Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Rhode Island Weather for April 29, 2024 – John Donnelly April 29, 2024

- Advocates, providers on new Nursing Home mandates – Herb Weiss April 29, 2024

- Rhode Island Weather for April 28, 2024 – John Donnelly April 28, 2024

- The Promised Land: a short story by Michael Fine April 28, 2024

- Ask Chef Walter: Gnocchi with Pesto lesson – Chef Walter Potenza April 28, 2024

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

The Moment Arm of the Universe – a short story by Michael Fine

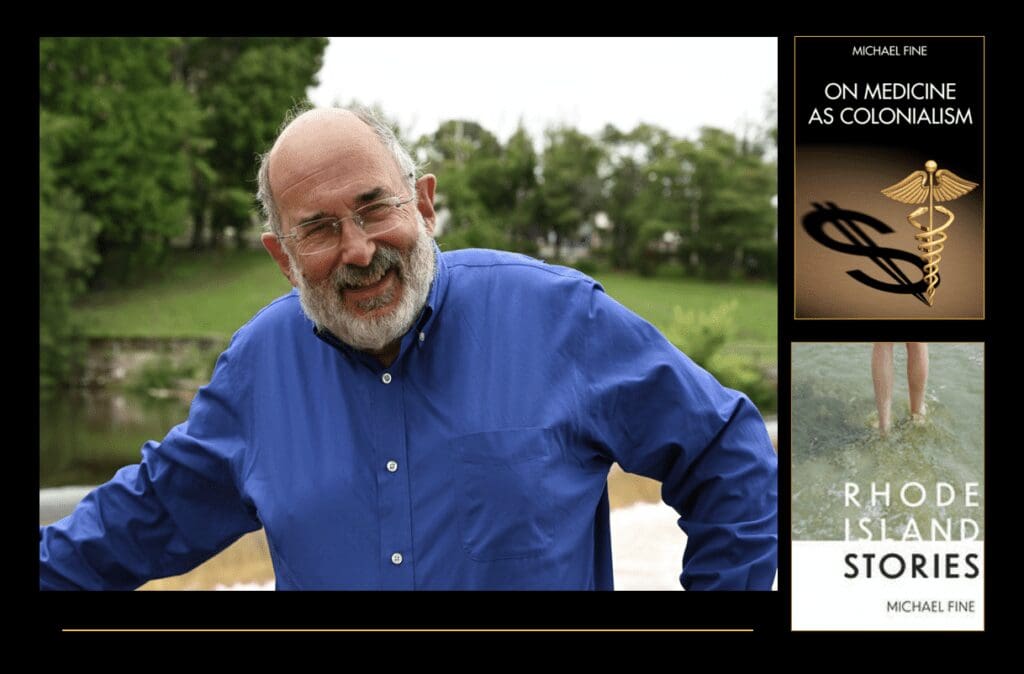

By Michael Fine, contributing writer

Copyright © 2023 Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

The Moment of a force is a measure of its tendency to cause a body to rotate about a specific point or axis. The moment arm or lever arm is the perpendicular distance between the line of action of the force and the center of moments.

A moment arm determines the influence of a force to produce (or prevent) the rotation of an object around an axis. Chris Luebkeman and Donald Petting. Architectonics. 1995, 1996 and 1997. Web.mit.edu. Accessed June 15, 2023

Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it, and I shall move the world. Archimedes

_

You don’t know what you don’t know. That was what Arch thought when his boy Hugo said to meet down in that park on the West Side, the one out past Silver Lake with that big hill on it where they got the skateboard park and the swimming pool and the inside court and a whole mess of outside courts now. You can’t change history. You play the cards you are dealt. The world turns with you on it, and you can’t do one thing about that, so you make the best of what you’ve got.

It was the summer of 1983. The Italians still owned both the Hill and Silver Lake. The first Dominicans and Liberians had started to sneak into the South Side, but no one knew they were there yet. There were plenty of Cape Verdeans and a few Brazilians snuck in among the Portuguese on Fox Point and in East Providence, and there was a little of everyone and everybody in Pawtucket, even French Canadians who spoke French, but nobody thought Pawtucket was a real place. It was the middle of deep nowhere, East Tahootz, from the perspective of people in Providence. Nobody said, you go to Pawtucket, you pack a lunch, because nobody in their right mind ever went to Pawtucket. They had that ballpark though. You could go to Pawtucket for a game in the summer, but not for anything else.

