Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Vinny Paz to be inducted TODAY into the International Boxing Hall of Fame – CES Boxing June 7, 2025

- In the News… quick recap of the week’s news (6.7.25) June 7, 2025

- Burn with Kearns: Strong without the spend: How scraps became strength tools – Kevin Kearns June 7, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 7, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 7, 2025

- How to advocate for threatened properties: The Heritage Alliance of Pawtucket June 7, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

The First Violinist of Lowden Street – a short story by Michael Fine

The First Violinist of Lowden Street

By Michael Fine

© 2018 by Michael Fine

(This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.)

To arrange the audition meant going places Sonia Bloch hadn’t been to for a long time, places she never thought she’d go again. But Alexandra Hijmosa was no ordinary student, and so it was worth opening old wounds and revisiting forgotten dreams.

Alexandra came to the Lowden Street house by herself one day in the early spring. She knocked. She was a slight girl carrying a violin case like so many others, about twelve, with olive skin, long dark hair, and shy deep brown eyes that darted away between glances. Was this a place of lessons, she asked? It was a question no one had asked of Sonia before. Yes, of course, Sonia answered, inpatient, because Alexandra had disturbed her as she was paying bills, an activity that Sonia hated. I would like to learn, Alexandra said. Who is this child? Sonia wondered, and she realized she must have appeared stern or even angry — but then no one had ever come to her door and asked for lessons in person. The mothers of prospective students usually called her to schedule a first lesson. Their children were almost always Jewish or Italian, Chinese or Korean. The women who called were the wives of doctors and lawyers, who were often doctors and lawyers themselves. They were second and third generation people, people who acted as if they had been in America forever, who spoke unaccented English and treated Sonia as if she were selling carpet or insurance; as if she had called them and not the other way around. As if she were not to be trusted. As if she were a servant or a tradeswoman. And not who she really was after all.

She brought the girl into her house and helped her off with her coat. Alexandra’s instrument was a disaster, but then no child’s violin is any good. The instrument had been found in a closet. It looked as though no one had touched it in forty years. So Sonia took out her second instrument and handed it to the girl. How did you find me? Sonia said, expecting to hear about a referral from the small city symphony orchestra where Sonia was a first violin, or to hear about a school friend who was Sonia’s student. I walk this way home, Alexandra said. I see the other kids coming out of cars. With violins.

In fact, there was a school a few blocks away, and there was also a neighborhood of recent immigrants and boarded up houses about a quarter mile away in a different direction, down a hill, and across a commercial street. A neighborhood of abandoned cars, broken pavement, and foreign grocery stores with garish flashing lights in their windows. Perhaps Alexandra had found her way to Sonia’s house completely on her own. Perhaps.

At least there were no bad habits to break. Alexandra had never held a violin. Sonia wondered if Alexandra had ever heard any of the music before. But she showed Alexandra, one small step at a time as she tried to remember how to talk about a process that, for Sonia, was as automatic as breathing. Tighten and rosin the bow. The strange and uncomfortable placement of the left hand, so the fingers can move about the strings. How the instrument is placed against the neck, under the chin.

Sonia remembered herself struggling to hold an instrument that was too large for her, in a cold room, in a four story walk up flat. On the street below, the trams ran every few minutes. Where you looked out and saw the leafless trees, tram wires, trams and many people in the street, in the cold, weak light of the northern winter. I want you to do nothing but hold the instrument for an hour a day until we meet again next week, Sonia said, doubting that she’d ever see the girl again. Let me show you one more time.

And then Sonia stood, feet apart, and lifted the instrument to her. She stayed perfectly still like that for a long moment, with no part of her moving at all so Alexandra could see how it was done. Then Sonia drew the bow across a single string, creating a single long D. Sonia played this single note, a note shaking with depth and overtones, a note that made every object in the room resonate, so that every picture frame and teacup, bowl and lamp shade trembled slightly with their own inner music. I’ll never see the girl again, Sonia thought, as Alexandra’s wide eyes turned from Sonia to the violin itself.

