Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Dr. Rosemary Costigan Named President of Community College of Rhode Island June 19, 2025

- RI Veterans: Did you know? 19.06.25 (Military Funerals, Job Fair, Benefits, Events) – John A. Cianci June 19, 2025

- East Providence First in U.S. to Equip All Firefighters with PFAS-free Gear June 19, 2025

- We Cook! Mill’s Tavern Saffron Bouillabaisse with Tarhana Lobster Jus June 19, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 19, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 19, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

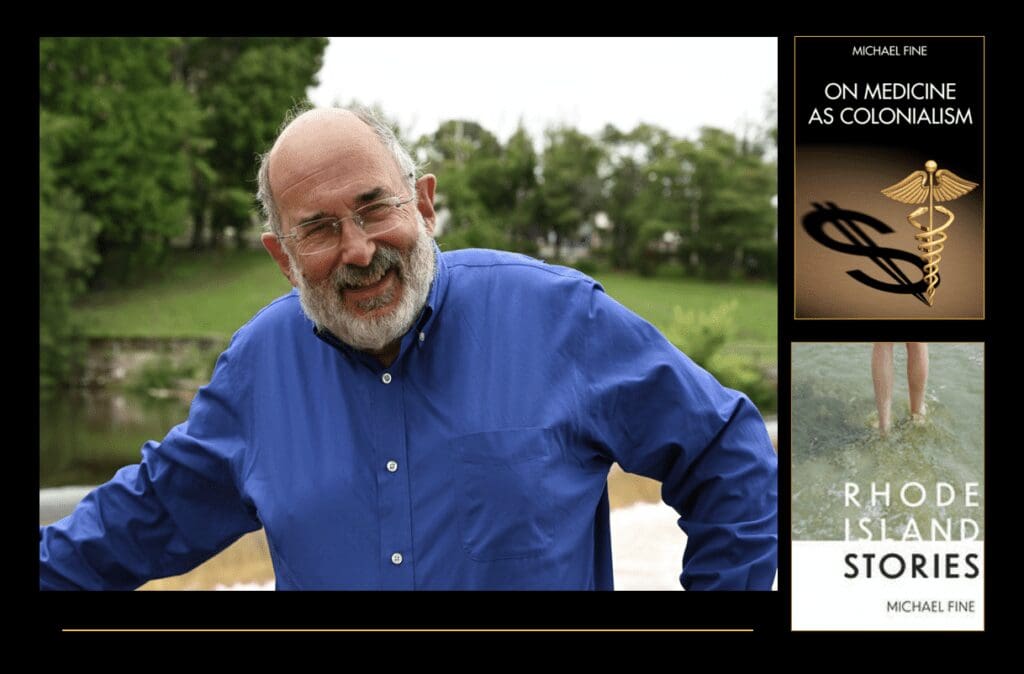

The Sadness of The Late August Light – a short story by Michael Fine

By Michael Fine, contributing writer

Copyright © 2023 Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

–

It’s hot, they said, in Arizona. Hot in Iran. Hot in California. Record heat in the Arctic. Oceans almost boiling in the Florida Keys. Glaciers melting. And so forth. But not too bad in Pawtucket, Rhode Island.

It was late afternoon. The biting part of the day, when the sun is high in the sky and burns you. It pinches your skin if you walk in it — that time of day had come and gone.

The sky was blue. There were big white clouds on one horizon. The light was red and golden. That light inflamed the colors of everything Jack could see, the ochre of the stone walls of the mill across the street, the white of the church tower with the clock in it across the river, the blue and green on the advertisements on the buses as they came and went on Roosevelt Avenue, the orange-red in the brick in city hall. All that glowed an unusual glow in the late afternoon light. It was better to be here, waiting for a bus, to be here than to be inside, despite the cigarette butts, the broken glass, the stink of urine and of diesel exhaust as the buses came and went.

Say what you want. He was still standing. Still walking and talking and speaking English. Still tough as nails. Tougher than nails. Tougher than almost anybody. You never turn your back, and you don’t take no shit from nobody. He had flattened his bid and he was still here to tell the tale. They thought they could kill him, but they failed. Don’t you tread on me, mutherfucker.