That summer was hot. There were hardly any trees in South Providence or Fox Point, and nobody had air-conditioning at home yet, so we all hung out on our porches, sweating up a storm, fanning ourselves and trying not to move much at midday if you didn’t have to go to work. You just waited for the sun to go down and prayed for a breeze off the river or the port.

Arch had a beat up 1967 Plymouth Valiant with a slant six engine and a column shift that you just couldn’t kill. He pushed his seat way back so he sat real low when he was driving through Silver Lake, his head almost below the steering wheel — just high enough that he could see over the dashboard and work the shifter. Things had eased up a little since the sixties but all that mess in South Boston had happened just a few years before, so Arch kept his guard up. Providence wasn’t Boston but it also wasn’t that much different. It is better to be safe than to be sorry.

He rolled down Plainfield Street at about six in the evening without incident, though there were plenty of people sitting out on their porches then, porches stacked three high, the men in their undershirts just off work from the jewelry factories on Dyer and Point Streets and the print shops on Prairie Avenue, the women with their hair put up to cool their necks. Nobody looked at Arch’s old car and nobody saw him inside. Or if they saw him, they let him pass. Maybe it was just too hot for them to give him a hard time.

He was thinking about what changes and what always stays the same. Things change over time. But does change matter? You see injustice, you see unfairness, you see inequality. People are piggish and stupid. You see the craziness of people who want to keep it the way it is, you see the craziness of the haters and all the people who are willing to fuck you up just for living, and you think, what are people good for? Then there are all those people who yell about the problems, who go on marches and carry signs, like yelling matters. Like some of them aren’t also out to make a buck for themselves at the end of the day. Is that all we can do? Watch football on TV, eat TV dinners or from chain restaurants, have our little life dramas, the dramas of women and men liking or loving each other or not, cheating or being cheated on, dramas that don’t mean very much. You wheel and deal and get pushed and prodded, all while just trying to get by, and you think, what is all this for? And then you think, no one person can change anything. People are about themselves. That’s just the way it is.

Hugo sat waiting for him in the parking lot. He sat on the hood of his souped-up Ford Fairlane, a nice two-toned job with tailfins and a front spoiler. That park wasn’t all built up yet the way it is now. They had some basketball courts and a scruffy looking baseball diamond but that’s about it. The fields around the courts were filled with junk – beer and soda cans, old baby carriages, plastic bags, empty oil containers, mangled bicycles, old newspapers, what have you. There were no lights over the parking lots or the basketball courts, so nobody came to that place, and nobody cared who was there.

“I got us a little work in Pawtucket,” Hugo said. “Follow me.”

“What do you mean us?” Arch said. ‘Who’s us?”

“You and me,” Hugo said. “Just the two of us. In and out. Won’t take twenty minutes.”

“What kind of work?” Arch said.

“Work. Just work. What does it matter if the money is good?” Hugo said.

“It matters to me. I like to know what I’m getting into, that’s all,” Arch said.

“We’re helping some old lady move, if you got to know.” Hugo said. “Time to pack up and go to the nursing home. Her daughter called me. Her son-in-law’s a lawyer. My girl works for them in Providence. Clean out the house. Fill up the truck. All her old crap is going to Goodwill. Fifty bucks each, under the table. In and out in twenty minutes. Maybe thirty. You see something you want for yourself, you take it. No questions asked. Cake.”

So, they drove to Pawtucket in two cars.

