Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Vinny Paz to be inducted TODAY into the International Boxing Hall of Fame – CES Boxing June 7, 2025

- In the News… quick recap of the week’s news (6.7.25) June 7, 2025

- Burn with Kearns: Strong without the spend: How scraps became strength tools – Kevin Kearns June 7, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 7, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 7, 2025

- How to advocate for threatened properties: The Heritage Alliance of Pawtucket June 7, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

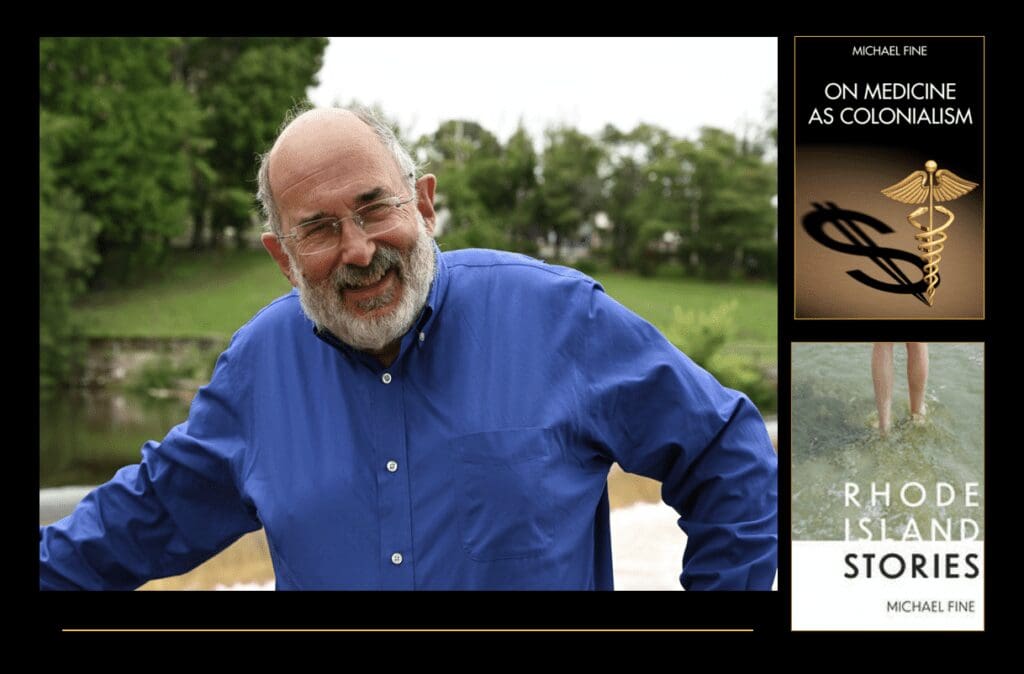

The Diving Reflex: A short story by Michael Fine

by Michael Fine, contributing writer

© 2024 Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

You’re not dead until you’re warm and dead. Every ER doctor knows that. Heck, every EMT and medical student knows that. People who drop their core body temperature from being submerged in cold water (or from exposure to the elements) may survive prolonged periods without breathing or a heart rate. The metabolic activity of the brain, which requires huge amounts of oxygen to survive, slows, and allows the brain to survive without oxygen, even when the blood isn’t flowing. You can’t go bankrupt if you are already broke. Or something like that.

It turns out that there are several coordinated reflexes that the body uses to protect itself when it is submerged in cold water, as if we were designed for deep water diving. Fall into cold water and three things happen at once. The heart slows and may even stop. The arteries in the arms and legs constrict, turning the limbs white or blue, forcing blood into the thorax and the head. The spleen releases stored red blood cells. The metabolism of the brain slows. These changes, called the diving reflex, mean you can survive longer than four or five minutes of no or limited heartbeat, perhaps as much as an hour or a little more, assuming you are found and promptly resuscitated. And so a person who is found in cold water or exposed to the cold is warmed as we attempt to resuscitate them. And more than you might expect, survive.

All very dramatic. And curious. Why? Because the diving reflex, this process of changing circulation around and slowing the metabolism, is found in every mammal from the duck-billed platypus to the largest whale, and is also found in ducks and penguins, in diving birds and other air breathing organisms. It is highly developed in human babies, who appear to be able to swim underwater without being taught until they are six months old, a complex set of reflexes that include the diving reflex and other physiological responses.

