Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Out and About in RI: Former Pawtucket Mayor Henry Kinch Tribute in Photos June 24, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather Forecast for January 24, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 24, 2025

- ART! Mark Freedman, first featured artist of Summer Art Shows at Charlestown Gallery June 24, 2025

- The Bellevue Hotel: Procaccianti Co. New Luxury Boutique Hotel Set for Newport’s Iconic Bellevue Ave June 24, 2025

- Mike Stenhouse, CEO of RI Center for Freedom & Prosperity, named into College Baseball Hall of Fame June 24, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

The Promised Land: a short story by Michael Fine

© 2024 by Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

The Promised Land. Somewhere Over The Rainbow. Don’t wait for your pie in the sweet bye and bye, Have it now with ice cream and a cherry on top. “In that day the Lord made a covenant with Abram, saying “unto thy seed have I given this land, from the river of Egypt unto the great river, the river Euphrates: the Kenite, and the Kenizzite, and the Kadmonite, and the Hittite, and the Perizzite, and the Raphaim, and the Amorite, and the Canaanite, and the Girgashite, and the Jebusite.”

What is all that promised land stuff about? Denise wondered, as she parked her car and walked through the parking lot into Medium. Why have a promised land at all? Who gets to make such a promise, and why should anyone care? Isn’t all property theft? And isn’t ownership and control both illusionary and the source of much of the world’s warfare and struggle?

Abram was a man who spoke to God and had visions, she thought, who left his home in Ur of the Chaldeans because of this God told him to do so, who walked a thousand miles after getting that instruction, and who thought his descendants had been given a block of territory the size of an empire and the right of dominion over all the tribes and people who had lived there for generations, a promise or a fantasy, depending on your perspective, that would doom those descendants, one of whom was Denise herself, to millennia of warfare and then exile. Pursuing that fantasy, building kingdoms and temples and so forth, and then picking fights with empires much bigger and stronger than we were, doomed us to destruction and then to roam over the known world like wind-driven leaves, stateless and weak for two thousand years, murdered and reviled.

As of today, she thought, 32070 Palestinians and about 1450 Israelis and other people have died in Gaza, and about 130 people are still considered hostages, although many of those are likely dead, the result of all this human intransience and hallucination. Is the promise in the promised land real? What value is it, and to whom?

The fence door behind her rolled closed and then clanged shut. Then the door in front of her rolled open, the motor whirring like a washing machine.

Denise walked into Medium. Medium Security, the largest ACI building, where most prisoners live. Or try to. She walked to the security desk where they took her wallet and cellphone and gave her a badge. Another motor clicked on and whirred, one that sounded like an elevator. A big steel door opened, and she walked into a hall, the steel door slamming shut behind her again. The she walked through another door, out into the yard.

There were men in orange uniforms and blue overcoats with hoodies milling about the yard.

It was March. There was a cold wind from the west, a bitter, insistent wind. The sun was brighter than it had been but still lay low in the sky, bright sun that made Denise squint. She smelled sewage in the air, blowing over from the treatment plant near Route 95. Lots of concrete underfoot. Patches of dirt and gravel. Grass tried to grow in places, but mostly failed. A few weeds managed to grow near the ground, green even after the almost snowless winter, the only indication of life there, inside, a scruffy hint that life persists and is incessant. You try not to think about the men and women we put in cages. You try to forget that some men and some women live inside for years, their lives constricted, like the water in a washing machine which sloshes round and round and gets gray with soap and soil, water that is different in every way from the water that falls as rain or the water in streams flowing off a mountain or the water that rages in the sea. You don’t think about much when you go inside every day. Just the job you are paid to do. You think about the men and the women, the offenders, the inmates only a little: you think only a little about what they tell themselves to survive this, and never about what counts as hope and meaning for them.

Medium is not like Minimum, Denise thought, where most of the men will be out in a few months. Or Women’s, which is smaller and more complicated. Medium is where men with twenty-or-thirty to serve or life live, men who will live for years and years inside, and many will likely die here. What do they imagine when they walk outside and see the grass and the weeds growing in the cracks? Or see the sky? Or hear the trucks, just a mile away on Route 95? Or think about the shopping plazas, just a mile away in another direction? These men, who are out of sight, out of mind. Who live among us but are absent from us. Who we block out. Who we have discarded. Who are hidden in plain sight and not seen. Who are mostly Black and Latino, in this corner of New England that is overwhelmingly White, watched over by armed men who themselves are overwhelmingly White. What do we understand about these men? the offenders, the inmates, who are always hustling each other and the guards, looking for a little leverage, a little angle that might change their lives in some tiny way, remembering that they have nothing else to do and almost nothing to lose, now. So they are like the grass and the weeds that are growing in the cracks, imprisoned but unable to stop hustling, stop living. Because we are hardwired to live. To hustle. And to hope. Despite other human beings and what we do to one another. Despite all that evidence to the contrary.

