Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Rhode Island Weather for June 5, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 5, 2025

- RI Veterans: Did you know? 05.06.25 (Rental help, events, resources) – John A. Cianci June 5, 2025

- We Cook! Mill’s Tavern Rosemary-Lemon Statler Chicken, Yukon Golds, Haricot Vert and Dijon Demi June 5, 2025

- ICE arrests nearly 1,500 in Massachusetts. First part of “Operation Patriot” – Nantucket Current June 5, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 4, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 4, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

The Sad and Lonely Death of Katydid Desrosiers – (part one) – Michael Fine

By Michael Fine

Note to readers: This story is longer than most I’ve written, so we’re going to send out one section a week over the next six weeks, on Sundays. I’d suggest starting it on your cell, and if you like what you see, consider downloading it and printing it out — it’s a little long to read cramped over a tiny little screen. It’s available for printout on https://www.michaelfinemd.com/short-stories.

The influence of Leo Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Illich will be apparent to many readers, and is gratefully, and humbly, acknowledged.

Copyright © 2023 Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

Week 1

It wasn’t much of a car to begin with. It was a 1994 Saturn with 257,000 miles on it. It had bald tires and one of the doors was white, not dull green like the rest of the car. The car’s inspection sticker was three years lapsed, so Katy drove it only at night. She didn’t drive it very far.

She had her places. There was a section off Mineral Spring Avenue in Pawtucket, down a road you couldn’t see from Mineral Spring, near a junk yard that was way back in the middle of no place, a place nobody drove by at night. Then there was a place in the industrial park in Cranston, near the ACI. Katy knew to avoid Atwells Avenue near the port in Providence, which looked deserted at night but where all sorts of people gathered in groups of two and three to transact business, their business, of one sort or another.

But out Silver Lake Avenue in Providence, near that big city park with the Native American name nobody can pronounce, were a few good dark streets. Sometimes she used the parking lot of the Walmart in Cranston, back behind the building where the trucks came to unload, which was okay if you went into a far corner and inched out of the light, so it looked like your car was one of the associate’s cars. But there was too much light there anyway, which made it hard to sleep. The trucks came and went all night. They made lots of noise, bumping and clanging, which made it harder to sleep yet.

You could also try one of the back streets just off Lonsdale Avenue, the streets that dead end at Lincoln Woods and sit where Pawtucket, North Providence and Lincoln all come together, where the cops don’t come much because nobody can figure out which town is which. But you have to park near houses over there. Eventually some cop raps on your window with a flashlight and tells you to move on. Not many bushes over there. Not much privacy. It’s best if you move every day or every other day. That way nobody notices.

Katy thought of driving to Florida in the winter. Florida or Georgia, or even Mississippi, somewhere on the Gulf Coast. She had a sister who used to go to Panama City for two weeks every winter. But she didn’t know if the car would make it that far, and she didn’t know how she’d pay for gas.

No medicine now. There wasn’t money for medicine. No restaurants either. Katy drove from place to place at dawn or dusk and parked the car.

She walked all day long to try to stay warm. She had her libraries. They were warm in the winter. She knew the parks. If you walk in the parks nobody knows you are there. She thought. She left people alone. They left her alone. It was better now. The car had a radio she listened to at night so she’d know what was happening in the world.

Her job was to figure things out. All she had to do was think. There must be a purpose to all this human life, she thought. The reason we are all here. My job is to figure that out, and then I can come back and be with people again.

Vernon Jenkins first noticed the car the day after Thanksgiving, after the relatives had come and gone. He skipped breakfast, thinking to save an appetite for the leftovers, which filled the refrigerator in the kitchen, and the overflow fridge in the garage, after Jane she cleaned up from dinner, Vernon helped as much as Jane let him, which meant drying the dishes, washing the pots, and putting the fancy china away, back in boxes to go to the porch where it would sit for another month before it was used once more and then would be delivered back to the attic to sit gathering dust for another year.

