Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Benefits for seniors from Rhode Island’s next budget – Herb Weiss June 17, 2024

- Rhode Island Weather for June 17, 2024 – John Donnelly June 17, 2024

- South Water St. will restore traffic lanes, expand parking, move bike lanes. Not till 2025, for $4M June 17, 2024

- Embracing change is the future of work – Mary T. O’Sullivan June 17, 2024

- CES Boxing lights up Mohegan – John Cardullo June 17, 2024

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

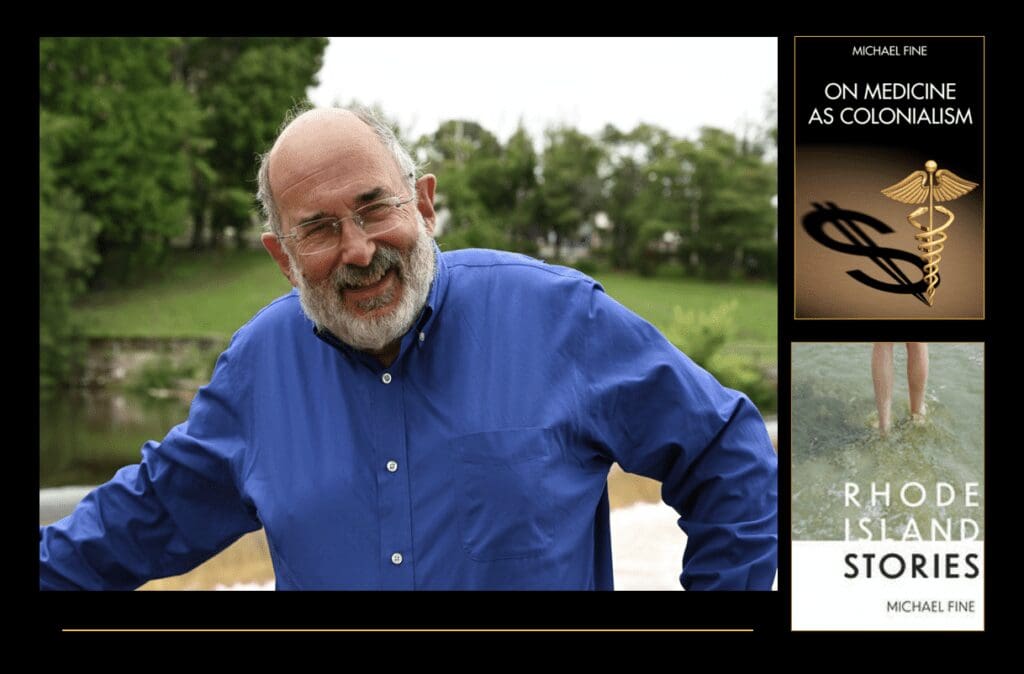

The Eclipse of the Sun by the Moon – a short story by Michael Fine

By Michael Fine, contributing writer

In Memory of Damien Sobel

© 2024 by Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

There weren’t bombs falling on Przemysl, at least not yet. No bombs and no missiles. It was April. There were white cherry blossoms on the brown-barked cherry trees in the villages on both sides of the border; the narcissus were in bloom and everywhere there were brilliant yellow flowers. The grass in the village commons had turned green, the hillsides were covered with the green stems and tiny yellow flowers of rapeseed, and the air was filled with the moist, earthy smell of plowed ground.

There had been a missile attack on Lvov. The Russians had bombed a training center for foreign volunteers in Yavoriv, just twelve miles from the border, but everyone was still being careful, trying not to trigger a nuclear war. NATO brought troops to the border but was careful not to bring fighting brigades into Ukraine. The Europeans and Americans were still playing footsie with what weapons they gave Zelensky, drawing a distinction between offensive and defensive weapons. Putin, on his side, had avoided bombing too close to the border, most of the time, understanding that NATO had zero tolerance for that or for missiles that just happened to stray into Poland or Romania, and were even watching over Moldova.

But there were Patriot missile batteries around all the runways in Rzeszow and along all the border, and everyone knew the whole thing could explode, without any warning, that these idiots could actually incinerate all human life, essentially by accident, the result of one man’s manipulation and greed, and the weakness, moral corruption and narcissism that pervades the West.

.

