Search Posts

Recent Posts

- In the news: Quick recap of the week’s news… 6.14.25 June 14, 2025

- Drowning in corruption in Bonnet Shores: Hundreds sign petition. No action by lawmakers. June 14, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 14, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 14, 2025

- Burn with Kearns: Train smarter, not harder. Multi-use fitness tools – Kevin Kearns June 14, 2025

- Out & About in RI: Miriam Hospital Gala raises over $890,000 June 14, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

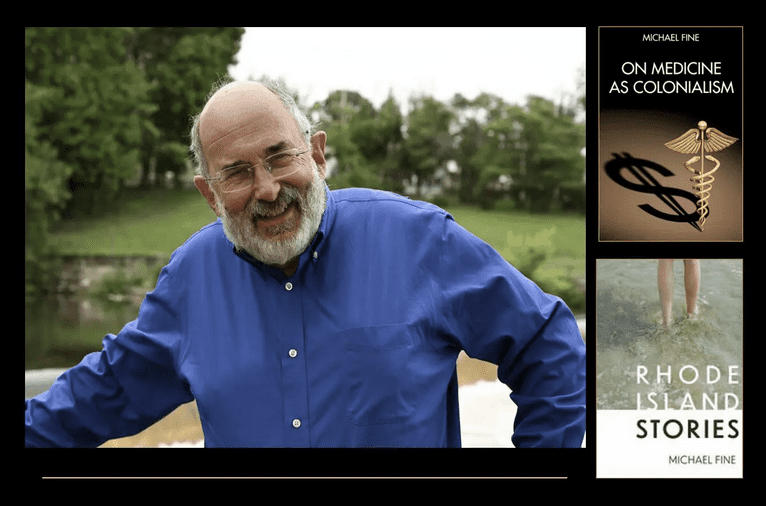

What To Do With Dead Squirrels. A short story by Michael Fine

By Michael Fine, contributing writer

© 2025 by Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

I didn’t think much of it when Vern started shooting at the squirrels.

You got to understand that I don’t take to shooting animals. Animals are like people, more or less. They got lives and they got only so much time on this earth, and maybe they even got little spirits in them, who knows? And they live in the woods or in the bushes and don’t bother me much, so I think we should let them pretty much alone. Out of sight, out of mind. The raccoons and the groundhogs and even them little bunnies come after the garden, so we got us a dog and that dog keeps those creatures away. The birds and even the bugs and the fishes that live in the sea – they all have their own little lives, and I think we need to let them be. Live and let live. They make life more interesting.

But them squirrels, they are a problem. They climb over everything and get in everything. They are in the trees and on the ground and they jump from the trees to the roof and gnaw on the siding of the house itself. They want to get in where it is warm and make their nests, like they don’t have enough trees to make those nests in, and they chitter and they chatter — they chase each other all over the place and cavort like they got nothing else to do and nothing to be ashamed of, and they make babies like nobody’s business so there are thousands of them, even though they get run down in the street by cars and hawks come and pluck them off the branches of trees like they was fruit, from time to time.

This all came to a head when they got into the attic of the garage and made themselves a nest there. Now I wouldn’t have minded that much myself, but Vern has his shop there and those squirrels made themselves an awful mess, with leaves and twigs and old pink house insulation and such, and with their droppings, which got everywhere.

Then those little buggers started chewing on the siding of our house. Five-thirty in the morning when we was trying to sleep. Scratch and gnaw. Scratch and gnaw, the sound a person might make when trying to rip the shingles off a roof, or even worse, the sound a person who got buried while still awake might make, trying to claw his way out of his coffin.

They made a terrible racket. I’d get up or Vern would get up and we’d go over to the window that looked out on the garage and bang on the wall next to it. Them squirrels would quiet for a moment. Then we’d go back to bed. But as soon as we did, them squirrels would be back, gnawing on the siding again. Scratch and gnaw. Scratch and gnaw. Them squirrels wouldn’t quit until one of us went outside and threw rocks at them, us standing on the patio in our bathrobes at dawn.

No wonder the neighbors look at us funny.

So Vern got himself a pellet gun and he took after them squirrels.

“Can’t you get some kinda fake owl or something and scare them away?” I said.

“No squirrel is gonna be put off by any plastic statue of an owl,” Vern said. “They are smarter than that. Unfortunately.”

“How about some rat poison?” I said.

“Too slow. Anyways I put them bait boxes on the ground. The mice and the voles and the rats and chipmunks eat it. And they die off. But not the squirrels. They don’t go into no bait boxes on the ground.”

“Traps. You could trap them,” I said. “They got them steel cage traps. Have-a-heart. The kind that catches them alive and unhurt. Use peanut butter for bait. “

“What then?” Vern said. “Once I trap them, what then? I could drown them in a bucket of water, I suppose. But that feels like torturing them. I do want them gone. But I don’t need them to suffer. Anyways they’d be just as dead if I own up and straight out shoot them. I could trap them and then drive them out to a state forest and let them go. But it is illegal to do that, and besides, that means driving every single squirrel ten miles, and I don’t got time to do that. Besides, when you move squirrels that way they get disoriented and just die or the foxes and hawks get them, because they don’t know where to hide, so they is dead anyway, and if they survive they’ll like as not find their way back here, and then I got to start all over again. Naw, I got myself a little pellet gun, and I aim to solve my own problem my way.”

