Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Out and About in RI: Former Pawtucket Mayor Henry Kinch Tribute in Photos June 24, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather Forecast for January 24, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 24, 2025

- ART! Mark Freedman, first featured artist of Summer Art Shows at Charlestown Gallery June 24, 2025

- The Bellevue Hotel: Procaccianti Co. New Luxury Boutique Hotel Set for Newport’s Iconic Bellevue Ave June 24, 2025

- Mike Stenhouse, CEO of RI Center for Freedom & Prosperity, named into College Baseball Hall of Fame June 24, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Two visions of New York City – David Brussat

by David Brussat, Architecture Here and There, contributing writer

Two recent panels held by the Empire Station Coalition discussed rebuilding Penn Station in its original 1910 design and growing opposition to former Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s Empire Station Complex, which would clog the area around Penn Station with glass-box skyscrapers. The vicinity has already been declared a “blighted area,” placing 50 existing buildings at risk, including a dozen or so that are of historic importance. This plan must be stopped before the plan to rebuild Penn can make any sense.

A pair of essays, one in Crain’s New York by Alexandros Washburn, a former chief urban designer for New York City, and another in the New York Daily News by Josh Alan Friedman, author of Tales of Times Square, offer compelling cases for rebuilding the original Penn Station and against building “Houston on the Hudson,” as Friedman calls the Cuomo plan.

Imagine the difference between arriving in New York after Penn Station is rebuilt and arriving after the Empire Station Complex has been completed.

It is the difference that historian Vincent Scully evoked with his famous line after Penn Station was torn down in 1963: “One entered the city like a god; now one scuttles in like a rat.” The vast difference between the original Penn Station and the station we have today mimics the difference between Penn Station rebuilt versus getting stuck with the Empire Station Complex.

Of course, it would be literally possible to rebuild Penn Station and then surround it with glass towers. But that would be ridiculous.

***

The Penn Station that was demolished in 1963 was not quite the Penn Station that opened in 1910. As its owner went broke in the 1950s, Penn Central Railroad stinted on maintenance and installed “improvements,” especially an incongruous ticketing kiosk that detracted from the lines of the original. That is the station as recalled today by most who remember experiencing it as youths. The station as rebuilt anew would resemble the monument in its more salubrious form, before its grim and gritty final stages of faded glory.

Even in those final years, the sun’s rays still played with shadows on the fluted columns and carved embellishments of marble and granite inside and outside the station. Still, the aesthetic disjunct caused by layers of remodeling may explain why New York did not rise up in anger after the demolition was announced. Or maybe it was the difference between the power of social dissent then – burdened by the limits of a largely satisfied and obedient society – and now.

This post proposes that public opinion has much more influence today, and that forces aligning to block the Empire Station Complex and rebuild the old Penn Station can succeed where weak efforts to save the old Penn Station failed.

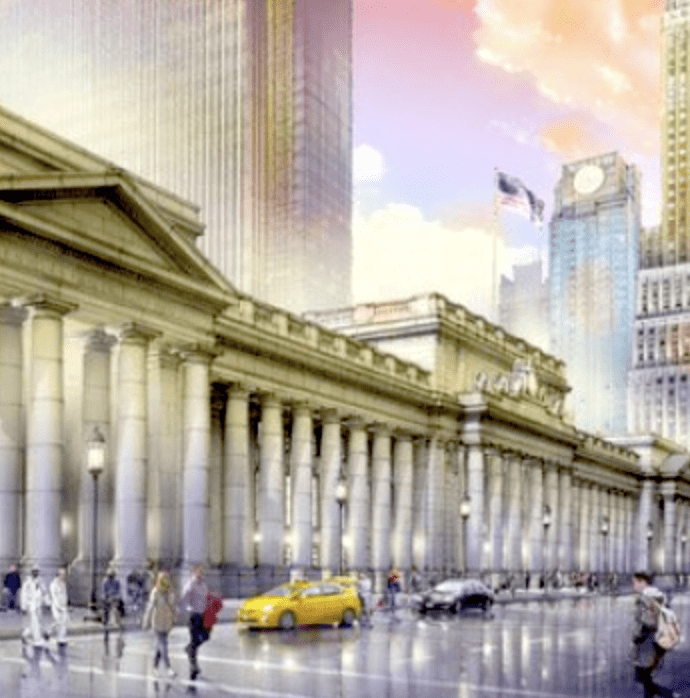

Sketch of Eighth Avenue facade of rebuilt station with outdoor cafes. (Cameron/Atelier & Co.)