The bus to Kennedy Plaza was late. It creaked and grunted to a stop and then hissed, the steps on the passenger side dropping as the door banged opened to let people in. Jack paid his money and stumbled inside, reaching out to the stainless steel rails above him for balance as the bus lurched forward on its way, headed to the rows of seats at the back.

There were ads over the huge windows for health insurance, a CNA course and to make sure the LGBTQ people felt safe.

It was such a different world. In his day, buses had little windows and were dark inside. Funny, woven, yellow and brown seats. Now there is so much light that a man feels naked, like you might as well be outside, and all the LGBTQ shit, it was hard to believe. You kept your head down, once upon a time. Children were seen and not heard. You stayed under the radar. Or you were likely to get your head handed to you. Didn’t matter who you were. It was equal opportunity repression, but we didn’t call it that and we didn’t think about it like that. It was living. You kept a low profile, and you were grateful, more or less to be invisible, so anybody that noticed you didn’t stomp on you. Low expectations. Little ego. You got by.

“Yo Knife,” a voice said as Jack swung himself into an empty row of hard green seats at the back.

“Yo Sleeze,” Jack said. He didn’t have to look toward the voice. Faces change but voices are forever.

“You on da bus,” Sleaze said. Sleaze was a tall Black man, a Liberian guy with a big voice and a bigger personality who took no prisoners inside. But then neither did Jack. Jack’s sheet included reckless driving, death resulting. It was what it was. No judge was ever going to give Jack his license back. And getting caught driving without was a one-way ticket back inside. It was what it was.

“You on de bus,” Jack said. Ask me no questions, I’ll tell you no lies. It was what it was. Sleaze had his own bags to carry. They nodded their heads. Their shoulders swayed back and forth at the waist. They walked the same walk. Solidarity forever.

“How long you out?” Sleaze said.

“Four months,” Jack said. “It’s a whole new world. You?”

“I got a year. But I am still a wild and free mutherfucker,” Sleaze said.

Jack dipped his head and gave Sleave the old hairy eyeball.

“Working at Stop and Shop,” Sleaze said. “You do what you got to do.”

“I hear that,” Jack said.

“ Whach-yoo up to?” Sleaze said.

“Feeling my way, man,” Jack said. “Just feeling my way.”

“Not likely. The Knife always got a little hustle,” Sleaze said.

“No hustle now,” Jack said. “After 43 inside, I ain’t got no hustle left.”

“Yes, you do,” Sleeze said. “I know you. Can’t keep a good man down.”

The bus passed City Hall, climbed Exchange Street, passed the Post Office and a bright orange night club across from where the LeRoy Theatre used to be. It jerked when it started after every light and hissed with each stop. It swung around the new train station where a thousand cars were parked but nobody was waiting for the bus, and came down Pine Street to Main Street, swung a right and chugged through a neighborhood that was full of old brick mills and pink or lime-green triple decker houses with porches on the second and third floor, clotheslines in the back yard and grape arbors next to the black asphalt driveways that took up most of their yards.

Then the bus crossed Route 95, where the overpass runs high over Pawtucket, just after 95 bends and before the land falls off into the river valley behind them. The sun was red and golden then, low on the horizon, glinting into their eyes, reflected off the cars on 95 below them, a river of jewels, the sunlight illuminating North Providence and Providence, itself, in the distance, so all you could see was the bounty of light, and not the carwashes and industrial buildings, the storage facilities and muffler shops and office buildings that had sprung up in the last forty-three years, all the buildings that Jack didn’t know any more but knew were there.

“We be losing that sun early now,” Sleaze said. “Dusk at 7. Sun gone by eight. Summer gone again soon as it comes.”

“Make hay while the sun shines,” Jack said. “Summer will be back again. Can’t say the same for you and me.”

“Speak for yourself, dude,” Sleaze said.

“I did,” Jack said. “And I will. Everybody dies of something. Sorry to be the bearer of bad news. So, get it while you can, brother.”

The bus drifted down a little hill. There used to be a neighborhood here, Jack thought. A couple of dive bars. A good diner. A little neighborhood storefront supermarket. A butcher. A barber. A hairdresser. A fish and chips place. Woodlawn, they called it Woodlawn. French-Canadian, back in the day. And Irish. They once had a little movie theater and a school and a big RC church up on the hill.

