Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Senior Agenda Coalition of RI pushes wealth tax to fund programs for older residents – Herb Weiss June 2, 2025

- How will Artificial Intelligence (AI) impact the future of work – Mary T. O’Sullivan June 2, 2025

- Real Estate in RI: Tiverton contemporary for $1.27M June 2, 2025

- Our Networking Pick of the Week: Coffee Hour at Provence Sur Mer, Newport June 2, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 2, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 2, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

The Interface Plan (cont), Lost Providence – David Brussat

The second half of Chapter 17, “The Interface Plan,” opens with a continuation of comments on architectural trends in the early 1970s and then describes the Interface: Providence plan at some length, including several illustrations not included in Lost Providence. The “turmoil” referred to in the opening sentence below refers to the accurate critique of modernism by postmodern theorists, who nevertheless refused to follow up their critique with anything beyond a sort of cartoonish classical decoration of modernist boxes.

***

Amid the turmoil, which lasted for about a decade and amounted to nothing, the postmodernists’ assault on modern architecture did create a small opening for architects interested in reviving the traditional building practices that had been declared null and void by the modernists.

The history and technique of classical architecture and its traditional brethren had been expunged from the curricula of every school of architecture in America, but even as late as 1970, the growing accumulation of built modernism was surrounded by reminders of what might have been. Organizations arose to oppose modern architecture, such as Classical America, cofounded in 1968 by Central Park curator Henry Hope Reed, author of The Golden City. His book paired photographs of comparable modernist and traditional architecture; no words were required (not that he didn’t provide them anyway).

Penn Station in New York was demolished while jaws hung open among the elite in Manhattan. The preservation movement went on high alert. In 1976, the year of America’s bicentennial, the Providence Preservation Society celebrated its twentieth anniversary. But from the National Trust for Historic Preservation on down, they hesitated to challenge the reigning modernist orthodoxy.

Both major plans for the two most celebrated historic districts in Providence, downtown and College Hill, were steeped in modern architecture. Not so with the next major plan to emerge, “Interface: Providence,” published in 1974 after a study led by RISD professor Gerald Howes. Although initiated as a transportation study by way of a class project, it eventually became the first plan to uncover the city’s downtown rivers. Thus did it foreshadow the River Relocation Project of the 1990s.

