Search Posts

Recent Posts

- In the news: Quick recap of the week’s news… 6.14.25 June 14, 2025

- Drowning in corruption in Bonnet Shores: Hundreds sign petition. No action by lawmakers. June 14, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 14, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 14, 2025

- Burn with Kearns: Train smarter, not harder. Multi-use fitness tools – Kevin Kearns June 14, 2025

- Out & About in RI: Miriam Hospital Gala raises over $890,000 June 14, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

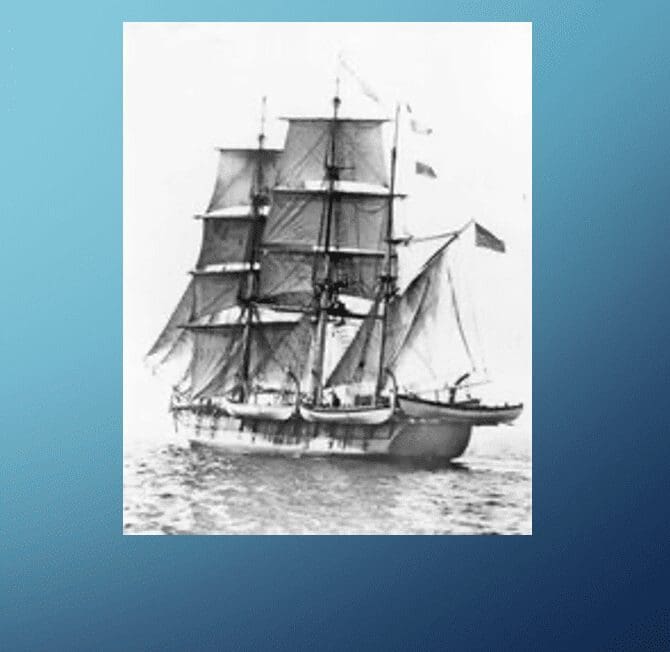

Tree-ring research confirming 1850s Rhode Island whaler found in South America

Off the coast of South America, a shipwreck has drawn the attention of Dendrochronologiasts, scientists who studies tree rings to determine dates and the chronological order of past events. They’ve been called in to help identify a shipwreck of a “whaler” a ship used to capture and process whales. In 1859, the globe-trotting ship, The Dolphin, from Warren, Rhode Island, was lost.

This month, The Dolphin appears to have been found – in Patagonia, off the southern part of South America, in the area of Puerto Madryn, Argentina, 6000 miles from home.

After years of studying the ship’s secrets, a team of scientists who use the study of tree-rings as part of archeological research has confirmed their findings of the ship being from Rhode Island and published them in Dendrochronology, their professional journal. Other artifacts and historical details from Argentina and Rhode Island have been studied, but this appears to be the first time tree-ring science has been applied to identify a South American shipwreck.

“It’s fascinating that people built this ship a long time ago in a New England city, and it turned to the other side of the world,” said study co-author Mukunda Rao, a Columbia tree-ring scientist.

Before petroleum

New England was a major player in the global whale trade from the mid-1770s to the 1850s, when oil extracted from blubber was popular for lighting and lubrication, and whale bone was used in small household items, now made of plastic. Hundreds of Yankee ships sailed to remote areas, often on voyages lasting years. The industry faded in the 1860s after the whale population was decimated – and petroleum arrived.

Dendrochronologists determined that the ribs of the ship were made of white oak, the hull and roof planks were old-growth yellow pine, and the wooden nails were made of black locust.

The North American Drought Atlas is a massive database and atlas built in the early 2000s that collates ring specimens from approximately 30,000 standing trees of many species for more than 2,000 years. The varying precipitation levels create subtle annual variations in ring width that allows researchers to chart where and when trees are cut because the climate varies, leaving individual regional signatures.

Theories that the ship was The Dolphin have been circulating for over ten years but the tree ring data is close to certifying it.

Photos: Columbia Climate School

The Dolphin.

The 110-foot whaling bark was built in 1850 by Chace and Davis, a shipbuilding firm in operation between Company and Sisson streets in Warren, Rhode Island, for much of the 19th century, according to Ted Hayes, in an article in 2012. “Parts of it show signs of having been burned and it is partially visible at low tide. Much of the structure above the keel is gone, leaving a section of wreckage about 80 feet long,” Hayes notes. While there are no “riches” to be recovered, it does document the long-lost history of the industry. The Dolphin was launched in October 1850, and historians think it was “probably the fastest square-rigger of all time.” One newspaper long ago description of the whaler in that the ship “outsailed every vessel it had fallen in with”.

259 barrels of sperm whale oil would have been a full load. Looking for whales was often a lonely and thankless task, going long stretches, perhaps, without finding any. Wrote the ship’s master, Capt. Cutler, on June 8,1852: “We are getting no oil. God help us and send us many whales so that we may put once more to a Christian land again to my dear wife and family.”

Though there are few records of the ship’s demise, her last captain wrote, “she lay upon the rocks in the southwestern part of New Bay.” The wreck saw 42 men rescued.

According to a Providence Journal archive, “Warren lost 14 whaling vessels during the Revolutionary War, and did not start whaling again until the early 1820s. Over the next 40 years, an average of 16 whalers per year sailed out of Warren, with crews of about 400 men. In total, the Providence paper notes, the average annual total of the products brought back — sperm oil, whale oil and whale bone — would have been worth about $8.5 million today. Shipbuilding was a big part of the local economy, too, and vessels were built in Warren that sailed out of many other ports, including Nantucket and New Bedford.”