Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Providence Delivers Summer Fun: Food, Water Play & Activities June 20, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 20, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 20, 2025

- Outdoors in RI: Time to Seastreak – Vets Access – Invasive Alerts – Clays 4 Charity at The Preserve – 2A TODAY June 20, 2025

- GriefSPEAK: Kill Switch – Mari Nardolillo Dias June 20, 2025

- Dr. Rosemary Costigan Named President of Community College of Rhode Island June 19, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

April – a short story by Michael Fine

by Michael Fine

© Michael Fine 2021

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

When Sammy Li stepped back into the West Greenwich house for the first time in ten years, he was amazed at how quickly a house can fall apart.

It was April. The winter had been long, dark and cold, fierce and lonely — but winter was quickly disappearing. Now there were buds on the trees and occasional warm afternoons. Now the daffodils were up but not blooming. The bluebells and crocuses had pushed their way out of the ground, blue, purple and pink on the tan and lime-colored earth, amidst brown leaves left over from the previous autumn. The first insects had just emerged and flitted in the sunlight in mid-afternoon when the sun finally got strong enough to warm the air.

Ten years. So much change in that time. Bobby gone. Diane gone. Jennifer gone. Danny in Seattle and married to a woman ten years older, with four kids the oldest of whom was just six years younger than he was. But working for Google and making a mint. The life Sammy had planned for himself, that he would be retired by now and living with Diane in Florida or in South Carolina in the winter, that they would come home to Rhode Island in the spring to see the tulips bloom and the trees turn green and visit Danny his wife and his kids in Narragansett — that wasn’t even close to how it had all turned out. Just a figment of his imagination. Diane’s imagination, truth be told, because Diane did the thinking and imagining for both of them, and Sammy went to work and came home, as close to six o’clock as he could, every day for seventeen years. Diane’s plans. Sammy’s daily grind. Sammy didn’t plan. He just lived. And was grateful for every day.

But when Diane left him, what, more than fifteen years ago, Sammy’s world collapsed. He had no idea Diane was thinking of other places, dreaming other dreams, wanting more and better, and he certainly had no idea she was seeing other men. They had a nice life. A good life. Everyone knew their place, their job, their role. Yes, Diane made things more complicated by moving them out to West Greenwich, into this old house that needed restoring and away from the restaurant and Sammy’s parents. But it was a good life none the less. There were acres and acres of trees. Sometimes men and women on horseback came cantering up the street. There were spring peepers in the evening at the end of March, and then a chorus, even cacophony of birds that started at five am, just before dawn, hoot owls after dark and coyotes howling and yipping in the distant forest. Sometimes the coyotes howled and hooted all at once, as if in triumph, which made Sammy cringe because he figured that they had brought down a deer.

Sammy liked to watch the birds in their garden in the afternoon. So many colors! Blue jays and cardinals and red breasted robins and those yellow goldfinches, swooping and rising in the air sinusoidally. Sometimes even a Baltimore Oriole and once in a very long while a woodpecker or a bluebird or two, sneaking out of the woods. Even iridescent hummingbirds with red throats, darting in and out of the flowers like taxicabs in New York, as quick and green-blue as the taxicabs were yellow amongst the purple Japanese irises and the yellow bell-shaped foxglove.

The good news was that Diane took care of the house and took care of the gardens, so Sammy didn’t have to do much but be unpaid labor, a strong back or the arms and muscle on Diane’s projects, lifting stones, digging postholes, raking leaves, stripping wallpaper and painting or sanding or hammering where Diane told him to hammer. She was the general contractor. He was the help. When you sit at a desk all day, it is relaxing to work with your arms and back at night and on weekends as long as you don’t have to think.

