Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Writer Herb Weiss’ 45 years of Advocacy on Aging now Archived at Rhode Island College Library Special Collection June 23, 2025

- Providence Biopharma, Ocean Biomedical, Notified of Termination of License Agreements with Brown University, RI Hospital June 23, 2025

- Networking Pick of the Week: Early Birds at the East Bay Chamber, Warren, RI June 23, 2025

- Business Monday: Dealing with Black and White Thinking – Mary T. O’Sullivan June 23, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 23, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 23, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Schools near highways: Open windows let toxic pollutants in – Richard Asinof

The dilemma posed by opening windows at schools is that in efforts to reduce the possible transmission of the coronavirus, it is increasing the flow of toxic pollutants from highway exhaust into the classroom

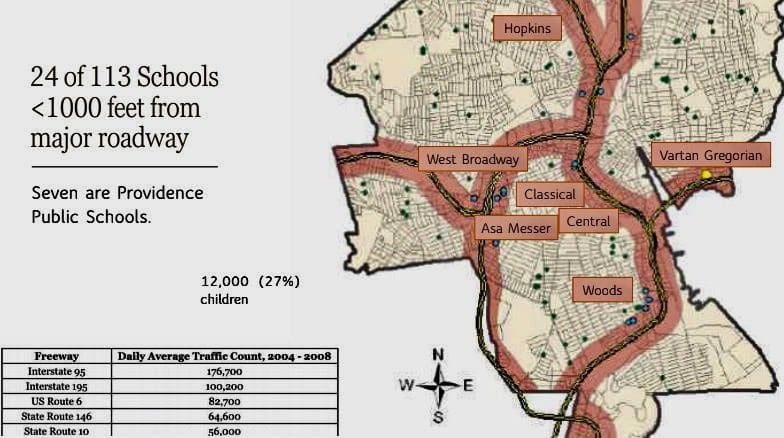

Photo: A map details the proximity of schools that are less than 1,000 feet from major roadways in Providence.

by Richard Asinof, ConvergenceRI, contributing writer

When Dr. Elizabeth Goldberg, MD, an emergency medicine physician, sent in her op-ed to ConvergenceRI, it was the beginning of a conversation – one, like many conversations and convergences that I have begun during the last eight years, starts with a series of questions.

Because I had done some previous reporting on the air quality issues at the Vartan Gregorian School in Fox Point, adjacent to I-195, I wanted to dig a bit deeper and engage with Goldberg on the topics.

[For transparency purposes, in July of 2019, I had bumped into a parent whose child went to Vartan Gregorian on the evening that wheels of bureaucracy had voted to approve the state’s takeover of the Providence Public School Department, outside the downtown URI facility where the vote had taken place, and he told me about how parents and teachers had installed air filters at the school, concerns about air pollution. [See link below to ConvergenceRI, “What is the remedy for sick buildings?”]

That story had been preceded by two others on education: one, an in-depth look at the performance by newly appointed R.I. Education Commissioner Angelica Infante-Green; the second, a story by teacher Betsy Taylor, about the terrible conditions at Hope High School where she taught, a story that garnered more than 15,000 views in less than two months. [See links below to ConvergenceRI stories, “A teacher speaks her mind,” and “The importance of being earnest about education in RI.”]

I also re-published a story written by Grace Kelly at ecoRI News in November of 2019. [See link below to ConvergenceRI story, “In goes the bad air.”]

So, I sent off a number of questions to Goldberg. Not surprisingly, Goldberg was extremely well-versed about what was happening on the ground in Providence schools. Here are questions and answers:

ConvergenceRI: In previous reporting by ConvergenceRI, I became aware that the Vartan Gregorian School had installed air filters. Do you know what the status is of these filter systems? Are they still in operation?

GOLDBERG: Yes, PPSD aimed to get higher quality filters [MERV 11 filters that can help filter out infections and particulate matter], but not all HVAC systems are compatible with high MERV-rated filters, because these filters can cause a large drop in system pressure.

A recent bid for HVAC filters and air purifier filters that the Providence Public School District posted suggests they are trying to upgrade and keep the filters maintained, but [the filters] are of varying quality, likely because the school buildings have really old HVAC systems that can’t support higher quality filters.

The Providence Public School District did install air purifiers in the classrooms once windows could no longer be opened, [in response to the COVID-19 pandemic]. A problem with pollution is that these older schools rely on natural/passive ventilation where they open windows.

But the EPA recommends central HVAC for near-highway school because passive ventilation just let’s the pollution in.

Due to coronavirus, teachers have been encouraged to open windows, which is fine if you’re out in the country. But Providence has these major roadways running right through the center of the city and right by all the schools, so this is a poor solution for these kids.

The dilemma, of course, is this: Do you let the pollution in, or do you let the kids have higher risk of coronavirus transmission?

The public, in my opinion, gets that ventilation is good and opening windows is good, but it’s hard [for them] to understand that this lets particulate matter in from vehicular exhaust.