The house was up on Quality Hill, just off the S curve, near the hospital. People don’t know about the houses that are up there, all these big old Victorian places with circular driveways and stained-glass windows, houses that look like they belong on the East Side or in East Greenwich, but there they were, in Pawtucket. The sun was setting as they got there. The last light of the late afternoon, the light of long shadows, illuminated the houses and trees and made the blue and yellow paint on some of the houses intensely blue and intensely yellow, while it made the green of the maple leaves a dark, powerful, manly, rugose green and that light made the pale blue and purple of the hydrangeas growing in front of some of the houses and the red and yellows of the dahlias intensely pale blue, red and yellow, as it even made the shingles on the roofs of those houses stand out, one shingle clearly distinguishable from the next.

The house was the biggest and grandest of all the houses on Quality Hill. Three stories. Shingled wood, painted yellow and brown, with a huge, windowed parlor that looked out onto what had once been a formal garden. A big porch, wide enough to hold a living room’s worth of porch furniture in the summer, or to hold fifty people, though only cardboard boxes and furniture wrapped in bubble wrap and cardboard were on that porch.

They climbed the steps. It felt like they were ascending to heaven and were about to meet the heavenly host.

The doorbell looked like any other doorbell in America, just a little button, but when you rang it there were these deep and resounding chimes, bong, bong, bong, that sounded like you had died and were being welcomed into heaven by that heavenly host himself. Or herself. Or themselves. Whatever.

A woman opened the door. She was in her sixties, spare and angular, with long grey hair that fell to her shoulders and tortoise shell half glasses that were hung on her neck by a gold chain. She was wearing s single strand of pearls.

“Hugo? so glad to see you, so nice to make your acquaintance,” she said. “I’m Irma of course. Irma Klein. And this is…?”

“Arch. Archie. Archie Gomes,” Archie said.

“Welcome Archie. So good of you to come. Please do come in,” Irma Klein said. She had a slight accent that Arch couldn’t place, or perhaps it was a lisp. Regardless. She radiated money and elegance, comfort and privilege, like she was a woman who had never worked a day in her life and never would. But still had plenty of wants. She exuded ownership. And expectations.

The door itself was the widest door Arch had ever seen, at least three feet, maybe a full four feet wide. This will be cake, Arch thought, as he and Hugo stepped across the threshold, into the snazziest place Arch had ever been in in his whole life. The entry way was a big room all on its own. It was two stories tall and opened into a grand curved double-wide staircase with a huge dark wood banister that curved as it flowed downward from the floor above, like it was a waterfall frozen in time. There was a thick red oriental carpet on the staircase, and another carpet that showed the way from room to room. The windows were made from leaded glass and had a row of stained glass on top of them – pictures of flowers and birds. There were crystal or polished brass chandeliers in every room. The walls were wood paneled, and there were paintings on all the walls, pictures of people, mostly, but also art – landscapes and abstractions, lit from above by individual spotlights and by their own lights, like you’d see in a museum. Air-conditioned. So nice and cool.

“Let’s go to the kitchen,” Irma Klein said, and she led the way to the back of the house. Hugo raised his eyebrows as if to say, look at this place, brother. But Arch just shrugged in return. Same old shit. Different day. The kitchen, the garage, or the basement. That’s where people like him were always taken, when someone was going to give them instructions or directions. No surprise. But he got that message loud and clear.

As they walked down a long hall, they walked past a room with floor to ceiling books. It had a fireplace. At one end of the room, an old woman with white hair, wearing a dressing gown, sat in a hospital chair with a bed-tray in front of her, her arms locked on the arms of her chair, staring out at them as they walked past.

The kitchen itself was something to behold. It looked like a restaurant kitchen, not the kind of place normal people cooked and ate in. All the countertops were marble. There was a whole flock of shining pots that hung from a rack on the ceiling, a double stainless-steel refrigerator, a bank of ovens of various sizes, and a marble work island that had its own sink. The kitchen looked out onto a big garden behind the house and onto a grape arbor and trellises that overflowed with roses in bloom, still pink, red, orange and yellow in the waning early evening light.

“The movers can handle the furniture,” Irma Klein said. “I need help with some of the smaller items in the upstairs bedrooms, some of which will be given away, and with packing the books, most of which will be donated, but some are books I’d like to save. So, I’ll work with you, and we’ll go room to room. Does that work for you?”

“I thought this was a quick thing,” Arch said. “In and out in under an hour.”

