Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Providence Delivers Summer Fun: Food, Water Play & Activities June 20, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 20, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 20, 2025

- Outdoors in RI: Time to Seastreak – Vets Access – Invasive Alerts – Clays 4 Charity at The Preserve – 2A TODAY June 20, 2025

- GriefSPEAK: Kill Switch – Mari Nardolillo Dias June 20, 2025

- Dr. Rosemary Costigan Named President of Community College of Rhode Island June 19, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

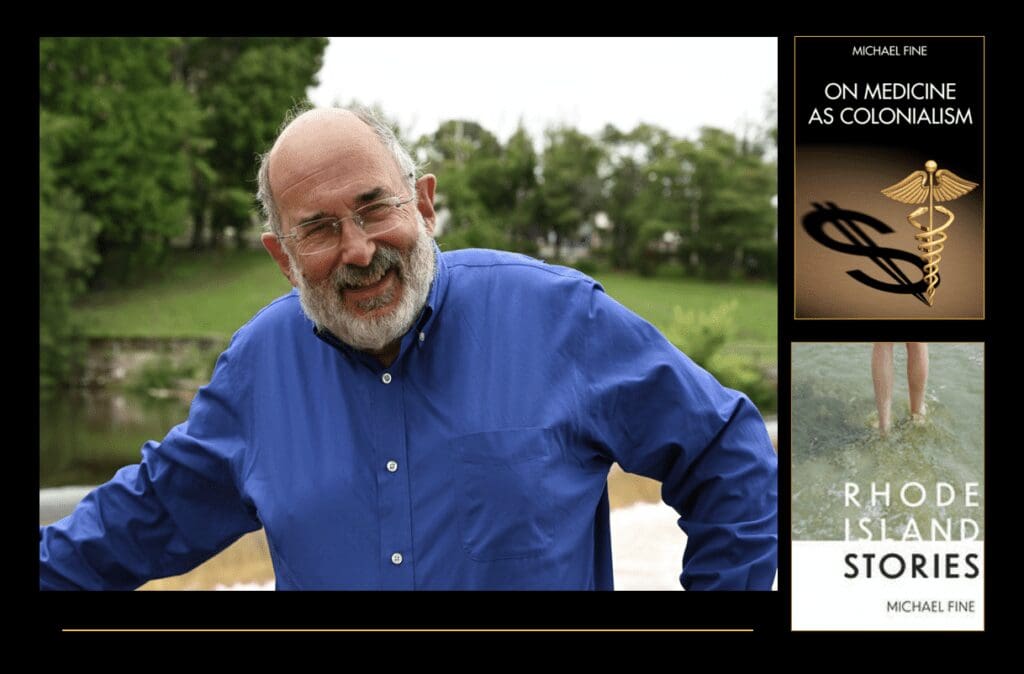

The Nadir: a short story by Michael Fine

By Michael Fine, contributing writer

Copyright © 2024 Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

There is a week in winter in the Northeast when the Earth appears to stop in its tracks, as if it had stopped spinning on its axis. It’s the coldest week of the year, usually in late January. The temperature never gets above freezing for days or weeks in a row. The car doors won’t open. A glaze of ice covers the windows. The pipes freeze. The sun stays low in the sky the whole brief day. The winter birds ruffle their feathers against the cold, and the branches on the trees click or snap when the wind blows, or they glisten, crusted with ice. The cold air makes the skin constrict, the eyes tear and the lungs burn.

Craig Brown steered the Bobcat straight as you go as he drove it up the ramp onto the trailer. Done here, he thought. And done for a couple of weeks. They had worked through December and through January in the middle of a pandemic. Got away with murder, from an excavator’s point of view. Work or die. They worked, a good thing because there’s no way to make payments on machinery that sits idle. But now a hard freeze was coming so Craig would sit home for a couple of weeks. Maybe plow if they got a good snow. Maybe drive to Florida.

He threw the straps on and winched them down. Then he raised the ramp. His 350 had no trouble pulling this baby, but he eased his way down the drive and onto the street. No rush. No place to go. Time to build himself a fire and find himself a good woman or maybe a good book.