Not A Block this time. Not where the clinic is. C Block. Which is all concrete and stainless steel, with a big open space for the offenders to mill around in when they aren’t locked down. That’s where the dogs are, the canines, the dogs we let offenders gentle and train. On their way to being therapy dogs or even seeing eye dogs if they are particularly good. Though it isn’t clear who trains who. The dogs calm the men down. They give the men focus and a relationship that matters. The men school the dogs, sure. But the dogs give the men way more than the men give the dogs, training aside, and perhaps more than any human being ever gave some of these men, by which I mean unconditional love, Denise thought. What the world need now. Is love, just love. Which doesn’t exist, inside, other than from dogs.

We don’t give the men and women inside, the offenders, not in any way, shape or form. We give them direction. Structure. Clarity. Zero tolerance. Actions have consequences. You better learn to comfort yourself, because no one is ever going to comfort you. But if we cut them any slack, if we ever give an inch, if we turn our backs for one instant, they will be all over our weakness, and will take whatever they can get, and it will be done and gone, or you will be, before you know what hit you.

The people in Rehabilitation Services, the teachers and the counselors and even the discharge planners are not really supposed to go to the cell blocks. The offenders are supposed to come to them.

But Archie was a special case.

Denise went to see Archie because Archie wasn’t going to come to see her. Archie was forty-eight going on eighty. He was a young guy, but you’d never know it because he looked so old. Decrepit. Done. Stuck in that wheelchair, both legs amputated below the knees, his puffy flesh flaccid and yellow, hanging in jowls off his face. Thick bags under his eyes. Eyes that were always red and runny. Thinning gray-white hair, just strands swept back over a tan and yellow scalp that was pockmarked by raised brown and red warty- looking patches, the hair swept back as if to disguise a head that was mostly bald, so Archie looked like an ancient hipster who didn’t understand that he was now old but wanted to cover his actually bald head with long gray stands of thinning hair. Which didn’t cover anything. Archie was worn out by the elements, by living. Beaten up and down by life. Not old in years. Just exhausted.

Archie was in on a conspiracy-to-traffic-minors-across-state-lines rap, thirty year sentence, twenty-two to serve, for hustling young Cape Verdean and Dominican girls he found walking home from Tolman High school in Pawtucket. He gave them hot shoes and hot looking bags, jewelry, a little rum and a lot of cocaine, and took them clubbing in exchange for passing them around, first to his buddies from Federal Hill and then to the smart money, the wise guys from Cranston and Johnston and Federal Hill, the card sharks and the used car dealers and once in a while to the college boys who came down from College Hill and Barrington because they didn’t know what was good for them but thought they wanted to experience life as it is, life in the fast lane, to see what they could learn about life on Allens Avenue, where life got started about 11 pm and went on until dawn. The trafficking charge was a trumped-up charge. Archie was probably guilty of it, of course, but the evidence that convicted him was as thin as a cigarette paper. Just the testimony of a snitch from Allens Avenue who the cops paid off, those girls having long disappeared into places like Boston, New York, Washington, Atlanta, and Miami, long before any trial. Trumped-up, but the best the cops and the prosecutors could do. They wanted Archie off the street because he was a mean son of a bitch who was moving from Cape Verdean and Dominican girls to the hot Irish and Italian girls from the Hill and Fairlawn, and was moving beyond those girls, hustling thirteen year old boys who didn’t know who or what they were, who came from the East Side, Barrington, and East Greenwich, who would come to Thayer Street to shop and hang out, because they had no idea that there were places like Allens Avenue yet. Their parents dropped them off at the Mall and then they’d drift over to Thayer, the parents never imagining that there were snakes and alligators like Archie, slithering about in the swamp, submerged among the rotting trunks and the weeds. One or two of those kids ended up dead in the river, decomposed, and no one could finger the killers, but everybody knew what everybody knew, and decided that the world would be a safer and better place with Archie in jail, thus the trumped-up conspiracy rap, which kept Archie quiet for twenty-two years, a period when those bodies stopped showing up in the river from time to time.