Sara Jane wasn’t going into Ukraine. That was the deal she made with her mother. Everything else she’d done so far was a little crazy perhaps, but not risky at the end of the day. Leaving her consulting gig on a moment’s notice, a month before her locums in the north was to start. Getting into a van with Gillian who she barely knew, taking an overnight ferry and then driving for twenty-four hours across five countries and showing up, first in Przemysl and then in Medyka with only a three-day Airbnb reservation at a place six miles from Medyka. Knowing no one in Poland or Ukraine and not speaking Polish or Ukrainian or even Russian. You can stand and watch history, Sara Jane told herself, or you can try to tilt the balance towards justice. Bend the arc of the moral universe, the Americans say.

Putin was Hitler and Stalin redux. He was evil incarnate, attempting to bend the world to his will, with no reason for doing that other than that he could. And the rest of us were just chumps, just blind and selfish, statues without hearts, a consuming mass who refused to learn from history. Why should we exist at all? if we allowed this kind of human madness to run riot over the world again and again. Who are we? Do we have no backbone? No heart? No sense?

.

The truth was that Sara Jane’s life wasn’t any better than any other life and perhaps more disordered than most. She had a good enough brain and was a far better doctor than most. Maybe even a great doctor, because she knew how to listen and she never took ‘no’ for an answer, which is how you need to be, if you are going to deliver for your patients in the NHS.

But Sara Jane had no real direction. She was easily bored, was not good at following other people’s rules, and had no tolerance for fools, which was unfortunate because the world is full of fools, people who do nothing besides wait in a queue and do what they are told to do, following empty ideas and trends blindly, believing what they are told. Her romantic life had been a bust. She fell in love with another student at university who turned out to be more depressed than strong and silent – she had invented a personality for him he didn’t have, which made him more depressed yet until he attempted suicide, one day when they were near the end of their term, and then, after they got his stomach pumped, he told her he was gay so they split up, and then she saw him next six months later, with another woman.

She fell for one of her teachers, a senior doctor in the practice she joined up north to get away from all that. Said senior doctor was married. They began to see one another on the sly for six months, and then the moment he began to actually acknowledge who she was as a person, to actually regard her instead of just being inflamed by the heat and novelty of an affair, by the tawdriness and the mystique of sneaking around, Sara Jane herself fell for a woman, a tall blond artic looking woman with blinding blue eyes, the first Ukrainian Sara Jane had ever met, a nurse who had emigrated with her parents ten years before to work as a fashion model, and had no interest in Sara Jane at all.

Her nurse tolerated Sara Jane’s company from time to time, even welcomed it, when she wasn’t with a man, but said nurse had no romantic or sexual interest in Sara Jane whatsoever, and Sara Jane herself, who had never experienced anything like that kind of attraction, didn’t know what to do with her feelings at all, but let her little affair with the senior doctor wither. That caused Sara Jane to lose her place in the practice, when her colleagues, who mostly wanted to go home on time, take long vacations and drive nice cars, began to see Sara Jane as selfish and self-serving, bothersome, and hectoring. Sara Jane was always chasing after measures and indicators – the vaccination rate, treatment-to-goal for hypertensives, screening for diabetes, opt-out testing for HIV – that might be nice enough for the public’s health and important enough to the NHS but that just didn’t matter that much to her colleagues. They were good enough, according to the measures, without all the extra work. It was fine to be a little above average. No one other than Sara Jane wanted to win any prizes, because there really wasn’t that much money in it.

Sara Jane herself didn’t want to win any prizes. All she wanted was for them to be the very best they could be. But what her colleagues understood was that Sara Jane didn’t really care about them at all. They understood that Sara Jane wasn’t going to protect them as they protected one another, and that she didn’t understand her place, which was to come in, see her patients, make her home visits and be otherwise invisible.

But that invisibility disappeared when she caused awkwardness and disruption by becoming involved with one of them and then had the temerity to drop him.

Sara Jane finally realized was that the thoughts, opinions, and feelings of her colleagues didn’t matter that much to her either. Which was what aggrieved them so much. But she couldn’t see why that should matter. And so, she was more surprised than shocked when they failed to renew her contract, even though she was the best doctor in the practice by far.

.

But none of that prepared Sara Jane for the border.

When you come like this to the border of a war-torn country to try to help, you don’t have any clear idea of what you are doing, other than having the impulse to try to do something to help.

As with the rest of her life, Sara Jane didn’t have a plan or a strategy. She knew only that the world was more out of control than she was. Her brain told her that if everyone did something, if everyone did their part, the world might regain its order, and everything might go back to how it used to be.