Crystal Barden would have been pissed when the rig pulled into the parking lot had there been any more cars parked there. The truck and the trailer took up enough space to fit seven or eight cars, and now it blocked the entrance to the diner from Route 6 coming west. But there was a pandemic on and nobody much came into the diner these days. You get a little rush Sundays when people who used to go to church just couldn’t get out of the habit of having breakfast out anyway. You get the take-out rush at dinnertime on Friday, maybe fifteen or twenty, one right after the next, the few people working outside their houses picking something up on their way home from work. But that was about it.

Some guys who work construction would do take out coffee in the mornings. They were building a new convenience store down the street, and the guys who were working there did take-out for lunch, more days than not. Once in a while the GC would take a booth and work at the diner for a couple of hours, spreading plans over the table and working with a calculator, but that was about it. Not much happening at work. Not much happening at home either, truth be told. Text messages, once in a while. Waste of time.

It was midwinter. There was no place to go and no one to go anywhere with. Life on ice. Nothing ventured, nothing gained. Therefore nothing gained.

Craig Brown was an excavator, a guy who moved small mountains of dirt and dug big holes with big machines. Foundations, trenches, ponds when DEM let him, which was almost never. Cleared brush. Knocked over trees to get them out of the way. Hauled fill and gravel to make roads.

The good news was that work didn’t dry up the way Craig thought it would when the pandemic hit. He had a break for three or four weeks at first when everything stopped while people tried to figure out whether they were going to die or not, and then everyone tried to figure out what they were going to do and how they were going to do it. But then things got back to normal pretty quick. Better than normal, to be honest. No one had anywhere to go or anyone to go there with, but money kept pouring in for most of the people Craig knew.

So people started projects. A new barn here. A new garage there. Solar farms. New roads through the woods. New houses. Site development for new little subdivisions on parcels most people thought weren’t good for anything.

Craig expected the stock market to crash and that everything would grind to a halt. Empty shelves. No traffic on the streets. No work. Power outages. Food and gas shortages. Then runs on banks and then the banking system shuts down. Then marauding bands roaming the streets, in camouflage, wearing bullet proof vests, with AK-47s, talking on communicators with drones flying overhead as they looted neighborhoods. You give the boys toys and they are going to use them. Only a matter of time.

The world had been out of balance for a long time. Too much power. Too much power in too few hands, true, but also just too much of too much. People didn’t really have to work anymore. Or most of the work people did wasn’t really work. They go to meetings. They sit in rooms with other people. They make up stories about one another. They design things that aren’t real. Is a video game real? How about an App? What is an email that goes viral, really? Just a short burst of electrons, not even the least breeze.

It was strange. A global pandemic and life goes on, except people are supposed to stay home and wear masks? Everyone stays home but the whole economy keeps humming along, like it was on autopilot.

Not that what Criag did was real either. One man shouldn’t be able to put a rift in the earth the size of a city bus with the touch of a button and by shifting gears that swing a steel bucket around. One man shouldn’t be able to lift pieces of ledge the size of a car, or push over a hundred-foot-tall oak or hickory that had been planted by the wind or by a squirrel burrowing in the ground a whole century ago, and then buck that tree into logs with a chain saw that screamed louder than any beast on earth could scream, a chain saw that one man can hold and control but dissembled a gracious old tree that God had made.

You ever sit in the cab of a decent sized backhoe? You feel invincible.

Those cowboys with guns, they’re no different. You send people to Iraq and Afghanistan and teach them counterinsurgency warfare with artillery and air support, and then you expect them to come home and work security at Walmart? Or be cops in the suburbs?

Still, none of the chaos Craig had expected happened. Yet. A couple of weeks of not enough toilet paper, that’s all. Shortage of flour. But mostly no change. As if nothing mattered any more. As if nothing could change the arc of history, which has brought us to video games, tract houses, and gender identity issues. This old aircraft carrier just kept on sailing. Didn’t turn one degree. Sailing God only knows to where.

The only bad news was that Craig’s son, John, couldn’t come out to work with Craig now. John’s wife, Christine, couldn’t work from home. She was a nurse who used to work nights, so he could be home with the kids during the day. The hospital needed her for days now, with so many people in the hospital and so many nurses out sick. Sometimes she worked 48 hours in a row. So John had to be home with those two little kids. Which wasn’t great for Craig. But not a bad problem to have, compared to what other people were dealing with.

