Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Rhode Island Weather for June 18, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 18, 2025

- Johnson & Wales University names Joseph Greene, Providence campus president, to lead major new initiatives June 18, 2025

- To Do in RI: Hospitality employees and Newport Co. residents welcome at free Newport attractions June 18, 2025

- Time for Sour Grapes – June 18, 2025 – with Tim Jones June 18, 2025

- It is what it is: Commentary, 6.18.25 – with Jen Brien June 18, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Downtown Providence 1970 – David Brussat

by David Brussat, Architecture Here and There

Photo: proposed Westminster Mall is from Downtown Providence 1970. (Author’s archives)

This is the second half of Chapter 15 from Lost Providence. Chapters leading up to “Downtown Providence 1970 Plan” in Part II of the book are: “Cove Basin and the Railroads,” “The World’s Widest Bridge” and “New Courthouse and Old Brick Row.” The subsequent chapters, from which I will select for reprinting, are: “The College Hill Study,” “The Interface Plan,” “Capital Center Plan,” “We Hate That,” “The Capital Center Build-out,” “Waterplace and WaterFire” and “The Downcity Plan.” The book can be purchased by clicking on the link above.

***

Chapter 15 (second half)

Downtown Providence 1970 Plan

Even from the vantage point of more than half a century, it seems the height of arrogance to have argued back then [in 1960] that the 1970 plan was about “the beautification of urban ugliness.” After two decades that forced every U.S. city to defer maintenance pending the outcome of economic depression and world war, why did this plan call for the demolition of City Hall, Union Station and other old buildings and their replacement with dozens of new ones radically different in appearance, along with the renovation of many old building façades in this same contrasting aesthetic?

Would not the cleaning, maintenance, repair, renovation and restoration of old buildings have served the city better – and obviously so? Would that not have represented a more achievable, bit-by-bit approach capable of fitting within fiscal constraints that had challenged the city for decades – obviously so now, to be sure, but just as obviously so even then?

One part of the 1970 plan was the proposal to “improve” the city’s “ground floor.” The idea, not a new one, was that better landscaping, lighting and street furniture could work wonders. But in practice this ground-floor plan amounted to covering up the ornamental first- and second-floor façades of downtown commercial buildings with faux modernist siding, especially on Westminster, and installing light fixtures, benches and other street furnishings radically different in style. The plan’s authors describe the concept as part of the plan’s proposal to pedestrianize the city’s main shopping street (“Westminster Mall”):

Many of the stores fronting on the Mall are old-fashioned and the façades above them are blighted and dirty. … The store fronts have been given a handsome, unified treatment and the irregular and competitive “stickout” signs have been replaced by a row of dignified “flat” signs.

