Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Providence Delivers Summer Fun: Food, Water Play & Activities June 20, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 20, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 20, 2025

- Outdoors in RI: Time to Seastreak – Vets Access – Invasive Alerts – Clays 4 Charity at The Preserve – 2A TODAY June 20, 2025

- GriefSPEAK: Kill Switch – Mari Nardolillo Dias June 20, 2025

- Dr. Rosemary Costigan Named President of Community College of Rhode Island June 19, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

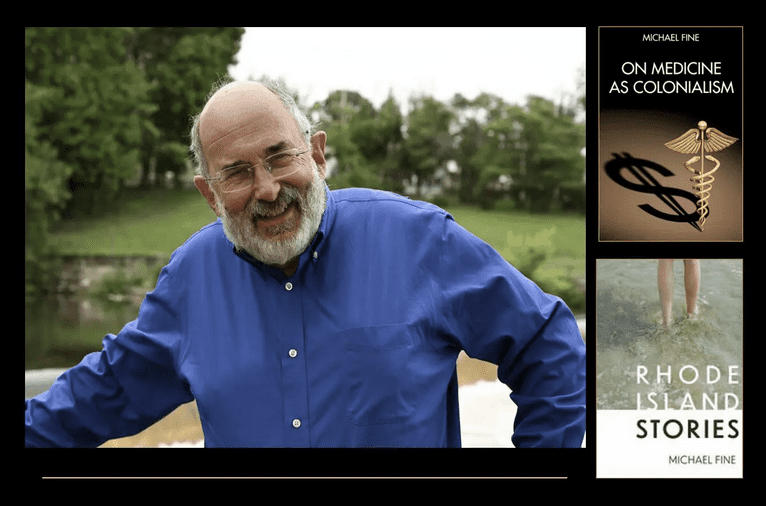

In The Tunnels: A short story by Michael Fine

By Michael Fine, contributing writer

© 2024 Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

Cold. Dark. And damp.

But we were ready.

They took the bait. We were prepared.

The tunnels were wired and mapped. And booby-trapped. The booby traps were carefully laid and could be set electronically, so they could be triggered from far off at a moment’s notice.

We have pumps and drainage – something you don’t think about when you first dig tunnels. You don’t think about the way water courses through the earth the way blood courses through the veins of women and men. You have to pump out gallons and gallons of water a day. To say nothing of human waste and the need to dispose of that waste.

But if you are clever, you build cisterns to catch the water, and that water sustains you when you are stuck inside. The waste is gathered in barrels and those barrels are transported on hand trucks down the long corridors, to be hoisted to the surface and dumped by hand in the fields at night.

It smells in the tunnels. You smell the sweat, the sewage in those barrels, the stink of the oils and sweat on human skin that you can almost taste, all of that just sits in the dank air, lives in your nostrils, and is absorbed by your eyeballs as you walk from place to place in this narrow enclosed space, fifty meters underground, where living humans were never meant to be.

We had food, of course. We stockpiled that food for years, getting ready. Food, water, clothing, even medical supplies. We have sleeping rooms, kitchens and storerooms dug out of places where there was compacted earth instead of stone, in the seams that could be made to crumble with a pickaxe. If you’ve never been below the earth, you don’t see how the earth itself is made – seams of granite and shale, which must be blasted if you are going to tunnel through them, interspaced with sandstone, gravel, clay, silt, limestone, chalk, mudstone and dolostone, all relatively easy to dig through and extract — the earth into which we’ve dug rooms — command centers, barracks, sleeping rooms, kitchens, holding cells, which can be transformed into an operating room or a hospital ward or a morgue at a moment’s notice.

We poured and reinforced the concrete for the ceilings and walls to prevent collapse.

What you don’t think about is the cold and the damp. The temperature of the earth at fifty feet down is fifty-five degrees. The air is moist and heavy. Ventilation systems blow air from the surface so there is always a breeze, a cold wind. But that air is never sweet, never clean or clear. It smells of sweat and human excrement, however faintly, the smell of anger and of fear, the stink of resignation. And it carries the distant flavor of mold and of dead flesh from the bodies wrapped in white plastic and stacked in distant rooms with doors that are closed and locked, the bodies stacked like plates in a closet. Yes, like cordwood. They don’t know who has lived and who has died. So those bodies protect us.

You remember the gloom and the smell more than the darkness.

