Search Posts

Recent Posts

- U.S. Carries Out Limited Strike on Iran’s Known Nuclear Sites (Updates) June 22, 2025

- A Greener View: E. Coli vs. Vegetables, and Your Garden – Jeff Rugg June 22, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 22, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 22, 2025

- Ask Chef Walter: The Art and Science of Baking – Chef Walter Potenza June 22, 2025

- Gimme’ Shelter: Aurora is waiting for a home at the Providence Animal Control Center June 22, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

How to read a Supreme Court case: 10 tips for non-lawyers – Rhode Island Current

by Ilisabeth S. Bornstein, for the Rhode Island Current

Reprinted with permissions from the Rhode Island Current

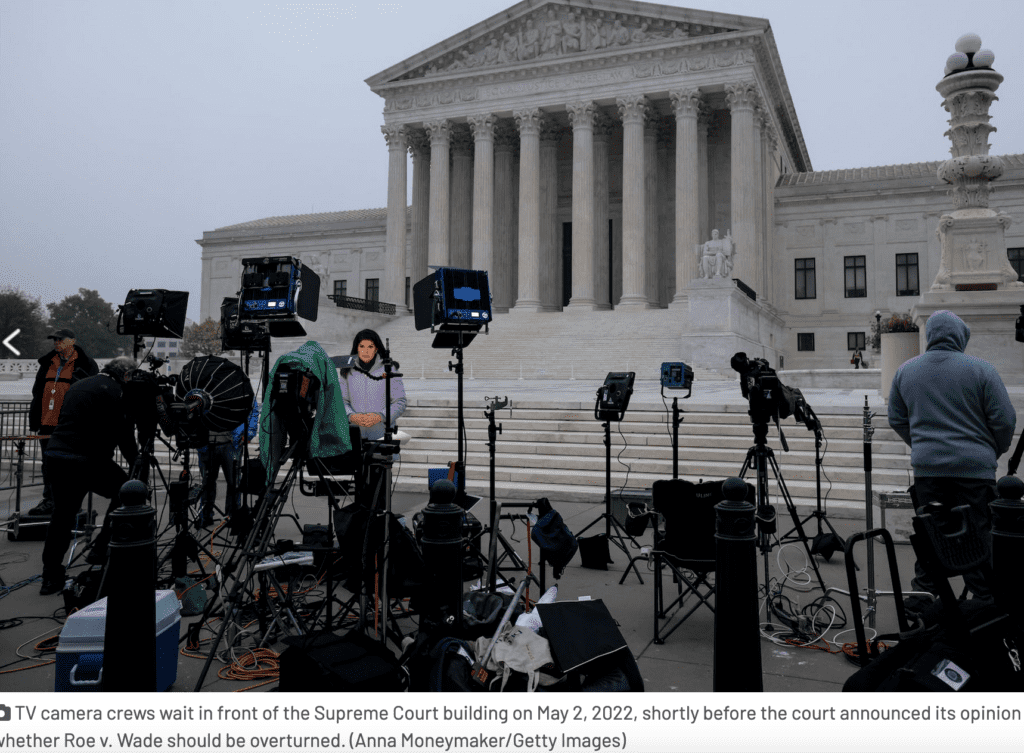

From gun rights to the availability of the abortion pill to at least one – and possibly a second – constitutional case involving former President Donald Trump, the U.S. Supreme Court is considering cases this term that may result in momentous decisions in 2024.

If you follow news coverage of these and other cases, you may want to read the Supreme Court decisions for yourself to fully understand what was decided, why and how. But when you read a Supreme Court case for the first time, the legal language, unique formatting and structure can be daunting, like looking at a giant rock face and not having any clue about how you climb to the top.

I have taught law to undergraduates for the past 12 years, so I am sympathetic to the nonlawyer’s plight. Here are some techniques I teach my students to help them break a Supreme Court opinion into digestible parts. They should help you begin to understand what was decided, why and how in the important cases being considered by the court this term.

Where do I find the case?

First, make sure you know the names of the parties – meaning the different people, companies or organizations involved – in the case. This may require some quick research. For instance, a search for “abortion pill case” results in this article. When I skim the article, I learn that the Food and Drug Administration is being sued by the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, so these are the parties in the case.

Once you know the names of the parties, there are several free options available to find the court’s actual ruling, which is called a written opinion. You can search on the Supreme Court’s website or on Oyez.org. On both sites, the default search option is for cases in the current term, which is October 2023 through October 2024. Take care to adjust your search for the correct time period if you are looking for a case decided in a prior term.

Because the opinions are often long, I recommend getting a PDF version of the case so you can more easily skim and find what you are looking for.

