Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Writer Herb Weiss’ 45 years of Advocacy on Aging now Archived at Rhode Island College Library Special Collection June 23, 2025

- Providence Biopharma, Ocean Biomedical, Notified of Termination of License Agreements with Brown University, RI Hospital June 23, 2025

- Networking Pick of the Week: Early Birds at the East Bay Chamber, Warren, RI June 23, 2025

- Business Monday: Dealing with Black and White Thinking – Mary T. O’Sullivan June 23, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 23, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 23, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

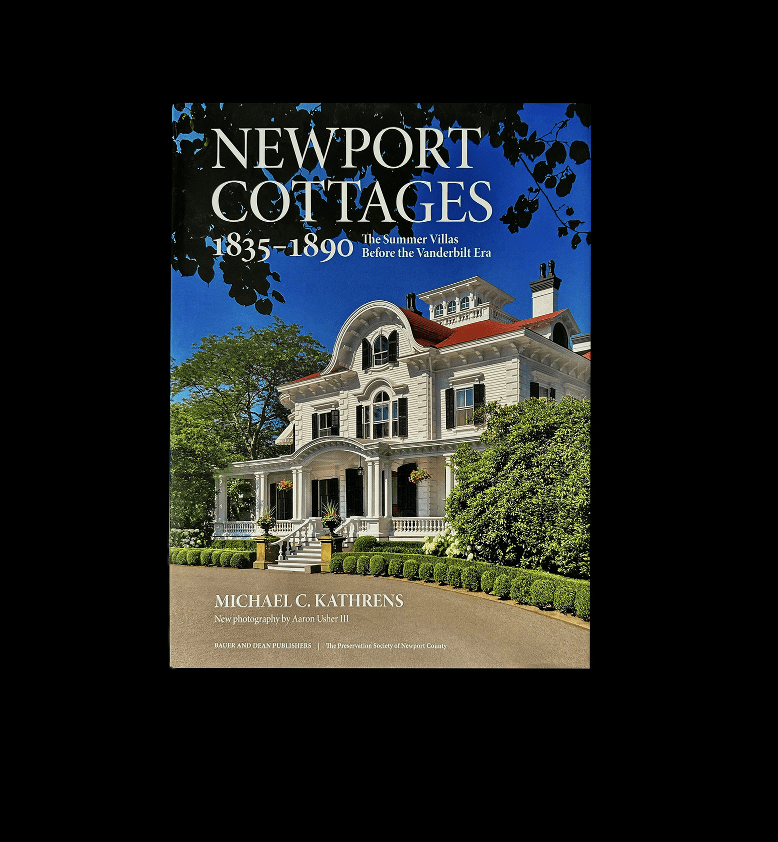

Review of Newport Cottages, by Michael C. Kathrens – David Brussat

Cover illustration of Cannon Hill (ca. 1850), on the west side of Bellevue Avenue, built by a family from Boston. Photo by Aaron Usher III Photography

This excellent volume is the second describing the splendid dwellings of the summer colony of the City by the Sea, by architectural historian Michael C. Kathrens. It is subtitled “1835-1885: The Summer Villas Before the Vanderbilt Era.” His first volume describes the even more ambitious “cottages” inspired by European classical styles, and is titled Newport Villas: 1885-1935. The second volume, published by Bauer & Dean of New York, with a Foreword by Trudy Coxe of the Preservation Society of Newport County, is illustrated by 176 color photographs by Aaron Usher III, with 336 black-and-white photos, mostly historical.

The word cottages is something of a misnomer. The earliest of these, built even before 1835, were indeed more like mansions than cottages, albeit smaller in scale than those of the Vanderbilt Era. My impression is that Newport’s summer visitors continued to use the word cottage for its charming irony, as set against the word’s conventional quaintly cozy appeal. There may have been a classist element lurking in this usage. Even the early elite summer colony’s cottages were hardly quaint, let alone cozy – though it is likely that many small summer houses erected by the non-elite did, in fact, qualify as cottages in the normal meaning. But they were never examined historically, and are probably almost all gone by now. Maybe this is not strictly true; I invite the author to disagree in the comments below.

It is often noted that the elite summer colony drew families from the American South, which by 1835 was headed for war with the abolitionist North. Certainly Michael Kathrens takes due note of this anomoly. He writes in his introduction: “Of the twelve private cottages known to be standing in 1852, southern families owned eight… In fact, more seasonal abodes were constructed in Newport between 1865 and 1885 than in the following decades, during what became known as the European Revival period that lasted almost half a century.” (Of course, many of these were larger and occupied vastly greater acreage.)

South Carolina plantation owner John Rutledge wrote in 1801 to ask a friend to push his agent harder:

I will embark in the first good vessel that offers for Newport. When I heard from Mr. Gibbs last[,] he had not obtained a house for me. I wish you would see him, and, if he has not got one, you will greatly oblige by uniting with him in endeavoring to get a house for me. If I cannot get one I shall be obliged to pass the summer at Boston, and I would not like that …”

In the 1840s, “Alfred Smith, an ambitious,self-made developer, had confidence that Newport’s summer colony lay in the direction of individual cottages.

He formulated a plan to convert the open farmland and pastures east and south of town into commodious ocean-view lots that would be accessed by a network of broad avenues. Although there would be many investors involved in this pursuit, only Smith comprehensively grasped the possibilities and carried the plan through to its successful completion.

Born in 1809 on a small farm in neighboring Middletown, Rhode Island, Smith became a cloth cutter in Providence before moving to New York City. There he worked for many years as a tailor in the firm of Wheeler & Co. By the time he was thirty, Smith had saved $20,000, with which he returned to Newport in 1844 to begin a career in real estate.

The following year, Smith formed a syndicate to buy three hundred acres north of Bath Road – now Memorial Boulevard … . He went on to push Bellevue Avenue south to Rough Point, while to the east he created Ochre Point Avenue. … To add cachet, Smith designated each new roadway an “avenue” instead of using a more common-sounding “street” or “road” appellation. … The last leg of Smith’s plan was the creation of Ocean Drive[.]

One wonders whether such a career would be possible in the United States of today.

Multiply the items cited above by a dozen, or a score, and you have some idea of the scope of material covered by Newport Cottages.

That suggests my only problem with this voluminous volume, which is also its greatest blessing: There is too much of it. The book’s 400 pages won’t be carried around easily by sightseers to Newport’s summer habitations. And yet the flow of detail from page to page – of a cottage’s lengthy architectural pedigree in addition to that of its ownership history – seems to invite examination during a walking tour of the neighborhoods described. Don’t lug it along. Lay the book out on a coffee table at home after returning from a tour and see if you can match your own photos or your memories to the photos in the book. Come to think of it, a book any smaller, with much of its text and photos edited out, would clearly be a lesser tour de force.

So buy it for Christmas before it actually shrinks, as everything else seems to do.

___

To read other articles by David Brussat: https://rinewstoday.com/david-brussat-contributing-writer/

My freelance writing and editing on architecture and others addresses issues of design and culture locally and globally. I am a member of the board of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which bestowed an Arthur Ross Award on me in 2002. I work from Providence, R.I., where I live with my wife Victoria, my son Billy and our cat, Gato. If you would like to employ my writing and editing to improve your work, please email me at my consultancy, dbrussat@gmail.com, or call (401) 351-0451.