Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Rhode Island Weather for June 15, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 15, 2025

- To honor Pawtucket Mayor Henry Kinch: A tribute to leadership and legacy June 15, 2025

- Ask Chef Walter: Summer Feast for the Palate – Chef Walter Potenza June 15, 2025

- A Greener View: Floppy Perennials, Holey Vegetables and Wet Soil Gardening – Jeff Rugg June 15, 2025

- Gimme’ Shelter: Old Bay at the Providence Animal Control Center June 15, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Lost Providence – trials and triumphs in urban planning – David Brussat

by David Brussat, Architecture Here and There, contributing writer on architecture

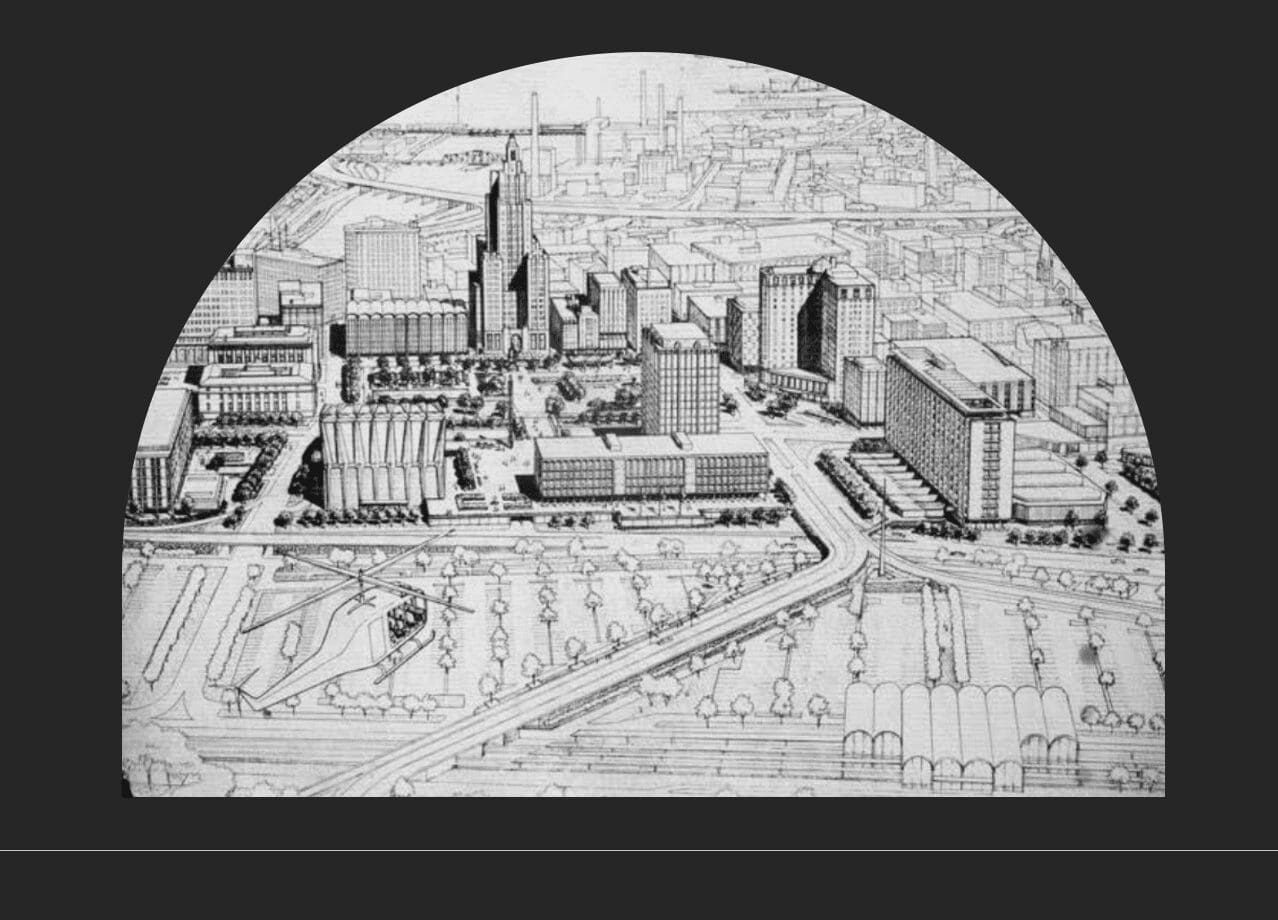

Photo: Aerial view from Downtown Providence 1970 Plan, announced in 1960 but carried out only to a very limited extent.

Five years have passed since the publication of Lost Providence, so there is no better time than now to re-introduce my book to readers of my blog. In 2015, the History Press asked me to expand one of my last Providence Journal columns, “Providence’s 10 best lost buildings,” into a book. I persuaded my editor to let me add 11 chapters on economic development projects, whether “lost” or completed, as far back as the early 19th century. Several chapters from the second half of the book, broken up into smaller bits, will serve to emphasize that traditional architecture served Providence well for three centuries and should be embraced to solve problems the city faces in its fourth century, which begins only 14 years from now.

***

Chapter 15

Downtown Providence 1970 Plan

This account of Providence’s storied architectural history has already hinted strongly that even before the 1950s, mistakes were made. Decking over the rivers between downtown and College Hill was one error. Neglecting the void between the State House and downtown was another. Decisions to route a pair of federal highways through the city so as to cut off downtown from districts to its north, west and south are today considered a serious error by almost all sensible people. However, the City Plan Commission had proposed, in the early 1940s, to run a highway right up the middle of the Providence River between the old East Side and West Side. A 1947 report written for the state department of public works by the Charles A. Maguire & Associates engineering firm describes the plan:

