Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Providence Delivers Summer Fun: Food, Water Play & Activities June 20, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 20, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 20, 2025

- Outdoors in RI: Time to Seastreak – Vets Access – Invasive Alerts – Clays 4 Charity at The Preserve – 2A TODAY June 20, 2025

- GriefSPEAK: Kill Switch – Mari Nardolillo Dias June 20, 2025

- Dr. Rosemary Costigan Named President of Community College of Rhode Island June 19, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

“Anyway” – a short story by Michael Fine

By Michael Fine

© 2020 by Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

He was an old white man and he was hard to like, let alone love, and she was a kid, or that’s how she thought about herself, just a dumb kid most of the time but a wiseass when she wanted to be; half Dominican and half Puerto Rican, who lived with her mother and brother in a triple-decker in Pawtucket; who saw her good-for-nothing father once in a while when he got sober enough to remember that he had a daughter after all. Nineteen. Hot, she tried to tell herself, because she tried to be, like her cousins and her friends, but the truth was that she was just a kid who hadn’t seen much of the world at all and only barely knew what day of the week it was. Mother on disability. Brother sixteen. You do what you got to do to keep body and soul together.

He. Mr. Lewin. An old man who just sat there like a bump on a log. He spent all day listening to records on a record player, if you can believe that. He listened to old music that was slow and fake romantic. Lots of violins. No beat, no rock, no punch – nothing alive. The old man just sat there with his eyes closed. Sometimes he sang along, sang to himself. You had to wonder what he was thinking about, what he was remembering.

And the old man wanted things. You’ll bring me a cup of coffee, he’d say. You’ll bring me a biscuit, he’d say, because he liked these weird old biscuits with chocolate on one side that came from England. You’ll bring me a plate of Oreos, he’d say, the only thing he liked that normal people actually eat. Never, do you mind grabbing a cup of coffee, or, how about some of those amazing cookies, or even, would you be so kind as to carry in Oreos, please, which is how they talk in the old movies Jazmin had seen. No. Just, you’ll bring me this. You’ll bring me that. As if that old man owned the world and Jazmin in it. As if Jazmin was just a part of what he owned, like an arm or a leg on someone else’s body. You don’t ask your arm to reach out to pick up a pen, and you don’t ask your leg to take a step. You think it, and it’s done. Your leg is a part of you, and the thought and the action are indistinguishable, all the intention of a single knower; and the arm or leg have no mind or will of their own. In the old man’s mind, Jazmin, and all the rest of humanity, were his, and had no thoughts, feelings or dreams of their own. He was all that mattered. Nothing else existed. There was no one else.

But he paid her enough to sit there, so it really didn’t matter what he thought. She could study at the dining room table while he sat listening to his old records, which she’d change whenever one finished playing. The dining room table was surrounded by windows which looked out on big trees that stood next to a river. Three floors up. Pretty posh place. The sunlight from that height was dazzling, as Jazmin sat and worked on her computer or tried to read books for her courses she didn’t care anything about. You don’t get sunlight like that in a triple-decker on Japonica Street in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, where everything and everybody is crowded together. Even in winter, when she sat at that table, the sun warmed Jazmin’s skin and the light inflamed her imagination. Sometimes she dozed, warm and satisfied and on top of the world, like a lioness dozing on a hilltop after a heavy meal, warm, the top of the food chain, with no worries at all. Sometimes Jazmin just daydreamed, only half awake.

The old man was a grumpy pants, for real, but his bark was worse than his bite, and all he did was sit in that chair. Sometimes he’d call her to help him stand. His walker was next to the chair, and she’d catch his hand as he slid forward on the chair, and she’d pull as he tried to stand. She was the counterweight that lifted him, like a drawbridge she’d once seen open over a river in the Bronx when she visited there, or the deck of a car-ferry that lifted before the ferry left the dock. He’d stand and then she’d position his walker. Then he’d totter off to the bathroom, and a few minutes later he’d totter back again. Jazmin had no idea what she’d do if he fell. He weighed a hundred, maybe a hundred and ten pounds, and she thought she’d be able to lift him. But then he was so fragile, his skin thin and white, like tissue paper, his bony skull and thin arm bones visible under the skin as if he had no flesh at all. Jazmin thought he might break if you lifted him. Sometimes she thought he might break if you breathed on him too hard.

