what Dr. Fanale meant by that?

RAMOS: The concerns are that we are a women’s specialty hospital, where Kent has a lot of opportunities to look at different service lines to balance their bottom line.

We have been in the same business, obviously, since our inception. As I mentioned earlier, insurance companies are paying us less to deliver babies. Unlike Kent, we cannot fall back on other service lines to make up for that loss.

Kent has orthopedics, it has cardiology, but we don’t those services at Women & Infants, we deliver babies, we take care of NICU babies, we take care of women with cancer, we have a GI program, and we have a behavioral health program for post-partum women.

ConvergenceRI: Way back when, when I interviewed Dennis Keefe, [the former president and CEO of Care New England], he said one of the problems, as he defined it, in running a world-class NICU was that it was expensive. At the same time, you have had enormous success in running numerous preventive programs that have cut down on the number of high-risk births.

RAMOS: Yup.

ConvergenceRI: And that sometimes creates a financial conundrum of sorts.

RAMOS: He was absolutely correct. Basically, because of medical advances, women are staying pregnant longer, so the number of really small babies that are born, we don’t see [the same volume] anymore.

When we look at, on average, how many babies we have in our NICU over he past several years, say for the last two years, it used to be in the mid-60s, now we seeing it go down to the 40s over the last year or two. And that means moms are staying pregnant longer and having healthier babies.

We have an 80-bed NICU, and because of staffing standards, we have a requirement of a ratio of how many nurses we have to have for those babies. We also have a lot of long-term nurses working here that have been here for 30-plus years, so they are at the top of the market. And the volume of babies in the NICU is declining. He [Keefe] was not wrong.

ConvergenceRI: It gets back to that question about how you measure value: the importance of having a world-class NICU and the fact that the more you decrease low-birth-weight babies or early delivery babies, you actually decrease all future health care costs. But that value doesn’t seem to get factored into the day-to-day equations.

RAMOS: It doesn’t get factored in, because how you decrease the costs? The way to decrease costs would be to lay off staff, which we are not going to do. And, if you are a NICU nurse, they are so specialized, the only place they could go to, if we were ever to lay them off, would be to Boston, which isn’t really an option for them.

So, what we try to do is through natural attrition, lower the amount of staffing that we have to match that volume. That will take a long time.

ConvergenceRI: Two recent series on Netflix, “Offspring” and “Virgin River,” seem to represent a real change in the way that women’s health care and maternal health care are portrayed, at least by Hollywood. The central characters are an obstetrician and a nurse midwife, and they talk about things like miscarriages, which is still not discussed in real life and very rarely in commercial productions. Do you think it is a good thing the way things have changed about talking about women’s health?

RAMOS: Again, all I can give you are areas that I have been involved in here, given that I am the finance person. I do know that one of the programs that we have, which I think is great, that doesn’t get talked about a lot, is focused on post-partum depression.

So, we have an OB Medicine program, and we also have a day hospital, so that basically, with these two programs, we have patients come in as far away as Maine, because of the services that we provide.

There is a medication that you are able to receive here, you get this infusion, and it literally, our physicians say, eliminate post-partum depression

Again, it is not glamorized, it is not a Hollywood topic; there are some women who commit suicide, post partum, because of the hormonal changes and the depression that they go through. The programs we have here are superb, because they end that. They end the cycle.

Another [innovative] program, it is a little bit different, I know about it because I was involved from a financial perspective, they call it the NAS [neonatal abstinence syndrome] program.

I don’t know if you have talked to anyone in our pediatric department or not…

ConvergenceRI: Yes, I have.

RAMOS: The program addresses neonatal abstinence syndrome. Basically, it is moms who have a drug addiction during pregnancy, and they work with a team here, they get medications and things like that to help them through the pregnancy.

And, as long as they stay in that program, the baby has a special protocol that they go through, and they work with the mom to make sure that the baby can stay with the family.

Think about it: if you are not in that program, and you come in and have a baby, and child welfare is notified that you have used drugs during the pregnancy, you have a risk of them taking your baby away form you while you are recovering.

And so, that’s another really good program we have here. I worked with the physicians here, because the state viewed them as normal newborns, whereas we were giving them services at the level of our NICU. I worked with them and talked to payers, and talked to the state, to say that these patients were truly getting a higher level of services, and we were able to increase our [reimbursement] rates for that population.

ConvergenceRI: I had done a story about Barry Lester and his work to create a better diagnostic tool, based on the audio cries of the infant, for neonatal abstinence syndrome. [See link below to ConvergenceRI story, “Shining a bright light on extraordinary research talent in RI.”]

It reflects on the excellence of Women & Infants to marry together research and clinical practice, and once again, the more that you increase the preventative nature of what you do, you can decrease future costs.

RAMOS: Yes, we do.

ConvergenceRI: I imagine that part of the challenge was trying to convince the insurance companies of the value of the program.

RAMOS: Honestly, it takes the bridging the clinical experts with the financial folks in order to make those arguments.

On the finance side, we are not always aware of where we might not be being paid for the higher levels of care that we have.

So, I wouldn’t know, unless one of our medical experts came to me, and said, “Colleen, the behavioral medication we are using [to treat post-partum depression], we were not getting paid for it.” And, that is how I found out about it, so I don’t find out about stuff until there is financial aspect to it.

We were not getting paid from one of the insurance companies for this very expensive drug that we were administering to eliminate post-partum depression, someone called me, and that is when we started looking into it. The same thing with the NAS program.

I think where our struggle is now is with our bread and butter, which is delivering babies, and when I looked at it recently, how much we are getting paid is flat, it has been flat for the last five years. Flat [reimbursements] – and a declining volume – is never going to pay for the cost of delivering excellent care.

That is what Dr. Fanale was leaning toward – we deliver all these babies, but we are not getting more revenue, it is flat, and we have the cost of living raises, and we have to pay higher costs on drugs, on medical supplies, what do you do?

ConvergenceRI: What you do is to talk to me and I then write a story about it.

RAMOS: [laughing] When I started, I have been in health care finance for 30 years, when I started it was so different, everything was done on a cost basis, the higher your costs were, that is what you got paid.

But obviously, for insurance companies to succeed, they have to manage higher costs as well, and I get it, but it is hard, we are taking care of people, and it is really, really hard to watch and not being paid for the services we provide, or not being paid at he level to be able to cover he costs of providing this care.

ConvergenceRI: Another program I have reported on is the nurse midwifery program, involved in training the medical residents from Brown.

RAMOS: We have 32 Brown OB residents; all of their training happens here, and the nurse midwives are part of that training.

Our director of nurse midwifery, Liz Howard, has been advocating for incorporating the doulas into our care models. All through COVID, we allowed doulas to come in; they are part of the birthing team. She has been educating the clinical staff and the providers on why it is important. They are showing how having a doula decreases the need for a c-section.

We are also working with the different payer and doing a research project. We are working with the doula community.

To read more on this story: http://newsletter.convergenceri.com/stories/women-infants-faces-a-financial-conundrum,6742

To read more RINewsToday stories by Richard Asinof: https://rinewstoday.com/richard-asinof/

_____

Richard Asinof is the founder and editor of ConvergenceRI, an online subscription newsletter offering news and analysis at the convergence of health, science, technology and innovation in Rhode Island.

_____