The bad news, of course, was that the minute Diane finished renovating the house and building the herb garden and the flower garden and putting in the brick walks and the perfect boxwood hedges, she moved on to other, er, projects. She probably began some of those other projects before she finished the house, Sammy thought. How did I miss knowing about all of that? But better not to think about it now. Too little too late. You don’t know what you don’t know. Don’t see what you don’t look at it. Diane left. Bobby died. Jennifer died. Then Diane died, like dominos, one after the next, one sucker punch after the other. Punch drunk, that’s what I’ve been, Sammy thought. Lobotomized. Sleepwalking. Water under the bridge. Doesn’t matter now anyway. You can’t reclaim the past.

The varnish was gone from the oak sill of the front door and the wood had bleached white in the sun and was splintered and cracked. The key didn’t turn in the lock at first. It took a few moments of jiggling the lock back and forth before the key turned at all. Sammy was trying to remember where he’d left the little tube of graphite you can use to free up frozen locks, ten years before, when the key finally turned, and the cylinders clicked open. The door stuck even so. Sammy shoved it with his shoulder, once, twice, three times, with all his weight until it burst open.

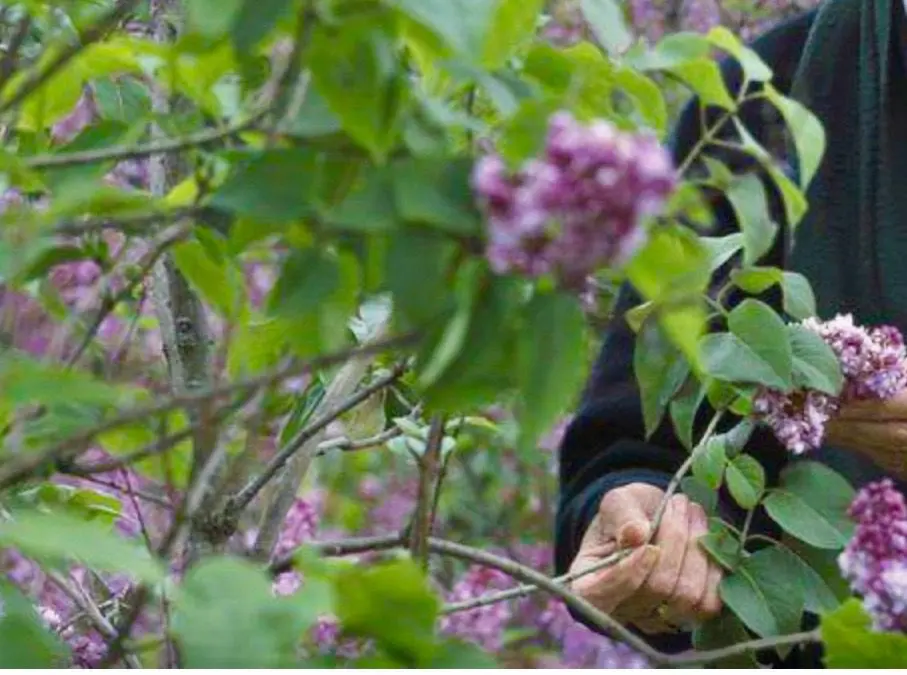

There was dust everywhere, of course, dust and cobwebs, and the front hall smelled like dead mice and squirrel urine. They’d always had problems with squirrels because Diane let the lilacs she loved grow too close to the house and the squirrels used the lilacs as a ladder to climb onto the roof. From there they gnawed their way into the attic where they nested.

The late afternoon sun streamed through the yellow and green stained-glass windows over the door as beams of light that caught the cloud of dust Sammy had stirred up by opening the door and made the air-born dust particles glisten and swirl.

Sammy hadn’t covered the furniture before he left the house. He just left. Just stopped sleeping there the day Diane died. He hadn’t been back once. None of that made any sense, of course. Diane had left home three years before she died. She knew and Sammy knew there was no chance of her ever coming back. Before she died, Sammy believed she’d come home someday anyway. Believed was too strong a word. Hoped, maybe. Prayed for, mostly. Desperately wanted and prayed for, closer to the truth.