When Alexandra put her own instrument back in its case with hands that were still too small to play, her movements were careful and quick, as if she were handling an ancient family bible, an object of reverence. She doesn’t know you pay for lessons, Sonia realized, as she gave the girl a time for the next week. Then Sonia stood at the storm door and watched the girl walk down the walk to the street. It’s only a few minutes, Sonia told herself. These people are new in the country. They have different music. Different traditions. Sweet child, but clueless. She can’t do much harm with that instrument, but it will frustrate her. She won’t be back.

It is strange to remember and strange to live again in the memories that come back without effort when you least expect them. Her own beginning was completely different. Sonia had emerged in a world of buildings, of trams and books and of the music everywhere. She remembered her parents taking turns reading stories to her at night, and she remembered Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven along with the stories. Although now she could remember the melody and the phrasing of the music more clearly than she could recall the stories themselves. Peter and Katrinka. Ice skates. Racing on the ice. Little boys falling through the ice. Mozart Concerto #4. Handel Concerto Grosso Opus 3 #4 in F. The Last Quartets. The radio and their record player which Sonia’s father valued more than anything else, the records smuggled in from Moscow and Tel Aviv.

She was four. Her father didn’t play well. The instrument came from a pawn shop. He bought it early one spring when there was no food in the stores to spend money on. In the days before he lost his position at the university and began to work as a clerk in a dry cleaner’s, before he left for America. The seam between the back and side was open, and the fingerboard had come off. Sonia’s mother was angry when he first brought it home. Wasteful, she said, just fantasy. We need bread and meat. But Sonia’s father, who could fix anything, found a friend with hide glue and he and his friend put the instrument back together and then there it was, restrung, ready to play, and almost as big as Sonia herself.

One night, when Sonia’s parents’ friends had gathered and two of their friends were playing, Sonia lifted the violin. Four. She was only four years old and it was way past her bedtime. She stood up on a chair and said, I will play for you now a concert. Her parents and their friends laughed and applauded. Her father helped her hold the instrument for the first time. Sonia was so small that her left hand could barely reach the top of the violin’s sound box so her father stood behind her and held the fingerboard. Even then the bow was too heavy for her small hand, so her father reached around and held her hand in his as he held the bow for her and placed her hand and the bow on the strings. But it was Sonia who drew the bow. Her father, in his wisdom, angled the bow just right. Sonia could still feel the heat from her father’s warm chest as a note that was bigger than the whole house filled the room and spread through her body, sweet and clear and long.

The girl came back ten minutes past the appointed time. The narcissus was up against the white fence but had not finished blooming, and the sand on the streets that had been used to create traction when there was ice everywhere had not yet been swept away by rains and by street sweepers.

Alexandra was wearing a red spring coat that was too long and too thin for the coolness of the day. Sonia helped her off with her coat and went to the kitchen to turn on the electric kettle so she could make Alexandra a cup of tea. When she came back to the parlor, Alexandra had the instrument out of the case and was holding the violin exactly as Sonia had shown her to hold it. She was standing in the window, so the slanted warm yellow light of later afternoon bathed her face and upper body. When Sonia came into the room, Alexandra drew the bow over the G string. The note was long and clean. Then the girl up-bowed, a stirring and clear A. Sonia inhaled with the up-bowing and that breath, which was a breath of pure pleasure, now suffused her body, so she stood taller and fuller than she had a few moments before. I did not tell you to play, Sonia said. I told you to just hold the instrument, nothing more. An hour a day. I did not give permission for the playing of notes. The little girl lowered the instrument, her face deflated, and Sonia hoped that the girl was not able to see any of the pleasure that Sonia felt in her face or the joy she felt inside herself. They do not know punctuality or how to follow directions, Sonia thought. She will not be back.

Alexandra came the next week at the appointed time. It was raining hard that day, and the thin red coat was soaked through. Alexandra’s plain white blouse was grey on the shoulders, front and back now, glistening wet and cold to the touch. I’m getting you something to wear, Sonia said, and she brought a thick wool sweater from her bedroom. Change into this, Sonia said; the bathroom is down the hall, the second door on the left.

