Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Vinny Paz to be inducted TODAY into the International Boxing Hall of Fame – CES Boxing June 7, 2025

- In the News… quick recap of the week’s news (6.7.25) June 7, 2025

- Burn with Kearns: Strong without the spend: How scraps became strength tools – Kevin Kearns June 7, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 7, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 7, 2025

- How to advocate for threatened properties: The Heritage Alliance of Pawtucket June 7, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

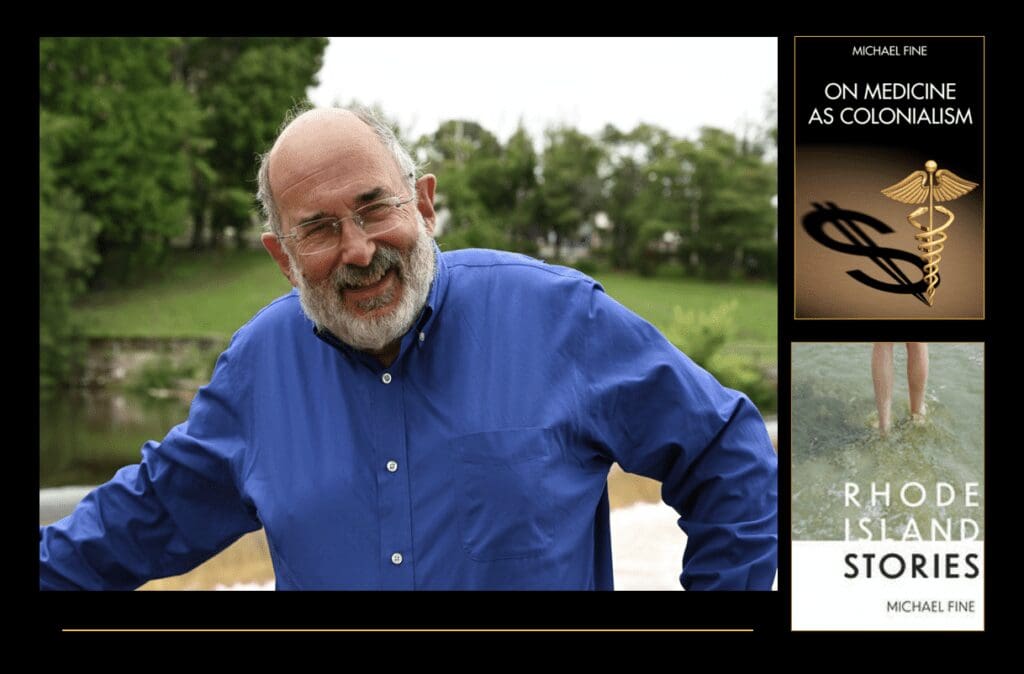

That was her brother who was naked – a short story by Michael Fine

By Michael Fine, contributing writer

Copyright © 2023 by Michael Fine

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

–

“That was her brother who was naked,” Edgar said. “Not her. She’d never do anything like that. Despite how she looks. Underneath her in-your-face appearance, the tats and the piercings and the half-shaved head, she’s a pretty careful soul. A shy person, at the end of the day. You wouldn’t think it.”

“No,” Bill said.” I never saw anybody more out there on stage, more provocative.”

“What you see is not necessarily what you get,” Edgar said. “You got to spend a little time with her. I sat down with her before one of her appearances. She’s the sweetest human. Calm, thoughtful, reflective. The whole nine yards.”

“Then why the outrageous stage presence?” Bill said. “The noise, the smoke, the blood…”

“It’s all part of her act,” Edgar said. “She’s just trying to get a rise out of you. Out of her audience. She’s trying to stir people up. People who are slumbering. Ask her. Talk to her. You’ll see.”

“I’ll leave the talking to you,” Bill said. “I’ve got lives to save. People to treat and street. The raw excitement of the healing arts. You know the drill.”

“That’s your drill, brother,” Edgar said. “The only life I ever save is my own. Once in a while. And only barely.”

“Amen to that,” Bill said. “The rest of us are pretty glad you save that life. Most of the time. Only barely. But not when you put Shulamit on stage.”

