Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Vinny Paz to be inducted TODAY into the International Boxing Hall of Fame – CES Boxing June 7, 2025

- In the News… quick recap of the week’s news (6.7.25) June 7, 2025

- Burn with Kearns: Strong without the spend: How scraps became strength tools – Kevin Kearns June 7, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 7, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 7, 2025

- How to advocate for threatened properties: The Heritage Alliance of Pawtucket June 7, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

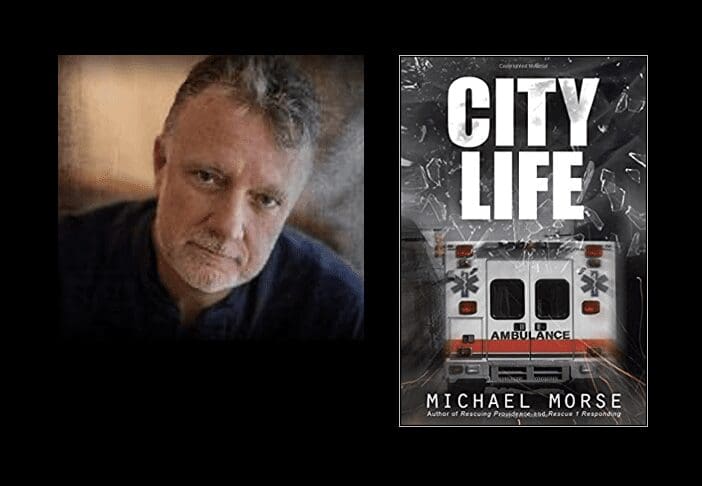

Read with us: CITY LIFE – a book by Michael Morse – Ch. 2

by Michael Morse, contributing writer, excerpts from his book, City Life

Take a breathtaking ride ride along with emergency responders.

Rescue Lieutenant Michael Morse brings you into the homes, minds and hearts of the people who live in one of America’s oldest and most diverse cities. He takes you along for a breathtaking ride as he responds to emergencies that can be heartwarming, hilarious—and sometimes tragic. From the profound to the absurd, from challenging situations to total disbelief, it’s all simply a day at work for our firefighters, EMTs and police officers.

__

Chapter 2

October

Disaster

A car bomb exploded in Kennedy Plaza, killing eight and injuring almost two hundred, eighty critically. I left headquarters at 0844 and headed toward the disaster. En route a suspicious package was found, twenty feet from my planned entrance to the incident. I had to wait.

Walking wounded from a busload of tourists wandered the area looking for help as we staged a safe distance away. Some bled to death where they sat. Soon, the bomb squad cleared the area and we went in, establishing treatment area Bravo. A fifteen-year-old kid walked up to me and grabbed hold and wouldn’t let go. He had a four-foot rod impaled through his shoulder. Dozens of firefighters were on the scene directing and transporting victims toward the four treatment areas. I extricated myself from the kid with the impaled rod and tried to get some supplies and help into my area, but radio communications were impossible.

I sent Renato into the thick of things to round up some backboards, bandages, IV setups, and manpower. While he was gone, ten more patients flooded into my area. I had nothing to give them, no help, no care, no time. I separated them into two groups, red for life-threatening injuries and yellow for those who could wait a few more minutes. The kid with the bar through his body ended up with the yellows. Other people looked worse.

Ten minutes passed. The wounded were restless and starting to panic. Kenny Prew, the officer of Ladder 3, miraculously appeared through the madness with a crew of four. He immediately saw my predicament and got to work. I was able to procure some ambulances from a staging area that the EMS commander had set up, just outside the red zone.

After about a half hour things started to get organized. My patients were reassessed and loaded into the ambulances to be sent to the transportation sector that sent them to the appropriate facility. In ninety minutes, 185 victims were triaged, treated, and transported away from the bombing scene. Seven of the eight dead were infants, their bloody bodies strewn about the area in pieces. A steady rain fell, creating a stream of blood that flowed through the area.

Four hundred people took part in the bomb simulation. It was the biggest drill in the history of Rhode Island. I learned a lot yesterday. I learned that I never want to be involved in a real bombing.

