Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Providence Delivers Summer Fun: Food, Water Play & Activities June 20, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 20, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 20, 2025

- Outdoors in RI: Time to Seastreak – Vets Access – Invasive Alerts – Clays 4 Charity at The Preserve – 2A TODAY June 20, 2025

- GriefSPEAK: Kill Switch – Mari Nardolillo Dias June 20, 2025

- Dr. Rosemary Costigan Named President of Community College of Rhode Island June 19, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

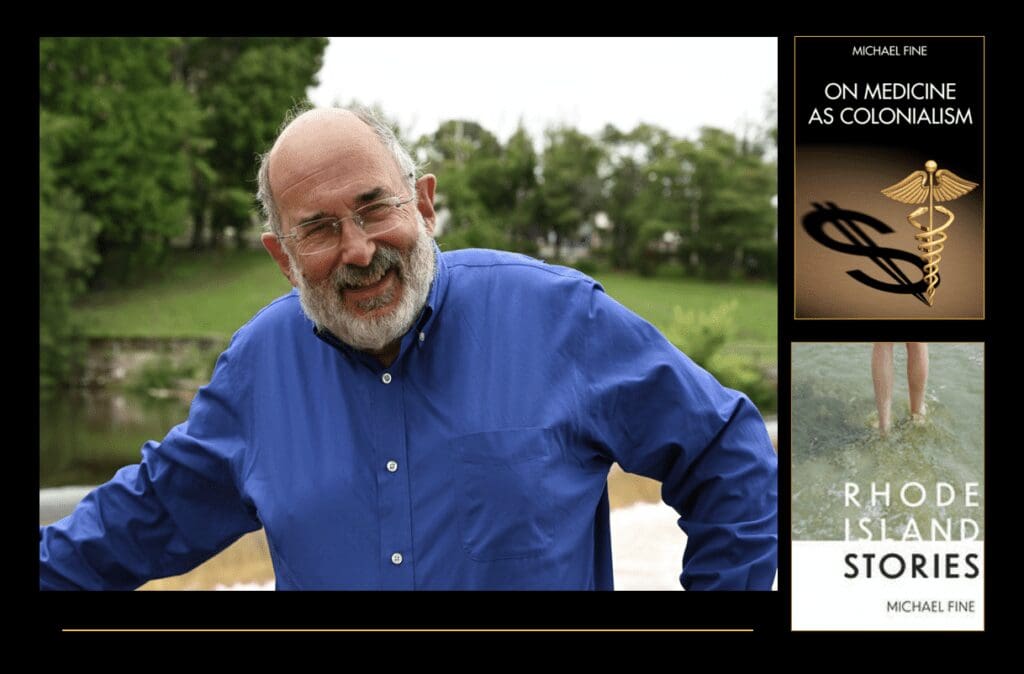

The Force That Drives All Flesh: a short story by Michael Fine

By Michael Fine

© 2024 by Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

___

When Yudi awoke, the sun was already high in the sky and was streaming through the clouds. There was mist rising off the meadow. The air was cool. Their tattered sleeping bag was wet with dew. They were next to a broken cement block wall, with charred wooden beams from a collapsed roof piled next to them. I must have pushed all that crap out of the way when I got here, Yudi thought, but their head ached and their back, neck, arms and chest hurt in a way that told them getting here wasn’t simple or safe, not that they knew where they were. Their head more than hurt. It was heavy, all fogged up – a stone between their eyes, where their thinking was supposed to be, and the thinking wasn’t happening. Must have hit my head as well, they thought. A concussion or something. How long have I been here? Where is here? The air stank of charcoal. Had this thing, this building, burned already? They wondered. Or did I burn it down?

Their bike lay against one of the broken walls, the frame bent. It was a kid’s red bike with a banana seat with monkey bars and streamers on the handgrips.

West Virginia. Could that be? Where John Brown came to free the slaves. Harper’s Ferry. A river valley in a mountain town deep in the middle of nowhere. John Brown was a crazy man who got a great notion in his head that he couldn’t get quit of. Take seven crazy white men, three of whom were John Brown’s sons, two free Black men, three runaway slaves, and make war on the United States of America to free the slaves. Enslaved people will rise up all across the Southland, and humanity will be free of slavery forever. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord. And so forth.

