Search Posts

Recent Posts

- RI Veterans: Did you know? 12.06.25 (Memorial Day, Vets Cemetery, Events, Resources) – John A. Cianci June 12, 2025

- We Cook! Mill’s Tavern’s Mediterranean Seared Salmon, Olive Tapenade, Artichoke Hearts, Roasted Red Pepper Tahini June 12, 2025

- Why more Rhode Islanders are choosing Heat Pumps over traditional AC this summer June 12, 2025

- CNAs to be trained at URI in administering medication in state facilities June 12, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 12, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 12, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

The Power of Lived Experience: Why peer support is essential for recovery – Ocean State Stories

This story is published in partnership between RINewsToday.com and Ocean State Stories, a journalism initiative at Salve Regina University.

‘We want people to know that they don’t have to be alone in their mental health challenges.’

Jeremiah Rainville, manager of peer programs at NAMI Rhode Island, the local chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, has a string of credentials after his name. Among other accomplishments, he is a certified community health worker (CCHW) and a certified peer recovery specialist (CPRS). But his most valuable expertise may be his own ability to overcome early adversity and mental health challenges.

Rainville’s story is daunting. At age 2, he was placed in foster care after his mother developed schizophrenia. Over the next few years, a series of foster placements followed, most of them in abusive homes. He subsequently lived at St. Aloysius Home for Children, an orphanage in North Providence, until it closed following allegations of staff abuse. After being transferred to St. Mary’s Home for Children in North Providence, Rainville was adopted at age 9. Then he developed mental illness. Hospitalized twice at Bradley Hospital, he suffered more trauma when his adoptive father died and his birth mother killed herself. He was hospitalized several more times when he reached adulthood, including once for a suicide attempt.

Incredibly, Rainville not only learned to manage his depression and post-traumatic stress disorder but has also devoted his life to helping others in similar situations.

A turning point came when he became involved in Harbor House, a clubhouse (which has since closed) run by Fellowship Health Resources. The clubhouse model offers an empowering, peer-supported environment to enable people with mental illness to learn new skills so they can prepare to enter the community and find meaningful employment.

“I thrived in that community,” Rainville says. “With peer support, you can focus on getting well, using tools that peers share. We use our lived experience to connect with one another. You can’t get that in a clinical setting.”

Another step forward came in 2011, when NAMI RI offered him a transitional employment position. Rainville initially worked a few hours a week. Twelve years later, he works full time as a manager. He now leads the Peer-to-Peer Education Course, a free eight-week course open to anyone who has a mental health condition and wants to learn how to manage their recovery. The course, taught by people who are in recovery from their own mental health challenges, is offered five times a year. The class covers symptoms of mental health conditions, treatment options, and techniques that aid recovery. After they graduate, participants often join one of the many NAMI RI Connection support groups, which are facilitated by trained individuals who have learned to manage their own mental health conditions.

“We want people to know that they don’t have to be alone in their mental health challenges,” Rainville says.

Almost one in four adults in the United States experiences a mental illness, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s most recent national survey. Beth Lamarre, executive director of NAMI RI, says the organization recognizes how valuable peer support is for recovery. “People who have benefited from peer support as part of their recovery talk about how peers they interacted with knew about resources or different coping techniques that no one else would have known, because they have walked in their same shoes.”

When it comes to mental health, “nothing works on its own,” says Lamarre. “Clinical treatment alone is not always effective. Medication alone is not always effective. Peer support alone is not always effective. But having all those elements together creates a really strong foundation for people to move into mental health recovery.”

In recognition of his advocacy and accomplishments, Rainville is the recipient of the NAMI Inspiration Award, the Eleanor Slater Hospital Award, and the NAMI Ken Steele Award. He is also a member of the NAMI Board of Directors, where he represents the NAMI Peer Leadership Council.

But what he most values are the relationships with peers he has formed along the way. “I have a community I consider family,” Rainville says. “I can turn to them for mental health support when I need it.”

Peer support is also essential for recovery from substance use disorders. Almost one in six Americans ages 12 and older has a substance use disorder, according to SAMHSA. Opioid use disorders are currently the most critical challenge nationwide. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly three in four drug overdose deaths in 2020 involved an opioid. In Rhode Island, the Governor’s Overdose Task Force reported that 434 people in the state died of overdoses in 2022, most of them from opioid use. Such deaths increased significantly during the pandemic.