The girl was ludicrously thin, lost in that sweater, Sonia thought, as she put Alexandra’s blouse into the dryer. But this time the girl stood and played all the open notes. Her blouse had dried by the time their time together was over.

It wasn’t perfect. It never is. One day, Alexandra came early enough to see the previous student, a blond boy of twelve with a future as a scientist or a soccer player, finish his lesson. She saw the boy’s mother get out her checkbook, scribble on it, tear off a check and hand the check to Sonia before they walked out. Sonia could sense Alexandra brooding about what she had seen. Alexandra was tense and distracted all during the lesson. Sonia waited for Alexandra to ask about what lessons actually cost but the child didn’t seem to have the words she needed. Sonia thought, this girl needs to learn about how the world actually works, although Sonia wanted neither to cause the girl embarrassment, nor wanted to let the girl off the hook.

In the summer, Alexandra missed a lesson, confirming what Sonia already knew. She’s had it. She’s done. No discipline. They don’t know anything about this music. Why should she care? Her people listen to salsa and country music on the radio or top forty hits, and that is enough for them. She had wasted time giving away free lessons to a girl who could not possibly benefit from the attention. Just more wasted time in a life wasted on pursuits that went nowhere.

But the next week, Alexandra appeared at the appointed time. No words about the missed lesson passed between them. I am going to the Cape for two weeks, Sonia said at the end of the lesson. Here is your assignment, week by week, so I will see you not one, not two, but three Tuesdays from now, at the usual time. I expect you to be on time. If you must ever miss a lesson again, you must call me the day before. I require twenty-four-hour notice.

And then something occurred to Sonia. She went into the kitchen where she kept her business cards and brought back a card and a pencil. This is my name, Sonia said. And this is my telephone number, she said, as she circled her number on the card. They had been working together for four months, and Alexandra didn’t know the first thing about her, and Sonia didn’t know the first thing about Alexandra. Then Sonia went back to the kitchen and found an index card. Write your name, address and telephone number here, Sonia said. That way if I ever have to cancel, I can call you the day before as well.

That card, written in pencil, in block letters that were not precisely formed, would live ever-after on the corkboard next to the telephone in Sonia’s hall. Next to the cards of the plumber, the electrician, the taxicab company, the police and fire departments and the number of the rescue, on the corkboard, where Sonia’s eye’s rested whenever she answered the telephone.

In two years time, Alexandra became brilliant, the student all teachers wish for, the student who would surpass her. Alexandra was not a great violinist by any means. Not yet. But she was a great student. She learned quickly and somehow in her fingers there appeared emotion, the one aspect of musicianship that Sonia did not know how to teach. This girl who barely spoke and whose command of English wasn’t certain understood in some part of her what the music meant, and that understanding came out through her fingers and in her phrasing. Her technique was good, yes, and she rapidly developed the strength and dexterity to play; strength and dexterity that comes only from practicing three, four, even six hours a day. But this girl had something more. She had the music hidden in her soul, and it sprang from her as if it were caged and struggling to be released from this thin, simple, lost body.

Sonia was a good teacher, but soon Alexandra would need a great teacher. Someone who could frighten her and drive her, but also a teacher quietly connected to great performers and great orchestras. A teacher quietly sought out by the world’s great ones, who come from far away to take a private lesson, looking to find a new tone or polish a texture so they can go from confident and musical to great and stirring; from polite applause to twenty minutes of a standing ovation. She would have to go to Boston or New York to live, and she would have to give her whole life to the music, to do what Sonia had been unable to do, and to realize what Sonia had been unable to realize.

Sonia’s first teacher had made those connections for Sonia when she herself was twelve, just a girl living in Buda. She had been thin herself, thin and quite pale, just old enough to understand the paleness of her parents and know the meaning of the numbers on their arms, and just aware enough to know their anxieties and sleeplessness, which had become her sleeplessness and her anxieties. She was old enough to remember the red stars, the red flags, and the huge public statues, and also old enough to remember when the trams ran every five minutes and were free. Old enough to remember always knowing that there were many places and many schools where she could not go because of who she was, but too young to remember the Russian tanks when they rolled through the streets in 1956. There was always music in their flat, even when there was little joy.

