Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Real Estate in RI: Seaside waterfront communities are all the rage. Who’s buying – Emilio DiSpirito June 6, 2025

- Outdoors in RI: 2A votes, Charter Yachts, active summer programs, garden tours, aquatic weeds… June 6, 2025

- All About Home Care, with two Rhode Island locations, closing after 22 years in business June 6, 2025

- GriefSPEAK: Angel wings with footprints – Mari Nardolillo Dias June 6, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 6, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 6, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Why the rush to reopen schools?

by Richard Asinof, ConvergenceRI.com

It takes a coronavirus pandemic to get a new state health lab, but the larger, unanswered question is: where do children go to get tested today, in advance of schools reopening?

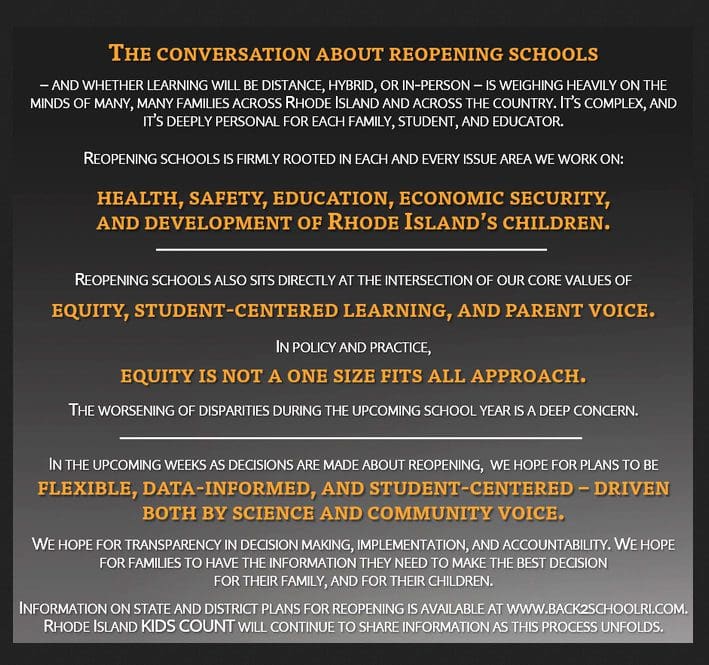

Rhode Island Kids Count tweeted out its thoughts about “The conversation about reopening schools” on Aug. 1, providing important context to how the decision will get made and who will participate in the decision making.

In case you missed it, last week, on Monday, July 27, with lots of public relations fanfare, Gov. Gina Raimondo announced plans to build a new $107 million state-of-the-art health laboratory facility for disease prevention and management, to be located on state land in Providence somewhere near the Wexford Innovation Complex and the Brown Medical School, with money to fund it coming from a new statewide bond to be approved by voters in November of 2020.

The decision to invest in the new state lab was precipitated by the determination made by R.I. State Treasurer Seth Magaziner that the state now had enough increased capability to manage more debt and could borrow more money in the form of voter-approved bonds. The proposed new facility is one of a number of initiatives slated to receive ramped-up investments through voter-approved bonds in 2020, including $40 million for affordable housing to support the design, development or repair of some 2,000 housing “units” across the state. [The urgent need for affordable housing, however, far outstrips this new proposed investment, according to the Building Homes Rhode Island status report released last week. If affordable housing is the best prescriptive medicine to cure health disparities, why not invest at least the same amount of money that is going toward the state health lab, instead of $67 million less?]

The new state lab is being positioned as the creation of a new economic hub for innovation and research – and yes, as a hedge bet against any future pandemics. The lack of proposed investment in the state’s public health infrastructure had been a glaring omission from the state’s strategic plan for the innovation economy, “RI Innovates 2.0,” released in January of 2020. [See link below to ConvergenceRI story, “What does public health have to do with future prosperity in RI?”]

Instead of “It takes a village,” perhaps the new phrase should be: “It takes a pandemic.”

The first hurdle the new state health lab will need to overcome on the road to being built is gaining approval from the R.I. General Assembly; the second hurdle will be getting approval from Rhode Island voters; the third hurdle will be coordinating the financing, choosing the actual land site, and then commencing the construction.

