Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Our Networking Pick of the Week: North Kingstown Chamber at Tilted Barn June 16, 2025

- Business Beat: Residential Properties, Ltd (RPL) sales excellence celebrated at annual Top Producers Event June 16, 2025

- House Finance Committee’s FY 26 Budget boosts support for older Rhode Islanders – Herb Weiss June 16, 2025

- Business Monday: Employers need to learn how to “bust” ghostworking – Mary T. O’Sullivan June 16, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 16, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 16, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

The Plague and the Passion

Arthur P. Urbano, Professor of Theology, Providence College

In 1634, the residents of the small Bavarian village of Oberammergau staged the first performance of a Passion Play that would become a centuries-long tradition. It was the fulfillment of a sacred vow, a promise to God amidst the suffering of the Black Death: that this gift would be offered by the villagers of Oberammergau in perpetuity, if the plague was lifted and they were spared any more death.

According to tradition, the plague indeed ended, and, for nearly four centuries the Passion Play at Oberammergau has attracted pilgrims and tourists, eager to see and reflect upon the prayerful and dramatic reenactment of the final days of Jesus Christ.

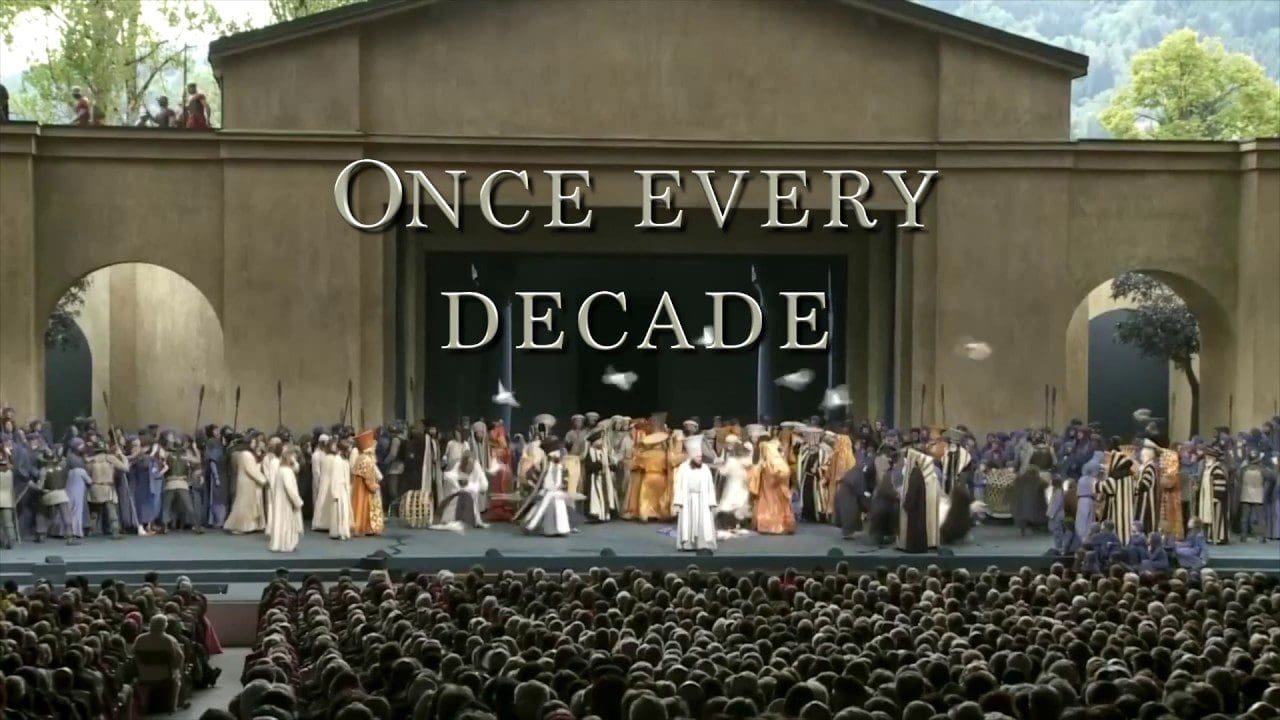

It is a huge production. Everyone involved—the actors, musicians, production team, all 2,000 of them—is a resident of Oberammergau. In recent years, the Play has been on a 10-year cycle, with the most recent series of performances being held in 2010. In the decade between the last performance and the premiere of the next series of performances (originally scheduled to begin this May), the village and the organizers of the Plato have been very busy. In addition, church groups and travel agencies have been booking hotels and tickets for the thousands of visitors planning on flooding the town of 5,200 residents between May and October. It goes without saying that the Play has a major economic role in the town’s life, as well as a spiritual one.

Preparations came to a halt in March when the organizers of the 42nd Oberammergau Passion Play announced that the more than 100 performances scheduled would be postponed until 2022 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. “The health of the population is a top priority for the community of Oberammergau and the directing team around Christian Stückl as well,” the press release reads. “The Corona pandemic has made it impossible to complete this year’s play without endangering the performers and guests.”