Sonia’s first teacher brought her to Simhousen when she was twelve. The great man looked through her as she took her instrument out of the case. Is this one strong enough, she sensed he was asking himself as she lifted her instrument out of its case. He was thinking, will she stand up to what I am going to demand that she do, or will she crack? On top of everything else. In spite of it. In those years no one spoke of what they had lived through because all of them had lived through it and words conveyed nothing.

But Simhousen was shocked when Sonia played. She was so thin. Simhousen was accustomed to precision from students brought to him to audition. He knew virtuosity. But Sonia surprised him. The story of what they had experienced came through her even though she had not experienced any of it herself. The pain. The fear. The loneliness. The cold and the starvation and the exhaustion. The loss. The endless losses. Their survival, yes, the survival, but only as a fragment of what had been before. A whole world, entirely lost. It was all there in her playing. Miraculous. Simhousen stood up while she played, and then he paced. Five years of work, endless work, he said. And then perhaps. Only perhaps. I am not certain she will last.

This time the great man was a woman, Vivienne Liung. She was ten years younger than Sonia and was better known as a teacher than she was as a performer. She had studied with the great teachers who taught Sonia’s generation, she had performed all over the world, she had won the major competitions and then she had withdrawn from performing to teach. She had also studied with Simhousen, though in the last years of the great man’s life.

Vivienne was coming to Providence in November for thirty-six hours as a guest soloist with the orchestra. The orchestra would rehearse on its own for six weeks before the performance and then would rehearse once with Vivienne the night before the concert. Vivienne would give a master-class in the early afternoon on the day of the concert. Then a radio interview. Then a stop at Brown to be on a panel. Then a performance, and then off to New York by train in the morning.

Sonia, who had been first violin in the Rhode Island Philharmonic for 30 years, heard in May that Vivienne was coming. The pieces were announced, the scores distributed, and the orchestra would begin rehearsals for those pieces in early October. It was a hobby, playing in that orchestra. A little orchestra in a little provincial town. Just to keep her hand in it, and to attract students. Teaching kept Sonia alive now.

There was an intermediary in London, a friend who Sonia had played with in Budapest before she emigrated. Emails went back and forth. I have a promising student Vivienne should hear. The friend in London had to remind Vivienne who Sonia was, who she studied with, who she had been and who she could have become.

Vivienne finally responded. There are a few minutes in the late afternoon. Have her come to my hotel. Have her prepare three difficult pieces. She should expect me to grill her. To push her. To try to break her. There is some of the old man in me, Vivienne wrote, once she understood Sonia’s lineage.

By this time, the girl had become more presentable, but there was still a part of Alexandra that Sonia didn’t know. Many parts. Alexandra had achieved technical mastery of all the pieces Sonia rehearsed with her. She stood correctly. She breathed correctly. Her tone was perfect and her phrasing was immaculate, so good that Sonia didn’t understand how she had come by it. As her technique improved, Alexandra had learned to look the part of a performer. Sonia brought her to hear the orchestra when they played, to rehearsals and to performances, picking her up in front of her house in that neighborhood that was both close by and very far away, and dropping her there after the performance, before Sonia joined the others for coffee or vodka and to decompress. Alexandra took a black skirt Sonia gave her, added a white blouse, and learned to look perfectly respectable. Her long dark brown hair was now brushed back and hung almost to her waist, reflecting the order and luster of hundreds of brush strokes. Her ochre skin added depth to the whiteness of her blouse and her almost black eyes, opaque and subterranean at the same time, made her appear close and mysterious at once.

But Sonia didn’t know how Alexandra lived. Sonia had never been in Alexandra’s house, which was on an ignored street that few people knew. It was a pale green and grey-white triple-decker with almost no yard, a broken up cement driveway that had a grape arbor in front of it made from old iron pipes. The tiny porch with three rotting steps and no handrail led to two doors. Next to each door was a line of doorbells and name plates, but most of the name cards were scratched out, written over or just blank. Alexandra was almost always on the porch, outside, waiting when Sonia came for her. When Sonia let her off at home after a concert, she stayed in front of the house, the car running and the lights on until Alexandra had the key in the lock and the door open, because there was no working porch-light, and because, well, just to be safe.