And that’s when I lost Vern, at least for a while.

Vern got himself a lawn chair and he sat out under a tree with that pellet gun.

Now a pellet gun don’t make a sound like a rifle. It’s a sound more like a slap than a boom. Two metal plates hitting one another. A book dropping on the ground. A beavertail hitting the water, if you ever heard one of those. Vern sat out there from morning to night, as soon as the sun got warm enough to sit under, and then until dark, like he had nothing else better to do.

He wasn’t no good with that pellet gun at first. I’d hear Slap! Slap! Slap! and then nothing for a while. Then Slap! Slap! Slap! again. But soon he settled himself down and learned to aim right, and pretty soon it was Slap! Hiss! then nothing. Then after a few minutes Slap! Hiss! again, as the squirrels he shot fell into the leaves piled up under the trees.

I had no idea just how many squirrels there actually were in our neck of the woods. I thought he’d kill two or three, and that would be that. But those squirrels, they kept on coming, and Vern stayed out there and kept on shooting them down. Slap! Hiss! Slap Hiss! You’d of thought those squirrels would have learned to stay away from Vern and our place when they saw their brothers and sisters get shot down in cold blood, but apparently squirrels is just like people, and they don’t never learn from watching what happens to somebody just like them, or they think they are invincible or something. No humility, that’s what it is. Them squirrels, they kept on coming and Vern kept shooting them out of the trees. Two weeks. Three weeks. Four weeks. Hundreds of them poor critters, which Vern just piled up next to a big maple tree.

Well, it took a couple more weeks but Vern finally run out of squirrels after all. There’d only be one Slap! Hiss! an hour. Then only one or two a day.

Then the weather turned cold, and Vern folded up that lawn chair and put his pellet gun in the corner of the living room and settled himself back in his easy chair for the winter.

But there was still that pile of dead squirrels, sitting under the big maple tree next to the garage.

They stank, of course.

I assumed that one day after he was finished shooting at those squirrels, Vern would pile them up in the wagon he has that he pulls behind the ride-on lawn mower and haul them out into the woods and dump them. And that would be that.

But Vern has a stubborn streak. And I reckon he was still mad at them squirrels for chewing on our house. So he just left them there to rot.

And rot they did, because dead squirrels don’t go away by themselves.

I waited a week for Vern to come to his senses. Ha! Senses to say the least. The smell of them squirrels was awful bitter. It bored into you and stayed with you. It was so thick you could taste it with your eyes. It sat in the back of your nose and mouth and felt like it wormed its way into your brain. Couldn’t sleep because of it. It woke me at night, every night, if and when I did fall asleep. And it got worse with every passing day.

But Vern just sat there, in his big red easy chair in the den with the TV on, looking like he was pleased as punch. Sittin’ on the catbird seat. In charge of the world. Smarter than anyone and everyone else. Cause he had solved the squirrel problem, see, once and for all.

“Watcha gonna do with them dead squirrels?” I asked him one morning when there was a mist, when the air wasn’t moving and the stink was so thick you could almost see it.

“Whatcha say?” he said back, yelling like he didn’t hear me, though I was right there in the room with him.

“The squirrels. Them dead squirrels. Whatcha gonna do with them dead squirrels?“ I yelled back.

Would you believe that that man turned his face away from me and went back to looking at the TV like I wasn’t there?

“The squirrels! You got to get rid of the squirrels now that you’ve blown them all to kingdom come,” I said.

“Fool woman,” he said. “I don’t know what the hell you are talking about,” and he got up and left the room, got in his car and drove off.

It takes a woman every time. Men don’t measure up. They got issues.

So one morning in late October after the leaves had come off the trees, maybe the last bright and sunny day before winter, I suited myself up and took matters into my own hands. You can’t depend on no man no more. You got to watch out for yourself.

I put on three layers of clothing. Long underwear, an old sweatshirt, an old pair of jeans that had holes in them, and then a yellow rainsuit, what people used to call slickers, that I found up in the attic. If I could have got them I would have wore one of them thick white suits that beekeepers wear, or one of them hazmat suits you see on TV, but I didn’t have nothing like that nearby. I put on a hat and three different masks left over from Covid and one of them plastic face shields that the ladies down to the health clinic used to wear when they was working in Covid, and I put on a pair of goggles like men use when they is working on a car and grinding, the kind that stops little shards of metal from getting in their eyes that you both can and cannot really see through. Then I put on three layers of gloves – the latex gloves they use in that health clinic, a pair of my old gardening gloves and then a pair of bright orange rubber gloves I once got on sale at the Job Lot, the kind that come almost to your elbows, that people use to clean out ovens. Then I put my feet and bottom into a pair of green rubber waders with straps that come over your shoulders that Vern had left over from when he used to go fishing, back when he still had some get up and go and didn’t spend all his days sitting in that big red chair in the den watching TV, when he’d go for trout in the springtime, long ago.