She imagined the border as a dark, cold place, lit by torches, always raining, set against a backdrop of explosions and jets and missiles screaming as they flew low overhead. She imagined hordes of wounded Ukrainian soldiers, international volunteers, wounded old farmers in dark brown cloth coats and overalls and gnarled old women in babushkas streaming over the border on crutches or carried on gurneys, their bandages blood soaked. She imagined sophisticated field hospitals with generators and emergency lighting and surgeons operating in the open, triaging as they went, amputating arms and legs in the field, placing chest tubes, and repairing one life threatening wound after the next. She pictured bushels and baskets of bloody bandages. She saw herself as responsible for aftercare, that she would round on fifty or a hundred patients every-day in dimly lit tents, and make life and death decisions, saving most, but losing more patients than she’d ever lost before, and she steeled herself for that eventuality.

.

The border was nothing like that, of course. There were tents to be sure, but they were tents with brightly colored signs, lining a paved pathway that led from and to the border itself to a bus stop about two hundred yards away, the buses headed to the train station in Przemysl, and then via those trains to Warsaw and Krakow, to Budapest, Berlin, Prague and Paris. Medyka was the only place on the Ukrainian-Polish border people could cross on foot, so people came in cars and buses and trains to the border, and sometimes they walked. They queued for hours and sometimes days at the Ukrainian border control, which made sure no men of military age left the country, and then queued again to get through Polish immigration and border control, often waiting twelve or twenty hours or more.

And then they walked again, down a little hill, through no man’s land between the countries, a plowed field to their left, on the other side of a chain linked fence and then barbed wire and coils of razor wire, with a couple of spindly cherry trees growing near the fence, and a few larger trees at the top of the hill, the cherries in bloom despite themselves.

Then those the people flowed over the border and entered Poland itself, many pulling wheeled suitcases that rattled when they were pulled over the pavers on the poured cement walk. As they emerged from no man’s land into Poland, they were met by volunteers in orange or blue vests, people from France and Israel, Denmark, Germany, the UK and Ireland and Poland itself, who greeted the refugees and then put their suitcases and other bundles into shopping carts from a bankrupt shopping centre in Przemysl and walked with them down the paved path between the brightly colored tents of the NGOs to the buses to Przemysl and thence toward the next step in life.

A few refugees were like the people Sara Jane expected but most were different. Some were in fact gnarled old men in overalls and bent over old crone-like women in babushkas, wearing black coats, and some even walked on canes and on crutches. But most were younger people and families who looked like they lived in council estates, women with spiky bleached hair, men over sixty who were overweight and balding, the retired lorry drivers and auto mechanics and police and firemen and insurance salesmen of Ukraine, the women, the school teachers and sales clerks and hairdressers of Ukraine, the children, kids in faux American t-shirts and down parkas carrying cheap school backpacks made to look like American cartoon characters — Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Snow White and My Little Pony — the detritus of a culture that was trivial, commercial and immature but had spread around the globe none the less, bad culture always driving decent culture out of circulation. Some had skateboards. Others rode scooters.

The atmosphere was a strained version of a carnival, because the NGO tents on both sides of the walk that made the place look like a street market or a carnival itself – people giving out hot coffee and all kinds of food – tiny Mandarin oranges, slices of pizza, energy bars, chai tea, French fries, and pancakes – as well as phone cards, scarfs, hats, and plastic ponchos and raincoats. There were tents from international refugee organizations, tents for women who had been physically and sexually abused, even tents for dogs and cats and other pets, so they could be fed and cared for. Medical tents with makeshift examining tables and surgical lights, and boxes and boxes of donated, expired medicine. World Central Kitchen. A Chinese group that opposed the Communist regime. A right wing Polish political party.

The mix of people who walked between the tents reminded Sara Jane of the working class crowds at the Bullring in Birmingham or of the crowds who used to walk the piers in Blackpool in the summer, looking for nothing beyond donkey rides and Blackpool rocks, their lives such that a rock of crystallized sugar or a ride on a carousel or roller coaster or even on a donkey could bring pleasure in a way that their day-to-day lives did not.

Nothing prepared Sara Jane for the triviality of the medicine that she would practice on the border. There were no litters, no helicopters, and no field hospitals on the border. There were just little first aid tents, one staffed by Israelis from an organization of right-wing West Bank settlers, one staffed by German Ahamdiyya Muslims, and one staffed by Polish paramedics from that right wing Polish political party. People came in off the cobbled path to ask for medicine for headache, or to have their blood pressure checked, or to see if there was blood pressure medicine like the medicine they had left behind in Eastern Ukraine.