All that was gone now, Jack thought. The storefronts were empty. There were two little used car places, one on either side of the street where the little grocery store and its little parking lot used to be. The church was still there but it looked empty and forlorn. There was nobody walking on the street. Everybody is pretty much the same now, Jack thought. Nothing but chain fast food joints and a pawnbroker. The place and people were empty. We are all equal now, Jack thought. Equally empty.

When the bus stopped again near the Little Sisters of the Poor, four people got on, all women in jeans and pink smocks that suggested they worked at the nursing home. CNAs or dietary workers, Jack thought. Nurses drive their own cars.

Three of the women were in their fifties or sixties, women who were different tones of tan, brown and black, one with a brilliant red kerchief, another with glasses and springy gray tight curls, a third squat and strong. They spoke Spanish to one another.

The fourth woman, though, well she was definitely on. Perfect deep tan skin, deep, brown, almost black eyes, and dreadlocks that fell almost to her waist. It wasn’t clear how or why a woman like that would be on the #1 bus in the first place. Or any other bus, to tell the truth. She wasn’t no bus. She was a Vett or a Caddy, four or even five on the floor, 490 horses with that 6.8-liter V8 under the hood, adrenaline red finish buffed to shine, the chrome glistening in the late day sun.

–

It had been a day. When Bernadette Ward climbed up the steps of the #1 bus outside work, all she thought about was sitting down. On her feet all day filling scripts. People think medicine is magic, so they all use too much of it. There were patients in the home on eight, ten, sometimes eighteen different drugs.

But pharmacists know that all drugs are trouble. They’re all poisons, particularly if you use them incorrectly or layer one on top of the next. Still, somebody had to keep it all straight. Somebody had to check for allergies and for interactions and contraindications. There was kidney function and liver function to worry about. Adjusting doses as necessary. Negotiating biosimilars with doctors, who ordered drugs without thinking and then took forever to call Bernadette back, if they ever called her back at all.

The patients, their families, the CNAs and the nurses wanted every medication for every patient yesterday. But one tiny mistake, one tiny detail left unchecked, and some poor old person might die.

But the bus, well, that was Bernadette’s liberation. How smooth life was without a car. You park yourself on the bus and leave the driving to someone else. Electric buses now, so climate smart. One bus to Kennedy Plaza, then a second bus home. Providence was this great secret, a gem that Bernadette hoped no one ever discovered – funky neighborhoods, art and music, not everywhere but available, not as cheap to live as it used to be, but a whole lot cheaper than Boston — and pretty quiet. You could walk in Dexter Training Ground or near the river, and it was quiet enough in the morning and at night to get some writing done.

Sad though, that they were losing the early morning and late evening light.

But that time before and after work, that time was a gift. To see the early morning light filtering through the maple leaves. To sit in the park and listen to some kid with an electric guitar play the blues, or a little theater troop set up and do Hamlet or Fences, that was heaven on earth.

The ladies got on first. They sat on the benches behind the driver, and they chattered away. The benches were full but there were seats in the back. Two old men back there. I should be okay, Bernadette thought. I can sit and vegetate. Ten minutes, no more. I owe myself that.

–

“Hey sweetheart,” Jack said, when Bernadette came to the seats in the back. He slid over to make room for her on his seat. But she walked right by him and sat on the last seat in the bus. She slid over to the window, so she’d have a place to rest her head in case she started to fall asleep.

The bus lurched forward, the setting sun still red and golden when they saw it at the cross streets, low in the western sky, snuck between the triple-deckers and the old mills. Jack was old enough to remember when grey and black smoke poured out of the smokestacks of some of those mills, when the air was grimy, and a gray-brown haze settled over the city by mid-afternoon. The air over Providence and Pawtucket was clear now, most of the time. A thousand times better.

Jack caught Sleaze’s eye and nodded. This was cake. She had come to them. He knew how the game was played. He turned.

Bernadette was looking out the window, acting like she hadn’t seen him. Very foxy.

“Hey sweetheart,” he said. “You don’t know what you’re missing way back there. Come sit by me.”