But after Diane died Sammy couldn’t face the house anymore, even though she’d cleared out her things years before. Her things. The whole house was hers. Who was she fooling?

Sammy kept paying the mortgage, the oil bill, the electric bill and even the phone bill, but he never went back to the house. Instead, he stayed in Diane’s apartment in Narragansett, which he inherited as next of kin. Slept on the floor at first. On a blanket, on the floor. He never could sleep in Diane’s bed. Had it carted away after a few months, and he just slept on the couch.

.

Next of kin. Strange idea. Married, cheated on, deserted but never divorced, all of which made him next of kin despite the whole sad reality. It didn’t matter. He wanted to live where Diane lived last. He wanted to cook in her kitchen, to use her bathroom, to go into her closets and keep smelling her smell, that strange lavender soap and face-powder smell, but he never wanted to sleep in her bed. It was all stupid. It didn’t fix anything. It wasn’t going to bring her back. But Sammy was living that way the only way he could imagine living. Not that he cared much about life at all now.

Ten years. Huge waste of time. Big waste of money.

The pictures were hanging at odd angles on the wall. Diane’s pictures. Watercolors mostly. Seascapes and pictures of boats in a harbor. Old prints of birds. Diane’s nod to the upper-class, the life she imagined herself, just because her family were Americans, whalers in New Bedford and swamp Yankee farmers at first and truth be told, mostly drunks and womanizers. The men, that is. The women were a quiet, mousy, loyal lot and Sammy was more like them than he was like the men. But some of the women were rebels, jazz singers and actresses and lived large. Like Diane.

.

Funny how pictures move on the walls without you noticing. They get moved by the vibrations from a passing truck, the sonic booms of the fighter pilots who fly training missions in summer, by the claxons from the very occasional freight train on the tracks three miles away, by thunder from the violent storms that blow through in late spring and by tiny earthquakes which shake the house quietly in the middle of the night, a shaking that is so brief and so subtle most people don’t even notice it. By vibrations from the boiler firing in the depth of winter. You straighten the pictures when you pass by. But after ten years of no one living there, of no one to notice and straighten them, all the pictures were now off kilter.

The bannister of the staircase was gray-white and covered with dust, not deep brown and glistening. Black walnut. Sammy could still hear Diane’s shriek when she scraped off the layers of paint and figured it out. Hand carved black walnut, like the baseboards, all likely made from the wood of trees that had grown on their land, back when the house was on two hundred acres, not ten. It took them two years to get the bannister stripped, sanded and refinished, and Diane rubbed that bannister down with furniture oil every week so that it was almost black and as lustrous and warm as an old sepia photograph. It gave the house a grandeur, age and wisdom, as did the single candle chandelier that hung over the stairway. Understated elegance. History and class. It made them look smarter and richer than they were. People would ooh and ahh when they came into the house the first time and saw the entry hall and the living room off to the left and the dining room with its elegant but simple chandelier and the mahogany and maple display cases of old china off the living room.

Not going upstairs, Sammy thought. I’m not ready for that yet.

He walked past the stairs and past the tiny lavatory they’d built under the stairs for company. Past the coat closet and into the kitchen, half expecting to see a flood on the floor from broken pipes. The kitchen was right under the bathroom, Sammy knew, from all the times a toilet upstairs had overflowed, wrecked the ceiling and flooded the kitchen.

There was no flood this time.

But there were dishes on the table and in the sink.

The floor had been swept.

There were cans and cereal boxes on the counter.

For a moment, Sammy wondered if he’d left the kitchen that way when he left the house after Diane died. But Sammy wasn’t like that. He never left dishes piled in the sink, and the counter held brands of cereal that Sammy never ate.

Someone had been in their kitchen. Someone was living in Sammy and Diane’s house.

“Hello?” Sammy said, his voice barely loud enough to be heard in the kitchen. He shoved a chair that had been left in the middle of the floor back under the table and did that briskly so that the chair-legs scraped against the floor and made enough noise to be heard beyond the kitchen itself, a noise of someone present, someone moving about.