“There must be some kind of misunderstanding,” Irma said. “I’ll need you for several days. It’s twenty-five dollars an hour, though. Does that work for you?”

“I can do tonight,” Hugo said. “But I gotta work tomorrow. And every day this week.”

“What about you?” Irma Klein. “Archie? Or is it Arch?”

“Arch. Just Arch,” Arch said. He thought for a moment about the old woman, sitting in that chair in the library as they walked by, looking at them, and hesitated.

“We can pay you in cash, of course,” Irma Klein said.

“I could do it,” Arch said. “The money’s good. I can move a few things around. Three days. You guarantee three days, and I’ll be here.”

“Excellent,” Irma Klein said. “Let’s get to work.”

They climbed to the second floor on a back staircase which started in the kitchen and ended on the third floor. The work itself, well, there was nothing to it. They each had two boxes, the ‘discard’ box and the “to be moved’ box. Arch or Hugo would take something off a shelf or out of a drawer and hold it up, and Irma who stood in the door, would say ‘keep’ or “toss’. When a box was filled, Arch carried it to the porch, where he made two piles of boxes.

Arch never would have imagined the things those people had, and he found himself imagining who lived there, what they were like when they were young and what had happened to them. The rooms themselves were pretty magnificent. Arch could not imagine himself living in such a place because there was so much space – the people who lived there must get lonely to be in those rooms by themselves, he thought, and that was as adults. Arch couldn’t imagine what it must have been like for a little kid to live in a place like that, in one of those rooms by themselves, because Arch’s own life had been made by having lots of people around and together, lots of people coming and going, talking and teasing and undressing and running to the bathroom and being in the bathroom too damn long – life being composed of the grunts and groans and laughter and smiles of the people around you, even when they were busting your chops, even when they were giving you a hard time, which was what they did, most of the time.

There was all sorts of stuff to be packed – pocket knives and cowboy hats in one room, dolls and hair combs and brushes in another, books and records and an old record player in a third – transistor radios, flashlights, baseball hats, hockey sticks, electric trains, little toy horses and cows and riding hats and fishing rods, and hooks and sinkers, but also old army hats and some metals and military insignia, and hair clips and hairbands and costume jewelry and posters of singers and groups Arch thought were long dead – the Beatles and The Rolling Stones and Jefferson Starship in one room, The Monkeys and all sorts of young men that Arch didn’t recognize and pictures of people who were older yet, glossy black and white 8x10s of people who were from another time altogether, who looked like they came from another planet. They had a couple of boys and a couple of girls at least, Arch thought. Some who had lived there were older than the rest. Maybe two people. There was no way to know just how old these people were or what kind of lives they had growing up or what kind of lives they had now, but Arch felt like one or two of them were serious people, serious kids, and maybe another was a girl who married young and another who had moved away young and never came back and still one more was someone who went off to war, but one thing felt certain: he felt their loneliness, their distance from one another, the way they must have felt lost up there, in these big rooms without one another, left alone to figure things out for themselves. He understood how they must have learned to comfort themselves, or not, and how some of them must have grown up to be rich and powerful themselves, the kind of people who know they are right, act with assurance, are ready and able to walk all over people who have less than they have – people who never look back.

Arch carried each box down the back stairs into the kitchen, out to the porch and thought about what he might lift for himself or somebody he knew from the boxes that were going to be given away as he carried them. He walked by the old woman in the library with each trip. There was a woman, a dark-skinned woman with her hair in a kerchief, who sat in a room off the library reading a book and who came and went in and out of the room with the old woman in it, so that the old woman wasn’t alone. That old woman looked at him each time he walked by, but she didn’t speak. That bothered him. On his second or third trip, he noticed that she was wearing a vest over her dressing gown, and that the vest was tied to the back of the chair, so she couldn’t slip down or fall. But that also meant she was restrained – that she couldn’t get up. Okay, Arch told himself. She’s old. And not in her right mind. So they’ve got her restrained for her own safety. I get it, he told himself. But I don’t like it. Doesn’t seem right.

