Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Outdoors in RI: Help keep recreation areas clean. Invasive Milfoil, trash. 2A update – Jeff Gross July 26, 2024

- Real Estate in RI: Highest-ever sale in Queen’s Grant, EG $1.25M, by Residential Properties July 26, 2024

- Homeless in RI: Gov. Newsom issues Executive Order. Remove California’s encampments. July 26, 2024

- Let the games begin. XXXIII Summer Olympics – John Cardullo July 26, 2024

- GriefSPEAK: What would you do? – Mari Dias Nardolillo July 26, 2024

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

The College Hill Study, part 2, Lost Providence – David Brussat

by David Brussat, Architecture Here and There, contributing writer

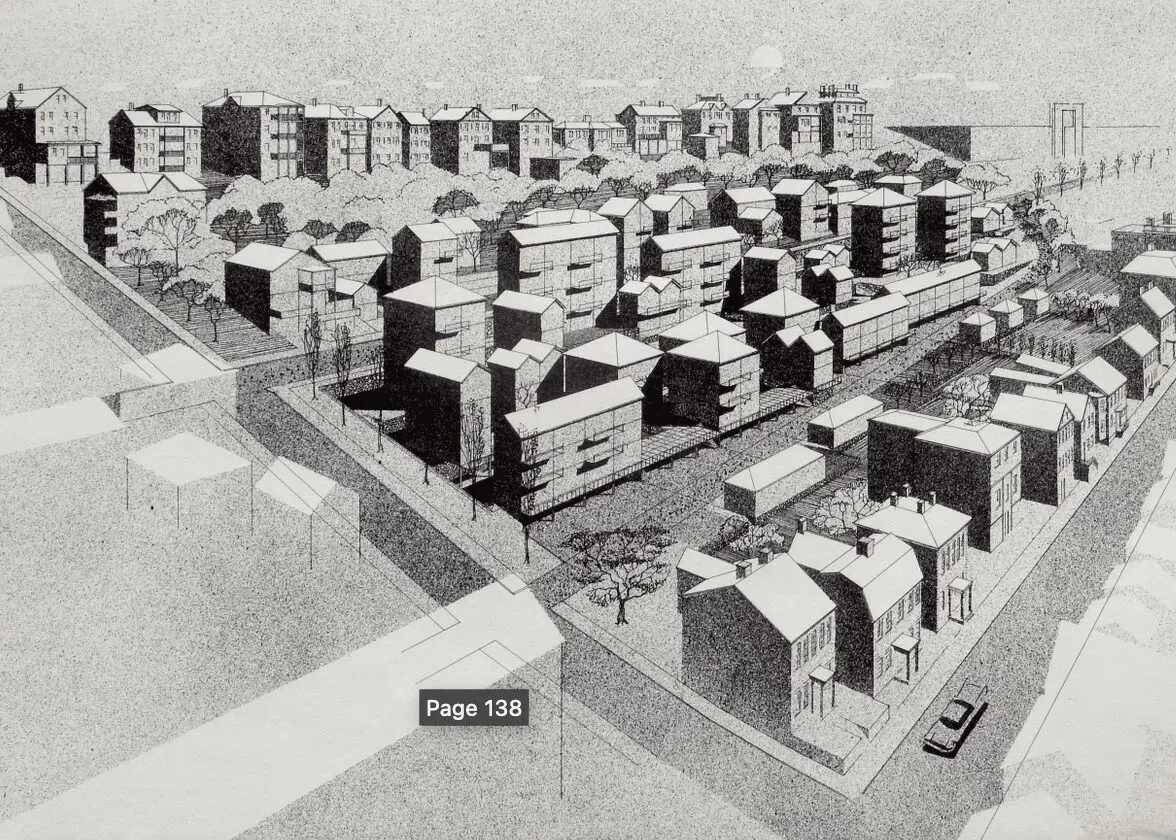

Illustration of proposed modernist infill development on College Hill. (Author’s archives)

Here is the second half of Chapter 16, “The College Hill Study,” from Lost Providence. The study’s proposals, released in 1959, would have replaced much of the fabled district’s historical houses with modernist infill, although most of the houses condemned as examples of “blight” were eminently salvageable, as history demonstrated. Many now sell for millions. Yet the study has been mischaracterized for decades to disguise its true identity as more of the failed conventional wisdom of urban renewal – also proposed simultaneously for downtown Providence and cities throughout the nation.