Then Sammy listened for footsteps.

And heard nothing.

“Hello,” he said again, louder.

The door to the back stair was open. Someone sleeping upstairs should have heard him.

Sammy stepped closer to the staircase.

“Hello!” Sammy said again.

But he held himself back from going up the stairs. He didn’t know the first thing about the person who might or might not be sleeping above him. Could be a friend or relative down on his luck, who knew Sammy wasn’t using the house and let himself or herself in. Could be just some random homeless person, who had somehow found him or herself out in West Greenwich, broke into the house, found it vacant and just stayed. Could be an ex-con or some escaped prisoner or a drug dealer, someone prone to violence. Could be anybody. Sammy was not so sure now he wanted to go upstairs and find out.

Then he heard a chair scraping against the floor, a man’s yawn and footsteps, a closing door and then the toilet flush.

I’m in over my head, Sammy thought, and he backed up, turned and went out by the kitchen door.

There was a new silver and black BMW parked near the kitchen, pulled in from the driveway so you couldn’t see it from the road. Tinted windows. This guy has taste, Sammy thought. Flashy car. Expensive car. Wise guy. So, what’s a guy who drives a car like this doing in my house?

I’ll give him a minute, Sammy thought, and then I’ll knock on the kitchen door. Wait, maybe that’s not so smart either. He’s living in the back of the house so no one will notice that he’s here. I don’t know a thing about the guy. Maybe I’ll wait and watch him leave. He just woke up. Maybe he’s off to work or something and I can get a picture of him on my cell phone. And then go to the police.

Sammy stepped into the bushes next to the garage. More lilacs. Not very good cover yet. The leaves just starting to bud. He took a picture of the BMW’s license plate with his cell phone. Connecticut plates. What’s that about, Sammy wondered. Snazzy state. Classy car. So where does this guy get off living in my house? How does some dude from Connecticut even know that my house exists? Sammy took a few steps backward, so he was hidden by the corner of the garage. Very weird, hiding from someone living in my own house, just waiting for him to go away. When he goes, I’ll call the police and then get a locksmith out here to slap on a new lock. That should fix it.

Sammy waited ten minutes.

He could see a shadowy form through the windows moving about in the kitchen. The man (he thought it was a man — broad shoulders, brusque unhesitating movement) stalked from place to place, not settling. But not leaving either. Sammy thought he could hear a man’s voice and thought he could hear the man’s voice raised, even shouting. There could be two people in the house, or three, or four. But only one figure, moving behind the windows, in and out of the shadows. Put the lights on, will you, Sammy thought. That way I can get a better look.

The way the figure cocked his head to one side, stayed motionless for a few seconds at a time and then stalked from place to place in the kitchen made Sammy think the guy, if it was a guy, was talking on a cellphone. Something about the shape or posture of the man on a cellphone looked familiar. Something about his size and shape. He was broad but also heavy, a wrestler’s build. But stoop shouldered. He stood like he was afraid of something, ashamed of something, maybe afraid to stand up. Bald, maybe. Sammy imagined a face with a big nose, baggy sad dark eyes, a guy with a five o’clock shadow and a tattoo on one shoulder that went up to his neck.

Wait a second, Sammy told himself. Slow down brother. You’re imagining Tony, one of Diane’s boyfriends. The worst one, the one with the Corvette who wore black open necked shirts, a big gold necklace and sunglasses in the house, who made out like he was a connected guy, the one who spent half his life at Twin Rivers and Mohegan Sun. How had Diane ever let herself get hooked up with a guy like that anyway?

Couldn’t be. That was ten years ago. That asshole had to be in jail or dead by now. Sammy was pretty sure that Tony hit Diane, something Sammy couldn’t imagine. A man hitting a woman. A woman tolerating that. Diane hurt. Diane in pain. And going back for more. She broke an arm and an ankle when she was with him. She claimed she fell down a flight of stairs at his place in Connecticut. Sammy was pretty sure Tony threw her down those stairs. Sammy couldn’t bear the thought of it then. It drove him crazy then. But there was nothing, absolutely nothing he could do. And he couldn’t bear the thought of it now either.