Sara Jane found a new Airbnb flat in the city center with five other women and then established herself with the Ahamdiyya Muslims. But there just wasn’t much to do. Sara Jane stood in a tent as the refugees walked past, or she chatted with people from around the world, who had all come to try to help. Once Sara Jane sewed a laceration. Another time she gave a tall female volunteer from Scotland a neck massage to treat a stiff neck. Occasionally she put a plaster on a superficial cut or a scrape.

Why have I come? Sara Jane asked herself. What hole in myself am I trying to fill?

But then she put that line of thinking aside. I know what’s empty. Forty-five years old. No partner. No kids. No real job. Too opinionated and difficult to get along with. Bright perhaps. I have friends. And family I love. But what good is my intelligence if I can’t make a real life for myself like other people do, with a job and a family and a house and something approaching unconditional love? I have freedom, which is a good thing. But what good is freedom if I don’t have deep connections, in a world that is in flames, with freedom and democracy dying all over the world, everywhere you look.

Mark, one of the other volunteer doctors, a pudgy Canadian, arranged to start crossing the border every day. He went with a team and met a driver on the other side of the border and made rounds of schools and orphanages where the internally displaced refugees had come, the people who fled Eastern Ukraine and the Russian onslaught there, who had run from Mariupol and Kramatorsk as the bombs were falling, people who were now staying in elementary schools or one of the vacant cottages in farming villages, the people who didn’t want to leave Ukraine but had run for their lives. Mark was doing real medicine. He was putting himself out there, not worrying about borders or bombs. Sara Jane, on the other hand, was doing nothing, hiding, not doing much because she had promised her mother that she would not go into Ukraine itself. She felt silly. All her medical training and all her skills were going to waste, giving out plasters and paracetamol.

.

And then they heard about the buses.

There would be ten buses of evacuees, coming in the morning from the Eastern provinces, from the war zone itself. The buses were headed to Germany, an act of mercy by the German government and people, bringing the wounded and shellshocked to safe harbor and hospitals in Berlin. The buses were evacuating people from bomb shelters and hospitals and would drive all night to reach the border. They would stop at a refugee center about an hour north of Medyka, and then drive all night again to cross Poland, hoping to have all those people safe in hospital or in hospice in Berlin by midday the following day.

No one knew the condition of the refugees, or how well or sick they were, and whether they could stand another twenty-four hours on a bus. So, the NGOs put together assessment teams. We’ll meet the buses as they come across, the NGOs said, and make sure they are well enough to complete the trip. We’ll bring doctors and nurses and check every person. We’ll have food and bathrooms. Be ready.

Probably no big deal, Sara Jane thought. Just blood pressure checks and more paracetamol. But maybe, just maybe, I can be a bit useful for once.

The teams assembled on the border at half six in the morning, just as the sun was rising, an orange streak in a thin grey to blueish sky among the just emerging leaves, while the morning birds were chattering. The teams climbed into jitneys for their own trip, about an hour north, to the refugee center near a more northern border crossing.

Sara Jane was cold and only grudgingly awake. She found herself in a white World Central Kitchen jitney, in the front seat with seven colleagues jammed into the back, and only barely noticed the driver, a lanky man of about forty with a scraggly beard and a friendly but also intense expression.

“Can you please turn up the heat?” Sara Jane said, only half aware that she was grumbling, and sorry about the way her voice sounded as soon as the words left her mouth.

The driver turned and flipped a dial with one hand as he drove. A blast of warm air flowed over Sara Jane. It warmed her core in a way that surprised her. She was so expecting to be cold the whole trip.

“Absolutely,” the driver said, in English but with a precise Polish accent.

.

And somehow, that was all it took. One word. One single word. In that low, secure, precise, confident, and sensual voice. One word. And Sara Jane was hooked, in a way she had never been hooked before.

They talk about how people go weak at the knees, and Sara Jane never understood what that could possibly mean until then. But there it was. She was weak in the knees, and she wasn’t even standing up. Her back and pelvis got squooshy. The muscles of her back and shoulders melted, her body and her soul warming together. Her heart began to flutter in her chest. She was a doctor, by God. Hearts don’t flutter unless there is a diagnosable rhythm disturbance. Doctors, particularly damned good ones like she was, don’t get weak in the knees. Sara Jane was always in control. She was trained to keep herself calm and to focus in the most extreme situations, even though she was only a GP. She was all about taking charge, and making things come out right, about taking responsibility herself and not waiting for someone else to act.