A part of the [option] 6 scheme considers the use of the open area of the Providence River, where a depressed highway would be built from Fox Point northerly through the present congested area at Crawford Street, Memorial Square and along the general line of Canal Street. … The present Providence River, often called an open sewer, being enclosed in conduits, would be eliminated from view, greatly beautifying the City.

The “Up Yours with a Concrete Hose” highway option was rejected as too expensive, a rejection that is easy to applaud in retrospect. In the following decade, the “eradication of history as a development strategy” urban removal plan picked up where “Up Yours” left off.

The Downtown Providence 1970 plan, announced in May 1960, looked forward a decade, but for inspiration it looked backward a decade, to the period when an already entrenched conventional wisdom in architecture and planning dictated a new master plan for downtown that directly and aggressively challenged the validity of Providence’s architectural heritage. Most of this plan for downtown was not carried through, another decision whose wisdom is said to reside in retrospect. Today it is hard to imagine city officials taking this plan in stride. It should have been no more imaginable at the moment of its announcement than it is today.

“Downtown Providence 1970: A Demonstration of Citizen Participation in Comprehensive Planning” describes a project announced after three years of research, begun in 1957, sponsored by the City Plan Commission and backed by the U.S. Urban Renewal Administration. The project study recognized that downtown had become run-down and proposed to spiff it up with new design that supposedly respected existing architecture. At the conclusion of the study program, its “Citizen Task Forces” were, the study’s foreword asserts, “assured that this plan is tailor-made for their City.”

The wording leaves it unclear whether citizens were assured – or merely informed that they were assured.

In their comprehensive book on The Renaissance City, Francis Leazes and Mark Motte describe the 1970 plan much more straightforwardly than what is stated anywhere in the plan itself. They write:

At the heart of Downtown Providence 1970 was a classic, 1950s-style urban renewal: wholesale redevelopment of the urban core by demolition of the historic commercial center, including the French Revival-style Providence City Hall. The new central business district would become a single-use environment focused on office development, punctuated by pedestrian zones, parking lots, large public spaces, a heliport, and numerous Le Corbusier-inspired modernist office and residential towers linked by multilevel walkways, plazas and acres of satellite parking lots.