What’s most curious about all this is it exists in humans at all, even though we aren’t often divers, and we aren’t often submerged in cold water, or left out in the elements alone. The diving reflex was important to some distant evolutionary ancestor, perhaps. But it is not meaningful to us now. It is a part of our physiology that evolution just failed to extinguish.

But in the diving reflex we see a strange connection to the other species with whom we share the planet. Whales, dolphins, seals, sea lions, ducks and penguins have a use for the diving reflex – it allows them to find food and to evade predators. But humans? From the diving reflex we learn we are related to one another and to many other creatures, at least through a shared distant history. Etched into our bodies and our physiology is a clear and present reminder of who we are and where we came from. And that we are not alone.

If our bodies carry this kind of reflex, which can preserve life when all else has failed, what other reflexes surge within us unseen, influencing our choices and reactions, connecting us to one another and the natural world, while revealing unseen abilities, limitations and connections? That makes our future seem as unpredictable as our past feels dark and locked, our current life stuck because we are so limited by our weaknesses, limitations, corruption and lusts.

When Malcolm Murray saw the bullet go through Trump’s ear, he restrained his baser instincts, and didn’t let himself think what a part of him wanted to think, deep in his heart. People can’t go around shooting each other, he told himself. That’s civil war, not a political campaign. He thought the same thing when he saw Trump yell “Fight! Fight! Fight!” And yet he couldn’t believe it when he heard that someone had seen the shooter climbing up the building he used to fire from, and pointed him out to the police, and no one did anything. When he heard there weren’t sharpshooters on every roof around where Trump was speaking. And then when he heard that Biden had said, put a target on that guy. What are we coming to?

Civil war is what we are coming to. Or, what we’re asking for, if we keep up like this. What is everyone thinking? Are there no adults in the room?

That night Malcolm couldn’t sleep. So he got up before dawn and got in his car.

Buttonwoods was blue before dawn, a hushed, almost holy blue, the air under the few trees the color of trust and competency. There was just one bird, a Carolina wren, he thought, it’s fluty call plaintive and lonely in the lovely blue hush. Once upon a time there would have been an orchestra of birds in the early morning, Malcolm thought. Now just one. What have we done?

The cars parked in all the driveways glistened, coated with dew. The sky, though beginning to lighten, was still dark, so he could just barely see the neighbor’s houses, these quiet Capes and ranch houses, the few split levels scattered in between, the lawns mowed and most of the bushes trimmed, some driveways with two cars, some with a car and a pick up, some with boats and others with trailers – these were the houses of working people. Regular people, people with their own dramas and challenges but most of whom worked every day, if they hadn’t retired yet. Cops and firefighters. EMTs and nurses. Firefighters married to nurses. School teachers. School teachers married to cops and divorced from them. Their kids lived close enough to walk to school but rode the bus, drove or got driven to school anyway. Those kids played sports. Their parents watched. Little league and soccer and Pop Warner football were all things. Travel teams in the summer, for those kids whose parents had a little money. People made out okay, went out to eat, took vacations, and went to the beach. No one was getting rich. The planes from the airport took off and landed. Trains came and went across the bay. You could hear them in the distance. If you listened, you could hear the trucks on 95, a distant grind.

But not yet. It was still too early for all of that.

There was a waning quarter moon in the western sky which was still dark.

Malcolm drove south. I can get to Scarborough before the sun comes up if I hurry, Malcolm thought. I want to be on the beach before sunrise. And look out at the ocean and see the horizon, standing on the beach in a place where I can look towards Africa and Europe with my gaze unimpeded. Look out and see the horizon and the sea. And see nothing made by humans, lived on by humans, or touched or destroyed by human beings. Because we destroy everything we touch.

The whale lay on its side.

He thought it was a rock at first. In the dim light before sunrise. And that the tide was out.

There are rocks like that on some beaches, like those off the one beach in Little Compton near that beach club for rich people where folks like Malcolm weren’t welcome. Those rocks, those huge stone formations, rise up out of the sea and tower over the water, tiny mountains surrounded by beach, magnets for young boys to try to climb and dive off, a swimmer’s nightmare, because you never want to be dashed against those rocks by a wave. Those rocks were the demise of wooden ships in days of yore, when a storm or hurricane threw ships on the rocks, splintering them so that they could be swallowed by the sea.