And now here was this man, who had come from nowhere, who was making her head spin early on a Tuesday morning before she’d had her coffee.

“Cheers,” Sara Jane said. “And you are…?”

“Darien,” the man said, his voice almost a growl, drenched in confidence, in certainty, in the moment.

“I’m Sara Jane,” she said. ‘Are you ok in English?”

“I’m fine in English. In Polish. In German. In Russian. And in Ukrainian, although my Ukrainian is vestigial. But it has blossomed in the last two months, necessity being the mother of invention. I’m glad for the new proficiency, but heartbroken about its cause.”

Oxbridge. No Cambridge. Very clear. Sara Jane hated the Oxbridge types and their hoity-toity self-assured self-importance. But this man wasn’t like that at all. Humble. Kind. And this Polish man spoke better English than Sara Jane did. He spoke with precision and with clarity. But without pretense.

Here was this beautiful, brilliant man, driving a jitney on the Polish border with grace and with humility, and speaking in a voice that was clear, present, and thrilling.

Before she knew what had happened, they were at the refugee center thirty miles north on the border, and the buses began to arrive.

The refugee center was an old warehouse and distribution center, a big open drafty steel walled building thrown up over a poured concrete floor. No inside walls and no rooms. People had thrown up room dividers, just jerry-rigged walls that were eight feet high under a sixteen-foot-tall ceiling, so the place looked immense despite those dividers – as though you could walk for a mile under that roof and still keep walking. Cavernous. There was no heat, of course, because the warehouse was too big to heat. There were hastily constructed toilets near the entrance, and sections thrown up by the NGOs – a section for clothing, piled high with bales of clothing of all sorts and sizes, all jumbled together for refugees to sort through, hoping to find something that fit. There were booths constructed by various governments, by the Germans, the Italians, the British and the Irish, the Spaniards and the Portuguese, to provide immigration information for people who planned to go on to those places, although none of those booths were manned right at the moment, and booths from UNHCR, Save the Children, the International Rescue Committee, World Vision, the Danish Refugee Council and Oxfam, but those booths were also thinly manned, so there were few actual human beings about. It felt like each person in the refugee center was a space capsule, lost in a dark cold and unfeeling universe.

World Central Kitchen had a bright dispensary set up in the middle of the building, with piles of mandarins, of small loaves of bread, of thousands of water bottles, and its volunteers were busy, bringing in cartons of food on hand trucks and pallet trucks, as they dished out portions from steam tables and refilled the coffee and tea urns. The World Central Kitchen people were the only real humans in that place, and their dispensary was the only part of the building where people were coming and going, like bees in a hive, a center of light and warmth in a place that otherwise seemed huge and desolate.

.

The first bus was blue. It had the flags of Austria, the European Union, and the Red Cross brightly displayed on its front and rear windshield. Its left and right rearview mirrors hung off the body of the bus and looked like tentacles, so the bus itself looked like a large squat insect, the light reflected off its windshield the way light is flecked off the compound eyes of a fly.

The doors of the bus opened, and people, those people who could walk, began to stream off. They streamed into the refugee center, headed for the toilets and the coffee or for a cigarette. Some had been on the bus for thirty-six hours and had come directly from the war zone. The air smelled of sweat and sewage, of blood and of diesel fumes all at once.

This will be quick, Sara Jane thought. I’ll go in and see who has run out of their medicine and get them the medicines that they need.

.

It wasn’t quick.

.

The bus was still stuffed with people, a Noah’s ark of humanity, two of every kind of person, all talking at once, all traumatized, all suffering but all somehow still alive and shyly resolute.

Sara Jane went on board with a translator, a third-year medical student named Sylvie, from Kharkiv, whose medical school had been blown up by the Russians and who was living on the border, helping in any way she could. Sara Jane had a blood pressure cuff and a pulse oximeter, her stethoscope, and her wits. That was all. She didn’t need to fix all the problems. Technically, she didn’t need to fix any problem at all. Her job was only to identify anyone who was too weak to survive another twenty-four hours in the bus, take them off, and get them to medical help in Poland, in another country whose language she didn’t speak and whose medical system she didn’t understand. Take them off and then what? Drive them to a hospital? Drop them off on the hospital’s front door?

The people on the bus, however, didn’t understand any of that. They didn’t know she was a doctor. All they knew was that she had a white coat and carried a stethoscope. Something for my stomach, one of them said. Something for my headache. For my nerves. For sleep. Everyone spoke, demanded, or yelled at once. In Ukrainian and Russian.