Now Yudi remembered. Rode the rails to Martinsburg, West Virginia, a place history forgot, and capitalism rediscovered. Which was now just corporate business parks and strip malls in the low hills. Hitched rides or walked to Charlestown, West Virginia. They didn’t think people would stop for people who looked like them and most didn’t, hitchhiking no longer being a thing, but people stopped now and again anyway, mostly hefty young men driving black pickups with American flags streaming out the back and upswept chrome exhausts that belched black smoke, men who wanted mostly to insult them or needle them or look at them out of the corners of their eyes, asking infuriating, micro-aggressive questions about how and what he did to who, like they themselves were confused about themselves. Those men turned off after a mile or two, Baruch Hashem, after their curiosity or whatever was satisfied without violence, thank God, though violence was also in the human soul and Yudi was prepared to accept that as the price of being who they were, who they had become. Up to a point…

Or they got picked up by people who looked like they did, part of this strange crew, this tribe, the people who had lost themselves and thought the self should stay lost because it is the self that keeps wreaking destruction on the world, on the earth, the tribe with pink and blue hair and lots of tats and piercings, who picked them up to show their solidarity but also were only going a mile or two themselves, usually to the Dollar Store, where half of the clerks looked like they did and the other half were young women who wore pants and had pony tails who said ya’ll and ‘come see us’ and blushed easily. So, they mostly walked but arrived alive, despite the known risks of walking or living while queer, especially in West Virginia.

In Charlestown they found the bike in an old barn that looked like it had been abandoned. The bike was covered by black dust and the tires were both flat, but they blew the tires up at an old Citgo which you could tell used to be a Mobil station because it still had the flying horse. You have to pay to use the air-hose now most places but the air hose at that Citgo was free. They wiped that bike down with an old towel and tied their pack to the back of that banana seat. Then they rode west over the hills and mountains as the sun was setting.

That was most of what Yudi remembered.

They got themselves out of that sleeping bag and stood up. They had on shorts which were dry. The air on their chest was cool, even cold, but they were not cold yet – they were still warm from the sleeping bag which had not soaked through. There were puddles on the ground so you could tell it had rained. The clothing Yudi must have stripped off, the shirt and jeans and socks, they were wet. Their pack was wet, at least on the outside because Yudi had not put a tarp over it the way they usually did, so they must have been drunk or stoned or hurt bad or two of those or three when they laid down to sleep. They didn’t remember that part yet. The sun was stronger now but there were clouds gathering, purple clouds heavy with rain, on the western horizon. Yudi laid out their clothes on that broken up cinder block wall where a building used to be for the sun to dry and then opened their pack and took out what was wet and laid it out on that wall as well.

But then the sky got dark. There was lightning and then thunder. And then a horrible sound like a locomotive coming right at them. Yudi looked up. There was a locomotive coming at them. They had been sleeping right next to train tracks which ran just behind the collapsed building where they’d slept. There was a big old freight barreling down those tracks. That old freight was moving way too fast for Yudi to jump out of the way, even if Yudi had their shit together which clearly they did not. Literally and figuratively. But the locomotive stayed on the railroad tracks and missed them.

The freight passed by.

Then it got worse. The sky got green and black, and the wind came up and the leaves got stripped off the trees and were blown at Yudi so hard that those leaves hurt when they hit their face and arms and head, and the rain came sideways with hail that hammered at them, so they put their hands over their head. There was another roar, like the freight train but louder — hollow, beastly and rumbling. They collapsed, their hands over their head, their knees and their chest pulled into a fetal position as the branches of the trees near the railroad track cracked and groaned as they broke off the trees and then the trees themselves were uprooted and came crashing down in the roar of the wind. Yudi couldn’t think yet, but they were thinking that they were about to die.

And then the hail stopped, leaving a crust of hailstones over the earth.

There was a bar, Yudi remembered. They stopped before sunset for a bowl of soup. They had been to Harper’s Ferry. They rode through the town, down a long hill to the river and the place where the ammunition dump that John Brown and company had captured and held for two days; the government troops that took it back led, most amazingly, by Robert E Lee himself. In 1859, two years before the start of the Civil War. John Brown hadn’t figured out how to tell all the slaves in the surrounding farms about the rebellion once it started. He forgot to stop a train that paused in Harper’s Ferry the night the rebellion began, and that train carried the word of the rebellion to the authorities, who sent Lee and troops to put the rebellion down. And so, the rebellion had failed, a missed opportunity, perhaps or a misguided folly that cost the lives of at least eighteen people and wounded about the same number, with another seven. Including John Brown himself, executed for mounting the insurrection, back in the days when we thought insurrection was an actual crime, when irrational hope, poorly translated into action, had meaning and caught the imagination of the nation, however wrong-headed the raid itself was.

