Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Real Estate in RI: Seaside waterfront communities are all the rage. Who’s buying – Emilio DiSpirito June 6, 2025

- Outdoors in RI: 2A votes, Charter Yachts, active summer programs, garden tours, aquatic weeds… June 6, 2025

- All About Home Care, with two Rhode Island locations, closing after 22 years in business June 6, 2025

- GriefSPEAK: Angel wings with footprints – Mari Nardolillo Dias June 6, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 6, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 6, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

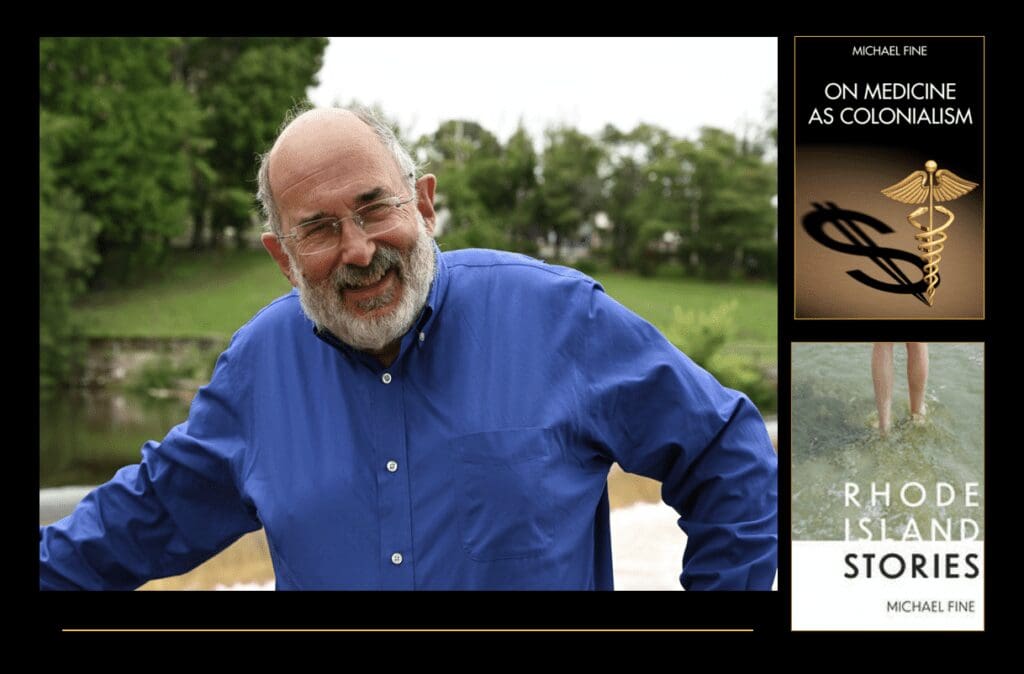

What Devon Knew: A short story by Michael Fine

By Michael Fine, contributing writer – © 2024 by Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

What Devon Knew

What Devon knew when he opened for the day.

He knew he had a roofing business in Pawtucket, a wife, a daughter and a granddaughter. and he knew that he did what he needed to do to survive:

He knew that his daughter, Esti, had a new job and was doing well for herself down there in Cornwall, New York.

What Devon didn’t know when he opened that day.

He didn’t understand what Esti actually did.

What Devon knew

He knew Esti went to meetings. He knew she had a Ph.D. in biomechanical engineering.

What Devon didn’t know

Devon didn’t know exactly what biomechanical engineering was. Something about making devices and machines to help take care of sick people. He didn’t know where they money came from that was used to pay Esti so much money.

What Devon knew

He knew Esti bought a car that cost more than he paid for his first house. A Porsche SUV. He knew she bought a house. A condo. In Cornwall, New York. With a two-car garage.

What Devon didn’t know.

Devon didn’t know what Esti wanted the second garage for.

What Devon knew

He knew Esti had kicked Yohanon out of the house.

What Devon didn’t know.

He didn’t know who would take care of the kid. Who was two-and-a-half.

What Devon knew

He knew the kid’s name was Clarissa. He knew Clarissa was his granddaughter. He knew he could drive to see her and Esti. He knew Esti was too busy to drive north to visit her mother, was a nursing home now. He knew Evelyn, Esti’s mother, had had a stroke. Many strokes. He knew she recognized him. And Esti. More or less. He knew he visited Evelyn every day after he closed the shop.