“A little blood and guts isn’t going to kill you. It makes you stronger. Man up. Or person up. Whatever,” Edgar said. “Might expand your horizons a little.”

“Leave the blood and guts to me, thank you very much,” Bill said. “Just make sure she doesn’t start cutting off body parts and throwing them at the audience. I’ve got plenty of work already. Too much work. Human beings are too bloody already, way too out there, way too crass and cruel for my taste. Slava Ukraini.”

“You think?” Edgar said. “But we got to look at ourselves. See ourselves for who we are. Then maybe we can change. Maybe. Probably not. Remember change always favors the change agent. Art is a mirror, looking at us as we are, not trying to fix anything. Cause we ain’t broken.”

–

They’d had a fake winter. It never really got cold and didn’t snow enough to count, and then they had two weeks of bright days and nights above freezing in mid-March, enough to bring the forsythia into bloom, get the daffodils to open and let the trees starting to bud. The branches that had been brown and gray and dead-looking became red and purple as if they had blood coursing through veins, as if bushes and trees could experience lust and they were engorged and ready to bust out. Then a cold snap blew in from Canada and cut that false spring off at the knees. The flowers turned to ice and fell from the stems. The wind got so cold you didn’t want to get out of bed in the morning and got you to invent excuses to work virtually so you didn’t have to go out in the cold.

The days were longer, true, but the sky stayed dark, the wind strong, and it always looked like rain. Rain or sleet fell intermittently, a thousand cuts on your skin if you walked outside, a spattering or crusting on your car’s windshield that kept the windshield fogged, if and when you chose to drive.

Bill walked anyway, his coat collar turned up, wearing a fake fur Russian hat and a red and purple scarf that he’d bought in Venice. Got to get out, he told himself. Got to move. So, he walked to Seven Stars on Broadway in the wind and the rain, the wind gusts pushing him back as he tried to walk forward, the splattering rain wetting his forehead and glasses so he could barely see.

It was warm in Seven Stars, thank God, and the place was full of people, the warm fetid smell of fresh brewed coffee, the clink of coffee cups on their saucers, the rat-a-tat-tat sound of chairs being dragged across the floor, the din of voices, of chatter — a warm place on a cold and dark day. Bill’s glasses fogged as soon as he came through the door. He couldn’t see anything until he took his glasses off and wiped them clean.

There she was, right in front of him in line.

What was her name? Shulamit, the woman he had asked Edgar about, who did that outrageous performance that insulted Bill’s sense of propriety and decency every time she took the stage. Buzz-cut on half her head. Pink and purple hair otherwise. Tattoos everywhere, green and purple tattoos that swirled around her neck like snakes.

“Hey,” she said when she turned to look around the room and saw Bill looking at her.

“Hey,” Bill said back.

“Do I know you?” Shulamit said.

“Not entirely. I mean, not really,” Bill said. “We’ve never been properly introduced, if that’s what you mean. But I know who you are.”

“And I know who you are, too,” Shulamit said.

“Not,” Bill said. “I ain’t anybody.”

“Give me a break,” Shulamit said. “No need for that false modesty bullshit. Everybody knows who you are. Everybody in Providence, at least. In Rhode Island. Everybody who’s anybody. The man who wrestled Brown to the ground. The man who made those assholes on the hill behave like human beings again. Who made them pay their fair share. And stop acting like gods and goddesses, sitting up there on Mount Olympus. Who wrestled with Zeus and beat him. Who outran Apollo. Who flattened Ares with a right hook. That guy.”

“That’s silly,” Bill said. “We all did that together. One or two little editorials. For a newspaper that died years ago, chewed up and spit out by the corporate woodchipper, and is now not even a ghost of what it was. Anyway, Brown hasn’t been wrestled to the ground, not by a long shot. Those guys just changed their MO. They still call the shots. They just do a better job hiding what they do and how they do it. They know how the game is played and they know how to get what they want. The old Speakers, they still run the lobbying in the statehouse. The unions still control politics here by turning their people out to vote in primaries, and the good old boys still run the unions. So, nothing changed. And nothing will. Despite all the sturm and drang, all the hubbub. But I had no idea you knew anything about mythology.”