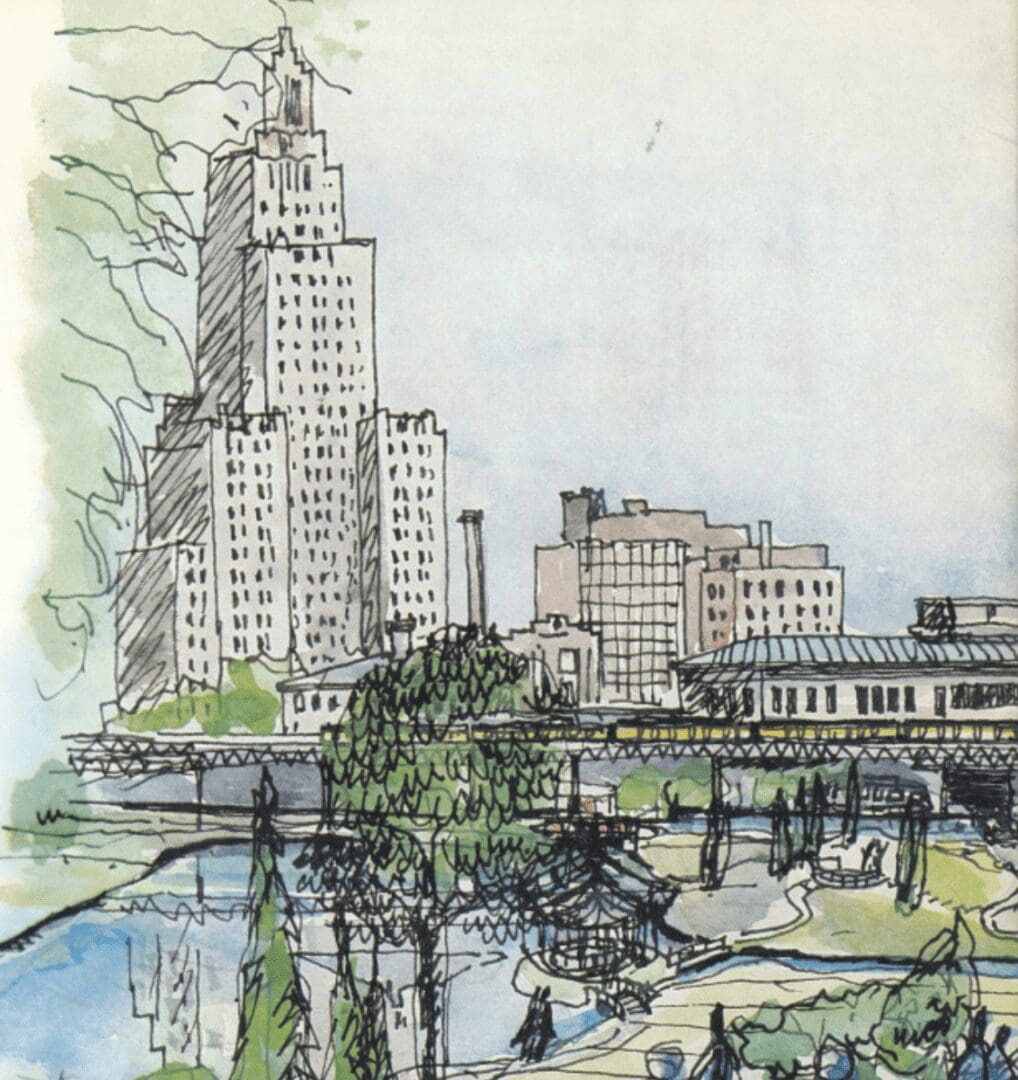

The Interface plan might also be characterized as neutral on the question of architectural style. That was a big step in the proper direction. Yes, it featured, in Kennedy Plaza, a small version on stilts (page 88) of Montreal’s Habitat ’67 – the stacked modular residential development designed by architect Moshe Safdie. But it also proposed a PRT – personal rapid transit – circulating through downtown on tracks raised above the street level by a “colonnade” of clearly traditional design (page 120). The plan’s gently quavering illustrations express a pleasure in the city’s built environment that is incompatible with plans to remove or cover up its longstanding architectural delights.

The plan would not have removed the Chinese Wall. It would, however, have removed automobiles from downtown streets. Its two parking megastructures go unillustrated in the study, for some reason, though each multilevel parking garage was the size of the Financial District. Together they were to provide, at opposite edges of downtown, what curbside spots and sixty acres of existing parking lots provided in 1974. Those lots would have been re-dedicated as infill development opportunities but also as pocket parks in the plan’s extensive proposal for more green space. Above all, the plan would have daylighted the downtown rivers, even adding a large pond (called the “Cove Pond”) on the leafy grounds around the State House.

After commenting on the extraordinary ability the downtown layout affords the average person to orient themselves geographically and to identify primary uses of downtown areas by their appearance, the authors state:

Few cities have this clarity of definition. Also the town has not prospered in the last forty years to a similar extent as other cities, and, while one might think at first sight that this is an unfortunate factor, it has not suffered within its business area from the mad scramble for land with its concomitant high- rise construction.

And while the Interface plan certainly has a “feel” congenial to those who consider the city’s historic architecture to be among its most important advantages, that quote is about the closest it comes to commenting on matters of architectural design. Because we all know about urban renewal and the towering sterility to which the words refer. And Rhode Islanders of that day – more than forty years ago now [in 2017] – had had these connotations pounded into them by a pair of earlier civic plans astonishing in their insensitivity to the city’s architectural heritage.

By 1974, downtown had been built black and blue by the brutal (and occasionally Brutalist) buildings of the period. Beginning with the Fourth Howard Building in 1959, there were in quick succession Dexter Manor (1962), the (Sabin Street) Bonanza Bus Terminal (1963), the Regency (1966), the Blue Cross-Blue Shield (now city planning) Building (1966), the Fogarty Building (1967), Beneficent House (1969), the Textron Building (1969), One Weybosset Hill (1971), the Civic Center (1972), the Hospital Trust Tower (1973) and the Civic Center (1973), with the Garrahy Judicial Complex (1978) and Broadcast House (1979) soon to follow.

Perhaps Interface reflected the dismay that must have been in the air after such a bout, however much people welcomed the attendant jobs and spending. In fact, the Interface plan’s reputation, like that of so much else, comes down to us as a single idea. For the College Hill study, that has been “Saved Benefit Street.” For the downtown Providence 1970 plan, that has been “Never Happened, Thank God.” For Interface, it is “First to Uncover the Rivers.” Reputation does not always align with actual legacy, but in the case of Interface (virtually none of which was implemented) it did. And too bad it was not implemented. Without assessing its practicalities – especially the PRT and the elimination of cars from the central business district – it was an alluring plan.

___

To read other articles by David Brussat: https://rinewstoday.com/david-brussat-contributing-writer/

My freelance writing and editing on architecture and others addresses issues of design and culture locally and globally. I am a member of the board of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which bestowed an Arthur Ross Award on me in 2002. I work from Providence, R.I., where I live with my wife Victoria, my son Billy and our cat, Gato. If you would like to employ my writing and editing to improve your work, please email me at my consultancy, dbrussat@gmail.com, or call (401) 351-0451