The money was good, and she could go to school, go out on weekends, and still have money to give her mother at the end of the week. Fifteen bucks an hour under the table, three to eleven, five days a week. Forty full hours. Sometimes they asked her to work a twelve-hour shift on a weekend. Time and a half the whole day. Mr. Lewin didn’t take out for lunch. There was a daughter in Boston and a son in LA. The daughter ran the show and wrote the checks.

Then the radio and Facebook started talking trash about this virus. Corona-virus. COVID-19. Whatever. Her mother thought it was a scam from Trump to scare poor people and immigrants away. Trump said it was a scam from the Democrats so they could impeach him again, or something like that. No one talks straight about anything anymore. It was hard for Jazmin to listen.

But that was all in China, so what did it matter. They had pictures of it on TV and online, pictures of purple balls with bumps on them, like a dog toy or one of them sex things that is so nasty. Hard to imagine how those little balls could be killing people in China or would ever kill anyone here.

Then they closed the schools. Then they closed her school. Work on-line, they said. Wash your hands a lot. Stand six feet away. It didn’t make no sense. Nobody Jazmin knew was sick. Just more hype, some other way to get money from poor people and immigrants, people who don’t have enough money already. The old and sick, they said. You don’t need to worry if you are young and healthy. At most, it will just be a cold. If it will just be a cold, what were they making so much noise about? You just can’t believe anything you hear from anyone, anymore.

“You’ll bring me biscuits,” Mr. Lewin said. It was a sunny day and late in the afternoon. There were buds that were dark red and dark green forming on the most distant branches of the trees. The spring crocuses had bloomed, and the petals of their purple and yellow flowers lay over on the ground, still bright, and the daffodils were up and just beginning to open.

“Do you have a pick-up stick?” Jazmin said.

“You’ll bring biscuits. Not pretzel sticks,” Mr. Lewin said.

“No, not pretzels. One of those pick-up thingees. A grabber. A contraption that lets you pick up things that are high up.”

“No pick-up sticks. Biscuits.”

“I need a tool that will let me hand you biscuits from far away,” Jazmin said, louder than her usual voice.

“You’ll bring biscuits. I’m not deaf. Biscuits, just biscuits. Not grabbers or pick-up sticks,” Mr. Lewin said.

“Don’t you watch the news? That virus is going around. I don’t want to infect you,” Jazmin said.

“You’re sick?” Mr. Lewin said.

“No, I’m not sick and I’m not getting sick. But they say I should stand six feet away.”

“You should stay home if you’re sick. Stay in bed. Drink fluids. Take Tylenol. Wash your hands every hour,” Mr. Lewin said. “Don’t you watch the news?”

“I’m not sick,” Jazmin said.

“You’ll look in the closet in the bedroom. There is a grabber there,” Mr. Lewin said. “I watch the news on TV. There is a virus going around.”

Jazmin didn’t talk about her mother’s dialysis much. It was no big deal. Three times a week. Her mother went out in the morning and came back in the afternoon all rung out, looking brown-yellow or even a little green and shrunken like dried fruit. Just a fact of life. Kidney failure. Chronic renal failure, they called it. Her mother would end up in the hospital once or twice a year with infections or what not. But then she’d come out again. You wall it off in your mind. Jazmin’s mother and brother were all she had. You live from day to day, and do what you have to do to exist, to go forward, and to protect each other. That isn’t what you think about. That’s just what you do.

Jazmin didn’t talk about living three people in a two-bedroom first floor of a triple-decker in Pawtucket, either. You do what you got to do. Jazmin and her mother each had a bedroom now. Once Jazmin and her brother shared a bedroom. Now her brother slept on the couch. Crowded? Maybe a little. But it was their life and at least Jazmin’s mother didn’t have to climb any stairs.

First Jazmin’s mother lost her sense of smell and taste. Then her nose started to run. She started to shake with chills. Then she started to cough. You don’t need to be a doctor or a rocket scientist to see what it was. That virus was here now, present in Jazmin’s family. It wasn’t going to leave anyone out, not anyone.

Which meant Jazmin’s mother was going back to the hospital. Again.

“I’m not coming in,” Jazmin said on the phone.