Another plague has halted Oberammergau’s perpetual gift of thanksgiving for salvation from a previous plague. However, this is not the first time the Play has been cancelled. It was temporarily discontinued under Prince Elector Maximilian Joseph III (1745-77), who considered the stage an inappropriate setting for “the greatest mystery of our holy religion.” In the wake of World War I, the 1920 edition was postponed for two years. The play was canceled altogether in 1940 during World War II, and resumed in 1950 with performances every ten years.

The Passion Play reenacts the Passion of Christ, his final days in Jerusalem recounted in the Gospels of the New Testament. Beginning with his entry into Jerusalem on a donkey (which Christians celebrate on Palm Sunday), the Play dramatizes all of the familiar scenes: the “Purification” of the Temple, the encounters with the priests and religious leaders, the Last Supper, the trials before Caiaphas and Pontius Pilate, the scourging and crucifixion of Jesus, and finally, his glorious resurrection.

Music, color, massive sets, and action draw the audience into Jesus’s Passion (the word Passion derives from the Latin word for suffering, passio) and Resurrection intellectually, emotionally, and, of course, spiritually. Catholic theology calls this the “Paschal Mystery,” the saving actions of Christ which are made present in the life, liturgy, and sacraments of the Church. It is interesting to note that the term “Paschal” is related to the Greek rendering of the Hebrew word for Passover, Pesaḥ.

Tragically, the beautiful story at the heart of Christianity—the self-giving of the Son of the God for the sake of his beloved human creatures—has often been intertwined with scapegoating and anti-Semitism. For centuries, Christians have ascribed collective guilt to the Jewish people for the death of Jesus. Historically, Jews have also been blamed for plagues and other societal ills. After seeing the 1934 production of the Play, Adolf Hitler had praised it for highlighting “the menace of Jewry.” Sadly, Jews today continue to be targets. The Anti-Defamation League[UA1] has reported the proliferation of anti-Semitic tropes on social media linking the spread of the coronavirus to Jews. An evangelical Christian pastor[UA2] said God was spreading the coronavirus in synagogues as punishment upon Jews for opposing Jesus. An Italian artist has resuscitated the anti-Semitic tropes of the legend of St. Simon of Trent, unveiling a new painting[UA3] as the coronavirus devastates Italy. Racist scapegoating has affected Asian communities across the world. In Texas[UA4] , two children and another relative were stabbed to death because the stabber “thought the family was Chinese, and infecting people with the coronavirus.”

Today the Catholic Church condemns all such expressions of anti-Semitism and racism. The 1965 document Nostra Aetate, issued by the Second Vatican Council, [UA5] was a major step away from the sinful attitudes of the past and the beginning of a new chapter in the Church’s relationship with Jews. Many other Christian denominations have made similar declarations. One practical outcome has been the periodic revision of the Oberammergau Passion Play. The most recent productions of the Play have brought Jesus’s Jewish heritage and the complex political context of first-century Judea into greater perspective. Jesus prays in Hebrew and a Menorah (though out of place for Passover) appears on the table at the Last Supper. This has been the result of cooperation among Jewish and Christian scholars and religious leaders who have worked with the Oberammergau writers and production team to revise the Play, attempting to eliminate the blatant anti-Semitism that had historically made its mark on the Play. Last fall at Providence College, we hosted an interreligious panel discussion[UA6] of the Oberammergau Passion Play as part of our series Theological Exchange Between Catholics and Jews[UA7] . The conversation centered around Catholic and Jewish experiences of the Play, and the impact of the Play on Christian-Jewish relations.

All of us are now living through a period of uncertainty and darkness. Celebrations of Passover, Easter, and Ramadan will be defined by social distancing this year. Although the Oberammergau Passion Play has to wait, the Paschal mystery which sits at the heart of the Christian faith assures us that new life follows death, light overcomes darkness, and good conquers all evil.

[UA1]https://www.adl.org/blog/coronavirus-crisis-elevates-antisemitic-racist-tropes

[UA2]https://www.rightwingwatch.org/post/rick-wiles-says-god-is-spreading-the-coronavirus-in-synagogues-as-punishment-for-opposing-jesus/

[UA3]https://www.timesofisrael.com/prominent-italian-painter-unveils-a-work-depicting-anti-semitic-blood-libel/

[UA4]https://abcnews.go.com/US/fbi-warns-potential-surge-hate-crimes-asian-americans/story?id=69831920

[UA5]http://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_decl_19651028_nostra-aetate_en.html

[UA6]http://www.thericatholic.com/stories/pc-forum-addresses-anti-semitism-in-passion-play,11201

[UA7]https://jewish-catholic.providence.edu/

Dr. Arthur Urbano, Ph.D. is a professor in the Theology Department at Providence College. Urbano teaches and publishes in the area of Early Christianity and Patristics. His research interests focus on the Christian reception and transformation of classical culture in late antiquity, particularly in the areas of philosophy, literature, and art.