Search Posts

Recent Posts

- To Do in RI: 2-day Newport Flower Show – Authors on floral design to speak June 21, 2025

- In the News… quick recap of the week’s news 6.21.25 June 21, 2025

- Providence Art Club Prestigious National Open Juried Exhibition Begins June 21, 2025

- Burn with Kearns: “30-day Shreds” Fail the 50+ Market. What To Do. – Kevin Kearns June 21, 2025

- Rhode Island Weekend Weather for June 21/22, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 21, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

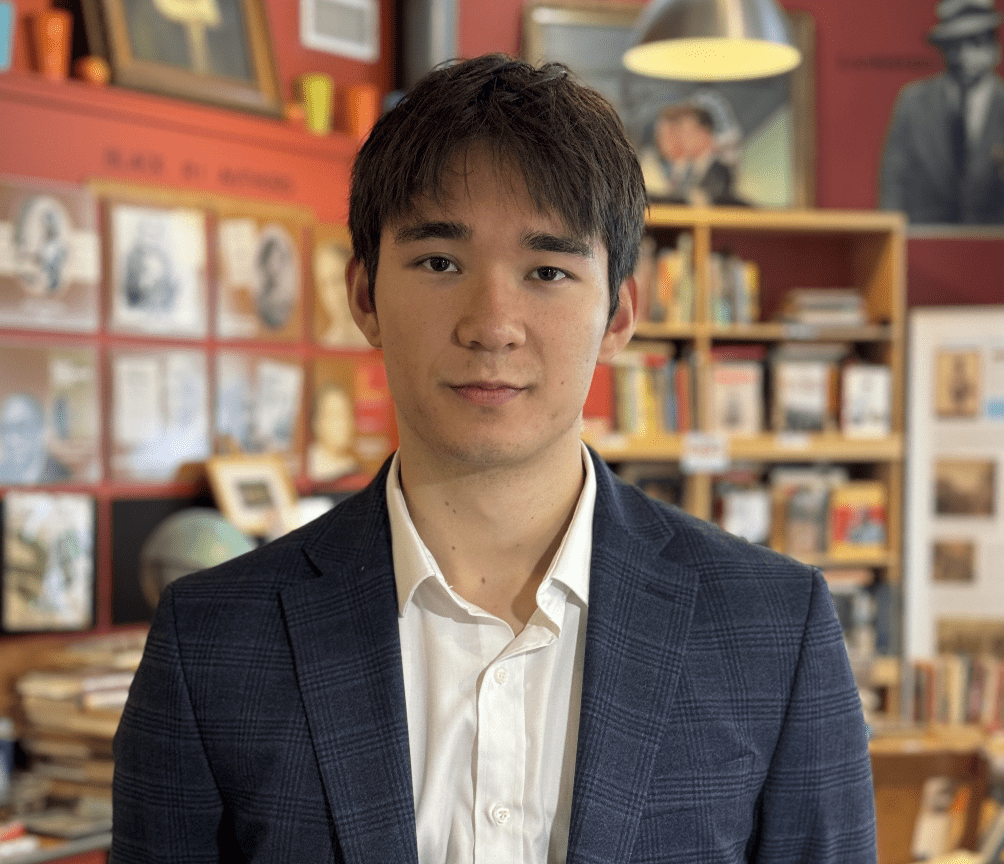

Stages of Freedom event recognizes Owen Hwang for his thesis on Black student walkout at Brown U.

Stages of Freedom, the award-winning Black non-profit, hosts a special gathering to recognize Owen Hwang on the completion of his senior thesis about the Black student walkout at Brown University in 1968. The thesis has received honors. Hwang’s history explores African American unrest over the Providence Ivy League’s failure to adapt to America’s changing racial landscape and Civil Rights laws.

The event, free and open to the public, is Friday, May 16, 5pm at the Brown University Faculty Club, 1 Bannister Street, Providence, RI. Brief remarks by Owen Hwang and Stages of Freedom co-founder Ray Rickman, will be followed by a reception.