They worked that night until after dark, Hugo packing most of the boxes and Arch doing most of the up and down, until there was a decent sized pile of boxes on the porch. Irma Klein paid them both in cash — $75 each, not $50, and not bad for a night’s work, not bad at all.

“What time do you want me here in the morning?” Arch said.

“Let’s start at 8:30,” Irma Klein said.

“I’ll be here,” Arch said, He and Hugo walked out the front door, passing that old woman one more time.

And then they each took off. It was going to be a little weird, working in that big place alone with Irma Klein the next day. But hell, Arch thought, there isn’t much I won’t do for $200 bucks a day under the table. I can stand almost anything for three days. And this gig was inside, where it was likely to be cool on a hot day. Not a bad deal.

It took a long time for someone to come to the door the next morning when Arch arrived. He rang the bell and heard the big chimes resounding inside that big entry hall and throughout the house as he stood on the porch, the early sun already gone by then, the day hot already, slowly burning off as steamy fog that was really a low hanging cloud bank that had rolled up from the Blackstone River, where Slater Mill lay next to the falls, and where the yellow church with the clocktower was, just a few hundred yards away from where Arch stood, in the river valley that had once been black with coal smoke from the factories lining the river, and the river itself had run green and brown, polluted beyond salvage by the dyeworks and the leatherworks and the spinning mills that once lay on both river banks.

When no one came after a few minutes, Arch rang again, and listened again to the bong, bong, bong of the chimes. He wondered for a moment whether he’d gotten the time wrong, and thought to himself, two hundred bucks a day under the table for minimal work – it probably was too good to be true. He waited another few minutes and heard footsteps coming toward him just as he rang the doorbell a third time.

The woman in the white uniform Arch noticed the day before opened the door.

“You may come in,” she said as the chimes faded away, in an accent Arch couldn’t place. Maybe Jamaican. Maybe Nigerian.

Arch stepped into the entryway.

“Upstairs?” he said.

“Wait here,” the woman said. “Or, you sit in the library.”

Arch followed the woman to the library, their footsteps echoing in the entry hall, figuring he’d pull a book or two down from the shelves and page through them to kill time while he waited.

But the old woman in the dressing gown was back again, back seated in the hospital chair with the bedside table in front of her and tied down by that restraining vest.

Arch sat for a few minutes on a chair with a reading light next to it next to an end table that held a black telephone. The hospital chair was pointed right at him, the woman’s arms still gripping the arms of the chair.

“You were here yesterday,” the old woman said at last. “I remember you. You went in and out, carrying boxes.”

“Yes m’am,” Arch said. He wasn’t much for sir, ma’m, and madam.

The old woman looked at Arch for the first time.

“They are stealing my house,” the old woman said.

“Ma’m?” Arch said.

“They’re robbing me blind. They got control of my estate and now they have the deed to the house and are emptying it. Carting off everything of value. The furniture, the silver, the paintings. Everything. They’ll cut this place up into twenty apartments and rent them all to people like you – immigrants, people who don’t have any respect, people who smoke and drink and what-have-you.”

“I’m confused,” Arch said. “I thought Ms. Klein is your daughter. Or daughter-in-law. Something like that.”

“She is my daughter. But she’s in with them. They got me bound and gagged here. Trussed up like a lamb to slaughter. Don’t you see?” the woman said.

Just then Irma Klein walked into the room. She looked exactly the way she looked the day before – every gray hair in place, an expensive looking blue silk blouse, a gray skirt and those pearls.

“How nice to see you again,” she said. “Arthur, isn’t it”

“Arch,” Arch said, as he stood up.

“You’ve met my mother, I see,” Irma Klein said. “Mother, this is Arch. He’s here to help me straighten things up. We’ll leave you to the books and magazines.”

She turned without waiting for a reply and marched out of the room, making it clear Arch was to follow, which he did.

“Nice to meet…” Arch said to the old woman.

“Don’t come back,” the old woman said, as Arch left the room.

“You’ll have to excuse my mother,” Irma Klein said. “She hallucinates. Alzheimer’s disease. And she wanders. And she harbors many… unfortunate… prejudices.”