Translated, the earliest that the new state health laboratory would come on line would be sometime in the summer of 2022, if all goes according to the most favorable scenario laid out by Commerce RI Secretary Stefan Pryor.

Readiness is all?

The problem, of course, is that while the new state health laboratory promises to be a crucial investment in the state’s future public health infrastructure, with increased testing capacity, God forbid, to deal with “any future pandemics,” it is still two years away from opening its doors, at the earliest.

The future new state health lab will not solve the immediate, urgent crisis confronting Rhode Island: the lack of access to testing to the coronavirus pandemic, particularly for those Rhode Islanders who live on the wrong side of the tracks when it comes to racial, ethnic and wealth disparities.

Translated, here in Rhode Island, there has been a perceived lack of a culturally congruent response to the Latinx community in Rhode Island when it comes to testing for the coronavirus, according to a number of public health advocates. Some effort has been made to address these inadequacies, but have they been enough? [See link below to ConvergenceRI story, “Connecting primary care to emergency care in a pandemic.”]

The Dexter Street coronavirus testing site in Pawtucket, for instance, which had been cobbled together on an emergency basis, working through Commerce RI, Alert Ambulance Service, Collette Travel, and others, is now moving to a new location in downtown Pawtucket, beginning on Tuesday, Aug. 4, where its operations will be managed by the locall Health Equity Zone, according to Dr. Michael Fine, who told ConvergenceRI that he will no longer be involved in its operation.

Demand in some locations has been high. The coronavirus testing site being managed by the Open Door Health Clinic and the Rhode Island Public Health Institute at the Southside Cultural Center of Rhode Island, targeting the Latinx community in Providence, had been operating at capacity every single day it has been open during the first few weeks in July [until the recent heat wave forced it to curtail operations at its outside location in the Center’s parking lot].

For many essential workers in Rhode Island – and particularly for parents with school-age children, attempting to make plans and figure out how many balls in the air they must juggle to decide if their kids should attend online or in-person school in the fall, the difficulty in accessing testing and then obtaining the results, positive or negative, in a timely fashion, has emerged as the critical hurdle to any plans to successfully reopen the state’s economy and schools. [See link below to ConvergenceRI story, “A deadly experiment in Rhode Island?”]

Numerous public health researchers have weighed in to give their prognosis: “Realistically, we MUST control levels of community transmission of COVID-19 if we want kids & teachers in schools,” Dr. Megan Ranney, founding director of the new Emergency Digital Health program at Brown University, tweeted on Friday, July 31, citing three new research studies. “We may be able to send kids back, but we need PPE & regular, random testing of kids & teachers, whether in elementary, middle, high school, or college.”

Ranney continued: “But if we really care about kids’ health, let’s act like it. It’s not schools’ fault that we rely on them for far too much. Let’s think outside the box of ways we can do it all, instead of forcing families to decide [in high COVID-19 prevalence states] between food/work vs. infection/death.”

In response to Ranney, New York Times reporter Apoorva Mandavilli tweeted: “Don’t want to jinx it, but it feels like something has shifted in the ether, and people are finally accepting what some of us have been thinking & saying for months: Yes, kids can get infected, and yes, kids can transmit. Why would this virus be magically diff from all others?”

One of the five benchmarks in Gov. Raimondo’s school reopening plans seeks to measure “testing readiness.” It asks: “Do we have the ability to test all symptomatic [emphasis added] staff and students and on average get the results within 48-72 hours?” [Random testing of kids, teachers, and workers, as recommended by Ranney, is not included as part of the readiness benchmark for testing.]

A statement from Rhode Island Kids Count, tweeted on Saturday, Aug. 1, provided some critical context to the conversation around the reopening of schools in Rhode Island: “Reopening schools also sits directly at the intersection of our core values of equity, student-centered learning, and parent voice. In policy and practice, equity is not a one size fits all approach. The worsening of disparities during the upcoming school year is a deep concern.”

Translated, no amount of reassurances provided by the Governor from her pulpit at her weekly briefings at Veterans Memorial Auditorium and on her Facebook forums is going to alter the facts on the ground.