Man was the yard overgrown. Ten years. Trees had sprouted and grown in the flowerbeds and the herb garden and amongst the rhododendrons, azaleas and boxwood. Wild grapevine, Virginia creeper, greenbrier, trumpet vine and wisteria in thick veins twisted into the trees, a chaotic mass of jungle, of life itself that had formed into a wild curtain and was killing the arborvitae, the hemlock and the dogwood. Wrens and robins darted in the bush. A woodpecker hammered nearby. Two doves who’d to one another from the electric line connecting the house to the street.

Ten minutes. Fifteen minutes. Twenty minutes. Wait a second, Sammy told himself. This is my house. What am I hiding from?

Fuck this shit, he said to himself. He walked out of the bushes, opened the storm door and knocked on the glass part of the kitchen door.

The floorboards vibrated. A man’s shadow fell on the door as it was jerked open,

“Whaddaya want?” the guy said. And paused. “Sammy, Sammy boy, how the hell are you?” the guy said.

It was Tony. He grabbed Sammy’s hand, shook it hard and then wrapped Sammy in a bear hug. “Tony. Remember me?”

Sammy evaded the hug pushed past Tony into the kitchen.

“You’re one person I’ll never forget,” Sammy said. “Though I would if I could. My life was cursed the day you were born.”

“You don’t mean that. That shit was a long time ago. We had Diane and we lost her. Very sad,” Tony said.

“Sad? You think Diane dying was only sad? Like some song or a movie? You totally fucked up my life, man. You took my wife and my family. I slept on the floor curled up in the fetal position for a year. I spent the last fifteen years, fifteen fucking years in a fog, unable to think, unable to sleep, unable to eat and you just call that sad? Do you have any idea how much damage you did? To Diane, to me, to my son, to my whole family?”

“I’m not getting you brother. Diane got lupus and she died. It sucked. She was good people and pretty foxy. Hot, you know, except at the end when she lost her hair and shit. She liked riding with the top down and she liked rock and roll. But I didn’t have anything to do with any of that other shit. That was your life, not mine. I roll with the punches. Make my own luck. Women is women. A dime a dozen. You had a good one but not one that was even going to stay in one place for very long. She just wasn’t built that way.’

“You’re crazy,” Sammy said. “You destroyed my life once and I let you get away with it. So, shame on me. But what are you doing here, today, living in my house? On my land. Back fucking up my life again?”

“No pain no gain. I ain’t fuckin’ anything up. The house was a fuckin’ mess. I fixed it up a little. Poisoned the squirrels in the attic and put a tarp on the roof when that windstorm blew off those shingles. Painted upstairs. Got your plumbing working again. You froze a couple of pipes last winter. Did you know that? I’ll get around to fixing up the front eventually.”

“Say what? How long have you been living here?”

“Since last fall. I been workin’ the dig in Providence, the 6/10 connector project. Kinda a, kinda an expediter. I keep shit moving. Work with the unions. Work with the contractors. Work with the state. I keep everyone happy. West Greenwich is closer than New Haven. Like more than an hour closer. Convenient. Appreciate the opportunity.”

“How did you know? That the house was empty?” Sammy said. “That I wasn’t going to show up and throw you out on your ass, which is what is about to happen right now?”

“I kind of… I miss Diane, you know that?” Tony said. “She threw me out again and again. I’m kind of a cheating bastard. Never could get enough of a good thing. When she was alive, I’d come sneaking back every couple of months. Mostly she’d tell me to go take a hike. But if I kept at it, if I stayed with the program, eventually she’d break down, and we’d start up again for a while. Until I fucked up. Or until she just got tired of me. Anyway, she died. You know that story. She kicked me out maybe a year before she died. She wouldn’t let me near her when she got sick. She wouldn’t even pick up the phone. I dropped shit at her house, flowers and cakes and shit but she wouldn’t talk to me then. Not anymore. I wrote on her obituary page before funeral, at the undertaker’s website, but I saw that got took down right away, so I figured I wasn’t that welcome, you know, at the funeral.