That meant Craig was flying solo now. Alone much of the time. Which was no disaster either. No one blathering stupidity. No fake news or empty factoids. No one to yank his chain.

Craig parked in front of the diner, put on his damned mask and went inside, alone.

The rig took up seven or eight parking spaces, but none of that mattered now. The ground was frozen, life had slowed to a crawl, and nobody cared much about anything other than getting through the day. Or night. Because everyone was just waiting for the long days to return. Not that the life they had before really mattered. Not that anyone did much more than do again what they had done the day before, that they all weren’t doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result. Not that there was anything to look forward to, any reason to expect any love, hope, or change.

The bells over the door jangled as the door whooshed shut.

There was only one woman working the front and her back was to the door. Masked and working behind a wall of Plexiglas, like she was an animal in a zoo or a teller at a bank. We are a divided people, Craig thought. A divided nation. Good fences make good neighbors.

“Can I help you?” Crystal said as she turned around. And then froze.

“Black coffee and a donut,” Craig said. “No. Make that a piece of blueberry pie, please,” he said as he noticed the pies displayed in a stainless-steel case behind the counter.

But Crystal didn’t move.

“Coffee and a piece of blueberry pie, please. Think you can find me a table? Or are you not serving here yet?”

“Sit anywhere,” Crystal said. And she turned so the man before her couldn’t see her face, turned to the pie case and the coffee, which was in a glass carafe, steaming on a hot plate. One glass pitcher, on a hot plate that had room for four.

There was a now a wall of Plexiglass between the counter and the space where servers stood. A wall of gleaming stainless steel behind that space for the servers. The kitchen was on the other side of the stainless-steel wall through a door that had swinging louvered half-doors. Craig turned and found a booth for four, right in front of the plate glass window that looked out onto the parking lot, so he could keep an eye on his rig.

People are distant now, he thought. Once upon a time the waitress or server or whatever would have given him some lip or a little backtalk or done something to make him feel welcome. Half-flirting, the way servers in diners do, not so much as to invite trouble, but enough to make it clear that they and you are both alive. Alive enough. Maybe. Sometimes more.

But nothing from this broad. From this woman. From this server. Whatever.

Less than nothing.

Craig looked at his cell. Which was a waste of time. To kill time. While he warmed up.

He didn’t look up when the server brought his coffee.

“Black,” she said. “Sugar against the wall.”

And then she turned away before he could answer.

“I like it black,” Craig said. “No sugar. I like things just the way they are. Not gussied up.”

“Some people never change,” she muttered as she walked away.

What’s that about? Craig thought. He looked at the juke box offerings which were displayed on the table in a little glass fronted cabinet that had a speaker built into it, another relic from another time, and then out the window again.

“Pie,” the woman said, as she dropped a thick white plate on the red linoleum table, her voice also thick with attitude. Which made Craig look at her for the first time.

Crystal. Holy cow.

Crystal had dumped him, once upon a time, but he deserved it. Thirty years before. He was all full of himself then, not that he was that much different now. But back then, he thought he owned the world, that the world owed him a living and a big living at that, because he was such a talented guy.

They hadn’t been together that long – a couple of months, maybe a year. But her walking out on him still stung. He could still feel the bitterness, how his mouth just dried out when she told him, in the parking lot in Garden City where they were used to meeting, where they met one last time so she could give him his keys back. How he swayed a little when he walked, unsteady on his feet. How he threw the keys at the ground, ready to stalk off, and how he almost fell over when he bent down to pick up the keys. How half of his anger was an act, because a part of him was relieved that she dumped him — because she took up so much of his time and attention, because she got to him in a way he had never expected any woman would, so he thought about her too much, and he wanted to please her too much, as if she’d become an addiction. She had made his life damned complicated, because she was a burden in a certain way, an obligation, an extra responsibility that he hadn’t wanted, an encumberment.

