Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Real Estate in RI: Seaside waterfront communities are all the rage. Who’s buying – Emilio DiSpirito June 6, 2025

- Outdoors in RI: 2A votes, Charter Yachts, active summer programs, garden tours, aquatic weeds… June 6, 2025

- All About Home Care, with two Rhode Island locations, closing after 22 years in business June 6, 2025

- GriefSPEAK: Angel wings with footprints – Mari Nardolillo Dias June 6, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 6, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 6, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

LOST Providence: The Downcity Plan – we need developers that say “yes”! – David Brussat

by David Brussat, Architecture Here and There, contributing writer

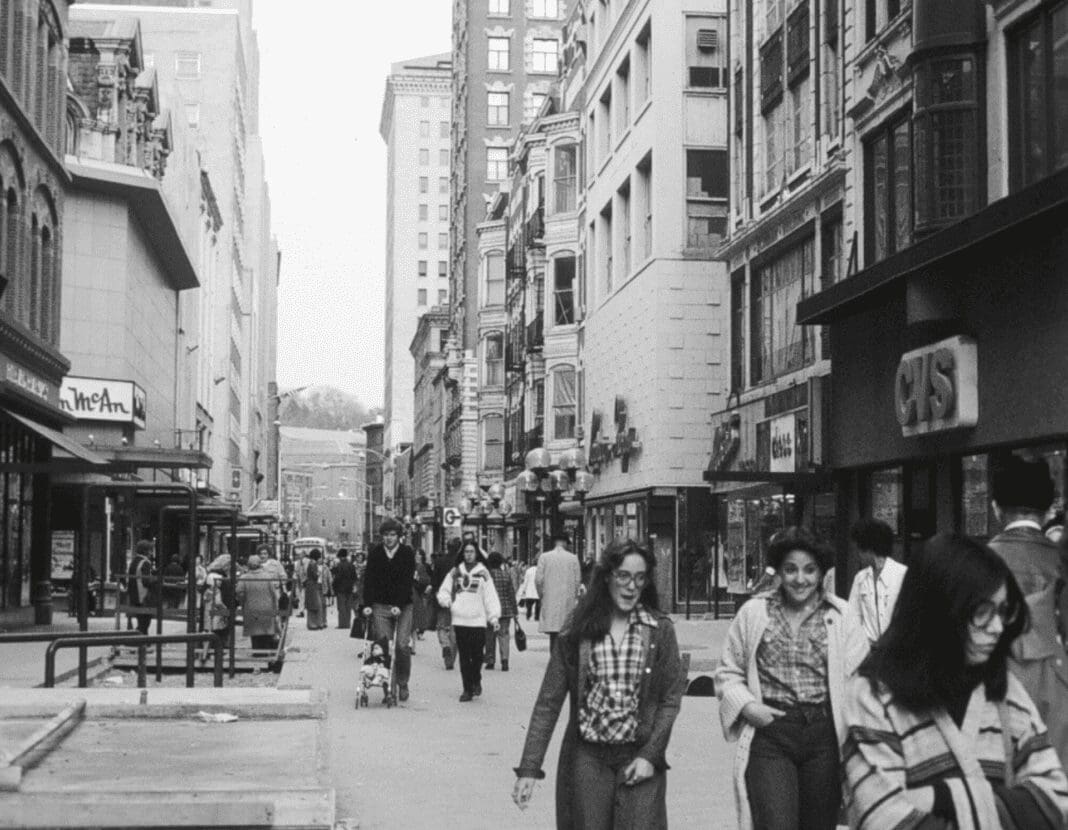

Westminster Street in 1978, pedestrianized and known as the Westminster Mall, from the almost entirely unrealized and totally discredited Downtown 1970 Plan. Except for the noon hour, it was usually empty. Note the faux modernist siding on ground floors, including, at far right, the sheathing on the Old Providence Journal Building, applied in the 1950s prior to the 1970 Plan.

Editor’s note: This is the first half of Chapter 22, “The Downcity Plan,” from the book Lost Providence, published in 2017. (I accidentally referred to this post initially as the “bottom half” of Chapter 22. I regret the confusion that must have caused some readers.)