“But sneaking around was a habit, sneaking around, sneaking back into her life. I missed her. So, I’d drive by her place in Narraganset every couple of days, just for old time’s sake, and I drove by here. I never was in this house when she was alive, but she talked about it enough, so I came to see for myself. Came once. Came three times. Came five times, and no one ever around.

“Your car was always parked in front of the Narraganset condo. But it was never here. So, I put two and two together, and one night, when I got done late in Providence, I pulled in here and slept in the car, just to see. And the rest, like they say, is history.”

“You wrecked my life man” Sammy said. “And now you invade my house.”

“Hey, no hard feelings man, ok?” Tony said. “The past is past.”

“Are you nuts? No hard feelings? Don’t you understand what a mess you made of Diane’s life and my life.”

“You’re not getting that Diane didn’t like me much,” Tony said. “She felt sorry for me, I guess. But she was way too good for me, way out of my league. I had nothing to do with her dumping you. She did that on her own, long before she found me. And she dumped me too, over and over and over again.”

‘You threw her down the fucking stairs!” Sammy said.

“We fought, ok. But she gave as good as she got. Let’s leave it at that.”

There was rattling and thumping over their heads and then on the stairs.

“I can’t hear you,” a woman’s voice said. ‘You talkin’ to me?”

A buxom woman with tousled black hair streaked with grey stumbled into the kitchen, her green eyes unfocused, wearing only a man’s French-blue shirt.

“I can’t believe what you have going on in my house,” Sammy said.

“Sammy, meet Maxine. Maxine, this is Sammy. Our, er, landlord,” Tony said.

“Pleasure to make your acquaintance.” Maxine said to Sammy. “You behind in the rent?” Maxine said to Tony.

“Who is this woman?” Sammy said. “You two married?”

“What, to him?” Maxine said.

“Yeah, but not to each other,” Tony said at the same time. “Like I said, life is complicated.”

“Complicated? Not. He is what he is and nothing more,” Maxine said. “And maybe a whole lot less.”

“Come on,” Tony said.

“Let’s just say we don’t go out in public together,” Maxine said. “How do you two know each other?”

“We, um…,” Tony said but Sammy cut him off.

“He knew my wife. As it were. And this is my house. Which he broke into, to be clear. How do you put up with him?” Sammy said.

“Her too? Which one was she?” Maxine said.

“She, well, you don’t know her. One you don’t know about. She passed about ten years ago,” Tony said.

“So, you were fucking this guy’s wife ten years ago and now you’re squatting in his house? What is it with you people? Doesn’t anyone around here have half a brain in their heads?” Maxine said. “I’m outta here. Tony you are so full of shit, well, don’t get me started. I’m done. Just done. Whatever made me think you were even close to a human being?”

Maxine spun around and pulled herself up the back stairs, one hand on the bannister, huffing and grunting, beams of sunlight streaming through the windows catching the whiteness of her fleshy thighs just under where the blue shirt ended.

“Steep stairs,” Sammy said. “It’s a twitchy old house. Lots of nooks and crannies. Crazy place to live. Diane loved it, though.”

“Yeah. She talked about it all the time,” Tony said.

“She talked to you?” Sammy said. “About this house?”

“Yeah. We talked,” Tony said. “I told her things. She told me things. I know shit about her and her life that you probably don’t even know.”

“Unlikely. But all that was ten years ago and none of it matters now. Would you please just get the hell out of my house. And don’t ever come back,” Sammy said.

“I remember everything she told me,” Tony said. “Every word she said to me. Everything we ever did together, which wasn’t much. Every restaurant and dive bar. Even when she was throwing me out, which was most of the time. Weird, ain’t it?”