It wasn’t until later, when she was gone, that this pit opened in his stomach, that this hand came from out of nowhere, grabbed his backbone and began twisting it, and then it reached into his throat and grabbed his innards and twisted them, so he couldn’t breathe, couldn’t think, and wanted only for someone to put a bullet into his brain, to take him out of his misery. It was like a part of his soul had been cut away, a part he never knew was there. She had been a stone around his neck, a whole lot of extra weight that he resented carrying, and she felt that in him, which was why she dumped him. But she had also been the other half of himself, the person who was what he wasn’t, the poetic side, the ethereal side, the spiritual side, the sensuous side, the side that contained all his hopes and dreams.

You don’t think much about other people when you are in the moment, when the thing is happening. You don’t think about what you feel. You just do it, pulled along by the current, and bounce from rock to rock.

It didn’t matter at first. Go ahead. Be that way, he thought. Your loss, baby. Go jump in a lake. But then it made him suddenly and surprisingly nauseous, losing her. He panicked. Craig didn’t think he had any emotions, but only thoughts, calculations, estimates, and plans. So this feeling, this self-reviling self-hatred, this disgust and sadness and fear all rolled into one, it was strange. Weird. Alien.

At first, he thought her dumping him stung because her didn’t like losing. She went off with someone else, a guy they both knew, Charlie, who he didn’t think much of, whose reach was longer than his grasp was strong, who wasn’t the brightest bulb. Serves them both right.

But then it began to gnaw at him, like a rat gnawing on the door to a cupboard in the middle of the night. He stopped sleeping. He played it over and over in his mind, the way he threw his keys down and stalked off, what she said and how she said it, that there was really no place for her in his life and she was going to be with Charlie now, a man she could count on. All bullshit, of course. All just words. She wasn’t his type. She wasn’t really that stable. Look at the mess she had made of her own life. He was better off this way. Too much entanglement. Life should be simple, not complicated. He didn’t want to owe anyone anything. Free and clear, that’s how a man should live. With no woman telling him what to do.

But then this terrible hole opened in his soul, as if part of him, half of him or even more than half had been stolen, had been cut off, taken out and buried, as if his legs and pelvis had been amputated at the waist.

He rode out to her house and drove on her street to see which cars were parked there. He parked across the street in the middle of the night and sat there, watching. He searched the oncoming traffic for her car, conscious as he was doing it how crazy he’d become. He picked up the phone to dial her number, once, twice, a hundred times, and listened to all her messages on his answering machine, over and over, and reread all her emails, because this had all happened after the internet came but back before cellphones and texts.

He dreamed about her. They were always still together, in his dreams, and she was always still in his bed. But then a deep chasm had opened in his dream, under her, and she fell into it. She grabbed one of his hands as she was falling, like a scene from the movies when the hero catches someone as they slip and are falling over a cliff and are holding them by one hand, their fingers slipping out of the hero’s grasp until the hero makes a superhuman effort and lifts the falling person onto the cliff.

But he couldn’t hold her. In his dream, he felt her fingers lose their grasp, one by one, and then he watched her fall.

He’d wake up from those dreams with a start, and then feel around in the bed for her, somehow not understanding deep inside himself that she was gone. What was astounding was how this kept happening, once in a while, across thirty years and in spite of him being with other women.

How he’d wake and go looking for her. And find someone else in her place.

He survived. You survive. Or maybe you go crazy and kill someone or kill yourself.

But that wasn’t Criag. He was tougher than that. Or not. Maybe just stubborn. It messed him up for months. But it didn’t change him. Much.

He waited but she didn’t come back. She had recognized him first. That was what the attitude was about. He was sure of it.

He sat still and looked out the window. That cold front was coming in. Sleet now, falling on the truck and the backhoe. Soon snow. Then ice. The ground will freeze three feet down. Nothing would move. You can move machinery when that happens. They don’t get stuck in the snow. The machines have weight, so much mass that they don’t slip and slide the way a car does. They just keep coming on. You can’t use them though. Not with snow on the ground and everything frozen like that. So you have to sit still and wait until the nadir passes. Until the ground thaws.

The coffee had warmed Craig’s core. Pretty good coffee. A little bitter and a lot real. Not like the Starbuck’s Kool-Aid.

The pie was gone. Pretty good pie.