“Not to worry,” Arch said. “I have a broad back. Sticks and stones.”

“Thank you for your understanding,” Irma Klein said. “And for your forbearance.”

They went back to packing boxes. But something didn’t add up. That old lady sounded bitter. Even mean. But she didn’t sound like she was out of it. And she didn’t look that crazy either.

They packed a box of fishing tackle for Goodwill. It was wimpy stuff – boxes of flies, tiny hooks, that heavy line used for fly fishing, some of those strange fly reels, and a couple of fly rods that were broken down and lived in a green cylindrical case about three feet long. No bobbers or sinkers. Some split-shot. Nothing that useful.

“You might like these things for yourself,” Irma Klein said. “It’s for the discard pile, but feel free to take it.”

“Sure,” Arch said. It will probably sit in a corner of my house for ten years, Arch thought. And then I’ll pitch it. But what the hell. “I’ll put it in my car. Might take me an extra minute or two.

“Not to worry,” Irma Klein said.

“You!” the old woman said, when Arch walked by the library, a box in one arm, the cylindrical fishing rod case under the other.

“You come here.”

“Ma’m?” Arch said.

“Come here right now,” the old woman said.

Arch came into the library. An older person asks for something, you listen. He was brought up right.

“Where’s your, what happened to the woman who sits with you,” Arch said.

“She’s no good. She’s outside smoking. None of them are any good,” the old woman said. “Put that box down. There. On the chair.”

Arch stood his ground. This wasn’t in the job description.

“Water. I want water. There’s a sink in that back room there,” the old woman said, gesturing behind her. As she gestured, Arch noticed that the old woman’s hands were tied to the arms of the chair. He looked at the skin of her hands and arms, which was almost white, wrinkled and as thin and delicate as tissue paper. Then he noticed the skin stretched over her forehead and her high cheekbones, which was also white, glistening, and so thin he could see the dark blue veins coursing beneath it.

He put the box and cylinder on the chair near the fireplace and went to get a cup of water. Man, these people are weird, he said to himself. This lady, mean as a snake. Her daughter, distant and queen-for-a-day. Who ties down old people? Not me, he thought.

He brought the cup of water back to the old woman and held it in front of her lips. She took a sip and he tried to tilt the cup just enough so she could drink, but a few drops spilled.

“You’ve spilled it! Untie my hands!” the old woman said.

Arch knelt and untied one of her hands. The old woman took the cup of water and emptied it into her mouth.

“More. Get me more water. They aren’t feeding me or letting me drink,” she said.

Damn, Arch thought. What the hell is going on here?

By the time he returned with a second cup of water, the old woman had untied her other hand and was clutching at the ties behind her that held the vest she was wearing to the chair.

“Untie me!” she said. “Now!”

Just then Irma Klein walked in.

“What’s going on here?” she said.

“I see.” She looked hard at Arch, a steely glaze that accused, tried and convicted him of high crimes and misdemeanors in a single instant.

“Everything is under control here,” she said.

“Julia,” she said loud enough to be heard anywhere in the house, clear but not shouting. A door slammed shut and the woman in the white uniform hurried back into the room.

“Everything is under control, Mother,” Irma Klein said. “You just sit back down, there, and we’ll tidy things up.” She grabbed one of the old woman’s hands in hers and forced it back onto the arm of the chair as the woman in the white uniform retied it. Then they did the same thing with the other arm.

“Now you are safe and secure. We don’t want you falling again and hurting yourself. And you, Arthur, you can go about your business, please. Take the box outside. Julia can manage here without your help.”

“Arch. My name is Arch,” Arch said.

“Arch then. Please do just what you’ve been asked to do. Nothing else. Julia doesn’t need your assistance. But thank you for trying to help.”

Arch grabbed the box of fishing gear and the cylindrical green case and carried them out to his car.

Man, he thought, these people are something else. That old lady, mean as a snake. And her daughter, who acts like she owns the world. Maybe there is something to the old lady’s story, about them keeping her locked up and selling the house and all her things out from under her. But then why was she still in the house? Why hadn’t they packed her off to some nursing home already? I’m just one guy, Arch thought. I can’t tell who is who. Is she in her right mind? Are they trying to rob her blind? None of that is my business. I got a good gig here. Two hundred a day, under the table. Let’s not look a gift horse in the mouth.