But there aren’t any big rocks on the beach at Scarborough, Malcom thought. There are some rocks at the far end of the beach at East Matunuck. But not here.

He got closer.

There were no footprints in the sand yet. He was the first person to walk the beach that particular morning. It didn’t make sense to him yet. What was a huge blue-gray rock doing on the beach at Scarborough? A huge rock stuck near the lifeguard platform, itself a sad skeleton, standing alone in half light on the beach.

Then the thing, that rock, gave a huge sigh, as its chest lifted and then collapsed, as air and steam rushed out of it’s blowhole, a hiss a litte like a bus letting go of its airbrakes, but more like a deep sigh.

Holy Moley, Malcolm said to himself. I think I know what that is.

The whale lay on its side, one side flipper buried in the sand, the other sagging on its thorax. The whale was immense. Bigger than he imagined whales, or any living thing, could be. Bigger than his house. As long as a small jet but with four times the bulk. The size of a small car ferry. Three men his size, standing on one another’s shoulders with the man on top raising his hand wouldn’t be as tall as the whale was broad, laying on its side. Longer than a tractor-trailer. But as big around as three or four of them.

Its great chest rose again, slowly. And then collapsed, with a rush of air blowing out the other side, a whoosh like a sudden puff of wind in the trees, or the slipstream from an airplane taking off close by.

This thing is alive, Malcolm said to himself or maybe even out loud. And thinking.

The whale’s skin was crusted with barnacles. It had ridges, like the streamlining of a fifties car. But the skin was still smooth and glistening, and soft, like the skin of a woman’s thigh after she’d just showered.

Malcolm looked around. There was no one in sight yet. No cars on the road near the beach. No cars in the parking lot.

The whale’s chest lifted again. And fell. There was another rush of spittle, air and steam out of its blowhole.

What do you do? Who do you call?

Malcolm started to walk around the whale, thinking, maybe the tide will come back and lift it so it can swim away.

But then he said to himself, Malcolm, you idiot. No whale in its right mind, no whale that is healthy enough to swim, lets itself get beached. It has to be near death already. Leave it to itself and this baby is finished. Let this great creature die in peace.

Then he saw the whale’s eye, its great, sad, wise but tired eye, almost the size of a baseball, a deep black pupil with a thin rim of white iris. The eye of a whale is like the eye of a horse – on the side of its head, looking at the world on that one side only and not in front of it, so the whale sees the two sides of itself as separate images, and has to integrate the two different side views of its world into one picture, much the way humans have to listen to different stories and the different realities of different people with different beliefs, and have to make a single coherent picture out of all the distortions and lies that we hear.

I wonder if it sees me, Malcolm thought. I wonder how a whale thinks, and what it thinks about. I wonder if it knows it is near death. I wonder what it knows and thinks about death at all. To the whale I am just an ant. A distraction, at best. A blade of grass. A dust mote glinting in the sunlight. Insignificant. The whale has a life that is so much bigger than mine.

“I’m with you, brother,” Malcolm said, out loud and to himself at once. “Or sister.”

Then he pulled out his cell phone and dialed 911.

Christine Larsen was an old white woman with arthritis of the hip which kept her from sleeping. She’d try the bed for a while at night, but the hip always woke her when she shifted position in sleep. She’d get up and take a little acetaminophen. Then she’d try the recliner in the living room, but she could never get comfortable there. Then she’d try to sit and read for a while at the kitchen table until she got drowsy. And then try the bed again. She’d sleep for a little while in fits and starts but her anxiety about whether she’d ever be able to sleep normally again, about whether she’d get enough sleep, always pushed sleep away and woke her before dawn.

That night she didn’t sleep at all. She heard the trucks on Route One headed to Westerly, the bells from the buoys in the harbor, even though the harbor was over a mile away. She heard the air conditioners of her neighbors droning into the night and even heard the compressors from the hospital in one direction, and the compressors in the buildings at URI in the other direction, chugging away. She heard each airplane in the sky headed to Europe and back. Each car door that opened or closed, anywhere in the blocks around her house. She heard the clang of the ramp on the Block Island Ferry all the way from Point Judith as the ramp dropped to make way for the waiting trucks and cars for its first trip of the morning. She heard the boats in Wakefield harbor knocking against their moorings, the strange hollow water-sound drifting on the ocean air. She thought she could hear the whoosh of blades of the big windmills out on Long Island Sound, but she understood that might be her imagination, that what she was hearing was more likely the ocean wind shifting through the trees around her house, in her little neighborhood not far from their little harbor. Distant sirens, now and again. Birds, once dawn approached, but far fewer bird calls and birdsongs than there used to be, the world being what the world had become.