What Devon didn’t know

He didn’t know for sure if Yohanon was Clarissa’s father. He thought Yohanon was Clarissa’s father. But he couldn’t be sure. Life is more complicated than it used to be.

What Devon knew

He knew Esti met Yohanon when she was in high school. And working after school and weekends, because they all worked afternoons and weekends in the shop. He knew Yohanon was a kid but twelve years older than Esti. He didn’t think much of it then. He knew Yohanon drove the van. And Yohanon carried bundles of shingles up to the roof. On a ladder. On his back. The heavy work. He knew Yohanon didn’t speak much English. But Devon didn’t care what language they spoke, the boys and the men who worked for him. He cared only about whether or nor they showed up on time, most days, and did what they were told to do. That they didn’t talk back and didn’t steal. Or that he didn’t catch them stealing. Because everybody steals. One way or the other. He knew that.

What Devon didn’t know.

He didn’t know what Esti could possibly see in Yohanon. There were five guys who worked in the shop. Yohanon wasn’t particularly smart or particularly good looking. He did have some attitude though. He acted like he knew everything. Like he was afraid of nothing. Maybe because he wasn’t smart enough to know what to be afraid of.

What Devon knew

Devon knew that Esti was smart as a whip. That she was way smarter than he was. He knew she was hot. Though a father doesn’t say that to himself about his daughter. He knew Esti’s mother wasn’t smart enough or organized enough to teach that girl life lessons. Life lessons about men and relationships and so forth, because neither Evelyn nor Devon had ever figured any of that out for themselves. Devon knew he should have warned Esti. Or told her to stop. But you can’t ever warn anybody about love or sex. Or they don’t hear you. Still, he knew he should have done more than he did. But by then it was too late.

What Devon didn’t know

Was when and where. He hadn’t seen it start. In the shop? In the basement? In a car? In a van? He heard the other boys in the shop snicker and turn away when he came into the warehouse or the basement and turn away from him when they saw him come into the shop. He didn’t know why at first.

What Devon knew

Was that nothing good could come of Esti being with a guy twelve years older who barely spoke English and was probably illegal. That Yohanan had no idea what he was getting into either.

What Devon didn’t know

Was that this would turn into a thing which didn’t make sense. That Esti would start staying out all night. That Yohanan would start showing up in Devon’s house in the morning. That Evelyn would run him off. That he’d return in the middle of the night because his skull was thicker than it looked, and he didn’t care what anybody said. That Evelyn would get them a restraining order. That Esti would move out to be with Yohanan. That summer. Before she went to college.

What Devon knew

That Esti was going to college a thousand miles away. Which was a good thing. That Yohanan would never follow her there. It was cold there. No one there spoke Spanish.

What Devon didn’t know.

That Yohanan wouldn’t show up for work a week after they dropped Esti off at college. That he would follow Esti to college and live in her dorm room.

What Devon knew

That Esti would get tired of all the drama. And kick Yohanan out of her dorm room.

What Devon didn’t know

That Yohanan would come back to Pawtucket. And ask for his old job back. No apology. No excuses. Just show up and say he was ready to work. He had balls, that Yohanan. A thick skull. No shame. And Devon thought, I need good workers. They pay the bills. Bygones can be bygones.

What Devon knew

Or thought he knew was that the papers Yohanan showed him were fake. All his guys had fake papers. Those papers protected Devon, more or less. No judge would convict him if he showed them copies of papers, even if the papers were fakes. And made it so those guys didn’t give him any shit. Because they knew and he knew he could always call ICE on them. Everyone understood everyone else. Devon knew that’s the way the world works. He knew Yohanan didn’t give a shit. Which meant one of two things – either Yohanan would do well in life, which was unlikely, because Yohanan wasn’t as smart as he looked. Or that he’d die young or drunk or be shunted to the side of the road, in this world where there isn’t really any room for people who aren’t smart or good looking. Or who aren’t connected.

What Devon didn’t know

Was how much trouble there would be in Yohanan’s life. How much trouble Yohanon would cause. He seemed like a little snitch. A nothing. Emphasize little.