I must have looked quite a sight, but I didn’t care. You have to do what you have to do when you have to do it. Sometimes you just can’t take no for an answer, even when you are talking to yourself.

I charged out into the daylight.

I got Vern’s bright yellow ride-on mower from the garage and fired that baby up, then drove it back behind the garage where he keeps the little trailer that goes behind it, hooked that trailer up, and then drove it to under the tree where the dead squirrels was at. Took me a pitchfork from the garage. Sometimes life isn’t pretty but a woman has to do what a woman has to do.

Them dead squirrels was laying in a matted-down grey heap of eyes and teeth and bushy tails. There was a cloud of flies buzzing around. The sun in late October stays low in the sky, and glints in your eyes when you are working if you aren’t careful, so I kept my back toward it.

It was a sad thing to see those little buggers laying dead like that. They was past starting to rot. The skin had pulled back from their little faces, so their teeth stuck out, little white buck teeth in a kind of ghoulish grin, and their little ears were pulled back. Some of their eyes had been pecked out by birds or eaten by the ants, so they looked dazed and vacant, which was no surprise. Given that they were all dead and all their parents, brothers and sisters and grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins were dead as well.

But there was no hesitating. I jumped in and did what needed to be done.

The pitchfork turned out to be the right tool. I could lift four or five of them dead squirrels at once and toss them into that little trailer that was behind the yellow ride-on mower. They made a thump as they landed, a kind of plop, like something moist and soft landing on sheet metal, a sound that reverberated. That sound changed after the fifth or sixth forkful, after the bottom of the trailer was completely covered by dead squirrels. Then each forkful landed quietly, more like the sound of a heavy but slow rain falling on earth.

I sweated up under all those garments but I kept on. Wasn’t fun but it didn’t take but a half hour.

Then I leaned the pitchfork against the tree, fired up that ride-on mower and drove up the little hill behind the house and down the lane that connects our place to the conservation land and drove into that land maybe a mile, maybe a little more. There is a low place back there where people dump all sort of things, illegally of course – old tires, old washing machines, car parts, old sofas and mattresses – you name it. I backed that little trailer into that little valley, took the back piece off, pulled the dump mechanism and then pushed the front of the trailer up into the air, so all them dead squirrels slid off the trailer and into that junk heap on the conservation land. Then I dropped the trailer back into place, fired up the ride-on mower and drove off, thinking, good riddance to bad rubbish, and was pleased as punch I had done what I set out to do. At least somebody in this family is on the stick, I thought. At least one of us is willing to do what must be done.

Yup, maybe I could have got in trouble for dumping illegally on conservation land. But I didn’t care right then. The stink would be gone from our premises. Them squirrels would rot and return to the earth a whole lot quicker than them washing machines, car parts and whatnot. It’s a big country. People in Washington DC and other places do worse than what I just did every single day.

Came home. Washed the trailer and the ride-on mower down with the hose and put them both back where they belonged. Took the pitch fork from under the tree and put it back in the barn. Went out behind the house and stripped off all them clothes – the yellow slicker, the hip waders, that old sweatshirt and those old jeans — and put it all into a big black garbage bag, the kind people use for the leaves they rake up in the fall. I tied the top of that big bag into a knot and carried it to the street for the garbage men to pick up when they came through the following day.

Then I took a long hot shower.

You can’t just sit in the stink and let dead squirrels molder. Sometimes a woman’s got to act.

The fall wind blew cold that night. The dead leaves on the ground rustled. Some people turned on their furnaces. Other people put a fire in their fireplaces to chase the chill away.

The stink slowly dissipated.

Vern went off to bed about nine like usual. I stayed up, wide awake and full of energy. That was a surprise. My back and shoulders ached some, but I had a satisfied feeling, the kind that comes after a hard day’s work.

I’ll sleep tonight, I told myself. It’s about time.

Vern had left the lights on. He was snoring when I got into bed. I turned out the lights, got into bed, cozied up to the man despite everything, fell into a deep sleep, and figured I might sleep to near noon. I deserved to.

It was daybreak when I heard it.

At first I thought I was dreaming.

I roused but then fell back to sleep.

Then the noise came again.

Scratch and gnaw. Scratch and gnaw.

___

Many thanks to Carol Levitt for proofreading, and to Lauren Hall for all-around help and support.

Please click here to receive Michael Fine’s monthly short stories and his new series, What’s Crazy in Health Care. Please invite others to join by sending them the link here.

Information about Michael’s books, stories, posts, talks and performances is available at www.MichaelFineMD.com or by clicking the link here. Join us!

___

Read more short stories by Michael Fine, go here: https://rinewstoday.com/dr-michael-fine/

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor in Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.