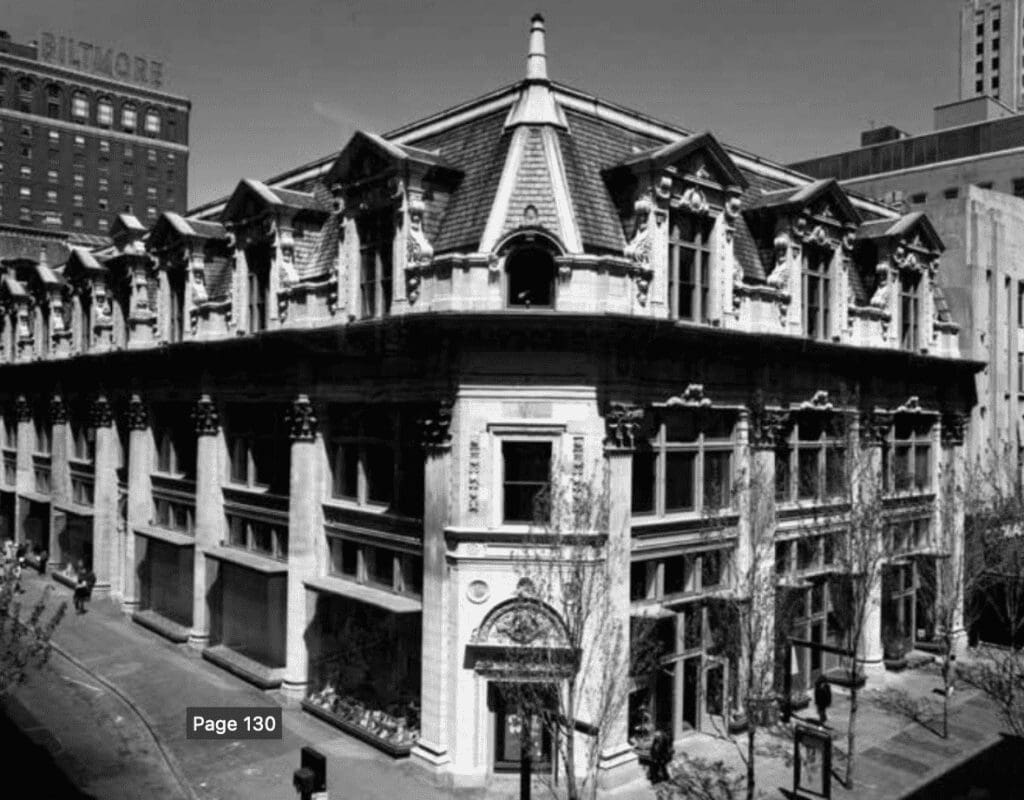

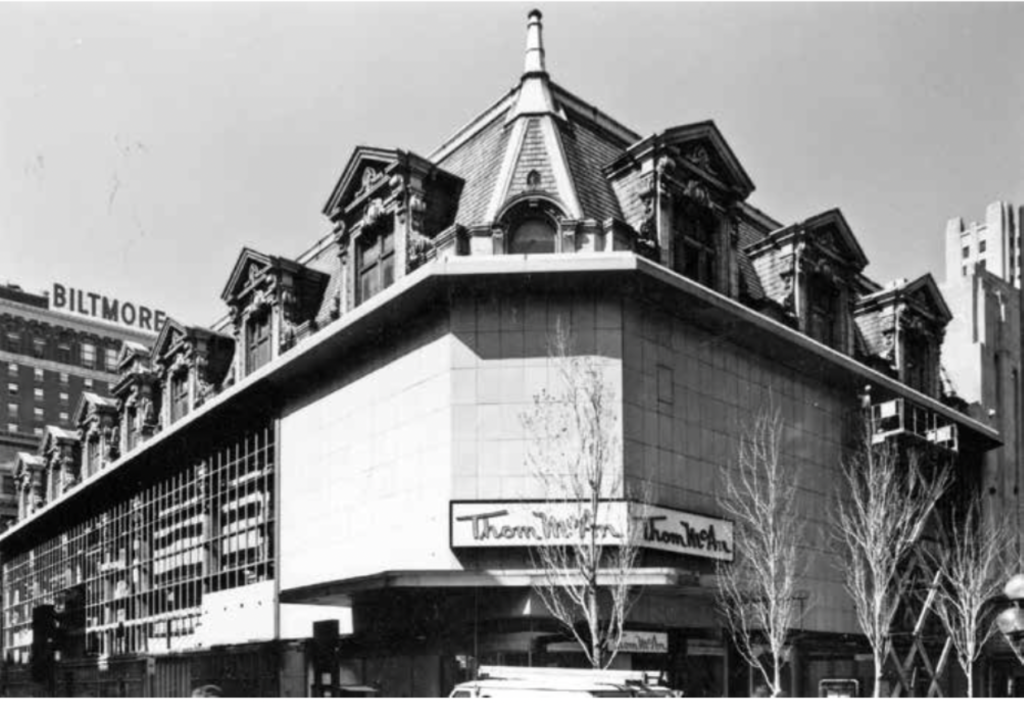

And some of that faux siding was already applied before the 1970 plan. The chief example of this was the Old Journal Building, completed in 1906, and described in the RIHPHC’s 1981 downtown survey: “Originally one of the most elaborate Beaux-Arts buildings in downtown Providence, the Journal building was most unsympathetically altered in a clumsy attempt at modernity.”

The ornamental capitals of its colossal engaged Corinthian columns were sawed flat to make way for aluminum sheathing of pale green below the building’s cornice, covering the first two stories and housing a Newberry’s five-and-dime store. Above the cornice, thirteen dormers encrusted with swags, scrollwork, florid brackets and other detail remained visible, peering down forlornly from the third story at its ugly new skirt. That this desecration was performed in the 1950s, before the 1970 plan was announced, suggests that the attitudes that led to the plan already infested the city’s planning apparat.

