Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Real Estate in RI: Seaside waterfront communities are all the rage. Who’s buying – Emilio DiSpirito June 6, 2025

- Outdoors in RI: 2A votes, Charter Yachts, active summer programs, garden tours, aquatic weeds… June 6, 2025

- All About Home Care, with two Rhode Island locations, closing after 22 years in business June 6, 2025

- GriefSPEAK: Angel wings with footprints – Mari Nardolillo Dias June 6, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 6, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 6, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Creative Capital capitulation

by David Brussat, Architecture Here and There

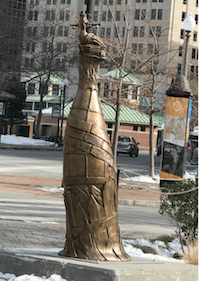

Photo: One of two bus shelters newly installed in Providence’s innovation district. (William Morgan)

In recent decades, art in Providence has served as a wrecking ball aimed not just at beauty but at the very concept of art, in a city that depends on art for its historical character, even as it brands itself the “Creative Capital.”

Two news items: First, the R.I. Department of Transportation recently installed a pair of bus shelters in Providence’s “innovation district” that frankly look more like instruments of torture than items of street furniture. They are not really bus shelters; they are works of art. The last thing their designers want is for people to think they are a pair of measly bus shelters. The second news item is the destruction by fire, widely believed to be arson, of a large public sculpture called “Like a buoy, like a barrel” that looks like a gigantic multi-colored hand grenade. Like the bus shelters, this actual sculpture is also in the innovation district, on Dyer Street at the recently completed Wexford Innovation Center.

It pains me to reveal how very minor is my disappointment at the fate of the buoy/barrel sculpture by artist Steven Siegel for The Avenue Concept, which supports the installation of sculptures and murals in the city. I cringe at the wanton destruction of any art, even bad art. It is an assault on my freedom as much as on theirs. Artists and their corporate sponsors are free to express themselves through art, and I am just as free to dislike and disagree with their work, yet am not free to exact vigilante justice against its existence on my own. I deplore what happened to “Like a buoy, like a barrel.”

I hasten to add that nothing on the website of The Avenue Concept suggests that it or Steven Siegel are in sympathy with the recent unpleasantness involving riots and the destruction of sculptures across America. But the art supported by the agency (and just about everyone else in the art world) has a very long pedigree, one which has seen art decline over a period of a century or more from works by artists of vast talent inspired by greatness, to what we have today – works done by people with little or no artistic talent, many of which appear to have been conceived and executed by kindergarteners, requiring little more than the chutzpah to bamboozle society into thinking that their tinkering constitutes art.

Perhaps this decline reflects the inevitable trajectory of democracy, but it can and should be resisted. It is being resisted today, feebly, in that a few excellent sculptors and other artists continue to create in the old way, with the support of an ever diminishing number of patrons and institutions dedicated to their works and livelihoods. No cities seem the least bit interested in commissioning sculpture by such artists.

I personally have resisted for years, writing, for example, to name just two Journal columns that pop to mind, about bad art commissioned for the Rhode Island Convention Center, such as “Cavorting Inanity” (my title) on the facility’s garage, and the ugly temporary sculptures installed on downtown’s Parcel 12 before a hotel was built. Nevertheless, I praised sculptor Gillian Christy’s leaves twining up a West Side mill chimney and her pleasing “watch tower” on Kennedy Plaza, to suggest that talented sculpture emerges even amid the ilk of today’s aesthetic miasma. After a stay of a year or so, for example, the not regrettable (albeit not comprehensible) sculpture at left recently disappeared from near the Biltmore Hotel on Kennedy Plaza. Many of these new-age works seem meant for merely temporary placement – perhaps a hint of self-awareness?

Again, the decline of sculpture, not to mention statuary, may have been inevitable in a democracy. But opening the doors of art to vastly more individuals did not need to require inviting such a steep degradation of artistry to inhabit its halls. It’s hard to imagine art becoming much more debased than it is. Eventually, everyone who wants to be an artist will find no obstacle to being one. Lost in the process will be the honor and distinction society has long placed on the heads of artists. Some of this is already gone. How can the historic role of the artist in shaping our culture survive this comedown? How long can the culture survive?

We are starting to see some answers to these questions in the news. The work of creative artists enables the designers of bus shelters to suppose that they have a higher calling – bus shelters as art! It’s becoming more difficult to distinguish a bus shelter from a work of art. And it’s becoming more difficult to tell an artist from the computer technician who designs the bus shelter. This is not a Providence phenomenon, far from it; you can see it happening all over the world. It is difficult to tell the president of a charitable foundation from a director of a neighborhood nonviolence cooperative. It is hard to tell a protester, let alone a mostly peaceful protester, from a rioter: an impossible task, apparently, if you are journalist. Plumbers, say, have not yet been bitten by the bug, but it’s only a matter of time before plumbers start to believe that their work, properly conceived, is as creative as a work of art. Then, perhaps, we will all notice that the nation is in trouble.

Art once told the American story so that every citizen could understand it at the most basic level. Nowadays, professors of art don’t understand great art and nobody understands art as it is practiced today. As in architecture, when a building evades comprehension, the public gives it a wacky nickname, say, a common kitchen utensil, such as the Cheesegrater in London. Similarly, I would not be surprised if the torched sculpture in Providence goes down in history as the “hand grenade” or if the public starts calling the city’s new bus shelter design “The Rack.”

This all makes dialogue and understanding more difficult at all levels, and throughout society, with mayhem and chaos the intended result. Which is certainly not the vision of The Avenue Concept, at least not intentionally. But there are people out there who are watching and applauding the decline and fall of art and almost everything else. As the city with, arguably, the most artful historical character in the U.S., Providence has the most to lose if this continues. And it is speeding up, not slowing down.

For complete article: Creative capitulation in Prov

My freelance writing and editing on architecture and others addresses issues of design and culture locally and globally. I am a member of the board of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which bestowed an Arthur Ross Award on me in 2002. I work from Providence, R.I., where I live with my wife Victoria, my son Billy and our cat Gato. If you would like to employ my writing and editing to improve your work, please email me at my consultancy, dbrussat@gmail.com, or call (401) 351-0457 https://architecturehereandthere.com/