***

The history of extensive private investment in restoring old houses on College Hill puts the lie to claims in the College Hill study, backed by supposedly detailed analysis, that many old houses were not worth saving. Maps on pages 98 and 100 of the study show specific structures and specific areas that were judged, respectively, to be “substandard” and “slum.” That these were eventually fixed up and rose in value suggests a bias in the study’s assessment of “blight.” The language of the assessment criteria is extensively couched in terms of rehabilitating structures; it is largely left unsaid that those structures that did not rack up enough points were likely to be targeted for clearance – and replaced with structures entirely insensitive to their surroundings.

Beatrice O. “Happy” Chace led an effort to buy fifteen and, eventually, forty old houses on and near Benefit, fix up their exteriors and sell them for a song to families who would restore or renovate the interiors according to their own preferences. Others followed her lead. Antoinette Downing, even as she helped to develop the analytical tools whose use is pilloried in this chapter, advised the private preservation effort. By 1980, some $20 million had been invested in restoring about 750 old houses on College Hill, more than half of the total number of houses in the study area.

Downing and Happy Chace are the real heroes of Benefit Street and College Hill, with a supporting cast drawn from the city’s leading preservation organizations, including many members representing Rhode Island’s first families. How a plan so contrary to their belief in preservation managed to be written and adopted beggars the imagination. Eventually, under Mayor Cianci’s first administration in the mid-1970s, the municipality turned against urban renewal and toward preservation. It created, for example, a new program in the mayor’s office of community development to help building owners undo the faux façades that the downtown Providence 1970 plan and earlier municipal policies had urged or inflicted on that district.