Archie was hanging out right outside C Block, smoking. Sitting in the chair and smoking. Those butts and sugar diabetes had cost him his legs but that didn’t slow him down any. The chair slowed him down some. Which was probably a good thing. Whether or not he was rehabilitated was an open question, but it would be hard to make the kind of trouble he had once made now, Archie being old and completely unattractive to anyone, and the lack of legs restraining his behaviors. Perhaps.

He didn’t look at Denise when she came next to the chair. He just looked out into the yard, smoking.

“Whach you doin’?” Archie said, his voice deep, raspy and gravelly at the same time. It came from his throat because he didn’t have much puff left, but there was still a growl in it.

Denise crouched next to the chair so she was at eye level.

“You ready?” she said.

“Ready for what?” Archie said, growling. He kept looking into the yard, blinking his eyes from time to time, his skin wrinkled and pasty, so he looked something like an alligator after all, an alligator laying in the reeds waiting for prey.

“Ready to be out of here. Two weeks. Got a plan?” Denise said.

“I’m always ready, baby. You know that,” Archie said.

“I know what I see. And what I see is an offender who hasn’t been on the street in twenty-two years, who has no idea about what’s out there,” Denise said.

“What’s out there is life. What’s out there is breath. What’s out there, is, well, what I want and need is out there. You don’t want or need those particulars,” Archie said, and he turned his eyes to Denise for the first time and looked her up and down the way some men once looked up and down some women, undressing them with their eyes, a way that people don’t look at one another much now, because everybody knows to look at another person like that is so demeaning.

Denise, of course, was used to this kind of hustle, and didn’t give one inch. You give them an inch, they’ll take a yard. Or a mile. Or a whole country. She stared back, stared right through Archie, looking through him as if he were a stain on an old shirt or an insect.

“You got a plan yet?”

“Who needs a plan? I hit the street and find who I need to find. Then I plan.”

“Exactly what I’m worried about. You hit the street and find who you need to find and you’ll start doing what you shouldn’t ought to ever do again. And end up right back here for a another thirty, twenty-two to serve. Or dead.”

“I ain’t never coming back here,” Archie said.

“You don’t know that. Two thirds of the men who leave here are back in six months. They all said that.”

“I’m the other third.”

“In your dreams. I can get you in at a halfway house for thirty days. That way you don’t freeze to death on the street.”

“Not happening. I got friends. I know a guy”

“Which is exactly what I’m worried about.”

“My problem, not yours. People owe me. Promises were made. “

“I can’t let you just walk out of here with no plan.” Denise said.

“You can’t not let me. You got no say in this matter. Two weeks from today, I walk out the front door. A free man. Roll out. I roll out now.”

“I can get you five days of your meds. I’ll make you an appointment at a clinic where they take care of released offenders. But you need a place to stay, and you need to see a doctor so you can get meds on the outside.”

“Have those meds waiting for me at 2 pm a week from Tuesday. I’ll make out. You’ll see.”

“I’ll do my part. You do yours,” Denise said, and she stood up as Archie stamped out the cigarette he was smoking on a metal part of the wheelchair and threw the butt onto the ground. Then he pulled out another cigarette paper and a used envelope full of home-roll tobacco, and rolled himself another.

Connections, Denise thought. He clearly has connections and a little pull. I wonder how that works. Doesn’t matter. He’ll be dead in a week. They are all like that. They think they know what’s what. Then they hit the street. They score before a week is out. But being wiseguys, they shoot their old dose. They forget their tolerance is gone. About fentanyl and all the other crap that’s now on the street. They think the junk on the street is the same junk they were shooting back when. A generation or two ago. Sometimes just a year or two ago. A needle in a vein. And then boom. Or whoosh. Their breathing stops, and that’s how we find them, dead on a toilet seat. At a kitchen table. Slumped over next to the bed they were sitting on. In a car. In an alley. Dead. Cold. Blue. The needle still in their arms.

Denise had seen it a thousand times if she had seen it once. The promised land. A score. A taste. And then gone. The wiseguys know the truth, they think. They all think they are better than that. Smarter. On their game. Until it’s too late. And they drop and turn blue and get cold like every other wiseguy before them. So they never learn. Nor do we.