Trivial

He looked dead. Covered in dirt, unmoving, barely breathing. A passerby saw the crumpled heap while driving through the construction site and called 911. A massive highway improvement project is underway in Providence. Our victim collapsed there, a few feet off of Eddy Street, under a bridge. I checked for a pulse, found one, and helped Renato load him onto the stretcher. It was Kevin, a homeless alcoholic I know well.

We put him into the rescue and headed for Rhode Island Hospital, three blocks away. Kevin remained comatose en route, didn’t even flinch while I started an IV. His vital signs were stable but he was completely unresponsive. I turned on the exhaust system in back but it was too late; the smell of stale piss, shit, and vomit had permeated my skin and clothes. I would be reminded of Kevin for hours.

Renato backed into the rescue bay. I got out and swung the rear doors open. As I pulled the stretcher out of the truck my patient sat straight up, looked me in the eye, and said, “WHO WAS THE GUY . . . THAT PLAYED THE CAPTAIN . . . ON SEA HUNT?” I dropped the wheels to the pavement and answered, “Lloyd Bridges!”

Kevin fell back onto the stretcher and we wheeled him in.

Chickens

“I didn’t know that flies could live inside of a refrigerator,” I said to my partner for the night, Ryan. He stood in the center of the room, careful to not rub against any walls. My patient, a fiftyish Cambodian woman, looked in the fridge again, then shut the door. Her family had gathered around her in her tiny upstairs bedroom. Blood streamed down the right side of her face, probably an injury from a fall. The woman opened the refrigerator again; a fly escaped, then she closed it and went over to a window and looked out, ignoring us.

“She’s been drinking again,” said a man, probably her son. I’d be drinking too if I had to live in these conditions. What to me is absolute squalor is to this woman paradise. People from her country have experienced horrors we can only imagine. I have taken this lady to the hospital before. I asked her about her country. She told me.

“I was lucky to make it to the refugee camp,” she said as she recalled her childhood. “I hid in the woods when the soldiers came. I had eleven brothers and sisters. The soldiers killed them all, cut off their heads. They treated my family like chickens in a pen and cut them down. I watched from my hiding place as they killed my parents.”

I think she was referring to the Pol Pot regime. She spent the next ten years of her life living in a tent with tens of thousands of other refugees, scrambling for food and medicine. Eventually she made it out and landed in Providence.

I cleaned the laceration with some peroxide, put a bandage over the wound, and made my way out of the house. I saw that the chickens that used to live in the kitchen cabinets were gone. The doors were back in place, the chicken wire thrown outside.

Day and Night

He sat on a wooden kitchen chair, incoherent, strings of drool and snot swinging from his nose and mouth as he swung his head from side to side. A few empties were at his feet, but I didn’t think that was the problem.

“Is he diabetic?” I asked the people in the room. A woman of about fifty answered yes. The guys from Engine 3 got the stretcher from the rescue and brought it to the door. I wanted to get him into the truck to begin treatment. It wasn’t easy.

“He don’t need that. What you abusing him for?” asked one of the men in the room, agitated. He was a big guy, his distrust for the six middle-aged white guys who had invaded his place in the heart of the projects obvious. He glared at us as the other folks started to squirm. I wish I didn’t notice that they were all black, but I felt the racial tension begin to rise. I have seen situations get out of control and racial divisions become an issue.

“If anybody has any suggestions I’m all ears,” I said as the guys held the patient down and fastened the straps. “If this is a diabetic emergency, we can help him.” The angry man relented, everybody relaxed, and we got the patient to the truck.

His glucose level was 10. I couldn’t believe he wasn’t unconscious. He fought hard, his brain screaming for nourishment. I drew up some glucagon, mixing the sterile water with the dry medication, then injecting it into his triceps muscle. The patient fought harder. Somehow Engine 3 held him still while Renato started an IV. I gave him 25 grams of dextrose through the IV and waited for it to work. He still struggled, but as his glucose level rose he returned to his normal self. The transformation was incredible. He didn’t want to go to the hospital but I insisted. He gave in and we transported him to the emergency room. His friends watched silently from the doorway as we drove away.

Skin Deep

The wounds on his neck and wrist didn’t look bad. I sat him on the bench seat next to the stretcher. The police asked him some questions. “Can you give me a description?” one of the cops asked.

“Three black guys.”

“How much did they take?”

“About eighty dollars.”

