Search Posts

Recent Posts

- New ALS treatment by PathMaker Neurosystems. Co. funded by RI Life Sciences Hub to come to RI. June 3, 2025

- ART! Cape Verdean Art at New Bedford Whaling Museum June 3, 2025

- Brown University Health names Samuel M. Mencoff Chair of the Board June 3, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 3, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 3, 2025

- Why 13-15 Rhode Island cities and towns oppose weapons ban legislation being voted on TODAY June 3, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

The joy of hating modernism – David Brussat

by David Brussat, Architecture Here and There, contributing writer on architecture

Photo: New national library proposed by the late Jan Kaplicky for Prague

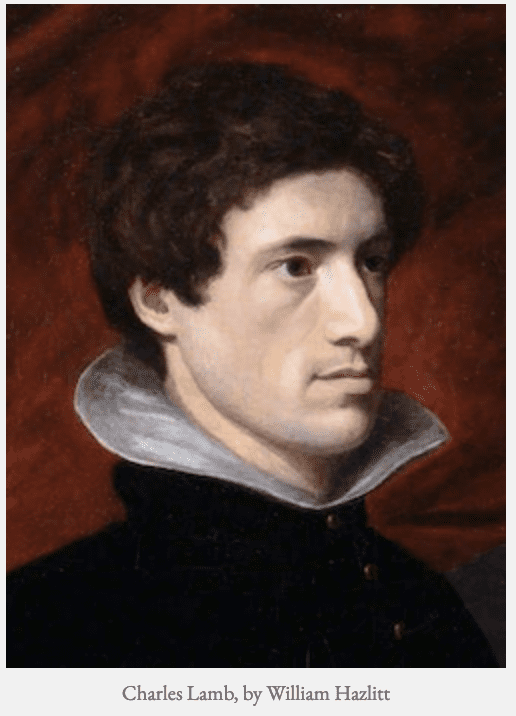

My favorite writer of all time is William Hazlitt, the British essayist of the early 19th century and contemporary of Charles Lamb and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. He was considered a “good hater” (or maybe it was “a good damner”) and in fact wrote an essay called “On the Pleasure of Hating,” in which he writes, “Nature seems (the more we look into it) made up of antipathies: without something to hate, we should lose the very spring of thought and action.”

I imagine myself to be a professional hater of modern architecture. and pride myself on developing, in my posts, a scaffolding of denunciation that reaches peaks of hatred for it that will impress readers with my comprehension of its many, many mortal flaws. But I just received an email from the historian James Stevens Curl, author of Making Dystopia (2018), that contains a paragraph that surpasses, so far as I can recall, anything I have ever written.

Here is the email, which regards the absence of beauty in modern architecture. First he writes of an anonymous modernist architect (not the late Jan Kaplicky, whose unbuilt work is pictured above) who “boasted that he ‘does not do beautiful buildings,’ which is obvious from a perusal of his work.” Curl then writes:

Modernism in architecture is responsible for untold misery, appalling ugliness, and worldwide destruction. It is used by powerful interests to impose the will to destruction of that which is humane in architecture and town planning. It is repulsive, alien, cruel, and beyond redemption. Its theorists and apologists pump out breathtakingly ignorant guff dressed up in bogus intellectual pretensions, all resembling the mating-calls of an air-conditioner. The public should wake up, reject mass calisthenics, and refuse to believe what it is told by architectural bullies whose failures are legion. And the texts churned out in support of modernist architecture should be seen for what they are: distorted, lying travesties of real history, written with a leaden grasp of prose usually found in booklets of instruction for washing machines translated from the Japanese.

Some of this may seem, to some, a little over the top, or even psychotic. But if anything Curl’s denunciation is generosity itself, and yet hatred is often balanced by a will to beauty. Curl has that. Love for beauty clearly animates Curl’s hatred for modern architecture. Love and generosity often spring from the same breast as hatred. This may be seen in Hazlitt’s essays on painting. He was himself a fine painter, early in his career. His portrait of Charles Lamb hangs in the British Portrait Gallery. In “The Pleasure of Painting,” he writes: “There is a pleasure in painting which none but painters know. In writing, you have to contend with the world; in painting, you have only to carry on a friendly strife with Nature.” In that essay, written in 1821, Hazlitt continues:

The mind is calm, and full at the same time. The hand and eye are equally employed. In tracing the commonest object, a plant or the stump of a tree, you learn something every moment. You perceive unexpected differences, and discover likenesses where you looked for no such thing. You try to set down what you see – find out your error, and correct it. You need not play tricks, or purposely mistake: with all your pains, you are still far short of the mark. Patience grows out of the endless pursuit, and turns it into a luxury. A streak in a flower, a wrinkle in a leaf, a tinge in a cloud, a stain in an old wall or ruin grey, are seized with avidity as the spolia optima of this sort of mental warfare, and furnish out labour for another day.

Soon after, Hazlitt writes:

With every stroke of the brush, a new field of inquiry is laid open; new difficulties arise, and new triumphs are prepared over them. By comparing the imitation with the original, you see what you have done, and how much you have still to do. The test of the senses is severer than that of fancy, and an over-match even for the delusions of our self-love. One part of a picture shames another, and you determine to paint up to yourself, if you cannot come up to nature. Every object becomes lustrous from the light thrown back upon it by the mirror of art: and by the aid of the pencil we may be said to touch and handle the objects of sight. The air-wove visions that hover on the verge of existence have a bodily presence given them on the canvas: the form of beauty is changed into a substance: the dream and the glory of the universe is made “palpable to feeling as to sight.”

_____

To read other articles by David Brussat: https://rinewstoday.com/david-brussat-contributing-writer/

My freelance writing and editing on architecture and others addresses issues of design and culture locally and globally. I am a member of the board of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which bestowed an Arthur Ross Award on me in 2002. I work from Providence, R.I., where I live with my wife Victoria, my son Billy and our cat Gato. If you would like to employ my writing and editing to improve your work, please email me at my consultancy, dbrussat@gmail.com, or call (401) 351-0457