She thought she heard a groan, the anguished grunt of defeat and dejection, in the darkness, and then what sounded almost like a sign of remorse and surrender, far away but still audible, in the dark, near the water. But then she doubted herself. Maybe it was a seal near the harbor, or the grunt of her neighbor’s rottweiler, left to sleep outside overnight, chained to its doghouse in the yard of the ex-cop who threatened the neighbors and was no better to his wives and children than he was to his dogs. No, it’s just my worn-out heart, Christine told herself. That’s how my heart feels. Abandoned and alone.

Nothing to be gained here, she thought. Let me go to the beach and watch the sunrise over Spain and Africa. I need a sweater, a kerchief, a folding chair and a book.

It was so early that there was only one other car in the parking lot. There was just the hint of light in the eastern sky, just blue grey at the horizon instead of night, though night itself had become diluted and had less grip on the earth. There was a waning quarter moon still visible, but the stars had faded.

Christine put the carry strap of the folding chair over her shoulder. She had on a red sweater and had wrapped a blue green kerchief over her hair and around her neck, and she carried a novel written by a dear friend that she promised to read, even though she doubted it would be very good.

She came over the crest of the dunes on the path from the parking lot to the sea and she saw the man, his silhouette against the lightening eastern sky, the shore birds skittering about and gulls drifting in the air or standing on the beach, their yellow bills tucked under a wing, facing the ocean and the incoming ocean wind. The man, a statue of strength against the wind, his windbreaker flapping in the breeze. What’s a man doing standing there alone like that, this early in the morning? she thought. She didn’t even see the whale, which just looked like a huge rock or a building, an inert black mass against the cresting and breaking waves and the slowly lightening sky.

But then the rock shuddered. It coughed. The great chest rose. And then collapsed, with a rush of liquid, air and steam that Christine could hear but not see.

She dropped the chair and the book in the sand.

He wasn’t young, the man standing there on the beach with his back to her, talking on his cell phone, but he was younger than she was, and he stood up straight.

“Are you…” Christine said.

“I just called 911,” the man said. “They said try calling animal control.”

“Animal control in South Kingston? No one in this town is up before 9,” the woman said. “Let’s do this. You call Animal Control. I’ll call DEM.”

“Done,” the man said.

DEM picked up on one ring. The operator was wide awake and sharp as a tack.

“I’m at Scarborough,” Christine said. There’s a whale on the beach. What should I do?’

“Do you know if the whale is alive?” the operator said.

“Looks alive to me” Christine said. “She’s breathing. Her eyes are open.”

“Any guess about what kind of whale it is we’re talking about?” the operator said. “I mean, a big whale or a smaller whale? A whale and not a dolphin, right? There have been lots of dolphin strandings lately over on the Cape.”

“No, a big whale. Huge. As big as a house. A big house.,” Christine said. “Please do something. She must be suffering. I don’t want her to die.”

“I don’t want her to die, either,” the operator said. “I’ll send someone over right away. Scarborough North or South?”

“North,” Christine said. Just south of the pavilion. You can’t miss her.”

“Hold the phone,” the operator said. “I’ll dispatch the Environmental Police right now. They should be there in a few minutes. Well, maybe twenty or thirty minutes.”

Christine looked up and saw the man standing and watching her, as if his call had ended.

“You were right,” he said. “Nobody’s home. I left a message.”

“DEM is sending the Environmental Police,” she said, her fingers over the microphone of her phone. “They’re dispatching someone now.”

“What good is that gonna do?” the man said. “What are they gonna do? Arrest the whale?”

Christine scowled. This man isn’t going to be of any help, she thought. I’m going to have to run this show. Like always.

The operator came back on the phone.

“They’re on their way. From Wakefield. Probably twenty minutes.”

“Ten minutes. I live in Wakefield. I know,“ the woman said.