The thing about Allens Avenue is that it isn’t very far from Edgewood, maybe a mile and a half, maybe two miles. You pass the Sea-plane Diner and the place that Russian Sub used to be, before it sank in a storm, Rhode Island being Rhode Island, where you can’t make this stuff up. Then you pass the piles of metal scrap and the cargo ships parked at the pier, waiting to be loaded. The cranes that scrunch the scrap as they lift it in bucketloads. The gas tanks. The railroad tracks. The road climbs a little hill, passes a restaurant or two and some buildings. Past the What Cheer Tavern. A fishmonger and a meat market. Then down the hill again, past Johnson and Wales, and then you’re there. A quiet neighborhood of old colonial houses on small lots and triple-deckers. Looking out on the bay. So close you can see the sailboats in the bay, the wind off the bay making the trees bend and the flags and banners flap, the seagulls floating on the breezes, cawing, calling out to one another, the smell of seaweed and diesel oil rich and thick and part of the experience of being there and being alive, but that part of Edgewood so close to the water that you sometimes have to evacuate, when a hurricane blows in late summer and the storm-surge and giant waves wash up, all the way up, onto Narragansett Boulevard itself, which is what Allens Avenue becomes, the same street but with a different name, as it rises out of the port and enters holy Cranston.

Denise drove up Allen’s Avenue to Brown a few days after Archie’s release. It had been raining for days, a dark, cold rain that seemed endless. Water flowed in sheets over the sidewalks and roadways. All the low places had puddles the size of small lakes, that turned into little seas with waves when you drove through them.

It had been days since Denise had seen the sun. The wars in Gaza and Ukraine wore on and seemed never-ending, the cruelties on all sides unimaginable. October 7th. The recent history of the Jewish people recreated with unbearable barbarity, the traumas that we know about and acknowledge but those we also bury to live our lives, suddenly present again and now unescapable, as Israelis acknowledge that they are also Jews, finding sudden solidarity in tragedy, murder and mayhem once again, recreating a past we can’t escape because we keep recreating it, our endless fascination and identification with the aggressor, as we turn ourselves into them, a reaction formation if ever there was one. Thenn the Israeli response. Gaza flattened, like Dresden, Aleppo, or Mariupol. The civilian casualties, the displacement, endless hunger and fear, the people whose eyes look like the eyes of concentration camp survivors. Do it to them before they do it to us. Reaction formation. My people, Denise thought, my beautiful, haunted, arrogant, yearning, intransient people, who never learn from our history, who think God speaks only to us, and then are quick to ignore what we think we hear. Or heard. Like everyone else. Who fight desperately for our freedom and can’t ever govern ourselves. Who love our children and preach loving kindness, justice, and repentance but then are too often hardhearted, immoral, lewd, violent, and self-serving. Just like everyone else. We say we want justice and peace. And then we lie, steal, cheat, bomb, starve, and subjugate.

Where was the humanitarian aid? Why has Israel not built tent cities for civilians and new field hospitals to replace those Hamas had occupied and subverted? Hamas knew what Israel would do. They are no better, putting their own people in harm’s way like that. Wasn’t Israel just falling into a well laid trap, with the lives of tens of thousands the bait? The dancer and the dance. The hunter and the hunted. One no better than the next.

Denise thought for a moment about Archie and how he was probably out in the rain, in his wheelchair, some place on Allens Avenue, drenched, rolling up and down the street and looking for his people. One unsolvable problem after the next. Who are we that we leave ex-offenders to just disappear into the night, let them roll away into the sunset after they’ve paid their debt, after they’ve flattened their bid? How is it that we don’t provide food and shelter and a warm place to stay, the so-called three hots and a cot, to everyone, so no one ever has to live on the street in these United States? Where is the president, the governor, Congress, the Legislature? How can we allow people to live on the street, to go from prison to the street or the hospital to the street? And live, like packed animals, in shelters that put people back on the street every morning at 6 or 7 AM? And yet it happens all the time. We turn our eyes away, as we harden our hearts. Denise’s mind flitted back to Gaza: Where was the so-called world community? Where were the decent people of other nations, who should pull the combatants apart? Does the rule of law, of civilization itself have any meaning? Why had everyone let the situation in Gaza and the West Bank fester for so long? What exactly was this idea of a promised land good for?

You drive without thinking when you drive a route you’ve driven a hundred times before.

A conference. The car radio droned. Denise steeled herself for that, for a day of boredom, sitting still and listening to the speakers drone on and on, their PowerPoints undistinguishable, one from the next. Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity. Structural racism. Substance use disorder. Autonomy, beneficence, non-malfeasance, and justice. Harm reduction. Self-monitoring. Problem solving. Consequences of choices. Moral injury. Social proof. All these bright ideas on the screen one after another, in a warm well-lit room as people drank coffee and ate donuts, while three thousand people are locked up just three or four miles away, while all sorts of badness is going down on the street maybe two miles away, and while bombs are falling in Gaza and in Ukraine.