“There’s lots you don’t know,” Shulamit said.

“Apparently,” Bill said.

–

Bill didn’t think their thing would last two weeks. Thing. It was just a thing. There just wasn’t a better word to describe it. An exploration. An opportunity. A little moment in time. In a time of situation-ships, not relationships. In the time of global warming, war in Ukraine, Trumpian nonsense, US democracy falling apart at its seams, inflation, banks in constant chaos, China on the rise, dictators replacing democracies around the world, the tail of the pandemic etcetera, etcetera, and so forth. When nothing could be counted on, when there are no rules and no consequences and nothing and nobody is who they seem to be. And nothing matters. In a time of distraction, not passion or meaning.

Bill didn’t think Shulamit meant anything to him. He couldn’t understand why Shulamit was interested in him, except as a passing fancy, as entertainment, a distraction from what was really bothering her about the state, the nation, the world, and the universe. In a time when people walk their dogs, paste pictures of their dogs on Facebook and Instagram, get their dogs massages and CT scans and chemotherapy, and only dogs seem to matter. Not people anymore. Chat GPT. In this time when humans and relationships have almost ceased to exist.

–

But she did mean something to him, and even more surprising, he seemed to mean something to her.

She would look into his eyes when she talked to him. Deep into his eyes, connecting and probing at once. Who was he? Could she trust him? Could she believe him? Did she think what he was saying was true? Why did he think that? How did he know? Of what use was thinking that way? Why was thinking any good, after all, if it brought us to this absurd place in the cosmos, in the Geist? We had been better off as hunter-gatherers. Why had we left reason, connection, and humanity in the dust?

And Bill, for his part, learned from her every minute he was with her. She told him his facts were full of assumptions, riddled with bias and bad faith. You don’t have to live in your head, she said. You can live in the moment. Dreams and guesses count. Hallucination and hope matters. Other people’s ideas, and even more, other people’s rules don’t count. They are to be ignored at least and shattered at best. Other people’s rules serve them, not us, not our deep connections to the story of creation, not to the earth or its wisdom and not our deep connections to one another. Other people’s ideas never connect us to the truth.

–

Then Bill learned Shulamit had a kid.

They were walking in the Zoo. It was a Tuesday afternoon. The weather had warmed again. The sun was strong at midday now, the days longer than the nights. The daffodils and forsythia were starting to bloom again, brilliant yellows dappled on spindly branches, spread out where lawns would soon be. There was a hint of green in the grass which had been only brown and tan.

The Zoo was empty, a perfect time to study these different life forms without interruption, and to experience their own differences and similarities. You could smell the sea air, blowing in from the Port of Providence, and just a hint of zoo smell, a dank undercurrent of old hay and fresh manure, that the breeze didn’t hide, that was refreshing, in its way, for its honesty. It was a zoo. Not a flower garden.

They stopped in front of the elephant compound. There were three elephants there, all females. They stood basking in the sun in the middle of the compound, half asleep.

“No males,” Shulamit said.

“Thank God,” Bill said. “No males, no war. Imagine what a loose bull elephant could do to the city of Providence?”

“Improve it?” Shulamit said. “My kid says they should knock Providence down and start over again. Starting with Nathanael Greene. Her middle school.”

“What kid?” Bill said.

“My kid. Susquehanna. She’s eleven.”

“You didn’t tell me you had a kid,” Bill said.

“You didn’t ask.”

Bill turned. There was some kind of exotic pig in a little compound behind him, snoring as it slept in the sunshine.

“How come I haven’t met this kid?” Bill said.

“She’s with her father,” Shulamit said. “That’s how we do it. Two weeks on, two weeks off.

“Got it,” Bill said.

“That pig looks something like an elephant,” Shulamit said. “Only a lot smaller. And without a trunk or those ears.”

“If a duck had spots and ran fast it would be a cheetah,” Bill said.

–

It had been a stretch, being with Shulamit. The tats and the piercing and the half-shaved head. She wasn’t anybody he’d ever thought of being with, in his mind’s eye, in his heart. He hated what she did on stage, who she became. She was Israeli. Israelis are crazy people, every single one. They never get over what they have to do to survive and who they have to do it to, even though they are all pretty proud of doing unto others before those others do it unto you. They have nightmares and pretend they are dreams.