ConvergenceRI: Once again, in previous reporting by ConvergenceRI, there was a study done in California related to student performance, following the installation of air filters following a serious gas leak. A study found that those students’ performance improved on a level of lowered-class sizes. Were you aware of that study?

GOLDBERG: Yes, I know of that study and agree that these air purifiers may have an effect on school performance, if they are maintained. [Goldberg gave a presentation to the Providence Public School District.]

To my knowledge, we do not have the carbon filters that the air purifiers in California had that are especially useful for gas leaks, so gaseous pollution may not be filtered out as much as particulate matter with the schools’ current set-up.

The conversation/convergence continues

After reading and agreeing to publish the op-ed by Goldberg, there were a number of follow-up questions that ConvergenceRI felt were important to ask.

ConvergenceRI: Where should the money come from to pay for these improvements?

GOLDBERG: Improving our aged school buildings will be costly, in addition to paying for annual monitoring programs. Really, there are dilapidated schools across the country and a strong case can be made that Congress should dedicate funds to school infrastructure, particularly for critical building systems like ventilation and air conditioning.

Although public schools are the second-largest facilities sector, the federal government provides almost no money for school operations. Some of the funding will need to come from the state, for instance, to fund additional staff at the R.I. Department of Health and the R.I. Department of Environmental Management to do the monitoring and assess mitigation measures.

The Coronavirus Relief Bill [now pending in Congress] may be a temporary source for this funding. Some of the funding can come from school bonds targeted to improving our aging school buildings. Municipalities will also need support these efforts, as repairs and upgrades to buildings are long overdue.

The kids need more than new filters and air purifiers in the classrooms; they need upgrades to the building envelope, repair of leaky windows and unit ventilators, and ideally central HVAC.

Natural or “passive ventilation,” where you open the windows to let air in, are not recommended by the EPA for schools near highways.

ConvergenceRI: Is there a need to better monitor what is actually in the air in classrooms in Providence?

GOLDBERG: Absolutely! We don’t know the extent of the problem. In 2011 a group of scientists [Selix and Hastings] from Brown University measured the air quality in and outside of one of our Providence schools, and they found that levels of nitrogen dioxide over 24 hours outside the school were seven times the EPA’s yearly average for Providence and exceeded the NAAQS recommendations for air quality.

In their conclusions, they stated “Extensive repeated measurements across the city are necessary to fully quantify the problem. To address this problem seriously, long-term testing in various schools in the city over different seasons and weather conditions is suggested.”

Nitrogen dioxide can cause irritation of the eyes, nose, and throat, breathing problems, and impacts the liver, spleen, and blood. To my knowledge there hasn’t been air quality testing of outdoor pollutants impacting school children in Providence since those academic efforts in 2011. I do believe the district does testing for mold and other more easily measured substances.

ConvergenceRI: How much of this issue is related to climate justice, in how poorer, more diverse neighborhoods are more likely to be the victims of air pollution burdens?

GOLDBERG: People living in low income housing in Providence have the highest rates of asthma in the state. Black children in Rhode Island are four times more likely to attend near highway schools in Rhode Island [Welleniu, 2014].

Kids who [live] downwind of highways experience decreases in test scores, more behavior issues, and more absences, relative to when they attended schools upwind of highways.

The problem here is not with the kids, the problem is their environment. Air quality in schools and low-income housing is a major climate justice issue,and efforts need to focus on creating safe environments for all Rhode Islanders.

ConvergenceRI: Can this process be used as a way to bring parents, teachers, and administrators together on an initiative that finds common ground around improving students’ health?

GOLDBERG: Most definitely! We all benefit from enhancing the safety and quality of our public spaces. Everyone would like less respiratory infections and less congested roadways. This problem is about far more than aged school buildings.

We have major roadways that cut through our city and create vehicular exhaust that affects most of us in our homes or at work.

Interstate agreements like the Transportation Climate Initiative that incentivize cleaner transit and provide funding to climate justice issues are a good start.

We have industries in the center of our city that should contribute more to the wellbeing of their neighbors by reducing their carbon footprint.

Fines collected from industrial mishaps should benefit low-income communities and school children that are impacted most by the pollution.

In general, we need more environmental enforcement to protect vulnerable communities and “sensitive receptors” like children, whose lungs and brains are still developing.

One initiative that could help us prepare for the “green economy”is Climate Jobs Rhode Island. I’d also like to see more investment in electric school buses. The current diesel school buses are a major source of air pollution that [harm] our entire community.

ConvergenceRI: What questions haven’t I asked, should I have asked, that you would like to talk about?

GOLDBERG: What can private citizens do to support clean air? Join the public conversation surrounding health and pollution. Testify when Sen. Gayle Goldin’s Air Quality bill is introduced about how your kids’ or your own lung conditions related to pollution and how they have impacted your life. Share your concerns regarding pollution, traffic congestion, and climate change with your legislators.

To read the article in full: http://newsletter.convergenceri.com/stories/children-and-teachers-first,6391

_____

Richard Asinof is the founder and editor of ConvergenceRI, an online subscription newsletter offering news and analysis at the convergence of health, science, technology and innovation in Rhode Island.