There was a rumble as the bus accelerated. They were below the Met now, below where Hope Webbing and Rhode Island Candy used to be, driving on a piece of what used to be hillside, a zillion years ago, looking down on what used to be a little valley with a stream running through it, all of which was now replaced by Route 95 which was streaming with cars and trucks now, the red and golden light still reflecting off their roofs, windshields and headlights, a river of golden light for a moment, until the sun set, the drivers south all slowed to a crawl by the glare of the sun, the drivers north moving quicker on their way to Attleboro, Mansfield, Sharon, Canton, Quincy, Boston and points north.

“Hey babe, it’s me,” Jack said.

Sleaze, watching from his seat, shook his head. He don’t want to go there, Sleaze said to himself. He don’t.

Then Jack slid over to the aisle and stood up.

Bernadette stood up. You don’t have to think about it. You just have to do it. That’s how it is in America. Still. Always. Doesn’t matter who you are or what you are. You raise your head, they cut it off. You live your life, they want a piece. There was a Black man sitting back there as well. An old Black man. Didn’t matter. Doesn’t it ever stop.

“Who are you?” Bernadette said.

“Your dream come true,” Jack said,

“You aren’t getting my meaning. I meant who, just who do you think you are, talking to me like that?”

“Your dream come true, baby. Right here on this bus. Right now. There’s time,” Jack said.

“You have no right to talk to me like that,” Bernadette said. “To anyone like that. This is a public place. Have you no decency?”

The bus had passed LA Fitness and was below Gregg’s restaurant by then, the light of the setting sun illuminating the parking lots and store fronts and the hospital on the hill hovering over them to their left.

Jack paused, not sure for a moment who he was or where he was. His idea of freedom was always doing what he wanted when he wanted it. You get it while you can. He lived by his wits. And he never turned his back, not on anyone.

Bernadette grabbed at her shoulder bag with one hand and reached for the driver call pull-cord with the other.

But Jack was quicker than she was. He reached for her arm and had his hand on her hand before she reached the pull-cord.

But then he fell backward, into the aisle.

Sleaze had his arm around Jack’s chest and neck. He lifted Jack away from that last row of seats and dragged him down the aisle to the rear door of the bus.

“It’s my stop,” Sleaze said, as the bus passed the cemetery, the trees there blocking the light of the setting sun. “Our stop. Driver, we’re getting off here.”

The bus slowed and stopped just past the fire station, across the street from Kentucky Fried Chicken, across from Action Auto Parts. It hissed as it slumped to one side and the door opened to let passengers off. Sleaze dragged Jack to the steps and then pushed him down them, so they were standing together on the sidewalk as the doors of the bus closed and the bus pulled away.

“What the hell was that?” Sleaze said. “Didn’t you learn nothing from all them years inside?”

“I was just exercising my constitutional rights to free speech,” Jack said.

“The hell you were. You were exercising your constitutional rights to get your ass thrown right back to where you came from. That woman didn’t do nothing to you.”

“I wasn’t thinking none about that. I was thinking about what I could have done to her.”

“You crazy, man, just crazy,” Sleaze said. “That was my stop though. Stop and Shop is that way, just over the highway. Where you off to, man?”

–

The sun had disappeared. The late August sky lit up orange, purple, red and pink over west Providence and Johnston, the hills covered with houses the way a blanket covers a bed, the valleys pockmarked by old mills and office buildings, evidence of a people and a culture that has come and gone.

“Headed to Olneyville,” Jack said. “I can walk to Kennedy Plaza. It ain’t far. I’ll get the bus from there. Babysitting the grandkids.”

It was dusk now. Sleaze started walking down Branch Avenue towards Route 95. He took a few steps and then turned. Jack was still standing on the corner in front of the fire station.

“Getting dark early now. Damn, I miss that light,” Sleaze said. “Be careful, brother, Don’t want you run over by a truck.”

Sleaze turned and Jack turned in the dusk. They went their own ways, one to the south, the other to the west, walking as if in slow motion, each alone on streets where you could now barely see to walk but which a moment before still held light.

–

Many thanks to Catherine Procaccini for proofreading and Brianna Benjamin for all around help and support.

Please click here to receive Michael Fine’s monthly short stories and his new series, What’s Crazy in Health Care. Please invite others to join by sending them the link here.

Information about Michael’s books, stories, posts, talks and performances is available at www.MichaelFineMD.com or by clicking the link here. Join us!

Read more short stories by Michael Fine, go here: https://rinewstoday.com/dr-michael-fine/

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor in Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.

He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.

He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.

Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.