What Devon knew

Was that Yohanan moped around like a lost puppy. That he started hanging around Devon like there was a question he wanted to ask. That Devon ignored him, because Devon didn’t want to hear it, because Devon was done with Yohanan, just done, and wanted nothing to do with him, and was glad that Esti had kicked Yohanan out. Yohanan could show up to work. He’d get paid on time, if he showed up to work and did what Devon told him to do. But that was it. No special favors. No fireside chats.

What Devon didn’t know

Was that Esti would come home for the summer. And work in the shop. And that she and Yohanan would start up again. Which made Devon mad and Evelyn madder. What had Devon been thinking? Why did he take Yohanan back? What was Esti thinking?

What Devon knew

Was that what Esti was doing wasn’t thinking. Girls like that, people like that, they don’t think. Their organs think for them. Or something. Their urges and their wants and their hormones move them around like pieces on a chessboard.

What Devon didn’t know

Was what hand is moving them and us around on that chessboard. When people do things that don’t make sense.

What Devon knew

Was that Esti had enough sense to use protection. Her mother saw to that. At least that. Devon checked and double checked. Esti being with Yohanan was trouble enough. She didn’t need and he didn’t need and they didn’t need no surprises.

What Devon didn’t know

Was that Esti would go back to college, and Yohanan would try to go with her, but that she’d kick him out again, and that he’d come back to Pawtucket again looking for his job back, his skull still thick, but now he was like a wounded animal hit by a car, skittish and small, with most of that bravado gone. Most of it. Devon didn’t know that it took Yohanan all the moxie he had left to show up in the shop again but Devon didn’t care. He just fired Yohanan’s ass, which he should have done a long time ago. Well not fired. No openings. Not for you. Never again. Good riddance to bad rubbish.

What Devon knew

Was that Yohanan went back to El Salvador. Where Devon figured he joined a gang or some such thing. And no one would ever hear from him again. Thank God.

What Devon didn’t know

Was that Esti couldn’t leave well enough alone. Why the hell weren’t one of them college boys good enough for her? Or a few, if that’s what she wanted?

What Devon knew

Was that Yohanan showed up again the following summer. And before long he was coming out of Esti’s bathroom in the morning.

What Devon didn’t know

Was that Yohanan was even more stuck on Esti than she was on him. That she didn’t have what it takes to stay away from him. And that he couldn’t get her out of his head. He didn’t know how having someone like Yohanan hanging around her, watching her every move, made her feel like something more than she was.

What Devon knew

Was that Esti was even more than she thought. That she was still way smarter than Devon was, and seemed to get smarter by the minute, if book learning counts for anything. Her stupidity about Yohanan aside, that she could learn anything and be whatever she wanted to be – doctor, lawyer, rocket scientist, genius computer geek – and that she way eclipsed her father and mother in smarts. Devon knew. Esti had no idea.

What Devon didn’t know

Was that Esti would get pregnant. After she came home to go to MIT for graduate school. And keep the kid. And Yohanon would hang around like a lap dog and cook and clean and take care of the kid while Esti was at work.

What Devon knew

Is that each child makes her or his own luck.

What Devon didn’t know

Was that he would fall for the kid, despite himself, and completely forget that the kid had a father, and who the father was. That Evelyn would have a stroke six weeks after Clarissa was born. At 59. Which sucked, really sucked.

What Devon knew

Was that Esti would graduate from MIT and have a brilliant career. That she would get job offer after job offer. That her value would mushroom during the pandemic, when there was huge demand for biomechanical engineers. That Esti herself would be a clever negotiator and find ways to play one company against the other. That she would be brilliant as a biomechanical engineer, whatever a biomechanical engineer is, and soon lead teams and give Zooms which hundreds of people would attend. That she would invent things. Write papers. Give Ted talks. And have hundreds of followers on social media.

What Devon didn’t know

Why giving conferences, leading teams and having hundreds of followers matters. He didn’t know how Yohanon could ever keep up with Esti. Or why Yohanon mattered to Esti, when there were hundreds of other people who wanted at her, some of whom were men, though Devon suspected that whether they were men or women didn’t matter anymore. To anyone.