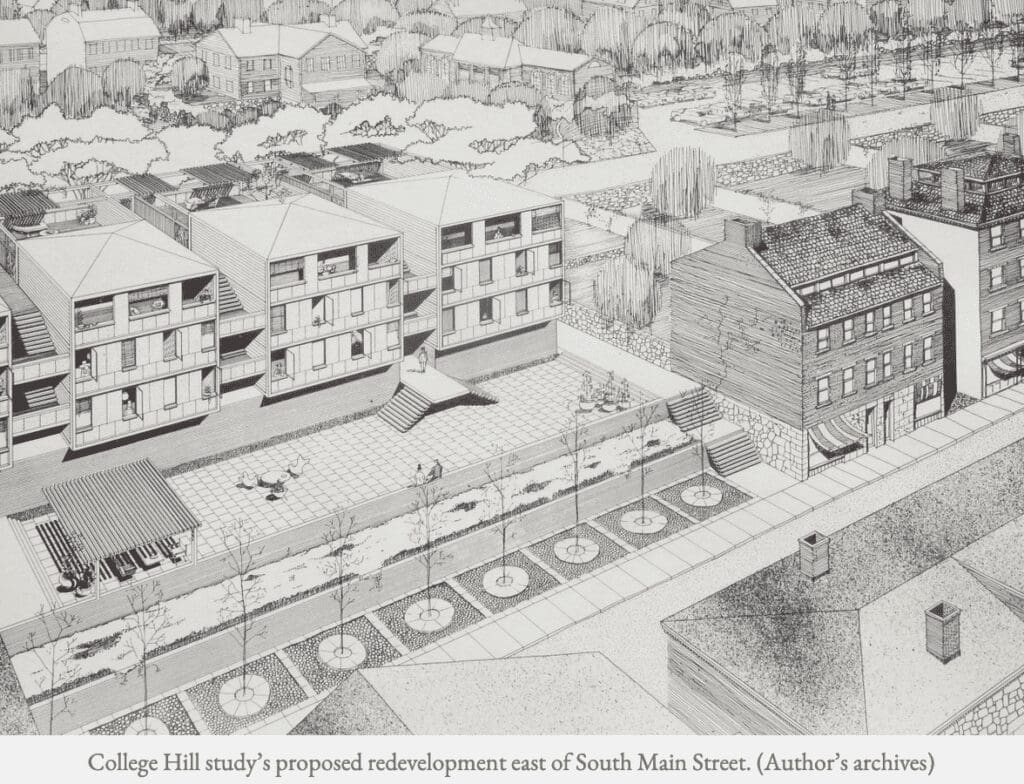

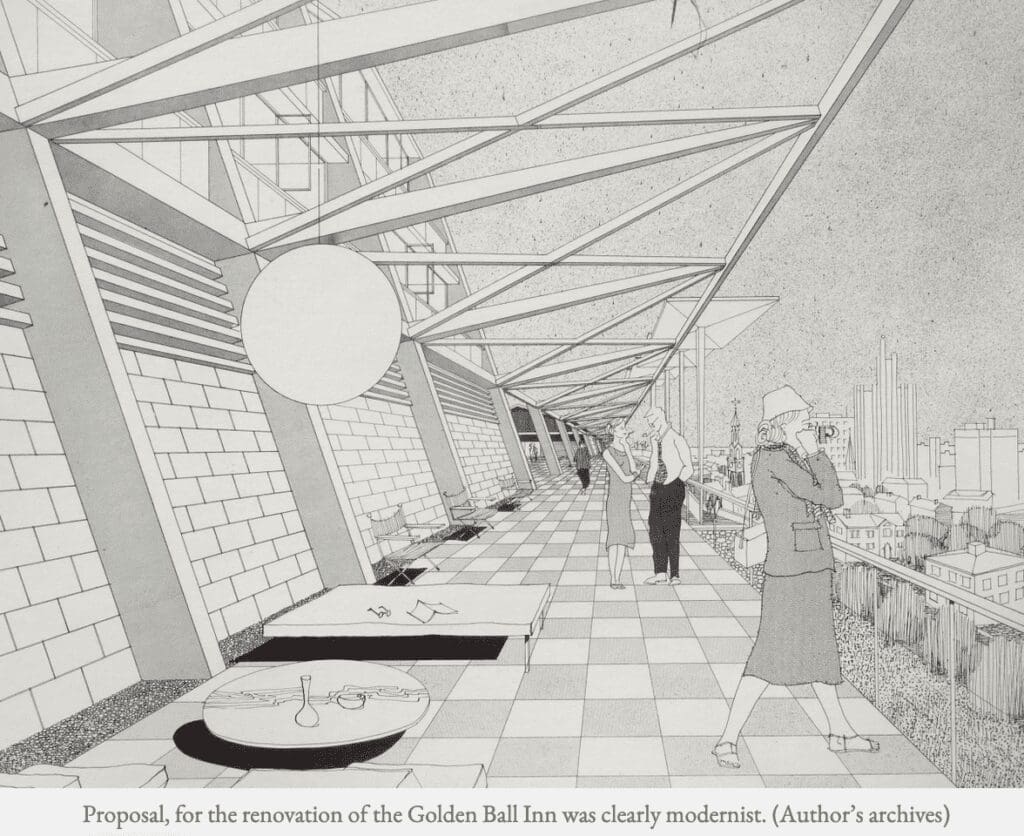

The downtown plan was coy in its textual references to the architectural shift it had in store, not seeming to mind that its illustrations let the cat out of the bag. Likewise, the College Hill study’s text was coy in describing the aesthetic shift it was recommending and equally unconcerned about illustrating it. The study’s summary points out that “the architectural designs of the planning proposals attempt to show how contemporary design can complement existing groupings of buildings of a past era.” It is difficult to reconcile the illustrations in the study with that goal. No reconciliation of old and new is shown, let alone explained or justified in words, except by naked assertion. Perhaps the closest the study comes to an attempt to justify such a goal is in a description of the South Tower planned for Benefit Street:

In the conception of this building, the project makes a break with the past in such a way that the structures of each era are clear expressions of individual integrity. (Page 148)

So the tower and its traditional neighbors express a sort of complement-by-contrast? Only in its condescension to the public’s continuing reverence for historic styles does the study abandon generalities. Regarding the scarcity of contemporary design on College Hill, the study is unable to resist thumbing its nose:

Most of the twentieth century domestic building [on College Hill] has been of mixed character with Colonial Revival predominating. Only one or two houses have been designed in the contemporary idiom. (Page 35)

Rhode Island building of the twentieth century continued in an eclectic path and in this respect is not representative of contemporary architectural concepts. (Page 38)

A few rather minor College Hill buildings have been executed in the contemporary idiom, although contemporary building modes are still suspect in conservative modern Providence. (Page 39)

A new Computing Laboratory at Brown is currently being designed by Philip Johnson. It will be the first Brown University building to reflect today’s approach to architectural concepts. (Page 70)

Get with the program, Providence! A passage from the study on page 187 reads:

Detailed studies of the structures in the area confirm the fact that College Hill does not have a concentration of any one style as is the case in many other cities that have enacted historic area controls. This fact emphasizes the validity of the statement that it makes no sense to prevent the design and construction of any one style of architecture.