The rain stopped. The wind stopped. The sun poked through the clouds.

They were still alive. Yudi stood up.

Men fight in bars sometimes. Sometimes people dance. Love, or whatever, happens there.

They did not want to see what they saw. They had a uniform and a gun then. At seventeen. They wanted to come through Mahal — Mitnadvei Hutz Laaretz — Volunteers from Abroad, but that does not exist anymore. They grew up in Providence, Rhode Island, a Day School kid. Lived for Torah but needed a break at seventeen. Not concentrating. Unhappy. Heartbroken for no reason. Starvation in the midst of plenty. Something was missing. There had to be something more.

Seventh child. They thought of buying an old car, to drive across America, visiting our communities along the way: Baltimore, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, Memphis, LA. You are not ready for that, my father said, and I could see my mother agree with her eyes and then she spoke to me after because my father is wise but distant. My mother knows. Knows me. Knows the world.

I despaired. You can do other things for now, until you are ready to learn again, my mother said. Like what? I said. Work in 7-Eleven? I barely read English or know math. Can I make change? Sell real estate?

Israel, my mother said. Go there now. Your brother and sister are there. It is a good place for Jews. My family is here, I said. Israel, to visit, yes. But I am not ready for Aliyah. No one said Aliyah, my mother said. I could join the Army, I said. We all want to join the Army in some part of us. We hear the shofar and think of Joshua and the walls that fell down.

My mother hesitated. She thought of me as learning, as under the huppa and as the father of her grandchildren, not any other way. She looked into me for a long time.

You can go, she said. I’ll talk to your father. And you’ll learn in a different way and become a man a second time and then you will come back to us. Better than in an old car driving across America where things happen. There is Netzah Yehudah, she said, where they pray and learn. There is Netzah Yehuda, I said, thinking about how to pray and learn but also march and be at checkpoints — but not fight, not yet, having never been in Samaria, having never been in the West Bank. So not understanding what happens in those places.

And so there was that checkpoint, at 3 AM, and the Palestinian man who spoke English, angry that we stopped him. We dragged him from his car when he didn’t have a passport. Not me. I stood there holding a gun, not sure why we were there, wanting only to leave people be. Wanting peace not war. He spoke English. An old man. He spoke like he was from the Midwest, with big vowels and lots of r’s. Spoke mostly through the nose. Caught, which sounds like cot. Warsh the car. Close the lights. Yeah no, for sure. What are you doing? Who do you think you are? He thought he was in America because we spoke English to him. We bound his hands with zip ties and put duct tape over his mouth and then he groaned and collapsed on us. And we left him, anxious to get away. Next to a broken-down cement block wall. Back to base. And then we davened shacharit when the sun rose.

That man is what I see when lightening illuminates the darkness. We left him on his stomach, next to a broken cement block wall like this one.

It was silent. They were alone. Wet, cold and alone. Far from everyone.

Lonely, they had asked a man to dance. Then there had been a fight in that bar. The men beat Yudi senseless. Dragged them out to a truck. Drove the truck over his bike as he was beginning to wake up and threw Yudi and the bike into the truck and drove the truck out of town. And dumped them for dead by the railroad tracks, like Yudi’s unit had dumped the old man in that building in Jiljilya. Also at 3 AM.

Here I am, Yudi thought. And said out loud. Adonai, Here I am. Me. Yudi. Asking you, asking God, to see me. To hear me. To tell me which way to go. The world is terrible and terrifying. We are destroying the earth. What is to be done?

They were asking, in their own way, to die. To be relieved of this burden, of these choices. Adonai, the Omnipresent. Adonai, the Omnipotent. Adonai Lord of hosts. Take my life. I don’t have the courage to go on. Not that I have the courage to end my own life, which is forbidden.

In return, silence.

The terrifying sound of that silence.