What Devon knew

Was that Clarissa would become a very beautiful little girl, who learned to walk and then to talk, a few words at a time. That he saw Clarissa mostly on Zoom or Facetime.

What Devon didn’t know

Was what Clarissa smelled like. Was what Esti was thinking. Was what Yohanon was thinking. Was how much Yohanan had come to dote and depend on Esti. And how much he has come to love his little daughter, who he was bringing up.

What Devon knew

Was that Yohanon didn’t really have much else going for him. He could operate a forklift. Drive a car. Lift boxes and bundles on his back. Work a nail gun. Walk on a roof. But that was about it. His English existed. Sort of. But he had no future in a country that segregated the rich from the poor. Where you need big money to have a decent life. Where half of most people’s income goes to rent, because no one can afford to buy a house anymore, because a house costs six times the average annual income, not twice, like it used to. Where schoolteachers who went to college and have master’s degrees have second jobs and most work summers to make ends meet. But roofers and laborers, bartenders and waitresses, Uber drivers and Amazon drivers and post office clerks and mail deliverers, not so much.

What Devon didn’t know

Was that Esti was about to kick Yohanan out again. That Yohanon would move back to Pawtucket because he had no place else to go.

What Devon knew

Was that he himself was done with Yohanon, just done. Yohanon had no business messing with Esti in the first place. Hot shot. Legend in his own mind. Thought he could do what he wanted and take what he wanted. Thought he could be in the bathroom in Devon’s house in the morning like that, acting like he owned the place. Thought he could hit on a high school girl like that, who didn’t know better. Turn-about is fair play. That what goes around comes around.

What Devon didn’t know

Was that he would find Yohanon in a sleeping bag behind the dumpster at the shop because Yohanon had no other place to go. That he would feel something for the guy, feel sorry, whatever. That he’d say, don’t sleep in the parking lot. Come and sleep inside, in one of the storerooms, next to the toilet. And he’d give Yohanon his job back. And feel stupid for doing it. But Yohanon was his son-in-law, see. Technically, anyway. And you don’t just abandon people. Don’t just throw them away. Regardless of what Esti did or who Esti was.

Not that Devon’s life was so great. Evelyn was in the nursing home now, unable to speak. Devon was seeing Esti and Clarissa only on Facebook and Zoom. And still working twelve hours a day at seventy-two years old. Six days a week. Bills to pay. It is what it is.

What Devon knew

Or quickly learned, was that Yohanon was circling the drain. Bags under his eyes. Head down all the time. Work in the same clothes day after day. Devon was pretty sure he slept in them as well. The shop floor outside the storeroom where Yohanon slept was covered in pizza boxes. Which Devon picked up and threw in the trash once a week, because he couldn’t stand to give poor Yohanon a hard time, as much as Yohanon deserved it. Couldn’t Esti send him some money? Not that he deserved one cent. So that Yohanon could live like a human being. But Devon knew that Yohanon had a little money from his paycheck. Not that he was coming to work every day. Somedays he just stayed in that storeroom, on the cot that had been there for years. Devon knew there was no natural light in that storeroom. It was just no way for a human being to live. But Yohanon probably couldn’t afford a real apartment on his own now, not on what Devon paid Yohanon or any of the other guys. Some of the other guys shared apartments with three or four other guys, until they got girlfriends. Not that Yohanon had the get-up-and-go it takes to look for a place. Or seemed to want to hang with other people. Not even Yohanan’s brother, who still worked for Devon, but you wouldn’t know they were brothers. Not now. The brother avoided Yohanon. Who was pretty much alone.

What Devon didn’t know

Was that Esti got herself a new boyfriend. Who had gone to Yale. Or that she was serving Yohanon with papers. To divorce him and be done with him once and for all. To start over. To trade up. The past is past. It’s gone. You can choose your destiny. Or not.

It had been three days. A long weekend. The sun was out and all the trees were in bloom. Devon slept late, for once. He didn’t go to the shop. He went to visit Evelyn late in the day, like he did every day on his way home, but she didn’t know him now. Sometimes, glimmers. But nothing now. Devon made himself pasta one night and one night took himself to a place up in Lincoln, a place with nice porches, but he sat at the bar anyway and got himself a steak. Nobody lives forever. Nobody ever got to seventy and said, gee whiz, I wish I had worked more.