And at the same time, there were plenty of people who worried Sara Jane, whose health seemed precarious. Two men with no legs scooted down the aisle of the bus on their hands and lowered themselves down the bus stairs with gravity-defying precision, like daring young men on a flying trapeze. An old woman in a red babushka with one eye. The overweight middle-aged woman with terrible pitting edema, with legs the size of tree trunks and skin that oozed clear fluid through bandages. The rail thin old man with a barrel chest who coughed thick gobs of yellow and green-grey sputum. The disabled people who seemed ageless, pasty skinned and with grey patchy hair, sitting in adult diapers that needed to be changed.

It was hard to know where to begin. So Sara Jane just dived in.

She started at the front and worked her way back, Sophie speaking for her. Have you ever been in the hospital overnight? Do you take any medicine every day? Which medicine? When did you take your insulin last? Are you short of breath? Are you having any chest pain. Yes, I will get you medicine. Maybe not your medicine. But some medicine, medicine that I promise will work. This is all we have. It isn’t perfect but will make you more comfortable until you get to Berlin, where there will be more doctors and more medicines. No we do not have an x-ray machine here. That is in Berlin.

The hardest thing was getting the people in diapers, the people missing arms or legs or had legs in bandages or casts, off the bus and inside to the refugee center, for their diapers or their dressings to be changed or so they could use the toilet, and then getting them a change of clothing and a coffee and a sandwich or a cup of soup. There were helpers to do that, of course. But getting even one person off the bus was a major struggle. It took three helpers to extract each person and then to maneuver them down the too narrow aisle of the bus, down the stairs, into a wheelchair and then into the refugee center, work made all the more complicated by the many people who were able to walk on their own, who were coming on and off the bus after using the toilet and eating or drinking something or standing outside smoking for as long as they could, which made the plaza in front of the bus smell like cigarette smoke, bitter and stale, the smell of burnt paper.

.

Darien was present on the bus. Present but unobstructive, almost unseen. He was there when he needed to be. He popped in and out of the bus with trays of food and canisters of coffee. He was there to help, a third or fourth set of hands, when someone had to be moved off or back on the bus. He didn’t say much. But he caught Sara Jane’s eyes from time to time as she was working. He watched this woman who had been half asleep in the jitney next to him a few hours before transformed into an engine of energy, concern and organization. Sara Jane could feel Darien watching her do what she did best, which was take control and make people feel safe, even while they were all unsafe. The back of Sara Jane’s neck and the pit of her stomach got warm and that made her work even harder, as if Darien’s attention had filled her sails in a new way, and inflamed her, had made her larger and more confident and more in control even than she was, as she drove herself to get all these people squared away, safe and sound, toileted and fed, changed and freshened up, and to get this bus moving again, on its way to Berlin and safety.

Sara Jane recognized something strange in Damien that she knew from herself, which seemed inappropriate, given that they had only just met and had barely exchanged a hundred words: he was a whole soul. He seemed solid, honest, and present, and only wanted to help. And somehow wanted her. As she wanted him. An impossible and meaningless perception, given where they were, what they were doing, and the complete absence of any meaningful possibility that any of what Sara Jane was feeling was real, which didn’t matter anyway because Sara Jane had her hands completely full, being a doctor to all these people, almost all by herself.

It took almost two hours for the people on the first bus to get squared away. Sara Jane felt enormous relief as she walked down the steps of that bus and then more relief as the bus roared away to the west.

The sky was still overcast, the air cold and smelling of diesel fumes, and spats of rain splattered down intermittently as Sara Jane stood on the tarmac. Even so her shoulders and her neck began to relax, and she took a deep cleansing breath, the kind she often recommended to others. She looked around. She needed a massage and a pair of strong hands holding her, soothing her neck and shoulders. But no one was close by.

The second bus arrived.

Then it started to rain continuously, a cold driving rain that made standing outside miserable.

Ten buses. One after the next. Each bus a replica of the last. What did the Americans say? Give your tired, your poor, your huddled masses, yearning to breathe free? Here they were, the tired and the poor of Ukraine, huddled in buses, inching their way west, from bombardment and degradation to freedom and light

Darien was there, in and out. Sara Jane was conscious of him, but there was no time to do or be anything other than what she was, a lone doctor in a cataclysm, a lone presence standing there amidst forces far more powerful than she could ever hope to be, a blade of grass or a slip of paper, standing alone in a hurricane. Tempest-tossed indeed.