Dr. Josiah (“Jody”) Rich, an infectious disease and addiction specialist at The Miriam Hospital, helped develop the task force’s four-point strategic plan to fight the epidemic, which included guidance on treatment, overdose rescue, prevention, and recovery. Increasing access to peer recovery services was a core component of the plan to promote recovery, Rich says—and for good reason.

“Recovery is complex,” Rich says. “It’s not a box to check off. It’s a dynamic process that people continually work on.” Medication-assisted treatment is important, Rich said, but it’s not enough on its own. “Peers can connect to someone in recovery in a way that I can’t as a doctor,” he says. “I tell people who are recovering, you have graduated from higher education in survival of this disease. You have been through experiences and found a way to survive. That is valuable expertise that can be used to help people.”

Rich, who is also co-founder and senior medical advisor at the Center for Health and Justice Transformation—an organization working on the decriminalization of substance use disorders—says peer support is especially important for people who have been incarcerated and are trying to recover. “Traditionally our approach to battling drug use has been through the criminal justice system,” he says. “There is so much stigma and blame.”

That’s why peer support is essential. In a recent paper published in the Journal of Addiction Medicine, Rich and colleagues found that support networks that included peer recovery specialists helped people continue with medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder after incarceration. Peer recovery specialists helped people make medical appointments, find jobs, and avoid triggers that might lead to relapse.

Consensus has shifted over time about how best to treat substance use disorders, says Linda Hurley, president and CEO of CODAC Behavioral Healthcare, the state’s oldest and largest nonprofit, outpatient provider of treatment for opioid use disorder. Up until the 1990s, most of the assistance people received was from other people in recovery. With the arrival of managed care, insurance companies would only reimburse services by providers with academic credentials. More recently, consensus has shifted that a balance between these two approaches is needed.

[Read Ocean State Story’s Q&A with Linda Hurley.]

“I know this is an over-used word, but in a true sense we need an individualized, holistic approach for every single person who wants to recover,” Hurley says. “We need doctors, nurses, and behavioral health specialists who understand that substance use disorders are diseases of the brain, and can help people who come to us for care. At the same time, we know that individuals really do need the support of someone with lived experience. That is critical. It’s the glue that helps make connections.”

CODAC offers a number of peer support services in many of its treatment programs and through collaborations with other organizations. For example, CODAC’s peer recovery support specialists work with incarcerated individuals and in a mobile unit that treats people in underserved areas. CODAC is collaborating with Project Weber/RENEW, a peer-led organization that offers recovery support and harm reduction services such as a free needle exchange, fentanyl test strips, and medication to reverse opioid overdoses, among other services.

CODAC is also partnering with the Hope Initiative, a state-wide collaboration between law enforcement and peer specialists. An electronic system alerts the team whenever an EMT responds to an overdose call. A peer recovery specialist from CODAC accompanies a police officer to meet with the individual and encourage them to seek treatment. (Friends and family can also contact the Hope Initiative to refer a loved one to the service.)

“What’s important about the program is that we don’t just leave if someone doesn’t want help during a crisis,” Hurley says. “We talk to the family and provide information about how to access services. And we let the individual know that we will contact them two more times, when they’re feeling better, to see if they have decided they want help.”

“Peer support is amazing,” says Jonathan Sullivan, CPRS, CCHW, who is director of the Hope Recovery Community Centers of Newport County. Research has shown that peer support helps people remain in treatment for substance use, reduces relapses and re-hospitalizations, and increases satisfaction with the overall treatment experience.

“We are people who can meet other people where they are because we’ve been there,” says Sullivan, who recently celebrated 12 years of uninterrupted recovery from alcohol and drugs.

The Parent Support Network of RI operates the two Hope Recovery centers Sullivan manages, one in downtown Newport and the other in Middletown, as well as a recovery center in Westerly and a community center in Scituate. “We are all certified peer recovery specialists,” Sullivan says of the staff. “We are all people with lived experience, whether it’s with substance abuse, or mental health issues, or having family members with those challenges.”

The centers provide individual peer recovery services in person or by phone. This includes helping people fill out applications for supplemental security income or food stamps, assistance in finding a lawyer, or transportation to medical appointments. The centers also host a number of peer-led mutual aid groups, including Alcoholics Anonymous, SMART Recovery, and an LGBQT+ support group. Other mutual aid groups focus on reflective journaling, inspirational intentions, and nurturing resilience. “A lot of people have had experience with 12-step programs, and they haven’t done so well on them,” Sullivan says. “We try to provide people with alternatives. There are a number of ways to be in recovery.”