But later, as he drove home, it ate at him. That old lady, she was despicable. What if she was telling the truth? What if they had her bound and gagged and were stealing her life savings and her house, and all that shit. If they were doing that, didn’t that make him, Arch, an accomplice? Like an accessory to murder. Like the guy who drove the get-away car.

That night there was a thunderstorm at three AM. The thunder woke him. There was lightning all around that made the night look like day for moments at a time. Arch wasn’t sure if he was dreaming or awake. Then the rain pounded down, a close-in thrum, heavier than any noise a machine could make and all encompassing. Something isn’t right with that whole story, Arch thought.’ I don’t trust or believe any of them. They are paying me off to look the other way. I’m stuck between a rock and a hard place. And I got no good options here.

Then Arch fell back to sleep.

He woke early the next day. The summer sky lightened long before dawn, a kind of blue-gray hush, and everything was different shades of dull green. The birds called in the underbrush, their brilliant chorus still symphonic, back in the day when there were a zillion more birds then there are now, back when you couldn’t pick out a single birdsong before dawn because there were so damned many of them that they’d wake you from sleep with the first light.

Arch shook himself awake and went out to his car. The pavement was wet from the previous night’s rain. Droplets of water glistened on the leaves of the trees and on the grasses. There were puddles in the street and on low places in the sidewalk, and the now-clear air smelled like earth and growing things, as if the air itself had been washed and was fresh and clean after hanging out to dry in the rising sun.

–

He drove to Pawtucket. There is something conspiratorial about moving around in the early morning in the summer when everyone else is sleeping, when you can move about freely, when there is no traffic, when no one looks, and no one sees but you can see anything and everything. In those days, there were still milkmen who drove in the streets at that time of day, and junior high school kids working as newsboys, walking the streets with their big white canvass bags, tossing newspapers on every porch.

The bay windows of the big house and the leaded glass on the second floor caught the morning light and glittered in silence, as if it was covered in jewels. No cars were parked in its big circular driveway, and no one was parked on the street. Their cars must be in the garage, Arch thought, a big, detached affair that was itself two stories and had probably once been a carriage house, with a second story used to store hay for the horses. The milk box was on the back steps to the kitchen. The electric wires from the street were still wet, the water on them glistened in the morning sun. Drops of water fell from the big maples out front with the least breeze.

Arch sat in his car for a few minutes. He didn’t have a plan. This thing bothered him, that’s all. It was a knot he wanted to untie, not weight to haul up a hill. Then, what do you know, he looked in his rearview mirror and saw someone walking toward him, a woman.

When she was twenty steps away, Arch opened his door slowly so as not to frighten anybody. It was the woman who usually wore the white uniform, who was walking towards him wearing a bright yellow, red, and green summer dress, her hair up the way it had been the last two days and wrapped in a kerchief that matched her dress.

“You’re Julia,” Arch said.

“You’re early,” Julia replied. Arch still couldn’t place her accent.

“You walk to work?” Arch said.

“Walk from the bus,” Julia said.

“If I was going to be around longer, I could give you a ride,” Arch said.

“If wishes were Rolls-Royces, I’d always ride in style,” Julia said. She kept walking toward the house. Arch walked with her.

“What’s the story with the old lady?” Arch said.

“Which old lady?” Julia said.

“The old old one,” Arch said. “The one you’re with, who is tied down.”

“Mean as a snake. Don’t turn your back,” Julia said.

“She in her right mind?” Arch said.

“Are any of them in their right minds?” Julia said. “They pay me. I work. Don’t know a thing about their minds and I don’t care.”

“She says they got her tied down. That their stealing her house and her money, and so forth,” Arch said.

“They always saying that talkin’ stink mouth. All of them. I do my work and I go home.”

“You think she’s making it up?”

“She knows the day,” Julia said. “She knows me. She mean as a snake. What else do you need? The day will come when they all tied down. Can’t come too soon.”