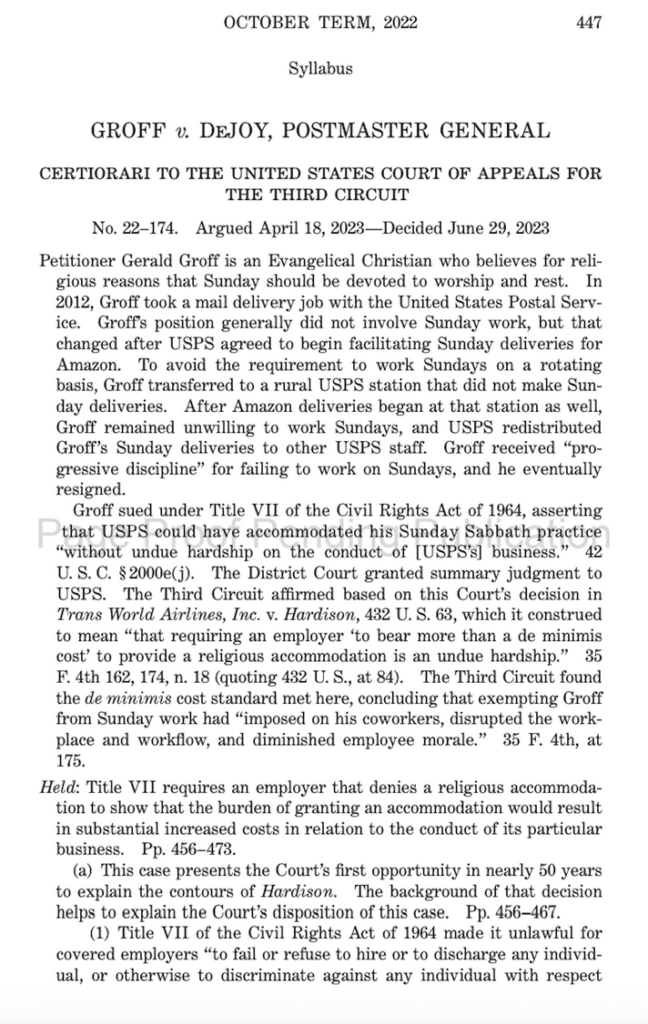

Is this entire document the opinion of the case?

No. Once you get the PDF of a specific case, the document begins with the “Syllabus,” which is the court’s summary of what the case is about. It briefly sets out the facts and the legal principles, as well as the outcome of the case. This is like the blurb on a book jacket — a preview or summary, but not the entire work.

Keep reading to find the part labeled “Opinion of the Court,” which represents the court’s official decision in this case. The opinion will include an opening sentence along the lines of “Justice X delivered the opinion of the court.”

Toward the end of the opinion, you may see what is called a “concurrence” and/or a “dissent.” A concurrence generally means that the justice who wrote it agrees with the decision of the court – what is called the “holding” – but does not agree with the reasoning for getting there.

A dissent, on the other hand, disagrees with the decision of the court for any number of reasons. The top of the page will be labeled either “concurrence” or “dissent” and will also state which justice or justices authored it. There may be more than one concurrence or dissent in an opinion.

While a concurrence and dissent are important records of some justices’ thinking on the issue, they are not part of the opinion. The content of a Supreme Court opinion is considered “binding precedent,” which means all other courts must follow this decision in the opinion. The concurrence and dissent are not binding, meaning no court is obligated to follow those decisions. However, they are both valuable records and can provide guidance for future legal cases about how justices are likely to view certain legal arguments.

How do I make sense of the opinion?

The opinion is generally made up of four parts: the facts, the issue, the holding and the reasoning. These parts may not be specifically identified with headers, but they are the main ingredients of the opinion. Here’s what each part means.

Facts: This is a summary of who is suing whom about what and why. It may also describe which lower court or courts decided the issue and how it was decided before the case arrived at the Supreme Court. You’ll find the facts at the beginning of the opinion.

Issue: This is the question the court is being asked to decide. It might be located at the start of the opinion or at the end of the facts. Sometimes, there may be more than one issue. To find the issue(s), look for key phrases like: The question before us is …

We are asked to decide if …

We consider the question whether …

Holding: This is the court’s answer to the question(s) posed. This answer will serve as precedent to guide future cases on this topic at both the Supreme Court as well as lower courts. Sometimes the holding can be found right after the issue. Other times, it appears much later in the opinion or at the end. Some key phrases identifying the holding:

Therefore we conclude …

We hold …

We find …

Reasoning: Most of the opinion will be the reasoning. The reasoning explains how the court reached its holding. The court may explain which existing precedent – holdings from prior Supreme Court cases – applies. The court may also spend time explaining how to interpret language in a federal statute or balance conflicting rights, such as one person’s right to privacy and another person’s right to free speech.

Other tips

Opinions are often long, so skim first. Consider reading simply for organization, like finding the headings in a textbook chapter to understand the broad ideas. Where does each part begin and end? How many concurrences or dissents are there, and who wrote them?

The concurrence or dissent may not describe the issue the same way as in the opinion. This is precisely why a justice writes a separate explanation – they may feel that the court should have framed the issue differently and perhaps reached a different outcome.

Finally, do not expect to fully understand the content of the opinion at first glance. Even experienced legal professionals need time to carefully read the opinion. Instead, aim to get a feel for the organization and nuance of the opinion. These techniques will give you some footing to begin to make sense of the case and find the parts that are of interest to you.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.