You can die, the words in their own head formed at last, in that silence. There was no voice. Just stillness. The universe will be fine without you. Life goes on. Mistakes are made. Things happen in wartime. But those mistakes vanish, dissolved by the arc of history. History is made by the victors. The universe is made by energy that congeals into matter. What of the energy that fails to congeal? It is nothing. A passing shadow. A wilted flower. A dream that can’t be recalled. Nothing.

They say the evil impulse is the impulse to dark acts. But the most evil moment is not even an impulse. It is nothing. Silence. Absence. Unfilled space. Why are you here?

I am so alone, Yudi said.

Nu? So?

I thought I could live for Torah, for truth.

You are alone in a field in West Virgina after being beaten up in a bar fight. So much for Torah. So much for truth. So much for you.

The Law matters. The truth matters.

To who? For what? Is it your law? Is it your truth?

What is it all for? Yudi said.

Nothing. Meaning is an illusion, a Jedi mind game, something people use to justify their short, meaningless, miserable lives.

There is pain in the world. You made pain.

You mean suffering. There is suffering in the world. But people made suffering. People have pain and let one another suffer. So?

We could be better than this.

How do you know? You could be worse than this. Or just evaporate, like a puddle on blacktop after a rain when the sun comes out.

What am I going to do?

Probably nothing.

When?

Probably now. If at all. Or you could evaporate. Makes no difference to me.

If I am not for myself who will be? If I am for myself alone, what good am I? If not now, then when?

Babberdash. Just more words. Your distraction. So, you give yourself an excuse not to act. Take your own life, if you are so miserable. I dare you. That’s the only way this endless drivel of self-deception will ever stop.

They started to shiver.

How to get warm when everything is wet? And cold. Standing there in their underwear. They saw their pack in a tree next to the railroad tracks, the one tree still standing, where it had been snagged when the whirlwind took it. They found a branch that had been stripped of leaves and used the branch to knock the pack out of the tree. Inside the pack were still a few things — a pair of jeans and the tarp they should have put over the pack, not that it would have mattered, not that the whirlwind wouldn’t have blown it away. A pair of socks.

They thought of something. The little zippered front pocket was still zipped. They unzipped it. Inside was a baggie that held a book of matches wrapped in Saran Wrap. One thing they did right. Perhaps the only thing. They unwrapped the matches. Their teeth were clattering and their hands wet shaking with the cold. Hypothermia, they thought. A perfectly good way for my miserable life to end. They turned over the charred logs from the ruined building they’d slept in. Chucks of charchol fell off the logs. There were leaves that were dry underneath. And twigs from the branch they used to free their pack.

They made a fire. They pulled cement blocks from the wall into a circle around the fire. And warmed their hands.

The cement blocks came from somewhere. Being out of nothingness. That force made the matches. The charcoal. The logs. The fire itself. The force that drives all flesh made the fire.

Being is better than nothingness. The force that drives all flesh also made Yudi themself.

Life is endless heartbreak. There is free will, but only one choice. Which is to live and struggle to survive. Or not. In case tomorrow is better than today. But probably won’t be. The force that drives all flesh drives us that way as well. Endlessly.

For no purpose perhaps. Other than hope itself – that against all odds, that we and it and everything might matter. And only if we and they do what is right and just for once, however unlikely it is that decency and justice will matter.

The clouds were still thick and threatening, but there was blue sky in places.

Yudi warmed themself. They dried their clothing. They stuffed their clothes into their backpack. Then they put on their socks which had been made stiff as they dried by the fire. They rolled the still wet-in-places sleeping bag and tied it onto the pack.

Then they hoisted the pack onto their queer shoulders and stumbled onto the train tracks, to walk until sunset, or to jump a freight in one slowed enough around a curve, their head bloodied but not unbowed.

___

Many thanks to Carol Levitt for proofreading, to Jim Lucht and Kathy Morton for catching and helping me fix even more mistakes, and to Brianna Benjamin for all-around help and support.

Please click here to receive Michael Fine’s monthly short stories and his new series, What’s Crazy in Health Care. Please invite others to join by sending them the link here.

Information about Michael’s books, stories, posts, talks and performances is available at www.MichaelFineMD.com or by clicking the link here. Join us!

___

Read more short stories by Michael Fine, go here: https://rinewstoday.com/dr-michael-fine/

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor in Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.