Julia walked to the kitchen door and let herself in with a key.

Arch went back to his car. When eight-thirty came, he rang the front doorbell. The chimes sounded. Julia opened the door after Arch rang the bell a second time. She was dressed in her white uniform again.

But when the door opened, Arch didn’t see the grand entry way or that curved staircase or the crystal chandelier. Instead, he found himself looking at the great spread of stars in the night sky. He saw the Milky Way and the depth of the heavens. Then there was thunder and lightning. Day turned into night and night turned into day, just like what happened in that lightning storm the night before.

Then things flipped again, and he was back in that big old drafty house. That might look like heaven to some people. But that sure as hell didn’t look like heaven to Arch.

No one person can change anything, Arch thought. People make these big messes. Nobody likes things as they are. But nobody wants to change. People only think about themselves.

Arch couldn’t tell if that old lady was being held against her will. Or if the people around her were protecting her, doing what was in her own best interest because she could no longer take care of herself.

“You, there!” a voice called out, when Arch walked by the library.

“Arch. My name is Arch. Or Archie,” Arch said.

“I don’t care what your name is. You come here and untie me,” the old woman said.

“Nobody’s going to untie you until you treat people with a little respect,” Arch said. “I don’t know you from a hole in the wall. But I’m really done with you crabbing on me every time I walk by.”

“Arthur,” came a voice from the kitchen. “Is that you?” Irma Klein said. “We’re going to start on the second floor today.”

“Archie,” Archie said. “My name is Archie. I’m in the library.”

“Of course,” Irma Klein said. “I’m terribly sorry Archie. I’m so absent minded. I’d forget the name of my own brother if I wasn’t reminded of it from time to time.”

“This lady keeps telling me you people are stealing from her,” Arch said. “That she’s being held against her will. She’s nasty. But she isn’t crazy, as far as I can tell. I can’t tell who’s right and who’s wrong. But it isn’t my fight. I’m not going to get played any more. Move your own boxes. I’m done.”

Arch walked out of the library, out of the house, down the circular driveway, and got into his car, started it, and pulled away.

–

He drove back to the park in Providence where he met Hugo two days before, and sat for a few minutes in the parking lot, thinking, looking at the field strewn with rubble. Then he got out of his car and walked up the hill at the back of the park, just to blow off steam.

Now that was about the stupidest thing I’ve ever done, he told himself. Give up an easy two hundred a day in cash. Just because I didn’t like those people and how they treated me.

It took him ten minutes to reach the top of the hill. It wasn’t hot yet, but the summer sun was bright and strong and illuminated the landscape at Arch’s feet. There’s a little clearing up there. Some log benches and a fireplace, where people gather in the evenings to look out, because from there you can see all of Providence, the streets and the buildings and the cars and buses, and it all looks as small as it actually is.

What a mess we’ve made of the world, Arch thought. Of this beautiful place we’ve been given. And wrecked.

You can’t see even Pawtucket from here, though, Arch thought.

It was impossible to tell, even at that moment in history, if things would ever change, people being people. And if change would matter, if, and when, it came.

Give me a lever, a fulcrum, and a place to stand and I can move the world, Arch thought. But none of that is real. The universe goes on its merry way and all we can do is watch. See its beauty. And keep trying, each in our own small way, to do no harm, or better, to make things right. And taste and smell and see the air and the trees and the rising sun and the waxing moon and be damned glad we have this moment, this chance, our choices being as limited as they are.

And you never know, Arch thought. Maybe someday, one, or some, or most of us will get lucky, and things will get better despite the people we’ve always been. Despite our having no courage and no real place to stand after all.

___

Many thanks to Catherine Procaccini for proof reading and Brianna Benjamin for all around help and support.

Please click here to receive Michael Fine’s monthly short stories and his new series, What’s Crazy in Health Care. Please invite others to join by sending them the link here.

Information about Michael’s books, stories, posts, talks and performances is available at www.MichaelFineMD.com or by clicking the link here. Join us!

___

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor in Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.

He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.

He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.

Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.