“It’s none of my business,” Sammy said. “Not my problem. What’s weird is that you took up with my wife and then ten years later you show up in my house. Makes my head want to explode. Now will you please get your things and your friend and get the hell out. You just aren’t my favorite person in the universe right now. Not now. Not ever. No offense. Please just get your things and go.”

‘I get it,” Tony said. I capeesh. I ain’t going to give you a hard time. And hey, nothing personal, ok? No hard feelings.”

Ten minutes later Maxine came huffing and puffing down the stairs, dressed in a red pantsuit with her hair up and her make-up on, carrying an overnight bag. A little trashy but not unattractive. Way better than a guy like Tony ever deserved. Now that’s a pattern, Sammy thought. I don’t get it.

“I clean up pretty good,” Maxine said. “Sorry for the asshole. He doesn’t understand anything or anybody. He’s just a two-hundred-and-fifty-pound tub of lard. Sorry for your trouble. I don’t think he has any idea that he’s doing anything wrong.”

“Just go,” Sammy said. “Nice to meet you and all that.”

Tony came down the stairs carrying an overstuffed suitcase and wearing sunglasses, a black shirt and jeans and wearing a big gold chain, just like Sammy remembered him, just as Maxine walked out the kitchen door, the storm door banging on its frame behind her as she thudded down the kitchen steps. Tony pulled his keys out of a pocket, jammed at a remote control on his keyring, and his car beeped as the trunk popped open.

“You can keep the food in the fridge and cereal and whatnot,” Tony said.” Sorry about the dishes in the sink.”

“Don’t worry about the goddamn dishes. Now go. Just get out. Please. And don’t ever come back.”

“Hey great to see you again,” Tony said as he reached, and paused at the door. ‘No hard feelings, alright?”

Sammy didn’t even watch Tony go through the door or stumble down the kitchen steps. The storm door banged against its frame a second time. Sammy didn’t watch but he heard the springs of the BMW squeak a little as Tony threw his suitcase in the trunk and slammed the trunk door closed. Sammy heard words between Tony and Maxine. He heard the arrogance and the anger. Then he heard two car doors close, one right after the other. The BMW’s engine started. Its tires crunched on the gravel as it backed up to the garage, and then crunched again as the BMW shot out of the driveway, spitting gravel into the bushes behind it.

How weird was that? Sammy thought. At least he left without a scene. Guy like that, you never know. He’ll probably be back, Sammy thought. He sounds a little obsessed. I better change the locks, get a burglar alarm and maybe think about a restraining order.

He thinks about Diane too. A big dumb guy like that. There’s nothing to him, not really. All bluster. No substance. Kind of afraid of his own shadow when you get down to it. He knows he’s got nothing. Nothing.

But what do I have? Sammy thought. A house that’s falling apart. And nothing else.

Sammy went out the door and down the kitchen steps. The storm door banged on its frame. There was a little folding café table surrounded by three small chairs, the kind that you see in Paris, in the cafes and parks, set on an outside patio that had once been covered by white gravel and was now completely overgrown. Diane loved that little table and the chairs. She and Sammy worked for hours one summer to build that patio, measuring and leveling in the hot sun. Now the little table had rusted and one of the chairs was laying on its side.

Sammy sat on one of the other chairs. I also remember everything, he thought. Everything she did. Everything she said. What she wanted. And even what she couldn’t tell me about, and what I couldn’t say or do. Maybe me and Tony aren’t so different after all.

A bluebird landed on one of the lilac bushes near the garage, and sang, just for a moment. A bluebird! Amazing! It was April.

All of Michael Fine’s stories and books are available on MichaelFineMD.com or by clicking here. Join us!

_____

Michael Fine, MD was the Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015. His career has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. He served as Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections; and founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance.

Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, and rural Scituate, RI. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance.

Dr. Fine is past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians, has served on a number of legislative committees for the RI General Assembly, chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the RIDOH, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.