But by Monday, Devon couldn’t take it anymore. I’ll just go in for a couple of hours. I’ll make sure the trucks are all set up for the morning.

The lights were on when he came into the shop, but it was quiet. Too quiet. Yohanan’s pizza boxes were on the floor outside the storeroom Yohanon slept in, like always. The boiler kicked on, a click and then a whoosh, as water and air started to move around inside ducts and pipes. It’s dank, in here, Devon thought. Too damned dank, stale and moldy. No human being should be living here. This is no kind of life. I wonder how Yohanon does it. And why.

“Hey,” Devon called out, to Yohanon. Just to let Yohanon know Devon was there. You don’t want to surprise a guy.

Nada.

Then he saw Yohanan’s back. Yohanon was just standing there in the doorway to the toilet, his head tilted, not moving. Then Devon saw the orange cord.

When it was over, after the police had come and gone, after the medical examiner had come and gone, long after Devon cut Yohanon down, using first a boxcutter and then a wire cutter to hack away at the orange electrical extension cord Yohanon used to hang himself with, after Devon picked up Yohanan’s pizza boxes and threw them into the dumpster, Devon stood there, in the dank shop, its walls made of lime green dust-covered concrete block, the fluorescent lights hissing, the boiler clicking on with its whoosh, so all you could hear was air and water moving, and then clicking off again, the whoosh and the air and the water pressure sounds replaced by a deafening silence, the sounds of the universe – distant airplanes far overhead, distant sirens, distant gears of distant trucks grinding out on Route 95, all deadened by the walls and the dank air.

Yohanon was gone. He had been erased. He was now nothing. The last memory Devon would have of him was of the purple blue of his face, of his head tilted at a weird angle, his neck broken. Gone. Absent. As if he’d never existed. Not even a shadow.

At that moment, Devon realized that he had loved Yohanon. Suddenly. Intensely. Mostly he hated Yohanon. He hated that Yohanon was such a smug asshole, at first. Hated that Yohanon had come on to Esti, who was only sixteen, by God, and didn’t know better. Hated that Yohanon kept showing up. Hated that Yohanon had the gumption to appear in the bathroom of Devon and Evelyn’s house in the morning. Hated that Yohanon wouldn’t leave Esti alone and that Esti wouldn’t leave Yohanon alone. Hated that Yohanon never had the sense to make something of himself. Hated that Yohanon was the father of Clarissa, Dervon’s only grandchild, and that Clarissa would forever have to wonder about this father of hers, who she might remember vaguely, and about whom there would be this huge secret, that her mother had kicked her father out and he had nothing so he hung himself and we just don’t ever talk about him. Hated that Yohanon had come back to Pawtucket and had been living in the shop, eating only pizza. Hated the pizza boxes. Hated the orange extension cord Yohanon hung himself with. Devon hated all that and more. Hated that he himself, Devon, had fathered Esti and let her live the way she did, taking up with Yohanon, who looked hot to her at sixteen but who she was so much stronger than; hated that what Esti had become even though she was a huge success; hated how that had diminished and ruined Yohanon, who never had a chance in Esti’s world; hated that he, Devon, had given rise to all this, and that he Devon, was living in a sad and tragic world of his own making.

But Devon mostly had loved that Yohanon existed, as much of a problem as he was. With his attitude, his absurd inflated ideas about his own importance, his weaknesses and his failure to be a man. Devon had loved Yohanon anyway, and never ever even once wanted or thought that Yohanon might kill himself like this.

But now Yohanon was gone.

Now Devon had nothing. There was nothing, and no one left.

Many thanks to Carol Levitt for proofreading and to Brianna Benjamin for all-around help and support.

Please click here to receive Michael Fine’s monthly short stories and his new series, What’s Crazy in Health Care. Please invite others to join by sending them the link here.

Information about Michael’s books, stories, posts, talks and performances is available at www.MichaelFineMD.com or by clicking the link here. Join us!

___

Read more short stories by Michael Fine, go here: https://rinewstoday.com/dr-michael-fine/

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor in Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.

Who is Grace?

From Dr. Fine: “Somehow, a fragment of a novel I’ve working on got inerted into the text. The correct version now appears here.” Thank you, Mr. Mikkelsen for being an astute reader!