A state of dysfunction

Despite all the assurances by Gov. Gina Raimondo and her team that science and public health and safety for children and teachers will be the guiding principles governing the reopening of schools in Rhode Island, many parents are still not buying it, judging from the public responses. Many are not ready to jump off the proverbial diving board into a pool that has no water in it – with no plans in place for testing and no clear mandate on the wearing of masks.

As one parent told ConvergenceRI, “I’ll believe it’s safe to send my kids back to school when the Governor and her husband sign up to be substitute teachers.” Translated, the parent was saying: “You first, Governor.”

The blowback has been fierce, despite the best communications efforts undertaken by the Governor and her team to massage and manage the messaging.

In an interview WPRI’s Steph Machado aired on Friday, July 31, with R.I. Education Commissioner Angélica Infante-Green, the Commissioner admitted that the challenges around the logistics of reopening amid a public health crisis had been “a nightmare.” Buried in the story was an admission of the daunting reality: Rhode Island “doesn’t have enough testing capacity to test everyone for COVID-19 before returning to school,” as Machado reported.

Here in Rhode Island, which has done a markedly better job than many other states [Georgia, Arizona, Texas, and Florida] in coping with the COVID-19 pandemic, the decisions around the upcoming school year all revolve around the issues of trust and behavior. [At the most recent news briefing, the Governor warned residents that she had hit the pause button on Phase Three reopening, because “You are partying too much.”]

• In recent weeks, parents with sick children have said they have often encountered a maze of bureaucratic encounters in their attempts to arrange for testing and then having to wait for the results.

One family told ConvergenceRI about having to take their child to an emergency room to get tested after being frustrated, because they had been unable to schedule a time to get their daughter tested in a timely fashion, following a telehealth visit with their pediatrician. The first opportunity for testing had been more than a week away. [At the emergency room, which apparently had access to the Abbott testing device, the parents said they had received the results in less than 30 minutes; it was negative.]

Information about where to go for testing for children for the coronavirus is available, if you know where to look to find it. It does not necessarily mean that scheduling a test will be an easy task or that receiving test results in a prompt fashion will occur.

The official guidance from the R.I. Department of Health is that parents seeking coronavirus tests their children should first consult with their pediatrician. For families without primary care providers, there are respiratory clinics offering on-site evaluation with COVID-19 testing. A complete list is available online at the R.I. Department of Health website.

There are two respiratory clinics that only see kids and accept outside patients, according to Joseph Wendelken, the public information officer at the R.I. Department of Health. They are Just Kids RI Sick Care in Cumberland, 401-658-2273, and PRIMA Pediatrics also in Cumberland, 401-33-5201.

• None of the 10 CVS Pharmacy drive-up sites listed on the R.I. Department of Health website for coronavirus testing accept pediatric patients.

• Primary care practices and community health centers, many of which have ongoing contracts to process tests through a local lab that then sends the samples to national private laboratories for analysis, report that the increased testing demands from Florida, Texas, and Arizona, where coronavirus infections have risen exponentially, have overwhelmed the national capacity of private laboratories, resulting in delays of getting results back of 10 days or longer.

Accessing coronavirus testing can depend on wealth and privilege factors. In preparation for students returning to campus in the fall, Brown University has been engaged in a summer pilot program, according to an excellent Brown Daily Herald story written by Olivia George and published on July 30. George conducted an interview with Russell Carey, Brown’s executive vice president for planning and policy, about COVID-19 testing procedures.

Under the summer pilot testing program, in which COVID-19 tests had been provided at no cost to the individual being tested and did not require any form of insurance, with nearly 1,200 tests conducted and fewer than five positive tests during the first month of operation, one of the big takeaways, according to Carey, was the fact that “our wait time has not been good.”

As a result, Carey said that Brown had contracted with a new lab partner that has been returning test results within 48 hours. The university, according to Carey, is in the process of finalizing a relationship with the Broad Institute, in order to facilitate a 24-hour turnaround on testing results from the time the sample is received.

Translated, Brown University’s financial resources have enabled them to push for and receive a 24-hour turnaround on testing results for students and faculty, while community health centers remain tethered to a testing infrastructure that appears to be collapsing under the weight of increased demand.

• Smaller pediatric practices have been slammed financially by the coronavirus pandemic, because the practices make good profit margins on the annual wellness visits and back-to-school exams as well as yearly vaccinations, given that the volume of such visits have shrunken, according to a local physician. [A delegation of providers met with the Governor a few weeks ago to urge her to get behind efforts to promote such visits, according to sources.]