“It’s 5:45 AM. The officer has to get out of bed, wash and get dressed. She’ll be there as soon as she can.”

“Do I know her?” Christine said. “I know half the town. I’ve been here forty years!”

The whale’s great chest rose again. And then collapsed again, with another rush of air and steam on the other side of the whale. It lifted the flipper that was in the air a few feet off its side. Then that flipper fell back again and lay limp along the whale’s great body.

“Oh my!” Christine said.

“Ma’am?” the operator said.

“Oh, the whale just moved and breathed out again.” Christine said. “So it is still alive. But hurry. It is taking one breath only every five minutes or so. Which can’t be enough. Please hurry.”

“The officer is on her way. Are you alone on the beach or are there other people with you?” the operator said.

“Oh, there is another person here. A man. But I haven’t had the honor of making his acquaintance.”

“Just stay away from that whale!” the operator said. “Tell that man and anyone who comes along to stay away. No touching or petting. No kicking or punching. No pictures in or near the whale’s mouth or tail. Marine mammals are wild creatures and unpredictable. Someone could get hurt.”

“Punching or kicking? Who would ever…” Christine said.

“That’s you. People are different. It’s hard to believe. But you don’t want to be in the way if that whale flips its tail, or somehow manages to roll over. That tail is more powerful than a locomotive. Stay out of the way. Keep everyone else out of the way. Please,” the operator said.

“Yes Ma’am!” Christine said,

“I’m going to hang up now and alert Mystic Aquarium, where the whale rescue team is. But you call back if things change,” the operator said.

“Does that mean I’m in charge until the officer comes?” Christine said.

“The whale is in charge. You stay away. And tell the other person there and everyone else to stay away as well,” the operator said. “Good-luck,” she said, and she rang off.

“I’m to tell you not to touch the whale,” Christine said to Malcolm. “I’m in charge until the environmental police arrive. They’re calling Mystic Aquarium! We’re not to touch the whale, and to make sure no one else touches the whale either.”

“I imagine we’ll have quite a crowd,” Malcolm said. “When word of this gets out. Thrill seekers. All sorts of people, who don’t know anything about the dignity of a great soul like this, near death and pondering the infinite.”

“So you aren’t going to kick or punch the whale?” Christine said.

“I’m not going to kick or punch the whale,” Malcolm said. “I’m wondering if we should be here at all. This is holy ground. Perhaps we are meant to be here, to protect this great being in her last moments, so she can rejoin the universe in peace.”

“Should I call Channel Ten?” Christine said.

“Don’t you dare,” Malcolm said. “People will figure this out on their own and the throngs will arrive, I promise you. But for now let’s think about the whale. I wish I knew how to make her more comfortable.”

“We haven’t met. I’m Christine,” Christine said. “From Wakefield.”

“Malcolm,” Malcolm said. “From Buttonwoods. That’s Warwick.”

The whale’s great chest rose one more time. And then collapsed. There was another rush of air and steam away from them. The whale’s tail lifted a few feet, and then fell back into the water where it had been resting, the incoming waves washing over it so the flukes rose and fell with each wave.

“That woman said the tail is powerful. And dangerous,” Christine said.

“You stay where she can see you,” Malcolm said. “I’m going to walk around the other side to look at the blowhole. But I want her to know that we are with her, that we are here protecting her, at least until those cops and the rest of the cavalry arrive.”

“Just keep your distance,” Christine said.

“You keep your eyes on the whale,” Malcolm said. “I’ll worry about me.”

Malcolm walked around the whale’s great mouth, and thought she moved her eye a little as he walked, tracking him for a few feet. Jonah, he thought, looking at the huge mouth, the size of a garage door. Or bigger. Only we have swallowed her, not the other way around. Ninevah. Jonah was supposed to go to Ninevah and get the king and all people there to repent. That’s not something we do, repentance. We don’t pause for one second to look around, to think about who we are and who we’ve become or think about what it would take for us to be one people, taking care of everybody, taking care of each other.

Malcolm took a few more steps, keeping his distance in fact. The damn thing is on its side. Its other eye was buried in the sand. That’s got to hurt. I wonder how it got so close to shore, as big as it is. High tide, Malcolm thought. Maybe it came in on the tide and will float out again when the tide goes out. I don’t know anything about the tides, other than what they say on the TV news for boaters. I reckon the tide is out. It will be back. What happens then?