The best one can say of the air is that it is not poisoned, though if the ventilators stop running and the air stops moving, poisonous gases will accumulate and will either explode or will poison us all.

There are canaries in cages every one-hundred meters, to tell if the air has become toxic. If the birds die, we tell the humans here to flee. The strangest thing, of course, is that the canaries sing, even underground, even without natural light. Their songs echo strangely in the dead air, echo against the cement walls and curved ceilings, echo off the sand floor, the blown-in air carrying their songs away or toward you, depending on where you are standing and which bird is singing, or which bird is still alive.

So we are cold and damp and it is dark, and people shuffle from place to place, some armed to the teeth, others moving from place to place underground because it is the only way to move safely, one man’s hand on the shoulder of the man in front. Others with their hands zip-tied behind them. The light bulbs provide dim light, just enough to see by, and the canaries sing. This is our life.

The woman did not know her place. She acted like she had no idea where she was, what the actual circumstances were, or who she was talking to. They are like that. They think their lives matter. All of them. People without humility. People who do not know God, regardless of what they say or think about themselves. They think their one life – their one miserable, solitary, selfish life – matters, and that we should all bow down to them. They know nothing of the truth, nothing about what is holy, and less about heaven.

“When are you going to get me out of this miserable pit?” the woman said.

I had no idea whether it was morning or night. About the month. Barely about the year. You do not remember the greenness of trees or the smell of the sea, after a while. No memory of the cool breezes which blow in from the coast just after dark. No, that is not true. I remembered that there were cool breezes after nightfall. But I did not remember what that wind feels like against the skin, about what it is like to have a wind that can dry the sweat.

She was a worm. Her skin was wax. Her hair was something like brown but it was thin and lifeless, brown grass that had dried in a drought. Uncovered. A whore. An infidel. Dull eyes. Stooped over, her hands tied behind her back. Clothing dusty. A filthy purple sweatshirt with the name of a sports team on the front and back, and gray pajama pants now stained brown and dirt encrusted.

“You are a worm,” I said. “An insect. Insignificant. I do not speak to insects. I catch them in midair, crush them, and then flick them away.”

“You are a dead man walking,” she said. “You understand nothing. Nothing. You have no history. No ability. No capacity. No hope.”

“I spit on you,” I said. But I didn’t spit. “You are not deserving of my spittle.”

“The first ones now will later be last,” she said. “That that goes around comes around.”

“Those are my words,” I said. “That is my life. You have no right to think that. To believe it. To believe that anticipates your own destruction, you and all of them, everyone like you, all of your family and your entire accursed nation. We won’t even bury you. We’ll leave you to rot in the hot sun.”

And then somehow, we both smiled. It was bitter, that smile. It was disrespect. It was hatred.

He was just a man, nothing more, nothing less but there was something familiar about him. A small man. Slight. Hunched over because we were in a tunnel and the low ceiling makes you want to hunch over, even when there is room to stand. The pale electric light bulbs every few feet flickered. The cold endless breeze made my back cold and the hair on my arms stand up, even though I was now used to the cold. The moist air of the tunnels made me sweat, even though it was cold and I was chilled, and the tunnel stank — mold, sweat, rot and death. You go into the earth in a pine box after you die, to rot and rejoin the earth. But you don’t belong in the earth while you are alive. It’s a living death here. No sleep. Worse than purgatory.

We smiled together. It was a reflex.

“You better run,” I said.

“From you?” he said.

“From us. We will find you. They will find you. You cannot escape. You are all dead men walking.”

“I know you all better than you know yourselves,” he said. “You will collapse. It has happened before. It will happen again. You are corrupt, inside, and the corruption eats at you. Self before soul. You know the soul a little. You have tasted it. But you are too weak to act from the greatest good. Each time, you become corrupt and lose focus. Each time you are seduced and fall because of that corruption, seduced by your uncontrolled lusts. You never learn from your own history.”

“Like you do?” I said. “We govern ourselves badly. You never learned to govern at all, in the modern world. You struggle with the same corruption we do. And sacrifice one another, in the service of a hallucination, a fable, a dream. Who is just? He who honors all men. And women. Equally. Something you can’t imagine.”

“Hah! It is, who is wise? He who learns from all men. There it is. You don’t know your own sources. You are weak, every single one of you.”

“You are stuck in the past. We invent the future. We know the past. But we also dream.”