A kid.

They were standing near a little food stand, which was closed. The head of a giraffe appeared through the trees behind them. They had already seen the giraffes. Giraffes had sensitive eyes with long eyelashes, long thin nostrils, little prongs where horns should be and ears that point backward, that stand up when the giraffe looks at you.

“I’m headed to the zebras and wildebeests,” Shulamit said.

–

You shouldn’t bring kids into this world, Bill thought. It’s way too crazy. Let the human species die out. Shulamit should know that. You don’t have kids now. It’s too late. We’ve already destroyed the earth and are just awful to one another. Wasn’t that the point of Shulamit’s act? To say what no one wanted to say? To get people to own the truth? Now Bill knew that Shulamit was just like everyone else, despite how she looked. She was not what she appeared.

“You’d like my kid,” Shulamit said. “She has a mind of her own. She’s not like me. She wears dresses.”

“Huh,” said Bill. “Who knew?”

Shulamit started walking up the black asphalt path.

–

“Coming?” Shulamit said.

“You go ahead,” Bill said. “I’ll be along. I want to spend a couple of minutes, hanging out with the cheetahs.”

–

Bill watched Shulamit walk to the zebras and the wildebeests.

He took a few steps toward the cheetahs.

Then he turned and hurried away.

–

Thanks to Catherine Procaccini for proofreading And The Brianna Benjamin for all around help and support.

All of Michael Fine’s stories and books are available on MichaelFineMD.com or by clicking here.

___

Michael Fine, MD is currently Health Policy Advisor in Central Falls, Rhode Island and Senior Population Health and Clinical Services Officer at Blackstone Valley Health Care, Inc. He is facilitating a partnership between the City and Blackstone to create the Central Falls Neighborhood Health Station, the US first attempt to build a population based primary care and public health collaboration that serves the entire population of a place.

He has also recently been named Health Liaison to the City of Pawtucket. Dr. Fine served in the Cabinet of Governor Lincoln Chafee as Director of the Rhode Island Department of Health from February of 2011 until March of 2015, overseeing a broad range of public health programs and services, overseeing 450 public health professionals and managing a budget of $110 million a year.

Dr. Fine’s career as both a family physician and manager in the field of healthcare has been devoted to healthcare reform and the care of under-served populations. Before his confirmation as Director of Health, Dr. Fine was the Medical Program Director at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections, overseeing a healthcare unit servicing nearly 20,000 people a year, with a staff of over 85 physicians, psychiatrists, mental health workers, nurses, and other health professionals.

He was a founder and Managing Director of HealthAccessRI, the nation’s first statewide organization making prepaid, reduced fee-for-service primary care available to people without employer-provided health insurance. Dr. Fine practiced for 16 years in urban Pawtucket, Rhode Island and rural Scituate, Rhode Island. He is the former Physician Operating Officer of Hillside Avenue Family and Community Medicine, the largest family practice in Rhode Island, and the former Physician-in-Chief of the Rhode Island and Miriam Hospitals’ Departments of Family and Community Medicine. He was co-chair of the Allied Advocacy Group for Integrated Primary Care.

He convened and facilitated the Primary Care Leadership Council, a statewide organization that represented 75 percent of Rhode Island’s primary care physicians and practices. He currently serves on the Boards of Crossroads Rhode Island, the state’s largest service organization for the homeless, the Lown Institute, the George Wiley Center, and RICARES. Dr. Fine founded the Scituate Health Alliance, a community-based, population-focused non-profit organization, which made Scituate the first community in the United States to provide primary medical and dental care to all town residents.

Dr. Fine is a past President of the Rhode Island Academy of Family Physicians and was an Open Society Institute/George Soros Fellow in Medicine as a Profession from 2000 to2002. He has served on a number of legislative committees for the Rhode Island General Assembly, has chaired the Primary Care Advisory Committee for the Rhode Island Department of Health, and sat on both the Urban Family Medicine Task Force of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the National Advisory Council to the National Health Services Corps.