• The high rates of coronavirus infections in urban communities with high density housing and large immigrant populations have exposed the way in which health disparities have been made visible by the pandemic – and the way that those disparities also play out big time in the difficulties in access to testing by children.

The whole truth?

It was a remarkable moment, then, to listen and watch Gov. Raimondo, Commissioner Angélica Infante-Green, and Dr. Nicole Alexander-Scott, director of the R.I. Department of Health, “present” the facts at the Wednesday, July 29, news briefing around the process for school reopening plans in Rhode Island, with the stated, explicit goal to resume in-person classes on Aug. 31.

The Governor touted her leadership in reopening childcare facilities in Rhode Island as an example of a precedent for the reopening of schools. She talked about how an outbreak of coronavirus at an unnamed daycare facility that had been dealt with swiftly and contained, promising that a similar kind of response could be expected if such a situation occurred at schools when they reopened.

The tone was one of reassurance – saying that the health and safety of teachers and students would come first in any decision regarding the opening of schools. A team of public health experts was announced to assist the Governor’s team in drawing up plans regarding the reopening of schools.

The next day, on Thursday, July 30, on the weekly Facebook forum featuring the Governor talking with public health experts, Yale School of Public Health epidemiologist and pediatrician Dr. Sten Vermund said: “We’re going to need to have some investments in our schools. We teachers can’t do it all by ourselves,” as reported by WPRO’s Steve Klamkin. Vermund then opined that children would be able to handle the coronavirus well, but the danger is that they can pass it on to teachers and other adults who are at greater risk. Really?

Calculating risk

All the metrics, all the opinions, depend on how the risk is being calculated. From an epidemiological point of view, it would be possible to have an academic discussion on how best to calculate risk in order to better understand the parameters.

Ashleigh Tuite, an epidemiologist based in Toronto, analyzed the risks involved by attempting to answer the question: “How much community transmission is too much to reopen schools safely?” Her answer, offered in a thread of tweets: “It depends on your confidence in schools to control/prevent spread, and your own risk tolerance.” Tuite continued: “To use the whatck-a-mole analogy, it’s easier to keep COVID-19 under control in schools if there are fewer moles to whack.”

But, on the ground, risk becomes an emotional discussion, particularly when it is your children or your parents or your own life that is at risk and being threatened.

Transparency?

The Governor and her team are under no obligation to tell the whole truth to the public listening and to the reporters attending the weekly news briefings about what may actually be happening on the ground in Rhode Island, whether at nursing homes, at schools, or in hospitals. In the last few months, the Governor and her team have become experts in managing, massaging and controlling the flow of information, at the same time building up a strong reputation for the Governor with the national media about her effectiveness in managing the pandemic.

In many cases, as it should be, it is up to the reporters to dig out the information and then challenge the Governor with the facts. As an example, the Governor did not share information about the state contract with the Boston Consulting Group unitl a reporter [Kathy Gregg at The Providence Journal] stumbled across the information and published the details.

Hypothetically, let’s ask the question the way that the Continental Op, Dashiell Hammett’s fictional private detective, might have done so: Suppose that, on Wednesday, July 29, the date of the last news briefing, the Governor and her team knew about a suspected outbreak of the coronavirus, with the potential for hundreds of children to be exposed, at a childcare facility, once again, hypothetically speaking, that was located in Barrington, in East Greenwich, or in West Warwick.

What would be the obligation of the Governor and her team to share that information with the public? When would the Governor be willing to share it? And, what details around testing results would they be willing to share?

Unless a reporter happened to stumble upon the story, how would the details become known? In a relative uptick in the statistics about the number of cases, days or weeks after the outbreak occurred?

And, given the potential urgency of getting the test results in a timely fashion, in less than 48 hours, how might the R.I. Department of Health intervene?

Here is a link to the complete story: http://newsletter.convergenceri.com/stories/why-is-there-a-rush-to-reopen-schools,5908

Richard Asinof is the founder and editor of ConvergenceRI, an online subscription newsletter offering news and analysis at the convergence of health, science, technology and innovation in Rhode Island.