***

Economist Richard Florida’s 2002 book The Rise of the Creative Class revealed, as if it required exposure (which in fact it actually did), that people want to live and work in places with character. Of Providence, he wrote:

Many members of the Creative Class also want to have a hand in actively shaping the quality of place of their communities. When I addressed a high-level downtown revitalization group in Providence, Rhode Island, in the fall of 2001, a thirty-something professional captured the essence of this when he said: “My friends and I came to Providence because it already has the authenticity that we like – its established neighborhoods, historic architecture and ethnic mix.” He then implored the city leaders to make these qualities the basis of their revitalization efforts and to do so in ways that actively harness the energy of him and his peers.

Florida may well have been referring to Andrés Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, whose firm, DPZ, worked with Providence native Arnold “Buff” Chace and his firm Cornish Associates to revitalize downtown. By the early 2000s, they had hosted brainstorming sessions in Providence called “charrettes” for a decade. Duany had helped to found the Congress for the New Urbanism in 1993. The CNU organizes a movement that has updated concepts that had lain fallow in America since before World War II, concepts that might as well be called “the old urbanism.” The new communities built under the banner of the New Urbanism often require long negotiation with local authorities, because suburban zoning laws across the nation typically bar new enclaves with narrow streets on short blocks with a variety of housing types within walking distance of shopping, such as corner groceries and small stores on the ground floors of residential structures or granny flats above garages in the rear.

Unrealized proposal from the Downcity Plan for park across Westminster Street from the Shepard Building, once a department store, now the downtown branch of URI. (Drawing by Randall Imai)

Duany first worked with Buff Chace and his Cornish development team on Mashpee Commons, in the town of Mashpee on Cape Cod. Beginning in 1986, Chace sought to turn a typical suburban shopping plaza into a traditional town center. By the early 1990s, DPZ had joined the project, inviting Chace onto the board of the CNU. In 1991, Chace purchased several underused buildings in downtown Providence – he recalls first checking them out with his seven-year-old twins, his daughter saying, “Daddy, why don’t you do something about it?” He then sought DPZ’s assistance in their redevelopment – a boon, as DPZ and the CNU had sought to broaden their base of mostly suburban greenfield development to include urban infill projects designed to revitalize city centers. After a series of charrettes beginning in 1992, DPZ and Cornish produced The Downcity Plan, followed in 1994 by the Downcity Project Implementation Plan.

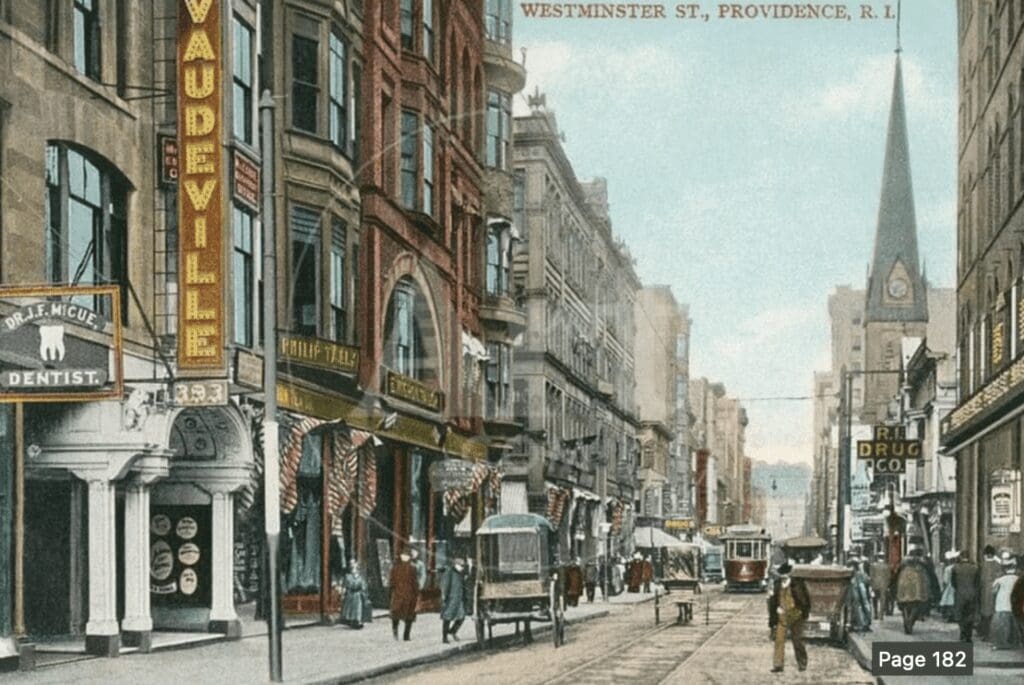

Postcard view of Westminster Street, circa 1890. (postcard art.com)