“Which way did they go?”

“I don’t know.”

One of the cops started speaking to my patient in Spanish. Indignant, the little Mexican guy on the bench sat up straight and said, “I speak English!” The cops left. On the way to the ER I asked what happened. All the courage Tony had mustered started to crack. His lower lip trembled, tears started to flow. He was ashamed. I didn’t know what to do. Tony regained some of his composure and spoke in a shaky voice, barely under control.

“I was walking up my driveway.” He talked while looking out the rear windows of the speeding rescue. “Fast! It happened so fast,” he said. “One of them held me from behind and choked me. Another had a knife. He put it to my wrist and laughed, then sliced my skin open. Again and again!” I looked at the wounds on his wrist. They didn’t seem superficial anymore. These cuts were deep.

Tony started to weep, covering his eyes with his shirtsleeve. The nice white shirt he wore, freshly pressed earlier in the evening, was ruined.

“Then he put the knife to my throat and wouldn’t let go. They all laughed.”

“‘How does it feel to breathe your last breath?’ one said and pressed the knife harder. I could feel the blood drip down my neck. I thought I was going to die!” Tony lost it completely then, cried uncontrollably until we pulled into the rescue bay. He was mumbling in Spanish now, the bravado he had shown earlier gone. I considered calling the police back, telling them that Tony had been robbed not only of his money, but his pride and dignity as well. If ever there was a hate crime, this was it.

I put Tony on a stretcher and backed out of the way as Rescue 3 rolled past with a level 1 trauma. Two guys were in critical condition after being stabbed in a barroom fight downtown. It occurred to me as I gave the report to Marie, the triage nurse, that this monstrous act would be reported as just another assault and robbery.

The other stabbing victim was rolling in as I was walking out. Tony sat on the stretcher staring into space, unaffected by the chaos surrounding him, but crippled from the turmoil within.

Déjà Vu

Hit and run. It is an epidemic in Providence. People come here from poor countries looking for work. They have no intention of staying here and starting a new life; rather they are here for the money, most of which is sent back home. What little they keep for themselves is used for rent and food and if, there is enough left over, a car. Often, there is no money for insurance or registration, and a driver’s license is impossible. It is easier to drive away and hide, or abandon a cheap vehicle that is on the road illegally, than face the consequences of their irresponsible actions.

John and Regina were minding their business driving on Academy Avenue when another car hit them, forcing them into a utility pole. I arrived on scene, noted the particulars of the accident, immobilized John on a long board with a cervical collar, and put him into the rescue. We moved him onto the bench seat and strapped him in. He said he was okay, but his neck hurt. His wife of fifty-three years, Regina, was next. We put her on the stretcher next to John and transported them to Miriam Hospital at their request.

For us it was an average run, something we do every day. For John and Regina it was a major incident. I found out later that John had broken his neck. He was in a brace for six weeks.

Five months later I was called to a beautiful home on Benefit Street. An elderly person had fallen, the radio said. Sitting on the couch was an eighty-two-year-old female holding her head, small streams of blood dripping between her fingers.

“What happened?” I asked. Her husband walked into the room. I looked at him, then her, then him again.

“She saved my life,” the man said. “I was carrying the laundry down the stairs for her, I tripped and fell over the railing. If she didn’t stop me I would have been killed!” The woman smiled at her husband and said her head hurt.

“It’s not every day a two hundred and twenty pound man falls on you,” she said. I looked at the stairway where the accident happened. I couldn’t believe how lucky these two were. The man fell over a railing onto a landing, then tumbled down eight more steps, landing on his wife. When I got them into the truck, the man on the bench seat on a backboard, the woman on the stretcher next to him, it hit me. “Haven’t we done this before . . .”

Where’s the Remote?

“I am not going anywhere.”

“You took ninety pills.”

“Yeah, but I threw up.”

“But you wanted to kill yourself.”

“That was this morning, I’m okay now.”

“I have to take you to the hospital.”

“I’m not going.”

“I’m not leaving without you.”

“Well make yourself comfortable, there’s a good movie on.”

She was lying in her bed, in her pajamas. Her speech was slow and she looked glazed. Her mother called us when she found out her daughter had overdosed.

“I’m leaving; I don’t want to see what they have to do,” said the mother.