You steel yourself so you don’t see ugliness. So you don’t see piles of scrap. So you don’t see tank farms and cranes. So you don’t feel the jolt as you drive over the railroad tracks.

Suddenly a garbage truck backed out of a parking lot into the street, its backup lights flashing and the automated beeping noises loud and instant, BEEP BEEP BEEP. And Denise had to stop. Short. No choice but to jam on the brakes.

Then four men stepped out from an alley behind Denise’s car.

They surrounded Denise’s car, one next to each door.

They were men of different sizes and colors and all were wet. They wore wet down parkas or hoodies, wet watch caps and face masks, as if Covid was still on. They carried box cutters. The man at Denise’s window knocked on that window and gestured to her to roll the window down.

This isn’t happening, Denise thought. This is Providence, not Tijuana or El Salvador.

She threw her car into reverse and hit the accelerator. And then was thrown forward in her seat, as her car hit something big. Her hand went up, a reflex, and prevented her head from hitting the steering wheel. That’s going to hurt like hell tomorrow she thought, as she looked into the rear-view mirror, saw the old yellow bulldozer that had appeared behind her car, and felt her car rock as the goofball next to her pulled on the doorhandle of her door hard enough to break it off.

This isn’t happening, Denise thought. The door is locked. They can make trouble but they can’t get at me. Not unless I crumble and open the window or a door. Not unless they take a wrecking bar to my windshield.

She leaned on her horn. The blast of the car’s horn filled the air and hurt, as only an incredibly loud noise close up can hurt. I’ll stay where I am. I’ll keep my wits about me. I’ll sit here until help arrives. She dialed 911.

Then the car rocked again and crunched, the glass behind her shattering. One of the wiseguys had a wrecking bar in fact and was smashing the rear windshield with it. Denise covered her head with her hands, afraid of flying glass. She dropped her phone as an operator came on.

Holy shit, Denise thought. Holy shit.

“911,” the operator said from the floor. ”Police, fire or medical,”

“Medical,” Denise said. It was just a reflex. “No, police! Police now! I’m being carjacked!” Denise shouted, as the 911 operator began her litany of questions which Denise couldn’t hear because the horn was blaring.

Then everything fell silent except for the horn.

Denise looked up. And around.

The men were gone. Her rear window was bashed in.

The men had disappeared.

She came off the horn. And picked up her cell phone.

And then suddenly, there he was. Archie, in the flesh. In his chair. But with a great big orange umbrella over him, rolling down the sidewalk, or swerving from time to time into the street. Wearing a bright orange slicker that matched the umbrella. Project Hope, the umbrella said. Like he had become a street worker or something, doing outreach to the addicted, the strung out, and the lost.

Denise opened her window as Archie rolled up, next to her car.

“You’re still alive.” Denise said.

“Seem to be,” Archie said. “More than I can say for you, almost.”

“Were you behind this or in front of it?” Denise said.

“A little of each,” Archie said. “Like always,”

“You fucked up my car,” Denise said.

“They fucked up your car,” Archie said. “I was nowhere to be seen. Cars get fixed.”

“You know it was me?” Denise said.

“They don’t know nothin’. They just do what they do. Need what they need. Take what they want. You know the drill.”

“You stop them?” Denise said.

“Not exactly. Let’s just say they stopped. You leaned on the horn. Fought back.“

Suddenly there were sirens a few blocks away.

“Probably called 911. Atypical response. Most people just shut down, crumble into a little ball, and then the boys liberate what they need to for themselves. And disappear before anyone knows what hit them.”

“And you?” Denise said.

“Let’s just say I was in the right place at the right time. Or the wrong place at the wrong time. Whatever,” Archie said.

“So you’re okay?”

“You crazy, woman? You just had your car seriously fucked up and could have been murdered, raped, and left for dead on the street as they made off with your car. And you’re asking me if I’m okay? I’m okay. I ain’t dead yet, if that’s what you are asking. I got a roof over my head, three squares a day, more or less, and people. What else does a body need?”

“You chased them off, didn’t you?” Denise said.

“You don’t know that. And neither do I.” Archie said.

And then he was gone.

Three cruisers arrived pretty much at once — one coming south down Eddy Street, one swinging around the corner of Public and Allens, steaming down the hill from Broad, and one charging up Allens and the Cranston border from the south, all sirens blaring, all their lights lit up, washing the street in red, white and blue light of incredible intensity, making colored shadows and weird brightness that reflected off the rain slicked streets and off the raindrops and mist itself, weird light in a day that had been only dull.