Imagine, for a moment, that Penn Station has now been rebuilt. The practicality of the task as a matter of engineering defies the image most of us have of its impossibility. Almost the entire structure of the original station remains intact beneath existing retail and waiting/ticketing levels above the original tracks and platforms, including the load-bearing piers that uphold those levels and Madison Square Garden above. Original blueprints survive for the passages, chambers, utilities and other features in, out, and around Penn Station. With advanced computerized stonecutting equipment and digital techniques of ornamentation to cut and mold cast stone, there is no need to import thousands of stoneworkers from Italy. Washburn recently wrote in Crain’s that,

[t]o begin with, the station was not destroyed – it was decapitated. Gone are the soaring waiting rooms and the rows of columns, but all the guts remain. The entire foundation, every column supporting every piece of Penn Station is still there, as is the configuration of tracks. Most of the hard work of building the station is done. In many ways, you could argue that the easiest thing to do is to rebuild the station because you could do it without altering or affecting operations.

Imagine rising from track level to the vastness of a waiting room large enough to contain Grand Central Terminal in its entirety. Light floods through arched windows as you marvel at the monumental scale, and at embellishments near and far. You exit the station through a portal whose grandeur prepares you for ornate buildings, new and old, around the station, including those built or restored after the Empire Station Complex was killed.

The old standbys at risk have been rescued, including the Hotel Pennsylvania (also by McKim Mead & White), the Stewart Hotel, the Fairmont buildings, the Equitable Life Assurance Building, the Penn Station Powerhouse, the Gimbels Building with its beloved skybridge, and the churches of St. John the Baptist, St. Francis, and St. Michael’s. Preservation mooted the eviction of congregants and tenants, commercial and residential. Completing the classical ménage, but not at risk, is the old Farley Post Office next door to Penn Station, now the Moynihan Train Hall, by McKim Mead & White as well, featuring a colonnade as exalted as that of the original Penn Station.

Add to this the prospect of new buildings in traditional styles – chief among them a Madison Square Garden relocated, possibly, to nearby Herald Square and redesigned to reflect the second Madison Square Garden designed by Stanford White of MM&W that once overlooked Madison Square Park. Also imagine the host of parks, parklets and squares recently proposed to grace the station area by architect Richard Cameron, who years ago brought the idea of rebuilding the original Penn Station into public view.

All of this creates a sense of place undisrupted by the helter-skelter of styles erected higgledy-piggledy since World War II, which discombobulated the more gentle stylistic diversity of New York streetscapes long past.

Imagine strolling from the station through streets that pick up on the historical character of Manhattan in the decades before its glory faded. Unlike the sterile glass towers proposed by Cuomo, Penn Station and its surroundings, preserved and proposed, partake of an architectural language that neurobiological research has traced to human survival techniques going back hundreds of thousands of years. Science now explains why traditional building patterns are preferred by two-thirds to three-quarters of the public in the most recent survey by Harris a year ago over the currently favored establishment architectural language.

Imagine that. Architecture beloved by the public. What an idea!

***

In the Oct. 28 panel, Lynn Ellsworth of HumanScaleNYC described the currently dominant architectural language as a cage into which most design and planning officials and professionals have locked themselves. That is why – even in a nation where markets run by supply and demand are supposed to rule – the architects, the developers, the planning officials and all others involved in building cities never listen to the public. Instead, in New York, the nation’s leading city of commerce, a topsy-turvy dedication to “generic dead space,” as Friedman puts it, undergirds Cuomo’s Empire Station Complex: ten huge new glass skyscrapers between Hudson Yards and the Empire State Building, with at least one of them taller than the Empire State Building.

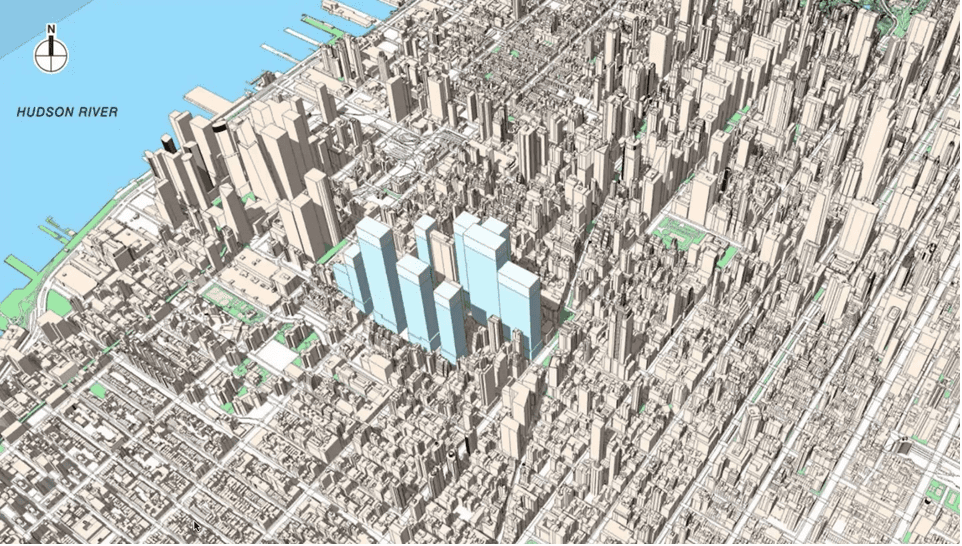

Axionomic drawing of Empire Station Complex buildout, in blue. (Draft EIS for Complex)