“What do we have to do?” I asked.

“What the last guys did. Tackle her, tie her up, and drag her to the hospital.”

“I’m not tackling anyone,” I said.

“She won’t go willingly,” said the mother.

I pulled up a seat next to the patient.

“Where’s the remote?” I asked the girl. She chuckled, I chuckled, the mother stormed out. After five minutes of “negotiations,” I walked her out to the rescue. She suffered from severe depression. Her medication didn’t seem to be working. She was worried that she was going to miss her radiography class, her “A” average might suffer. I wish I could have spent more time with her; we hit it off pretty well. I told her about my daughters who were around her age.

“You are not alone, everybody has problems,” I said. I think it helped. We walked into Rhode Island Hospital together. She will get a psychological evaluation and may have to spend a few weeks in a psychiatric hospital. They may pump her stomach. I hope not.

Sacrifices

The 1207th is firmly entrenched at Tallil Air Base, Iraq. My brother, Bob, called from there today to catch up on things. The constant hum of generators, rattle and crack of small arms fire and mortar rounds, and the roar of .50-caliber machine guns have replaced the sounds of home—my nieces and nephews playing (fighting), birds in the morning, crickets at night, and the precious quiet moments that we all take for granted.

The sacrifices our men and women in the armed forces are making cannot be understated. I hope that when their friends and families gather around the dinner table, the game, parties, or whatever it is that brings them together, instead of seeing an empty space, they see the person that should be there, and they hold their heads high and realize how fortunate they are to know them. I know I do.

Spanish Lesson

Today, Renato is teaching me how to say, “What’s the matter with you?” in Spanish.

Homeless Alcoholics

To drink and die on the streets of Providence cannot be how so many envisioned their future. What dreams that once filled the heads of the homeless alcoholics who wander the city were replaced by cheap booze and the never-ending need for more years ago. A community of lost souls exists, their plight ignored by respectable citizens who pass them by each day without a second thought. Some panhandle, some steal, some collect government benefits. They all do whatever it takes to survive.

They know each other from chance meetings in homeless shelters, street corners, and emergency rooms. A wary friendship exists as long as the alcohol flows. Once the bottle is empty the quest begins again; friendship forged in desperation becomes secondary to survival. These are lonely lives lived by lost souls, an existence sane people cannot imagine.

Has society failed them, or have they failed society? It is a question I often ask as I transport one after another to the area emergency rooms. Time and time again the ritual is performed. Through the years I have come to know many. Cowboy, after years surviving on the streets, finally found dead in a Dumpster. Sivine, a Vietnamese refuge who dined in the trash cans that line Broad Street, dead in a field. Armand lost his frostbitten fingers one year, his toes another. He liked to sleep under the stars after a night of drinking. They found his body floating next to the pier near the hurricane barrier. Russell, a living corpse, survives on the streets by using Rhode Island Hospital as his personal hotel and the Providence Fire Department his taxi service. Curtis stayed sober for a year or so but has returned, drinking with a vengeance. Debra manages to put on her makeup at the shelter every morning; by afternoon she is drunk again, her tears leaving black trails down her cheeks, urine soaking her clothes. Chris has been missing for a while. I wonder if he is dead, sober, or waiting to make his triumphant return. John has been sober for years now. I see him from time to time. He is pleasant, a little reserved but sober. His drinking career ended the night he drank furniture polish looking for more when the booze ran dry. His friends let him do it and laughed when we took him away, comatose.

There are many, many more. Desperate people do desperate things. There is a lot of desperation lurking beneath the polished surface of the Renaissance City.

Why are these people allowed to roam the streets? Their behavior is habitual, suicidal, and reprehensible. Every day the emergency rooms treat the regulars. Russell alone has cost the hospitals and state and federal government millions of dollars during his drinking career. He takes from society and gives nothing in return. The combined cost caring for these individuals is astonishing. The homeless alcoholics drink until they can drink no more, then either they or a concerned citizen calls 911 for help and a rescue is sent. Nearby true medical emergencies occur, but the victims wait for help while a drunken person is given a ride to the hospital to sleep it off. Day after day, night after night they call.

There is no rehabilitation. There is no cure. There is no easy answer.