“You’re running late? How late? Speak slowly and clearly. I have a hearing impairment. You have to speak slooowly and CLEARLY when a person has a hearing impairment. Everyone knows that,” Mr. Lewin said. He sounded much more alive than he did in person, as if his brain might actually still be present, someplace back in that wrinkled old head, buried beneath those beady little eyes.

“I CAN’T COME TO WORK TODAY,” Jazmin said, speaking slowly and clearly.

“Don’t shout,” Mr. Lewin said. “I can hear you perfectly well now. You’re sick?”

“I’m not sick. My mother’s sick. She’s in the hospital. I think she’s got the virus and I don’t want to spread it to you.”

“You want to give the virus to your mother? Please speak slooowly and CLEARLY,” Mr. Lewin said.

“MY MOTHER IS SICK. I THINK SHE HAS THE VIRUS. I DON’T WANT TO GIVE IT TO YOU,” Jazmin said

“I see. Don’t shout,” Mr. Lewin said. “You’ll come tomorrow?”

“Not tomorrow. I can’t come for two weeks. If my mother is sick I have to stay home to see if I get sick,” Jazmin said.

“You’ll shop for me?” Mr. Lewin said. It was a strange request. Jazmin had never shopped for Mr. Lewin before.

“I can’t shop for you. They said I’m supposed to stay home for two weeks.”

“You’ll call me tomorrow?” Mr. Lewin said.

“I’ll call tomorrow. If you want,” Jazmin said.

“You’re home alone?” Mr. Lewin said.

“I have a brother. He’s sixteen.”

“Your brother is sick?” Mr. Lewin said.

“No, my brother is fine.”

“Are you sick?”

“I’m fine. Just a precaution,” Jazmin said.

“You’ll call tomorrow?” Mr. Lewin said.

“I’ll call tomorrow.”

“What time?”

“I’ll call at 10:30.”

“You’ll call at 9. I watch a program at 1030.”

“Okay Mr. Lewin. Anything you say. I’ll call at 9.”

First they put Jazmin’s mother on oxygen. But they wouldn’t let Jazmin or Jaime into the hospital to visit.

Jazmin and her mother FaceTimed. It drove Jazmin crazy. Not that Jazmin would have done much or said much if she had been able to visit.

They were used to the hospital. She’d just sit. Get her mother a glass of ginger-ale. Get her mother toast or graham crackers from the little kitchen down the hall, the one for families. She ate some of those graham crackers dipped in milk herself, though the graham crackers often fell apart before Jazmin could eat them. Half a graham cracker would end up at the bottom of the milk carton, and would slip into her mouth, soggy and soft but surprisingly sweet, to drink instead of to eat. Jazmin’s friends and her mother’s friends and her brother’s friends would come by the hospital. They’d have a little party in her mother’s hospital room every night, and it was almost a good time. Except it wasn’t. Mommie isn’t going to live forever. That was the thought that Jazmin didn’t ever think. Each time could be that time. She’s bouncing back, this time, Jazmin thought. But she might not always.

Now Jazmin couldn’t be there at all. She couldn’t smell that funny hospital smell, of some chemical, some disinfectant that they tried to cover up with a fake sweet minty scent, a scent that made Jazmin’s nose run. They made her mother wear a mask, in the hospital, so Jazmin couldn’t see her mother’s mouth when they FaceTimed. She couldn’t see when the corners of her mother’s mouth tilted up and twisted a little when her mother tried to suppress a smile, which was what her mother did when she was about to say something a little mean but a little true, or tease Jazmin, which was what her mother did when her mother was happy and relaxed.

FaceTime was still better than nothing. She’d see her mother’s eyes and they’d talk until her mother got short of breath. Sometimes Jaime would come over and take Jazmin’s phone or push his face into the frame, so he could be with Mommie too. But he was too young and a boy. Jazmin and Mommie talked. They talked about things, about people, and about what to wear, and who wore what when, not anything Jaime or any brother knew about or talked about.

And it didn’t smell like Mommie over FaceTime. Her mother used a powder and had a sweet hidden smell of her own, like bath soap and talcum powder, like the pollen you smell in the springtime when the trees and flowers are in bloom.

They weren’t huggy people, Jazmin and her mother, but they still touched when they were together, a hand on a hand, an arm around a shoulder. Jazmin missed that, even ached for it now. Sometimes FaceTime got Jazmin’s brain confused. There was half of Mommie’s face in front of her. There was Mommie sitting in a chair, talking and close, and Jazmin’s brain thought Mommie was right next to her, in the room, even when she wasn’t. When Jazmin looked up and saw that Mommie wasn’t there, her brain shook a little and she was suddenly unsure of where she was or what, if anything, was safe and secure.