It was an old green Saturn with a sagging suspension and one white door. The finish was dull. The car sat a little crooked on the street, like a cat with an inner ear problem that couldn’t hold its head straight. The back seat was jammed with clothing. There were books and magazines stuffed between the windshield and the dash. Vernon noticed the car when he went out to walk the dog just as the eastern horizon was red with that rosy fingered dawn, a twinge of hope after a cold night, when there was enough light to see by but before the chill was out of the air, before the sun, low on the horizon because it was December, glinted into his vision and made Vern squint.

He didn’t make much of the woman sitting in the driver’s seat. He couldn’t really see her face. She moved while he was watching. She reached up to scratch her face, her eyes closed, so he knew she was alive and he could relax and not think any more about her.

The car was gone by mid-morning. But it was back again a few days later, parked down the block. Different place, same car.

Curious, Vernon thought. Not really an issue though. Like a garbage can left on the street. You just note it, wish the person who owned it would roll it back inside, wonder if the people were away for a few days, and then don’t think any more about it.

No ideas but in things. That was what Katy used to believe. Ideas didn’t matter. People matter. Actions matter. All she could see, once upon a time, was how to get things done, back when she was a woman who let nothing stand in her way.

The world unfolds. She saw herself twelve, barely awake, in the middle school chorus room in Rutherford, New Jersey, the New York City skyline still visible through the windows as the sun was going down, boys playing basketball in the school yard, cars driving up and down Park Avenue in Rutherford to the traffic circle. She could also see those boys who would be in those cars in the summer five and six years later, circling, leering, looking too cool for words and she felt her heart beat hard when she saw them. And then a picture of a man in a red car with its top down in the summer, all these ideas and pictures coming together, mixing and then separating, as if her brain was constantly shuffling cards.

At twelve again, she saw herself sing when she was told to sing, quietly at first, because she didn’t want anyone to hear her, or look at her: she was still a girl in a boy’s thin and bony body, the daughter of a dentist and a school teacher now retired from that work, the third of five children, the quietest and least important of the five, happy to find a corner where she could hide and read a book, happiest if no one looked at her to see just how ordinary, just how plain she was, that she was just a little white girl, pale as paper and even more ordinary. She sang as she was commanded to sing, a soprano in the chorus, the same part everyone else was singing, quietly so as not to be heard, invisible as one of thirty or forty middle school students who all looked alike. She loved the feeling of that singing anyway. She loved to sing in secret, when no one could hear her. She felt her soul rise as she sang, however quietly.

That day, something was different. The other voices began to fall away. Then she was singing alone and people around her were listening. They were mouthing the words. They just let her sing. They were looking at her, wanting to hear her voice. Katy was ashamed, unclear why they were quiet though she was still singing. Even so her voice grew stronger.

–

The woman who came out of the studio in Cranston didn’t even see the car. It was cold and just after dark. She wore a heavy cloth coat with a faux fur collar and pearls, with white shoes that had red soles, beautiful shoes that she hated to wear as she walked across the parking lot, shoes she would take off as soon as she got to her own car, a large white SUV with a round insignia on its rear door, a door that opened electronically as she approached, as the car itself unlocked automatically as soon as that key fob was a few feet away.

There wasn’t time to do anything besides change out of those shoes. Then the woman was going to the gym. She’d shower at home, redo her makeup and change, and would put on another pair of shoes, less comfortable perhaps but more noticeable. Then there was an event at which there would be dinner, or at least, the hors d’oeuvres out of which a meal could be constructed, quickly, so she could devote her time at her table to listening to the people around her, so she could be seen and seen listening. She’d speak a little at a time, strategically, and no one would notice that she was barely eating, herself.