And there’s a reason they’re called mutual aid groups. “When something is peer led, it’s a mutual relationship,” Sullivan says. “We don’t sit with people and say, this is what you should do. We try to help people find their strengths, and then support them in what they want to do.”

The Parent Support Network of RI also employs dual-certified peer recovery specialists/community health workers in its Hope Recovery CORE Team, a statewide mobile outreach team that serves people who are homeless. The CORE Team provides basic needs assistance, such as food, tents, and cleaning supplies. It also offers harm reduction tools and referrals for treatment, recovery, and housing.

“We work a lot with the CORE Team,” Sullivan says. “If we have someone who comes to the Hope Recovery Center who needs transportation for treatment, we call them and they come down with their van.” The CORE Team also conducts staff trainings on topics such as overdose rescue and harm reduction strategies.

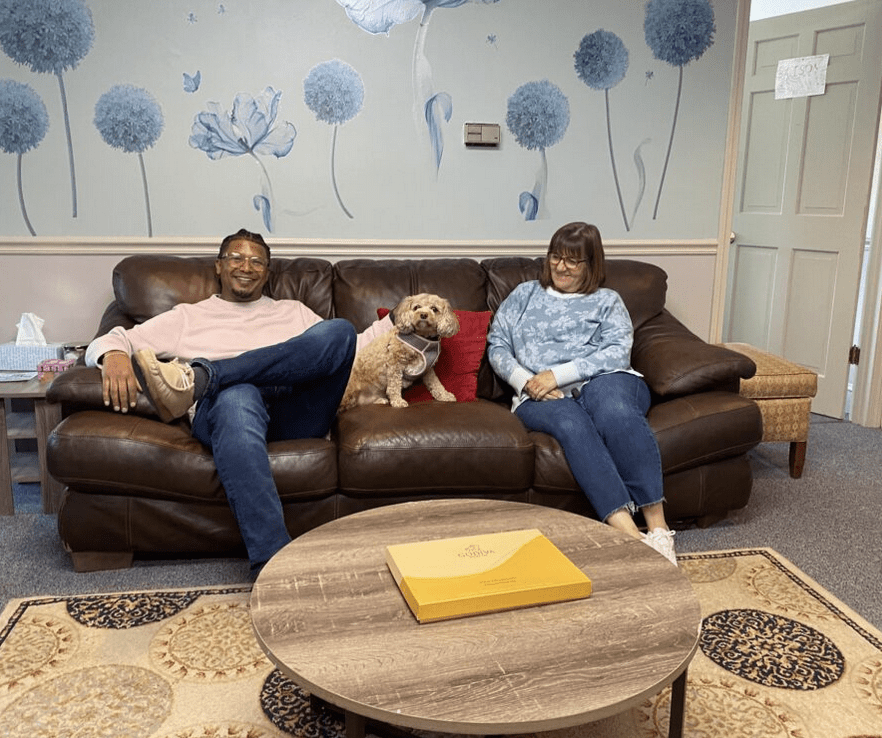

Sullivan and Jennifer Casey, CPRS, CCHW, recently gave Ocean State Stories a tour of the Middletown center. They were accompanied by Bailey, the center’s unofficial mascot, who likes to greet visitors and make them feel at ease. The center is light and airy, with spacious rooms available for mutual aid groups to meet. Coffee and water are always available for guests.

“We offer a safe space if anyone needs to come in,” Sullivan says. “If they want to talk with someone, that’s fine. If they don’t want to talk with someone, that’s fine. We’re a place for all people seeking safety.”

Which just might be the first step towards recovery.

For more information:

Center for Health and Justice Transformation

___

Ann MacDonald is a freelance medical writer living in Rhode Island. Earlier in her career, she worked as an editor at Harvard Medical School and held senior communications positions at several Boston hospitals. Find her at www.annmacdonald.net

Copyright © [2023] Salve Regina University. Originally published by OceanStateStories.org

Yet again myself and countless others are left out. I’ve been doing peer recovery work for years; I’ve dedicated my life to it. Not one time have I ever been involved in an article, interviewed, asked my opinion, or received a single accolade. It’s a wonder why the peer workforce fluctuates as it does. Very sad.