Who is responsible for this disgraceful situation? I am a guilty part of the machine allowing this debacle to continue. It is easier for me to put them in the rescue and dump them off at the hospital than to drive away and leave them to suffer the consequences of their actions. I have no intention of risking my livelihood if one of them were injured or died as a result of their self-inflicted condition.

The hospitals are also guilty. Day after day the patients are treated and released. The game is played over and over and has been for years. The Department of Health shares the blame. It is easier to maintain the status quo than develop a plan that will cure them or have them committed. The police department is also complicit. Why aren’t the repeat offenders arrested for being drunk and disorderly or public drinking? Social services such as Crossroads try to help but simply cannot be held responsible for the actions of those who will not help themselves.

The fact that the drinking is funded largely by taxpayer money is another disgrace. Disability payments for alcoholic behavior fuel the very fires that caused the disability. Giving cash to people who have proven again and again that they are incapable of handling the responsibility is insanity.

Who has the courage to end the handouts and put these people where they belong: either prison or committed to a psychiatric facility? So far, nobody. Meanwhile, the bleeding of the health care system continues, and those unable to take care of themselves continue to die, drunk and abandoned.”

I wrote this and submitted it to the Providence Journal. I made sure that six of the papers most popular columnists received a copy. Since then, Debra died; nobody claimed her body. Today, I found out that Russell is comatose at Rhode Island Hospital in critical condition. He had a seizure, fell, and smashed his head on the sidewalk he calls home. More lost souls have taken their place on the streets. I’ve never heard from any of the social commentators at the Journal, their stories apparently not worth the cost of the ink needed to print them.

Code 99

“Engine 11 to fire alarm. Code 99.”

“Rescue 1, received, on scene.”

Renato went to the rear compartment for the backboard. I opened the back doors and rolled the stretcher onto the street.

“Go,” I told Renato. He disappeared through the chain-link gate and into the house. I got the blue bag full of medications and supplies and followed him in, leaving the stretcher thigh-high just outside the gate.

Inside, chaos.

An elderly woman lay on the floor next to a hospital bed, nightgown pushed over her waist. Not breathing, no pulse. A surprised look was frozen on her face. Family members, too numerous to count, ran in and out of the living room screaming. One guy walked into the middle of us, stepped over the dead woman, and went through some dresser drawers, looking for something. He found money, stuffed it into his pockets, and left the room. People kept screaming.

The guys had started CPR and were securing the victim to the backboard. I started to gather information.

“When was the last time anybody talked to her?”

“An hour ago.”

“What medical condition does she have?”

“Arthritis.”

“Where are her medications?”

Somebody handed me a basket full of pill bottles. I took them and headed for the truck. We got the lady inside, continued CPR, and ran the code.

“Renato, I need a line. Seth, you and Ollie keep on the CPR. I’m going to intubate.”

Everybody had a job to do and we got on with it. I found the blue bag that held the ET kit, opened the zipper, grasped the handle and snapped the curved Mac blade in place. The bulb at the end went out. I got my ET kit assembled and tried to tube the patient. The bulb on the Mac blade, my favorite, went out as soon as I snapped it into place. I grabbed a Miller, longer and not as easy to use, for me anyway. I looked at Renato, who was on his third IV attempt. Nothing. I tried to intubate. In between the vocal vocal cords where the tube should entered the trachea never appeared, there was too much tissue and fluid blocking my view. The tube went down the wrong hole. I should never have tried it blind. I took the tube out after deflating the cuff and put an oral airway in her mouth. Seth continued compressions. Renato’s forth IV attempt failed.

“I need a driver. Let’s go,” I said to Miles, the officer of Engine 11.

“I’ll drive, but we’ll have to leave the engine here,” he said. I remembered that they were running with three instead of four. I didn’t think leaving the engine unattended in this neighborhood was a great idea, but I would have left it right in the middle of the street if I thought it may have helped the patient.

“Just give me one of your guys,” I replied. Seth left the back to drive the rescue, Miles drove the engine, Renato continued to attempt IV access, Ollie did compressions, and I handled the airway and bagging. We sped to Rhode Island Hospital. Somehow, I called the ER en route and told them what we had. They were waiting for us when we rolled in. We went directly to Trauma 2 where Megan, the resident, took my report.