Malcolm walked about ten feet and saw its blowholes, which looked like a human or an ape’s nose, two diamond shaped openings pointed backward, nostrils really, just upside down, from the perspective of humans. And each big enough to admit a big man’s arm. Or thigh, when you get right down to it.

What kind of a whale is this? Malcolm wondered. And what do I know about whales anyway? Just that they’re big. There was that whale Moby Dick, that white whale. That came after that captain guy, Ahab, when Ahab went after him. That ‘don’t you tread on me’ kind of whale. Kind of a white guy. Mean and unpredictable. Like Trump. But this whale isn’t like that. This whale is thinking. Dying. Maybe praying. I can feel it. I wonder if there are other whales offshore, waiting, hoping that this baby will get free and come back to them. I hope so. Or maybe they are having a death vigil, like a family standing around a hospital bed, holding the hand of the dying person who they love.

The whale’s great chest rose one more time. The great nostrils opened. And then collapsed. Then there was a burst of air and steam which burst toward Malcolm, so he stepped back but it spattered on him anyway. It was hot and it smelled, it stank really, of dead fish and flatulence, but Malcolm somehow didn’t mind. This is a great soul, he thought, and I am honored to be here now.

He walked to the water to wash his hands and face in the surf. The tide is coming in, he thought. I wonder if it will come in enough to lift the whale and set her free.

Then he walked around the whale’s head again. Her great eye tracked him again when he came back.

Three people stood on the dunes, looking down at them. The sky was lighter now. There were boats on the horizon. A plane that had taken off from Green Airport flew over, headed south, the first of the morning’s air traffic. They could hear trucks from Route One now, and the machinery noises from Point Judith as boats and trucks organized themselves. Those sounds traveled across the bay. A wind came up and made the flags over the pavilion snap as they fluttered in that wind.

It’s all downhill from here, Malcolm thought.

That old woman, Christine, had opened her beach chair. Her kerchief was orange and green. Her hair was white. And she was shivering.

The people on the dunes walked toward them, and Christine stood up.

“I’ve notified the authorities,” Christine said. “Keep your distance. Stand back from the whale. Help is on its way. I’m in charge here.”

A small boat appeared offshore. Then another. Then a man on a jet ski. Then five other people collected, one at a time, coming slowly from different directions, not believing their eyes and then recognizing that what they saw was in fact a whale stranded on the beach.

The great chest rose and fell one more time, and they all heard the rush of air, water and steam as the great chest fell. There was a groan, and a sigh from deep inside the great chest.

Then the great eye closed.

“Stand back,” Christine said. “I’m in charge here.”

Now there were thirty people, and no one was listening. People circled the whale. One or two reached out to touch her. A small child punched her.

“Go in beauty,” Malcolm said to himself. “Thank you for being alive. For showing yourself to me. For letting me be with you on this one moment, at this holy time, even for a little while, however insignificant I am.”

He closed his eyes and took a deep breath. He felt his pulse slow as he imagined himself in the water, diving to the ocean floor. He felt his arms and legs get cool as the blood shifted to his core and to his brain. His heart, though slower, seemed suffused with power in each of its beats.

An ultralight plane flew overhead. Then a drone began to circle above them, its red light flashing fifty or a hundred feet over the crowd and the body of the whale.

A woman in a green truck drove onto the beach and got out of the truck, wearing a green uniform.

None of this is real, Malcolm thought. No one else felt the beauty of the whale’s soul. Or heard it groan in its last moments. No one paused to listen.

We are wasting our lives, Malcolm thought.

Then he walked away.

Many thanks to Carol Levitt for proofreading, to Suzanne Vieira and to Brianna Benjamin as she goes off to law school for two amazing years of all-around help and support.

Thanks as well to an anonymous operator at RIDEM who answered my call one Sunday morning after one ring! And patiently walked me through what would happen if a whale beached in South Kingston.

Please click here to receive Michael Fine’s monthly short stories and his new series, What’s Crazy in Health Care. Please invite others to join.

Information about Michael’s books, stories, posts, talks and performances is available at www.MichaelFineMD.com Join us!

___

Read more short stories by Michael Fine, go here: https://rinewstoday.com/dr-michael-fine/

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor in Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.