And yet every style except for contemporary modernism had been excluded from recommendations by the study for new infill construction.

The passage quoted from page 187 is entirely incoherent. The fact is that the design element of the plan as a whole did not, in the eyes of the planners, need to make sense. It was assumed that there would be no critical analysis of any aesthetic judgment in the study from the design community, let alone civic leaders or the public – the latter were clearly expected to remain mute in the face of all this expert opinion. These expectations were largely borne out.

The planners’ attitudes resulted in errors of assessment. The errors fall into two main categories. First is the exclusion of houses built after 1830 from consideration as of primary or even secondary importance, as described in the “Categories of Building Priority” on page 80. This omitted many historic Victorian and revival-style buildings from the primary and secondary lists of buildings worth preservation rather than clearance. The second error is the grouping together of two necessarily separate categories of twentieth- century architecture. On page 78, a chart codes as blue all structures in the final category of architectural periods “modern: 1900 to date.” This lumps six decades’ worth of traditional buildings in a range of styles – neoclassical, eclectic, revivalist, regional, etc. – together with contemporary modernist styles, mostly of later vintage. More and more modern architecture had been popping up in Providence for three decades by the time the study was published in 1959; more and more, to be sure, but given the tut-tutting by the study’s authors, not nearly enough.

The production and public release of the College Hill study were generally coterminous with the production and release of the downtown Providence 1970 plan. Both plans embraced the conventional wisdom of their time. Both sacrificed patterns of urbanism and design that had evolved incrementally over centuries in favor of massive experimental dislocations based on untested planning and design theories that are viewed with suspicion by most people and had, by then, generally failed at every level of implementation over half a century. Both plans would have continued to deck over the Providence River.

The redevelopment proposals of both plans were abandoned with little or no acknowledgment of error. And redevelopment proposals that were implemented had minimal impact on Providence – almost all of which was detrimental to the city and its residents. But without diminishing the College Hill plan’s accomplishments outside the realms of planning and design, it has, unlike the downtown plan, a much better reputation in today’s public consciousness than it deserves.

In the early 1970s, the city sought to burnish the tourist allure of Benefit Street by bricking its sidewalks and replacing its highway-style steel cobra-head lampposts with historic posts reminiscent of gas lighting. “This is not preservation,” wrote Ada Louise Huxtable after a visit to Providence, “this is Las Vegas.” As the architecture critic of the New York Times, she was entitled to her opinion, but clearly she lacked the will to acknowledge traditional architecture’s potentially constructive role in a historic city. One naturally harks back to H.P. (“I am Providence”) Lovecraft’s letter to the editor of the Providence Journal in 1929 defending the Old Brick Row. Of the tendencies that dominated the currents of change even then, he wrote:

The side of tradition, which finds the soundest beauty in the retention of forms and proportions evolved from the continuous history of a proud old seaport, is well-nigh unrepresented; all the commentators apparently taking for granted the cruder, flashier ideal of a stridently modernized city of pompous vistas and spruce, mid-Western architectural luxury—not a haven to charm the connoisseur of richly mellow old-world lanes, but a tungsten-drenched midway to lure the hard-boiled buyer from Detroit, or a scenic flourish in deference to Seattle and Los Angeles aesthetes attuned to a futuristic Chicago.

___

To read other articles by David Brussat: https://rinewstoday.com/david-brussat-contributing-writer/

My freelance writing and editing on architecture and others addresses issues of design and culture locally and globally. I am a member of the board of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which bestowed an Arthur Ross Award on me in 2002. I work from Providence, R.I., where I live with my wife Victoria, my son Billy and our cat, Gato. If you would like to employ my writing and editing to improve your work, please email me at my consultancy, [email protected], or call (401) 351-0451