And Sonia didn’t know Alexandra’s people. No mother had ever brought Alexandra for a lesson or picked her up after the lesson was over. Alexandra answered the door herself whenever Sonia rang. No one else – no sister, father, uncle, or a grandmother ever came to the door to say Alexandra will be down in a moment, why don’t you come in.

The concert started at eight. Come to my hotel at 5:45 and I’ll listen to your student, Vivienne had written. The hotel is next to the Vets. I’ll listen, and then we can walk over to the concert hall together.

I’ll come and get you at five, Sonia told Alexandra. Be ready, Sonia said. Don’t be late. Dress appropriately. Everything depends on this day.

As she drove to Alexandra’s house on the day of the audition, Sonia remembered how she thought her life would be after Simhousen, after the great man blessed her, and how different her life was from those dreams. She thought, I will practice all the time. I will perform in Budapest but also in Prague, Vienna, Berlin, Frankfurt, Moscow, Venice, and Tel Aviv. And then in London, Boston, and New York. I will have a large airy flat overlooking the Danube with its own practice room, and I will marry a conductor or a great cellist. We will have a country house and before long I will teach master classes of my own and learn to frighten the best students so we keep finding and training the great ones, frightening off those without an inner being made of steel, and leave the others to give lessons or play in the orchestras of small cities or to do something else entirely, to become computer programmers or dermatologists or engineers.

Sonia practiced all the time. She won the competitions that must be won. She performed with the orchestras and got the kind of reviews soloists dream of. One step led to another, which was certain to lead to a third. First a chair in the orchestra. Then a solo career.

But when Sonia was ready to step up, all the chairs in the orchestra were full. None of the violinists were retiring. The generation who Sonia should have replaced had been killed off or had fled twenty years before. Those who filled their seats, whose playing was perhaps not at the level of the pre-war years, were in those seats none-the-less and didn’t plan on leaving for another twenty years. Prague or Moscow, perhaps. But nothing at all in Budapest.

Then there was political turmoil, and with turmoil came years of shortages before the wall came down, and then came a few years of chaos and more shortages.

But the established pathways to a secure place had fallen apart. You couldn’t go simply from Budapest to Moscow anymore, and in Moscow earn the respect needed to travel internationally. Instead, you had to emigrate and start all over in London, New York or Tel Aviv.

And then it suddenly became possible to travel and even to emigrate.

Sonia met a chemist after one of her performances, a chemist who knew the music. When Leonid courted her, he promised London and New York. But after they married, and there was Sasha and Karl, they came to Rhode Island, not New York, for a university position. With the university position came the undergraduates and the graduate students, too many of whom were young women, and then, in a flash, Sonia’s imagined life was gone.

Sonia parked outside Alexandra’s house. There were no lights on inside the house, but there was still daylight. Alexandra was not waiting on the porch. Sonia honked her horn. It was five of five. There was still time.

Vivienne and Sonia walked together from the hotel to the concert hall.

We know that only a very few will progress. The process of finding and training those few is long and difficult. The life itself has many limitations. Many doors have to be closed along the way. The discipline is withering. Some doors can never be imagined. There is no shame in trying, in testing.

Vivienne and Sonia did not speak of these things, of course. They spoke only of Simhousen. They both remembered the strength of the great man’s grip when he shook a person’s hand, and the power of his embrace when he hugged you after not seeing you for a long time. How when he held you, he seemed to be holding onto life itself.

Sonia, before and after her apology, could not think and she could not feel. Her ability to feel anything ended forever while she was standing on that porch, as she rang the bell and knocked on that door again and again at five-fifteen, until five-thirty. A short bearded man in a tee-shirt, wearing only green plaid undershorts, stumbled to the other door barely awake, or barely sober, or both, having been woken by Sonia’s voice and her persistent hard rapping. No here, he said, when he saw her knocking on the other door. No home. And then he turned away, closed his door, and walked back up the stairs.

Even so, Vivienne treated her with respect. Sonia had studied with the old man. Vivienne knew now who she once was and who she could have been.