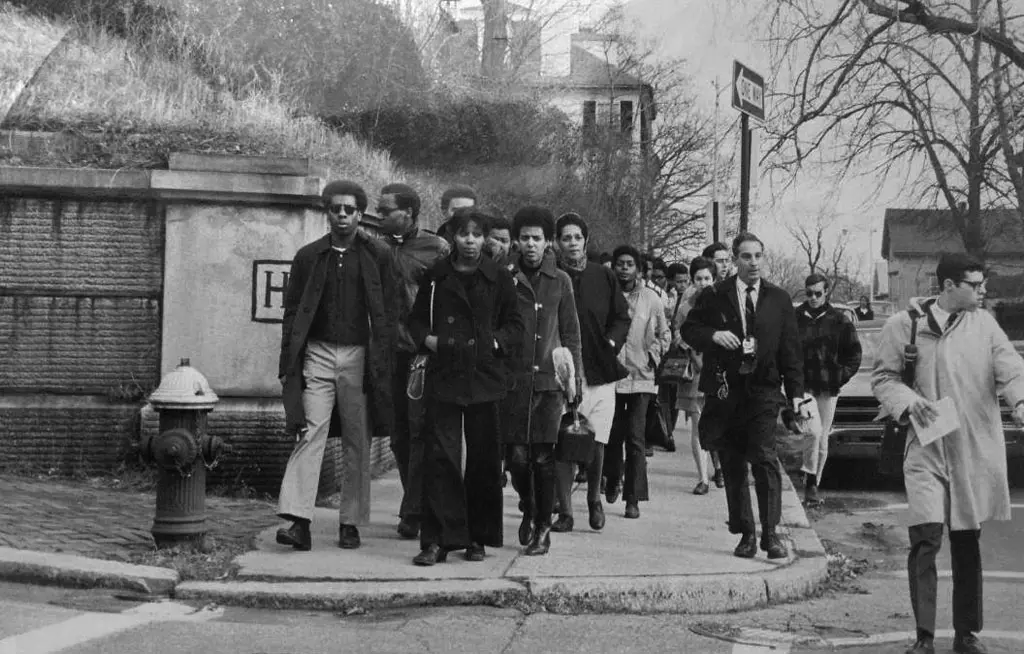

Stages of Freedom believes Hwang has written the most important Black Rhode Island document of the year. Students marched from campus to the historically Black Congdon Street Baptist Church, where they found refuge, a base of operation, and made significant connections to the wider African American community. Their courage and unity changed Brown University forever, from a narrow-minded elite institution to one that reflects a more open, just society.

The Campus Walkout That Transformed Brown University

The 1960s were a busy decade. Civil rights. Vietnam War protests. Black activism on college campuses. Counterculture. The Great Society. Assassinations and more.

The college campus protest story would be incomplete without the acknowledgment and acceptance of the significant life changing events for many people at Brown University from December 5-December 9 of 1968.

We are fortunate to learn more about this local event in the Rhode Island community because of Brown University student Owen Hwang, who I had the pleasure of interviewing recently on his years-long product as the topic of his senior year thesis.

Owen hopes to become a civil rights lawyer, and has already worked at several civil rights offices in Massachusetts and Rhode Island recently.

After encountering protests on campus after the October 2023 escalation of Israel-Palestine conflict, Owen decided to look at what history has to offer about past student protests.

Brown University, like many Ivy League colleges, was attempting to court more African American students as the Civil Rights struggle metastasized and endured into the climatic 1960s decade. However, to the very few Black students at the time (consisting only 2% of the Brown University student population), they questioned whether the efforts were tokenism or legitimate commitment to Black students.

One former student Mr. Hwang interviewed said “he did not feel he belonged at Brown or that Brown belonged to Black students…” until Ruth J. Simmons became Brown’s first Black woman president in 2001. Another student at the time said he felt he was in “survival” mode and in an environment of “total exclusion” and “alienation,” and one other account cited a “feeling of invisibility” on the mostly white campus.

Some of the critiques and grievances Black students at Brown University had concerned the lack of institutional support for African American students, the lack of student diversity featuring more classmates of Black descent, the need for more Black professors and faculty on campus, and a reform to the academic curriculum (especially history) to offer accountancy of history & memory from the Black community at large, especially in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement.

Owen tells the unique story of not just why Brown students acted-as some local writers and historians have already done-but how they acted, often led by a vibrant Afro-American Society that consisted of the Black students on campus (today it’s called the Black Student Union).

“The Black student group struggled to get the administration to take their demands seriously. The administration deferred real commitments to the demands for Black faculty and increased Black recruitment with vague promises and sending things over to committee. After the Black students concluded the admin had a lackadaisical attitude toward their demands, they walked out. For four days the students stayed in the Congdon Street Baptist Church.

Owen’s thesis argues for the centrality and symbolism of the church’s involvement in the walkout. The church, the oldest Black church in Rhode Island with a complicated history to Brown, materially and spiritually supported the students throughout the walkout.

Unlike other demonstrations at colleges like Columbia, Howard, Fisk, Tuskegee, or San Francisco State, the walkout was known for its ability to remain peaceful and “non-confrontational,” yet stringent on its demands and unbendable to compromise. The walkout movement relied on allies in the local Black church congregation on Congdon Street and longtime Black community members who saw their own neighborhoods transformed by gentrification and highway construction. Because of these developments, it caught the attention of local news using its extensive news film and photography to cover the events, and the event circulated within national newspapers like the Boston Globe and New York Times.

The walkout publicly challenged Brown to live up to its “liberal” image and commit to greater support of Black students. As a result, the president acquiesced to additional demands from activists that included the hiring of a Black admissions officer and changes to the financial aid and admissions process so more Black students could afford to apply to Brown.

The legacy is profound in its short-term success even as various demands were slow to be enacted by administration at first and featured an array of obstacles afterwards. Long term, the struggle for justice and opportunity continues in a pattern of ebbs-and-flows with setbacks to the community as they viewed it, such as the overturning of affirmative action by the Supreme Court.

Nonetheless, the Brown University walkouts of 1968 are still impactful with the ramifications being felt today. Brown’s many more Black graduates since 1968 have achieved big dreams and successes since then. In 2018, at the Black Alumni Reunion, many former students retold the stories and legacies of the 1968 student walkout as they remembered its impact on them, and their determination since then to make Brown recommit to its original promises in 1968.

All of which serves as a reminder of how change is a long-term goal that features successes and setbacks, and victories and obstacles. That is a useful lesson especially for the Providence, RI community today in “bending the arc” towards justice and equality.

Because of Owen Hwang’s diligent work and research, we are now even better informed about a crucial event in the long decade of college campus protests and Black activism.