“You needing anything else?” Crystal said. She had come out from behind the Plexiglass, and lifted the thick white plate which was now stained by the deep blue-purple pie filling.

“Hey Crystal,” Craig said.

“You knew?” Crystal said.

“I figured it out.” Craig said. “I heard you. Still pigheaded and still more than a little blind. Still sometimes can’t see what’s right in front of my eyes. But you know how to communicate. And I got the message, eventually. Just like old times.”

“That’s different. I didn’t know you ever got the message,” Crystal said. “Any message.”

“The bugs in my head are so advanced that they started a space program to tunnel out through my thick skull?” Craig said.

“Something like that.”

“Not my proudest moment,” Craig said. “I fucked it up. Me. All me. I was sorry about it then. And I’m still sorry about it now. One of a thousand bad choices. I didn’t know you worked here. I haven’t been here in like, ten or twenty years. No place to park.”

“Uh huh,” Crystal said. “The more things change, the more they stay the same.”

“I could say I follow you on Facebook, I suppose. But I don’t do Facebook.”

“One small step for man. You wouldn’t have found anything. I don’t do Facebook either.”

“Well then maybe there is something we share,” Craig said.

“One thing. One tiny little thing. But let’s not get carried away,” Crystal said.

“Look, I take responsibility for my choices. My actions. You can take that for an apology if you want. Or not. It’s been thirty years. Good to see you and all that. Let’s just let sleeping dogs lie.” Craig said. He reached for his wallet, pulled out a bill, and tossed it on the table.

“Keep the change,” he said, and he stood up and started to pull his coat on.

“You could have reached out a little.” Crystal said. “Like once or twice in the last thirty years. Or done something then. Tried a little harder. Hell, tried a little. Like once. But that just isn’t who you are.”

“You have no idea who I am,” Craig said. “Never did. Never will. That’s not who you are either.”

“What do you know about who I am? About who I was? About who I’ve become? Nice to see you again,” Crystal said, and she spun around.

The bells over the door jangled and two old people came in, a bald white guy with jowls and rheumy eyes and a wrinkled bend-over woman with tan skin and curly white hair who walked with a walker, her back was bent in half.

“Sit anywhere,” Crystal said.

Jesus, Craig said to himself. Don’t these people know about the damned virus? That it kills old folks. Don’t they know to stay home?

He shook his head as he talked through the door. Some people never change, he told himself. Good riddance to bad rubbish.

The bells over the door jangled again as Craig walked into the cold air.

Damn, he said to himself. No rest for the weary.

Then, just as he was unlocking the door to the truck, he felt something. A feeling in the pit of his stomach, a nausea, the sudden sense of his life slipping away, the feeling left over from those dreams, the ones where Crystal’s hand and then fingers slipped from his grasp. That was followed by the sense that the bottom half of him had just been cut off and dumped into a pit and that the inside of him was being twisted into a ball, as if someone had just shoved a hand through his throat, grabbed his heart and was twisting it.

What the hell? he wondered. Where is that shit coming from? This thing has been dead and gone for thirty years.

He climbed into the truck.

He turned the starter and the truck’s engine roared to life.

There’s nothing quite like sitting in the cab of a big diesel truck as the damned thing belches black smoke. Nothing you can’t do with a truck like that. No place you can’t go.

He put the truck into gear. Drove slowly forward.

And then without warning, Craig stopped the truck.

He turned the ignition off. He sat for a minute or two.

Then he opened the truck door and stepped onto the ground, the springs of the truck sighing a bit as his weight shifted from it.

He shook his head, cursed to himself, and walked across the empty parking lot.

Then he mounted the steps to go back into the diner.

You only live once, he thought. Better later than never.

___

Many thanks to Carol Levitt and Catherine Procaccini for proofreading and to Brianna Benjamin for all-around help and support.

Please click here to receive Michael Fine’s monthly short stories and his new series, What’s Crazy in Health Care. Please invite others to join by sending them the link here.

Information about Michael’s books, stories, posts, talks and performances is available at www.MichaelFineMD.com or by clicking the link here. Join us!

___

Read more short stories by Michael Fine, go here: https://rinewstoday.com/dr-michael-fine/