The concert-master came on stage as the orchestra was warming up, each instrument making a note or two to test the precision of their tuning. Together they created a bright cacophony of hopes and expectations. The concert-master stood, raised his bow, and the instruments quieted. He sat. The conductor came on the stage to applause, and waved and then bowed. Then the conductor went to the microphone and said a few words about the program and each piece. Then he introduced Vivienne, who took the stage confidently, wearing a low-cut black silk dress and pearls and stood in a spotlight, waiting her cue.

Sonia sat stage left, in the row of first violins.

The conductor raised his baton.

Sonia drew her bow across the strings. The note Sonia played was sweet, long and clear. It came not from her instrument but from inside Sonia herself, from her chest and pelvis, from her belly and her back, from her thighs and shoulders. Her body and soul wrapped itself around that note, perfecting its pitch and intonation as the note went free, tuned by every part of her. Sonia hated Alexandra in that moment and loved her. She hated life and loved it.

The note joined itself to the timber and tone of the orchestra’s rising sound, which felt as if it was ascending to heaven itself. And then it disappeared.

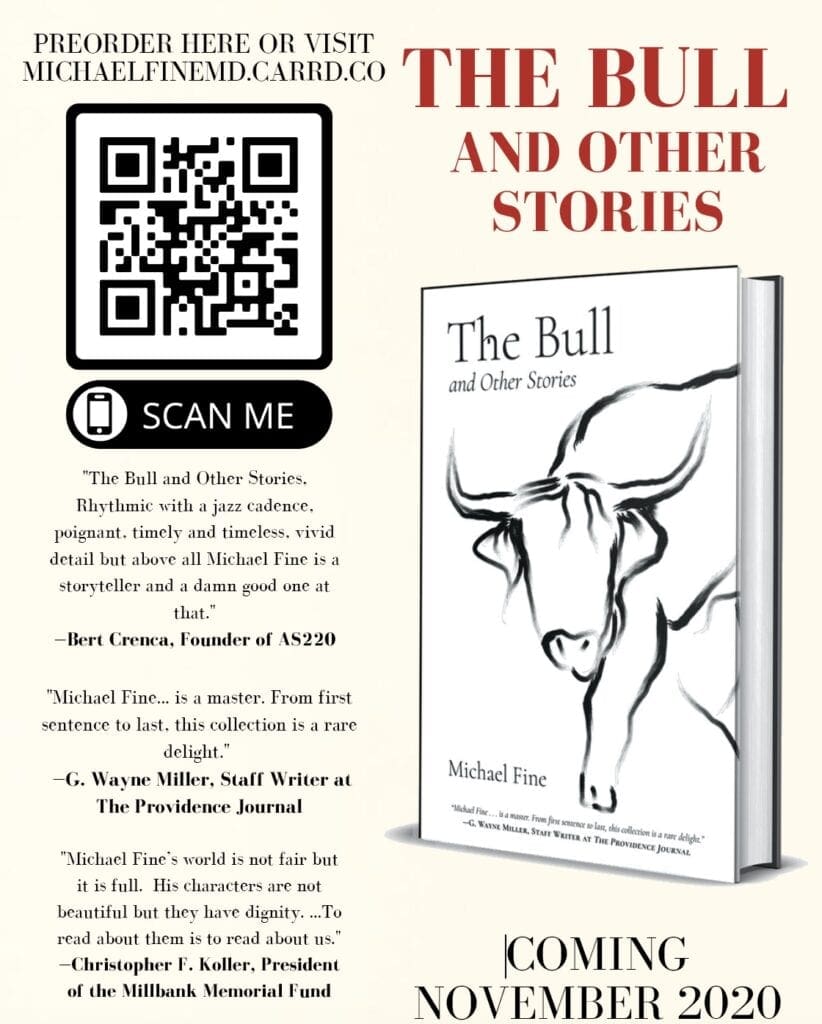

All of Michael Fine’s stories and books are available on MichaelFineMD.com or by clicking here.

__________

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor to Mayor James Diossa of Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.

He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.

He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.

Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.