On dialysis days Jazmin’s mother couldn’t talk at all. They’d FaceTime for a few minutes when her mother was on the machine. But Jazmin would sign off in a hurry, so her mother’s head could fall back on the pillow, so her mother could just sleep, which was all her mother had the strength for.

The phone was on ignore but it buzzed and woke her anyway. A part of Jazmin’s brain never turned off. Was always awake. Was always listening. And always kept the afraid part buried.

“You’re late!” the voice said. “It’s eight thirty. Where are you?” It was a gravely old voice, a man’s voice, lispy and slurred. No accent. English, not Spanish.

“Mr. Lewin?” Jazmin said. Her brain would have snapped on if the call was from the hospital or Mommie. But not now. Not for this. No way.

“You’ll come now,” Mr. Lewin said.

“It’s eight-thirty in the morning,” Jazmin said as she yawned. “It’s not Saturday. I come in the afternoons. But I don’t come anymore, remember. My mother is sick. I said I’d call at nine, not come at eight.”

“You’re not coming?” Mr. Lewin said.

“I told you yesterday. My mother has the virus. I don’t want to bring it to you.”

“Who will be here if you are not coming?” Mr. Lewin said.

“Don’t you have a daughter in Boston?” Jazmin said.

“She argues, my daughter. She says I should do for myself,” Mr. Lewin said.

“I get it. You want somebody there. I wish I could,” Jazmin said.

“You’ll come,” Mr. Lewin said.

“I could Skype or FaceTime.” Jazmin said.

“No. You. Now.” Mr. Lewin said.

“I can’t come, Mr. Lewin. I want to come. But I can’t.”

“I want to talk to your supervisor,” Mr. Lewin said.

“I don’t have a supervisor, Mr. Lewin. You know that. I’m my own boss.”

“Have your supervisor call me right back,” Mr. Lewin said, his voice hard as a rock, mean and cold.

Then the line went dead.

Jazmin called her mother and got no answer.

A few minutes later the phone rang again. A doctor. Her mother was intubated. They were breathing for her. She was on a machine. Stable for the moment. But really sick.

Jazmin told Jaime. They sat together in the kitchen. Jazmin got a Diet Coke. Jaime got a text and he looked down at his phone. He was there and gone, both at the same time. Then he went into the living room, where the computer was, and he went online.

Jazmin sat still for an hour. There was no place to go. No one she could talk to. Her phone buzzed. Texts. She turned it off.

Then the doorbell rang. Weird, Jazmin thought. You can’t ring anyone’s doorbell now. Social distancing.

“I’ll get it,” she yelled. Jaime had headphones on and didn’t hear it anyway. Call of Duty, Jazmin thought, as she walked past the screen. Jaime was into it and didn’t see her at all.

There was a small white man in a dark coat with a fur collar and a black hat standing on the stoop. There was a black Lincoln Town Car with tinted windows at the curb in front of the house, its engine running, a steady stream of thin grey smoke flowing from its exhaust. The grass in front of the house had turned green since Jazmin had been outside last. There were little yellow flowers on the spindly branches of the bushes that surrounded the cement porch in front of the house.

Jazmin had mailed the rent. Her mother had it all set up. She had written rent checks a year ahead. Whenever she was in the hospital, Jazmin mailed the rent on the twenty-fifth of the month so it would be there by the first. She had mailed the check a few days before.

Jazmin wasn’t wearing a mask. She put her hand over her mouth.

The landlord was an old Chinese guy, not an old white guy. The man in the hat wasn’t wearing a mask either.

“You’ll come,” the man said.

The man in the hat was Mr. Lewin.

“I don’t want to get you sick Mr. Lewin,” Jazmin said. “It’s only been five days. My mother has the virus, remember? I could have the virus too.”

“You’ll come anyway,” Mr. Lewin said.

“Mr. Lewin. I have a brother who is sixteen. He’s too young to be left alone. He could have the virus too. The virus won’t hurt us. But it could make you really sick. You know that?”

“I have a car and a driver. No one lives forever. You’ll tell your mother.”