“Human beings don’t change. Your dreams are mirages. God is all-knowing. Omnipresent. You put your faith in airplanes, in missile defense systems, in electronic surveillance. We believe only in God, And in one another. Brothers. And sisters too.”

Where have I met this man before? I wondered.

Then the bombs began to fall.

Being bombed that deep underground is unlike being bombed above ground. Unlike their rockets falling. Rockets and bombs that fall above ground bring a special horror. They are fire and brimstone. Piercing screams of the bombs falling or the rockets shrieking through the air, then the thud as they hit the ground, then fire and smoke and the air sizzling with shrapnel. The force of the blasts pulse through you. They snap your head back or throw you down or throw you against a wall when the concussion wave hits. You know you can and must run but it is not clear you can hide, because the rockets and bombs fall all around you and the earth quakes, buildings fall, fire and smoke are everywhere, and the air which is impossible to breath chokes you with the stink of burned plastic and charred flesh, which burns your eyes and nose and tongue and the roof of your mouth and your lungs as you breath it in even as you try not to breathe. You think a vengeful God is walking there, and has been infuriated, because it makes no sense for men to do this to men.

Underground is different. The earth shakes from above, dust shaking from between the reinforced concrete sections which make the roof of the tunnels. The lights flicker and sometimes go out. Sometimes portions of the tunnel walls collapse. No fire though, and no shrapnel. No whistling of bombs and metal through the air. No blast wave. Just thunderous quaking in what is otherwise silence, and the fear of being buried alive.

And so the walls caved in that day. Not with thunder. Not with lightning. There was no explosion. And no fire. Just a thud and a hiss as some of the curved concrete ceiling sections gave way. The lights in that section flickered for an instant and then gave out. I expected that he would flee, that he would leave us behind to be buried alive while he and the others like him skittered to another section, dancing in front of our bombs and guns and the final accountability that comes to all like him, and all of us, at the end of the day.

But I was not so lucky. Instead, they took us with them, shoving us in front of them, their guns in our backs, our hands bound behind us so there was nothing to break a fall if one of us stumbled. They didn’t know and we didn’t know who waited in the tunnels before us. So they were hedging our bets.

The distant thunder got closer. The walls shook. More lights went out.

They wore headlamps and that weak light lit our way.

They didn’t hurry at first. Their retreat was deliberate, planned and rehearsed. Our long shadows made it impossible to see the ground before us. When one of us stumbled into one of the tunnel walls or fell they cursed all of us as they wrenched that one to their feet and thrust their guns deeper into our backs. The breeze stopped blowing.

“Move!” he said, through clenched teeth. He didn’t want me or anyone else to know what he felt, which was fear.

But I felt no fear. Not now. My life was over and I knew that. I had known it for all these months, during which I had lost track of time. Perhaps we will lead them to their deaths. That was what I had to hope for. That was what my life had become.

The two images that I had as I scurried across the sand floor, in the darkness, was of a burning bush, and of a man kneeling over a boy who was bound and gagged on a funeral pyre, holding a knife at the boy’s throat. How inappropriate, I thought. Where is the voice out of the fire now? Where is the angel who comes to spare our lives, who comes to still the knife, who will give us the ram struggling in a thicket to sacrifice, so we stop sacrificing one another?

And suddenly I knew who he was, and where I knew him from. He was the man looking at that burning bush. And at the same time, he was the man with his knee on the boy’s chest, his hand holding the knife that was quivering over the boy’s neck. As we are the life force and the destroyer, all at once. The hope and the fear inside us all. The light and the darkness, swirling around one another. One people, despite how we tear one another apart. With one God, despite our inability to see or to listen. To one another or to God. Despite our insanity.

Then the distant thunder was in front of us as the earth shook. A thud and a hiss. The tunnel collapsed in front of us.

And then there was no place to run.

It was cold. Dark. And damp.

None of us are ever ready for the miracle of our existence, for our failures, or for death.

___

Many thanks to Carol Levitt for proofreading, to Lauren Hall for all-around help and support.

Please click here to receive Michael Fine’s monthly short stories and his new series, What’s Crazy in Health Care. Please invite others to join by sending them the link here.

Information about Michael’s books, stories, posts, talks and performances is available at www.MichaelFineMD.com or by clicking the link here. Join us!

Read more short stories by Michael Fine, go here: https://rinewstoday.com/dr-michael-fine/

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor in Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.