In 1983, the sheathing was removed and the original façades were meticulously restored by the Estes Burgin Partnership. Interestingly, the language of the entry quoted above from the RIHPHC’s 1981 survey was dropped from the 1986 Citywide Survey of Historic Resources. The “clumsy attempt at modernity” became “This change, much admired at the time, was consonant with the modernization goals espoused by the city planning department.”

Clearly, however, by the 1980s, the plan first announced in 1960 was in bad odor. Westminster Mall had been partially completed, and so had the Weybosset Hill Project. It sequestered the Roman Catholic Cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul behind modernist low-rise apartment blocks for the elderly, creating a plaza that few people actually visit, today or back then. Three huge residential tower blocks known as The Regency required eradicating the entire fabric of buildings at the western end of the “bow” where Westminster rejoins Weybosset. No other major downtown portion of the 1970 plan was ever attempted, although some assert that the clunky Civic Center is attributable to the 1970 plan.

There was a lot of self-congratulation when the 1970 plan was announced, but then silence – decades of silence. Mayor Joseph Doorley, who succeeded Walter Reynolds in 1965, loved federal urban renewal and the Model Cities program – that is, he loved buckets of federal money – but he failed to push for a revitalized Providence with the sort of vigor unleashed two decades later by his successor, Mayor Vincent A. “Buddy” Cianci Jr., when his turn came around.

In Providence: The Renaissance City, Francis Leazes and Mark Motte put their finger on a salient truth:

The failure of the Downtown Providence 1970 plan to generate interest contains an important early lesson concerning renaissance activities: sometimes the decision not to do something is more important than actions undertaken. … It was a fortunate inattention to downtown renewal planning and the eventual demise of federal urban renewal that would mark the 1960s as a critical epoch in the future of renaissance Providence. Downtown Providence remained intact.

But maybe even the movers and shakers in Providence really thought the 1970 plan was wrong, or that the public believed it was wrong or a waste of money. Mayors do not normally hold a press conference to announce the failure of a redevelopment project or to answer questions why it failed. It just peters out.

In the 1950s, before the 1970 plan was announced, the railroad tracks between the State House and downtown had largely completed their conversion to parking lots. A parking slab jutting out into Burnside Park from Union Station replaced its front canopy, which was dismantled. The station was painted gray. Buildings were being demolished to create parking lots. The wharves that still slanted out into the river now hosted parking, not rail spurs. A few modernist buildings had arisen, but property owners lacking the ambition to raze and roll the dice on a newfangled replacement instead slicked over their ground-floor façades. It is possible the “visual identity” created by this “hodgepodgization” of downtown in the 1950s paved the way for the aesthetic incongruities of the 1970 plan.

In addition to its ban on all curbside parking, the 1970 plan proposed building up to eleven new parking garages downtown. One, considered of the highest planning priority, would have required demolishing several of downtown’s most cherished commercial buildings – the Equitable Building, the Wilcox Building and the Bank of North America building – along that astonishingly beautiful stretch of Weybosset as it curves to meet Westminster near the river.

So on top of all this, on top of its eager assault on much of the city’s loveliest architectural heritage, the 1970 plan might have seemed to some civic leaders like piling on. One thing’s for sure: it did not take off. It may be supposed that Mayor Reynold’s successor, Mayor Doorley, in the back of his mind, even as obstacles and opponents emerged to complicate the 1970 plan, was feeling that enough was enough. The least of his worries might have been the refusal of the railroads – there they go again! – to cooperate with the idea at the heart of the plan: the relocation of the railroad tracks that formed the so-called Chinese wall.

***

The next segment of Lost Providence will be the first half of Chapter 16, “The College Hill Study,” which purportedly saved Benefit Street.

___

To read other articles by David Brussat: https://rinewstoday.com/david-brussat-contributing-writer/

My freelance writing and editing on architecture and others addresses issues of design and culture locally and globally. I am a member of the board of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which bestowed an Arthur Ross Award on me in 2002. I work from Providence, R.I., where I live with my wife Victoria, my son Billy and our cat, Gato. If you would like to employ my writing and editing to improve your work, please email me at my consultancy, dbrussat@gmail.com, or call (401) 351-0451