“I can’t tell my mother,” Jazmin said.

Suddenly Jazmin’s throat closed, and she couldn’t see. She was short of breath and weeping. Her knees buckled and she fell forward. Somehow Mr. Lewin caught her. They swayed. Then Jazmin found her footing. They didn’t fall.

“I could have knocked you over,” Jazmin said.

“You could have come when I said come,” Mr. Lewin said.

“I could make you sick, Mr. Lewin,” Jazmin said.

“I have to die of something,” Mr. Lewin said. “I just don’t want to die alone.”

“I guess we hold each other up,” Jazmin said.

And then her cell phone rang. She had a siren ring tone. It was really cool. You could hear it whenever it rang. It didn’t matter where you were in the house.

Mr. Lewin got sick five days later, just after Mommie’s funeral. They held Mommie’s body for three days to let the virus burn itself out. They don’t let you have a real funeral now. Only five people. Mommie was being cremated anyway. So, they had a Zoom service in Mommie’s church and something like 300 people logged on. Jazmin sat in the living room next to Jaime. They each sat at their own screens so they both could see everyone. Jazmin kept the video on even though she was weeping. One part of her didn’t want anyone to see. One part didn’t care.

He is one tough old man, that Mr. Lewin. He got a fever and coughed and coughed and coughed. Jazmin went to his house every day to sit with him. Sometimes Jaime came, because Jazmin didn’t want him to be alone. But Jaime just sat on his laptop, still dazed. Crossfire. League of Legends. Fortnite.

Jazmin tried and failed to study.

When Mr. Lewin stopped asking for Oreos and his English biscuits, Jazmin called 911. The EMTs came in all decked out in yellow space suits, face visors and masks, like they were attempting a moon landing. But Mr. Lewin told them to go away.

Mr. Lewin got better. It took a week, but he started to eat again. The fever disappeared. Then the cough faded, and after another week he was back to himself, back to “You’ll bring me” and “Speak slooooowly and CLEARLY”.

The world isn’t even close to fair.

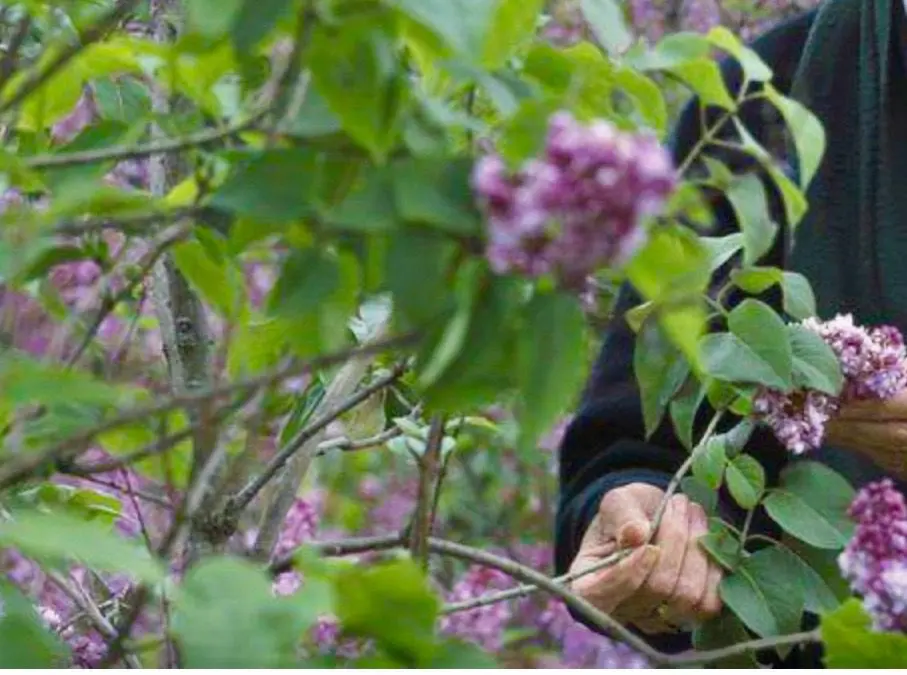

Now the lilacs are blooming. Anyway.

All of Michael Fine’s stories and books are available on MichaelFineMD.com or by clicking here. Join us!

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor to Mayor James Diossa of Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.

He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.

He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.

Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.