She owned a Saturn once. Her first car. Not much to look at. Inherited from her step-father in St. Louis, who died in a room alone in Las Vegas after her mother threw him out. She drove it to Providence for her internship when she was just starting out. You couldn’t kill that car. It ran and it ran and it ran. The suspension wore out early and you could feel every bump. She drove it all three times she worked in the district offices – first Greenville, then West Bay, then East Bay, forever hoping for a turn at the City Desk or the Washington Bureau, which never came before she jumped to television news, the paper crumbling under her feet after it was sold to that impossible conglomerate in Texas, the business model of newspapers have been decimated by Craigslist. By Craigslist, by God. The place where people looking for a one-night stand went, as the on-line world supplanted the real world, as it pushed aside all those years of wisdom that lived at the paper, all that smart street savvy, all those people and their stories and their focus on getting at the truth, truth oiled with Irish whiskey and lots of good stories. All that was history now. She never thought about it.

The Saturn was green like her car had been, the one she called ‘sweetheart’ and kept on running until she started to be on television, when she could afford a new car for the first time, until television itself was eviscerated. This one had one white door. Hard to believe that old car, her old sweetheart was still on the road. You never know. Rhode Island, one degree of separation. This one had bald tires and a sagging suspension, but that happens to cars over time, even quicker than it happens to humans, to women. Perhaps someone had come through a stop sign and smacked into the passenger side door, shoving it in, and perhaps they replaced it with a white door from a junkyard. Silly to think this was the same car. It was parked on the street, across from the office parking lot, after everyone else went home. Non-descript. Maybe there was someone sitting in it. The engine was off. Maybe a person in the front seat with the flashlight from her phone on, looking at what, a map? People don’t use maps anymore. A magazine? A book? When was the last time the woman herself had read a book. Emojis, maybe, as she ran from place to place. Twitter, absolutely. Instagram. And TikTok, the tools of the trade.

She drove past. And picked out her ensemble for the evening in her mind as she drove by.

___

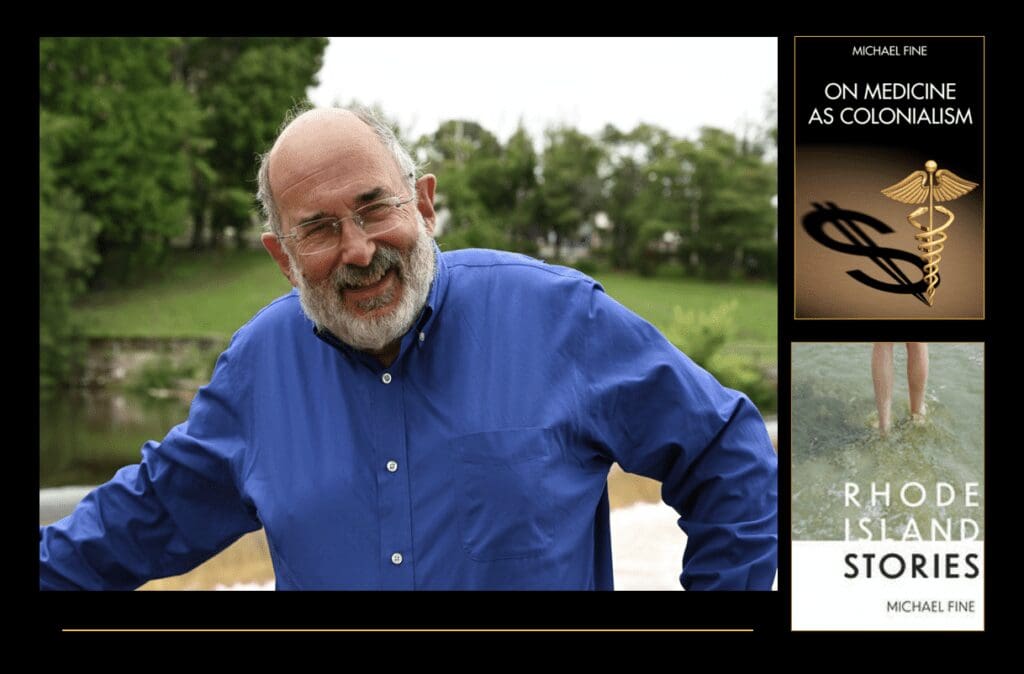

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor in Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.

He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.

He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.

Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.