I will find that guy when I’m done, Sare Jane thought, in the back of her mind, as she was processing all the people on the bus before her. I’ll get him to drive me back to Przemysl. Then maybe we can go for a drink. And see what, if anything there is to this, those feelings, this consciousness, which is entirely unnecessary and inappropriate. And then perhaps let nature take its course.

Then the last bus arrived.

The last bus was nothing like the other ten buses. The last bus had all its seats removed. The floor of the bus was covered with mattresses. Lying on the mattresses were twenty people, bodies really, the patients of a custodial care home in Kramatorsk that had been evacuated as the bombs fell. They were women, mostly, perhaps, but it was hard to tell gender or age. They were people with profound disabilities, people who didn’t speak or didn’t hear and had no control of bowel and bladder, most of them, adults in diapers, laying on stained sheets on mattresses on the floor of a bus with the seats taken out, murmuring and mumbling gibberish. In Ukrainian. And some cried out or howled when they were touched.

Sara Jane held her breath, for a moment, because the smell wasn’t good.

Then she plunged in, climbed the steps of the bus, and knelt down next to first one and then the next. Sara Jane touched each one, regarded each, and made a plan for each. Change of diaper here. Zinc ointment to reddened skin there. Change of clothes, change of bedsheets, change of position. They had caretakers who had traveled with them, but the caretakers were shell-shocked themselves and barely able to speak. The caretakers hadn’t addressed their patients’ needs on the trip. So those people were lying in diapers, in their own excrement, in urine and feces and drool-soaked brown bed sheets and soaked, stinking bed clothing. They needed everything. Which Sara Jane then got them, mustering the last bit of energy she had and puffing up the exhausted NGO volunteers, as they went from person to person, changing diapers, sponge-bathing some, changing the bandages of others, and getting them dry clothes and new sheets, so their journey could continue.

The moon was full and the stars were out when they finished with that bus. The rain stopped and the rain clouds had blown away from under the moon. The temperature had dropped. Ice was forming on the roadways, although it was April – the last frost, perhaps, in a year when the weather didn’t seem to matter much anymore, in a year when only the acts and egos of men and nations seemed to matter, a year when human beings had perfected their ability to ignore the earth that birthed them.

The World Central Kitchen jitneys were long gone. The refugee center had closed for the night. There were four or five NGO cars still in the parking lot, and Sara Jane got a ride back to Przemysl with a woman volunteer from Germany who was born in Turkey and had a rental car that she used to transport the few people still on site. The woman dropped Sara Jane in the city center, on the cobbled streets in front of her flat.

What Sara Jane didn’t expect was to find Darien sitting outside of her rented flat, sitting on a bench in front of the little Italian restaurant that was next to the entrance to that flat. He was wrapped in a blanket and was sipping a steaming cup of coffee. There was a thermos of hot coffee on the table. He poured out a second cup as Sara Jane approached and he stood and wrapped his arms and the blanket around Sara Jane as she collapsed, and even melted, into his arms.

Some people call it disaster sex, the relationships that start in wars and after natural disasters among the volunteers coping with battle, famine, refugees, after volcanos and after tsunamis or earthquakes, forest fires, hurricanes, or tornados, when the usual fabric that holds people together in their places comes apart. Others call it catastrophe, cataclysm, or calamity sex. Even apocalypse sex. It doesn’t matter what you call it. It’s what happens when two people find one another as the world is falling apart around them, as the structure and order that we rely on to live our lives with regularity, with a hope of and expectation of a meaningful future, disappears, when everything that gives a person comfort and joy – family, career, children, justice, and hope, vanishes, as natural or more often human disasters destroy what centuries and millennia of people striving together built. We need comfort. We need one another. We need healing at the level of nerves and bones and joints, of organs and blood and cells, of our secretions and of what we can taste and feel and touch, and there is nothing quite like the heat of two human bodies reflecting off one another, as we touch and stimulate in a symphony of growing arousal, attention and excitation.

The world was collapsing around Sara Jane and Darien. Democracy was under attack. The value of human life, the holiness of human life itself, was being erased by people who cared only for themselves and what they were thinking and wanting for themselves at each moment, people who gave no thought to a sustainable future, no thought to justice, and no thought to hope. You might say that Sara Jane and Darien succumbed, and took pleasure in the moment themselves, but if you think that, you’d be missing the mark. They found one another, held one another, trusted one another enough to give and take and elevate, so they were sustaining one another in a way that no one else could, when all other sustenance, all other hope was exhausted. Sexual healing, some American called it, once upon a time.