The first one rolled up next to Denise’s car as the second one skidded to a halt in front of her car so she couldn’t pull away, and a cop jumped out of each one at the same time, their guns drawn.

“Carjacking?” said the first cop, a beefy looking guy with a red face, wearing a tactical helmet that was camouflage green, and a bullet proof vest. The second cop, a Latino guy with a mustache and long sideburns, had the same gear.

“I was mistaken,” Denise said, and the cops started to lower their guns, the looks on their faces a mix of smirks, relief and disappointment, looks that said, these women, they’re all like this.

“But I think someone threw something from that building there. Hit the rear windshield. Messed up my car bad. You can’t believe the sound it made when it hit my car. It sounded like the car had been hit by an RPG. Or by a wrecking bar. Now there is glass all over.”

“Okay,” said the first cop, raising his gun again, just a little, slowly, like he was thinking that maybe there was something to think about here after all. But what did some suburban lady know about RPGs?

“Open the car door and get out of the car, veeerryyy slooooowly, keeping your hands where I can see them. Hold your hands up as you stand.”

Which Denise did.

“I need a full statement. We’ll file a report,” the second cop said.

“Thanks,” Denise said. “Need that for insurance. Man, I’m glad you guys are here. That you responded and responded so quick. Makes me feel safer.”

“Don’t worry about it,” the first cop said. “Just don’t let anything like this happen again.”

You don’t know the half of it, Denise thought. But I ain’t going there with you. We are alive.

We are well, Denise thought. Those of us who are here and whose lives haven’t been destroyed yet are doing the best we can, loving who we can love and standing up every day. Spring is coming. Here in the promised land.

___

Many thanks to Carol Levitt for proofreading and to Brianna Benjamin for all-around help and support.

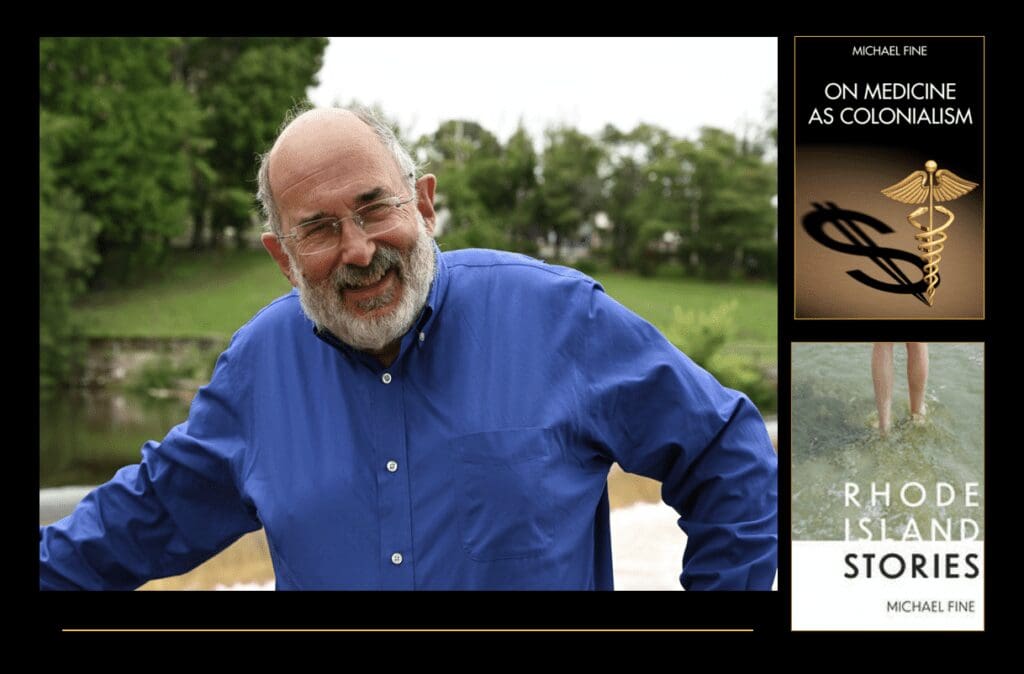

Please click here to receive Michael Fine’s monthly short stories and his new series, What’s Crazy in Health Care. Please invite others to join by sending them the link here.

Information about Michael’s books, stories, posts, talks and performances is available at www.MichaelFineMD.com or by clicking the link here. Join us!

___

Read more short stories by Michael Fine, go here: https://rinewstoday.com/dr-michael-fine/

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor in Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.