Le Corbusier is often considered the founding theorist of modern architecture and is today most widely known for his 1925 plan to demolish central Paris. Massive concrete public housing projects for the poor are considered his major legacy. They degrade cities around the world. The study’s summary states:

Beauty is as important as any of the other considerations that we apply to the rebuilding of the city. Without beauty we cannot evoke the civic pride which assures continued interest and participation by the community. … Careful placement of [new] buildings where they can be seen from afar will lend visual identity to the total Plan. Historic continuity has been emphasized in special treatment for great buildings of the past. … It is concluded that a highly coordinated professional effort is needed, if we are to turn the tide of urban ugliness and make Downtown once again a place of beauty.

“Words, words, words! I’m so sick of words!,” Eliza Doolittle’s line from My Fair Lady leaps to mind.

The introduction to the study’s section “Design in the City” opens with a seemingly introspective set of passages regarding the role of aesthetics in the sensibility of cities. None of it makes any sense in light of what the plan proposes. The section following the introduction, entitled “A New Direction,” states:

If we are to realize the potential of our abundant economy and create a community of abundant beauty, we must make a concerted effort in this period of widespread urban redevelopment to apply new and truly enlightened principles of planning and design. These new principles, embodied in what Morton Hoppenfeld has called “a higher order of design,” are primarily concerned with the relationship of one building to another, and to the natural and man-made environment, and have evolved from a study of the ways in which man uses and perceives his world.

Apparently, the importance of what a building looks like, in and of itself, does not count for much compared with its relationship to other buildings. At no place in the study is there any attempt to explain or defend or even admit to the existence of the plan’s ambitious, indeed radical, conception of how the appearance of the city must change. It seemed entirely sufficient to declare that the changes will “apply new and truly enlightened principles of planning and design” and “what Morton Hoppenfeld has called ‘a higher order of design.’” They are not further described, explained or justified. And who was this Hoppenfeld? The plan does not say. It was just as Tom Wolfe put it in his 1981 bestseller From Bauhaus to Our House. Describing the sly manner by which European modernists who fled Nazi Germany overturned tradition in postwar American architecture, Wolfe writes, “All architecture became non-bourgeois architecture, although the concept itself was left discreetly unexpressed, as it were.”

Hoppenfeld, by the way, was “a young visionary,” an urban planner who “shared a desire to create new kinds of American communities,” according to a 2001 book, Suburban Alchemy: 1960s New Towns and the Transformation of the American Dream. In 1960, shortly after he was cited in the 1970 plan, he was hired by James Rouse, a developer of new towns such as Reston, Virginia, and Columbia, Maryland, in suburban Washington. In the 1980s, after a career designing new towns and “destination centers” such as Boston’s Faneuil Hall Market, Rouse visited Providence and urged the city to open up its rivers.

Again, the 1970 plan says virtually nothing about what the “higher order of design” intended for downtown would look like, but it certainly is not shy about showing it off in the plan’s architectural renderings. Such drawings were not intended to represent the final designs of buildings but rather to give a general sense of their likely appearance. When the plan was announced in May 1960, the city’s two television stations gave the event wall-to-wall coverage. Illustrations from the plan were printed in the Providence Journal.

The citizens of Providence could not claim to be ignorant of what was coming down the tracks.

***

Stay tuned for the second half of the 15th chapter, and for subsequent chapters in Part II of Lost Providence.

___

To read other articles by David Brussat: https://rinewstoday.com/david-brussat-contributing-writer/

My freelance writing and editing on architecture and others addresses issues of design and culture locally and globally. I am a member of the board of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which bestowed an Arthur Ross Award on me in 2002. I work from Providence, R.I., where I live with my wife Victoria, my son Billy and our cat, Gato. If you would like to employ my writing and editing to improve your work, please email me at my consultancy, dbrussat@gmail.com, or call (401) 351-0451