And then it was over.

Sara Jane had taken a locums posting in the north of Scotland, to give a very good GP a needed break, and she needed to go home and then go north where she could lick her wounds for a month, while she had home visits to do and while her surgery filled with old biddies with high blood pressure and glaucoma, and the worst injury she might hear about was the broken hip of an old lady who fell in the tub.

So she took the train to Krakow, walked around Krakow for a day, and then caught a low budget flight home on Ryanair.

Darien never made any sense, anyway, she told herself. Sara Jane wasn’t attracted to men. Not anymore. That’s what she told herself. She never made sense of what she felt for that nurse, so tall and blue-eyed, but that meant or seemed to mean that she needed to think about herself differently. It also wasn’t clear that she could sustain a relationship with any one person over time, or even wanted to. She was quirky and self-serving. Controlling and impulsive. Easily bored and pushy. She had no headspace for this. Nothing about it was logical. Darien didn’t fit into her life. She had constructed a life for herself. It was a chaotic life, to be sure, and was unlikely to bring her the joy or satisfaction of being loved and of loving, but it was the life she had chosen and it fit just so.

Two years passed.

Sara Jane was at a yoga retreat in Spain when she heard the news about the seven World Central Kitchen people who were killed in Gaza.

At first, it was just a news report, one more heartbreak in a heartbreaking time. Another place, another war. More bombs, missiles, drones and death. More collapsed buildings. More refugees. More mines and roadside bombs, suicide vests and more children killed indiscriminately, their numbers mounting, classified as collateral damage, as if the death of any one human being can ever be classified in a meaningful way. More grieving widows and parents. More amputated limbs, in a world that never seems to get enough of unnecessary suffering and death,

Sara Jane recoiled from what she was reading, but she put it all away. Everyone knew the Israelis were a problem, and what they were doing on the West Bank and in Gaza was wrong. But everyone had known that for years. Everyone knew that Hamas was vile and cruel and abusive to their own people, but everyone had also known that for years. Everyone knew how the Israelis would respond when attacked on October 7th. Everyone knew that there would be this human sacrifice, and that it would be for nothing, so that two sets of men could see themselves as powerful and each could maintain their control over their own little corners, and so the two warring peoples would continue to suborn tyranny, each in its own way. You rue the failures of human beings to be human, but at the end of the day, everyone is responsible for her or himself. If Israelis and Palestinians were willing to tolerate the tyrants and the extremists in their midst, they would continue to battle one another. Israel was a problem. Hamas and Islamic Jihad were problems. Everyone in England and Europe knows that. But there is nothing to be done.

And then Sara Jane saw the names.

It didn’t matter really. They, Sara Jane and Darien, were over and done. Had been over and done two years before. One and done. It was a different time and a different place. Long ago and far away. There had been no there there, not really. Disaster sex. That’s all.

There wasn’t even anyone to call.

So she finished the retreat and then came home on another Ryanair flight.

Sara Jane looked out the window as the plane took off. There was no there there. She felt numb. Somehow absent. As if this wasn’t her actual life. Her thing with Darien had been a moment, the blink of an eye, a fading shadow, in a life that itself was without meaning, that was already slipping away.

It could have been something, perhaps, if she had let it.

And yet she felt alive again, in a new way. Perhaps it was sitting in that plane, in the same airline, which herds people like cattle. Perhaps it was seeing the coast of Spain appear and then disappear as the sun touched the horizon in the western sky.

Bereft. That was how Sara Jane felt. Empty. But alive.

You do not choose how or when you will die. But you can choose how you will live.

The world is the way it is because of what we each go along with. Because of what we each tolerate. What we each forgive in others, and in ourselves.

But we can change. And when we change ourselves, we change the world.

There is no other choice, Sara Jane thought. I will change.

The plane chased the sun as it flew north and west. So, the sunset was prolonged, and Sara Jane watched the sun’s last light just as the plane landed in Manchester.

___

Many thanks to Carol Levitt for proofreading and to Brianna Benjamin for all-around help and support.

___

Please click here to receive Michael Fine’s monthly short stories and his new series, What’s Crazy in Health Care. Please invite others to join by sending them the link here.

Information about Michael’s books, stories, posts, talks and performances is available at www.MichaelFineMD.com or by clicking the link here. Join us!

___

Read more short stories by Michael Fine, go here: https://rinewstoday.com/dr-michael-fine/

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor in Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.