The official project description provided by the Empire State Development Corporation‘s environmental impact statement contains no attempt to describe the appearance of the proposed “transit-oriented commercial district.” It is as if the appearance of buildings has no impact on our civic environment. Only the square leasable footage envisioned by developer Vornado Realty Trust matters. Only the list of proposed building heights offers any feel for the eventual result. The heights, as listed, would range from the tallest at 1,300 feet on downward to 1,270, 1,130, 1,052, 1,018, 975, 936, 748, 664 and 235 feet. (The Empire State Building rises 1,250 feet.) The massing of buildings on the EIS maps is speculative, though perhaps not more so than the heights themselves.

With negligible warning from the project description, projecting the likely look of these behemoths nevertheless requires little more than your impression of the city’s two latest large development projects: Ground Zero and Hudson Yards. No doubt the dominant style of skyscrapers in the Empire Station Complex would follow these patterns, because the same firms that designed the glass canyons at both locations will be asked to submit requests for proposals that fit the latest architectural clichés. If anything, perhaps we may expect the ten towers to be dumbed down from the more abstract chaos of the two supposed exemplars.

As if to confirm this prediction, the EIS assessment of adverse impacts on neighborhood character concludes that “[t]he Proposed Project would not result in a significant adverse impact on neighborhood character,” adding:

The buildings are anticipated to have contemporary designs, with curtain wall façades of glass, metal, or masonry, which would be consistent with the urban design character of a number of the taller, more recently constructed buildings in the primary study area, such as 1 Penn Plaza and 2 Penn Plaza.

Which tells us precisely nothing. With so little to go on, considering that no building project has yet to receive an architectural treatment at this stage of pre-development, it is hard to imagine the urban design details along the streets surrounding Penn Station. Still, some aspects are predictable.

The ten buildings would be clustered up close around the north, south and east edges of Penn Station, reaching up in height to as much as eight times the height of the station (and arena) itself. The ten buildings would completely block the station and its environs from the sun at almost all day and almost all year. To walk out of Penn Station would force New Yorkers and visitors to confront a phalanx of towers antiseptic in aspect, producing dark shadows or reflective glare depending on the sun’s location in the sky. I could not find a wind study in the EIS, but clearly the building heights and the sheer, featureless architecture of the ten towers would cause a wind-tunnel buffeting of passersby.

***

Hudson Yards, Empire State Building, left, Madison Square Garden, center left. (Curbed NY)

Whether Penn Station is rebuilt in the original style or remodeled to apply lipstick to the infamous pig, the impact of the Empire Station Complex may be summed up as almost entirely negative. Only the developer, Vornado, would benefit from any of this. Proponents of Empire Station insist that the project would transform “substandard, insanitary” patterns of existing development into “cohesive, revitalized, modern” patterns to be inflicted upon the city without the say of its citizens. In either case, proponents often define these terms to mean the opposite of how normal people understand them. In other words, expect historic character, even at the nadir of its decline, to be replaced by a uniform sterility. The entire proposal is anti-urban in its essence.

Josh Alan Friedman sums this all up with frightening clarity in his piece for the New York Daily News:

In defense of the streets [around Penn Station], I say these grand structures deserve rehabilitation, not annihilation. The demolition of Penn Station is now acknowledged as New York’s greatest architectural crime. Bulldozing the remaining blocks around it would reopen the wound. …

I pray the entire Empire Station Complex is stopped cold. Private groups like ReThinkNYC and New Yorkers for a Human-Scale City have floated cheaper and better alternatives. Scrap the subsidies to Vornado, scrap the $16 billion in sketchy financing, dependent on the sale of air rights. Rebuild Penn Station as the center of a regional unified train network. Hopefully, one that would resemble the picturesque hub of a railroad, not a shopping mall. It is up to Albany to spare the city the insult of another hyper-developed, gentrified forest of glass towers.

Maybe, without our knowing it, the Empire Station Complex is already dead. How great would that be! If not, then perhaps with a new governor, and with more popular understanding of what the old governor has proposed as his parting gift for New York City, it ought not be too difficult to imagine the public rising up to replace a very bad plan with a very good plan.

The choice: Creative anti-urbanism or monumental civility. (Twitter)