“Downcity?” Glad you asked. Duany says he heard the term from Antoinette Downing, the preservationist leader who was still going strong when a real plan to save downtown was finally afoot. Back in the day, families often used the term to refer to an activity rather than to a place. To “go down city” was akin to “let’s go shopping.” Some troublemakers sandbagged the term as a working-class signifier, asserting that no one on fashionable College Hill ever used it. Duany nonetheless picked it up, supplied it with an initial cap, turned it into a proper noun and applied it to the city’s old retail quarter between Dorrance, Weybosset, Empire and Fountain, which was the focus of his plan.

The name was an effective rebranding of the shopping district, but eventually Mayor Cianci started misusing it as a synonym for downtown, a solecism that spread like kudzu. By 2004, following yet another charrette, even the final downcity report itself uses downcity and downtown interchangeably, often omitting the latter entirely. When others started to upper-case the c in the middle without even adding a space – DownCity – it was the last straw for many who had long defended the word’s use.

Nomenclatural niceties notwithstanding, Duany summarized his plan in a 1992 report called “Downcity Providence: Master Plan for a Special Time,” which he recapitulated live for an audience at the Lederer Theater, home of Trinity Rep. In his patented speaking style of sarcastic good humor, he deplored the big projects such as the Rhode Island Convention Center as “dinosaurs” that must be countered with many “chipmunks” – small projects scattered around downtown. And he pointed out that while “no single building downtown is of the highest quality,” there are streets worthy of London and Boston. There is wonderful detail and innovative, vigorous architecture. … The only thing you could have done better would have been to do nothing at all. A 1939 aerial photograph of Providence is heart-breaking. The urban fabric it shows is exceptionally continuous. Its geometries are elegant. The streets get narrower and wider in subtle, picturesque ways.

Top: Drawing by Randall Imai of the Wilkinson Building (1900), O’Gorman Building (1925, Burgess Building (1870) and Alice Building (1898), on Westminster Street, all redeveloped by DPZ and Cornish. (Author’s archives). Below: Those same buildings today. (Photo by author)

He notes that Westminster Street especially boasts a perfect ratio of building height to street width: its low- and mid-rise commercial buildings along its narrow pavement provide excellent “enclosure,” creating, with its delicate canopy of trees, a human-scaled corridor of the highest order. This was plain to see even before the removal of faux façades kicked into high gear on Westminster. Downtown’s quirky street pattern raised the syncopation of its grid to an art form. Streets getting “narrower and wider in subtle, picturesque ways” clearly refers to Weybosset Street. Its curvature recalls the sensuality of a woman of pulchritude lying on her side – even after Weybosset’s well-turned feet were sliced off at the ankles by the Downtown Providence 1970 plan.

***

The next installment of this series will reprint the bottom half of Chapter 22 from Lost Providence. What follows below are a series of photos of the Downcity district in downtown Providence, starting with Weybosset Street and concluding with several photos of Westminster Street. The second to the last picture shows the beginning of Weybosset Street at the head of Westminster Street, where the two streets meet near the Providence River. The Turk’s Head Building can be seen at this junction. The final photograph includes my wife Victoria and son Billy in the courtyard of the Hotel Providence.

___

To read other articles by David Brussat: https://rinewstoday.com/david-brussat-contributing-writer/

My freelance writing and editing on architecture and others addresses issues of design and culture locally and globally. I am a member of the board of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which bestowed an Arthur Ross Award on me in 2002. I work from Providence, R.I., where I live with my wife Victoria, my son Billy and our cat, Gato. If you would like to employ my writing and editing to improve your work, please email me at my consultancy, dbrussat@gmail.com, or call (401) 351-0451.