“Eighty-year-old female last seen alive an hour ago found unresponsive by family. No CPR until EMS arrival at 2040. No IV access, no tube, asystolic, no blood pressure or pulse.” Megan got to work without missing a beat. I listened while filling my paperwork. I didn’t think the lady had a chance. After half an hour, they had a pulse and her blood pressure was 80/40. Not great, but something.

As we walked out of the ER Megan stopped us and said, “Great job, guys.”

She meant it. Though we did our best, I thought our efforts were a total failure. Apparently, even though most of our efforts were futile, the CPR was enough to give the ER team a chance. I didn’t think the lady would make it much longer, but at least her family would be able to sit with her when she dies.

Problems

Here’s the story: Her daughter is under suicide watch and staying with her grandmother. Her husband, the suicidal daughter’s stepfather, is in court being arraigned on possession of a loaded weapon (9mm). The stepfather is on probation from a previous conviction. The gun was in the truck the stepfather was driving (the mother’s) because the suicidal daughter’s mobster boyfriend gave it to the daughter because her father, a felon wanted in two states for rape charges, has been trying to contact his daughter who he molested. The husband was driving the mother’s truck even though his left leg is useless due to an accident. The daughter had stashed the gun in the mother’s truck. The stepfather was stopped by the police because he was driving erratically, possibly due to his useless left leg, and they found the gun. He was arrested. His wife came to district court to help her husband but was unable to see him. Her left eye started to ooze blood, the marshals called for a rescue, and I stepped in. We walked her out of the courthouse and into the rescue, where she told us her story. Me and Renato let her pour her heart out. She needed somebody to talk to. She said she has a tumor behind her eye that causes bleeding when her stress level rises. I hope she doesn’t bleed to death.

Dignity

I didn’t know how else to ask so I just said it.

“How much does she weigh?”

“Your stretcher won’t break, they did it before,” said her daughter. My stretcher is rated for five hundred pounds. My patient topped that, I’m sure.

“I don’t want to hurt her if the stretcher collapses,” I said. My patient remained motionless on the king-size bed, filling most of the mattress space. She was wheezing with rapid respirations. A crew of ten firefighters had assembled around the bed, a crowd had gathered outside, waiting to see the show. We had to get her to the hospital.

I stacked three hospital sheets, rolled them, and put them next to the patient. Her daughter climbed onto the bed and rolled her mom onto her side. The smell nearly knocked me over when the flesh was exposed, maybe for the first time in weeks. Her head and skeletal system moved to the side, most of her flesh stayed put. I helped stuff the gathered sheets under her until most of her girth was on top. We had to get her through the bedroom door into a hallway, through the outside doorway, down six cement steps, through a crowd, onto the stretcher, and into the rescue. Three firefighters got on each side of her, one at the head and one at the feet.

“On three,” I said and we were moving. Once we got going it was hard to stop. At the bottom of the steps the stretcher waited. People gawked. The stretcher groaned but handled the weight.

“Nothing to see here!” said the daughter angrily to the crowd, who stood their ground as we worked. We got her into the truck and closed the doors. The crowd dispersed, the spectacle over for now. Renato and John stayed in back with me as we made our way to Rhode Island Hospital, steadying the stretcher because we couldn’t lock it into place; it wouldn’t fit. I called the hospital to get a large bed ready.

“I’ve got a sixty-year-old female, approx five hundred pounds, en route. We’ll need a hospital bed, ETA three minutes,” I said over the phone.

My patient turned her head and said, “I’m seventy-one,” her pleasure that I thought she was ten years younger evident on her smiling face.

NEXT: November

___

Miss Chapter 1? Read it here: https://rinewstoday.com/read-with-us-city-life-a-book-by-michael-morse/

___

Michael Morse, mmorsepfd@aol.com, a monthly contributor is a retired Captain with the Providence Fire Department

Michael Morse spent 23 years as a firefighter/EMT with the Providence Fire Department before retiring in 2013 as Captain, Rescue Co. 5. He is an author of several books, most offering fellow firefighter/EMTs and the general population alike a poignant glimpse into one person’s journey through life, work and hope for the future. He is a Warwick resident.

if i had my way would be open reading by local actors in a theater setting,like say trinity rep or at chafee pell on empire street

Excellent and creative idea!