Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Real Estate in RI: Seaside waterfront communities are all the rage. Who’s buying – Emilio DiSpirito June 6, 2025

- Outdoors in RI: 2A votes, Charter Yachts, active summer programs, garden tours, aquatic weeds… June 6, 2025

- All About Home Care, with two Rhode Island locations, closing after 22 years in business June 6, 2025

- GriefSPEAK: Angel wings with footprints – Mari Nardolillo Dias June 6, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 6, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 6, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Reverse Landscape of Despair, with David Brussat

How architecture can create a gentling of mind.

Reverse Landscape of Despair

By David Brussat, Architecture Here and There

Understandably, an overlooked part of the debate about architecture is the ease of moving back to tradition in building cities and towns.

My blog on Friday, Modern Architecture is Killing Us quoted extensively from James Howard Kunstler’s essay “The Landscape of Despair” in the Daily Caller. It ended with a passage from Sir Roger Scruton, which I introduced by noting that he “describes what societies across the globe have abandoned” – traditional cities and towns – “which we can have back anytime we want, basically just by asking. But first we must realize that it is what we want.”

Just by asking? Yes! And realizing what we want? Yes! Let me explain.

First, reading Kunstler on the way we live in ugly cities and towns, it must be clear that we want something else, and why not something that works and is beautiful, too? It is Scruton’s belief (and Kunstler’s too, I’m sure) that the traditionally designed buildings, cities and towns that we have largely lost had a gentling effect on the human condition. People are happier and behave in a more civilized manner when their surroundings do not cause feelings of abandonment and despair. History seems to demonstrate that. Despite all our technological advances over the past half century, life has grown more coarse and less civilized at all levels. However, we might explain this, the ugliness of our built environment, with the individual and collective anomie it fosters, must surely contribute. Kunstler’s description suggests that the contribution is devastating.

So yes, I think it is fair to say that what we want is to have back what we abandoned, that is, the generally attractive traditional settings in which we once lived our lives.

The harder question is can we get it back just by asking?

That overstates the case, but I believe we can. The photo atop this post is of a row of townhouses in Seaside, Fla., a beach community designed under the New Urbanist umbrella – which is (or maybe was) a modern effort to revive the beauty and practicality of pre-World War II communities. I chose it because it is remarkably charming, but its charm is, as a practical matter, within reach. There are many other models of gracious living, such as almost the entirety of Paris, that today are available only to the wealthy – not because they are unfeasible at lower income levels but because so few are built or remain from older times. A historic district is merely a neighborhood built before World War II. Their prices are bid upward astronomically. To build beautiful is not unnaturally expensive, but the industry encompassing development, design and construction has evolved so as to favor the quick buck for shareholders at the expense of, rather than to provide for, the needs of people who use and occupy the “product.”

So, yeah, let’s “just ask” industry leaders to do the right thing!

Seriously, this requires finding a key, a tipping point that will shift the market paradigm. That has been done in history many times before, from the horse and buggy to the cell phone. In U.S. cities and towns, anxiety over modern architecture and urban renewal was easily leveraged into a mass movement – historic preservation. It will not be easy, merely easier (a lot easier) than solving most of the problems that face society today.

Making peace instead of war, avoiding climate catastrophe, feeding the hungry, reducing disparities of income and class, educating the young, ending mass shootings and inner-city crime – these challenges will not be resolved until society agrees how. In architecture and planning, agreement that beauty is preferable to ugliness already exists to a degree that, in a democratic society, should enable a paradigm shift. How to incorporate beauty into our built environment is already well known and widely desired. The majority who equate traditional settings with beauty and modernist settings with ugliness is sizable enough that action can be mobilized. But most people tune out their built environment because it is so bad and seems so hard to do anything about – so hopeless. Just imagining a reversal of our landscape of despair is hard enough. Still, we need only realize that we have the power to bring real change in our built environment.

How to activate that realization is the next big question. Trying to improve education in architecture and planning is vital, but could take decades without a timely intervention from outside academe. Such an intervention, pushing us to a tipping point, might well take the form of a shift in the approach of architects and planners to, say, climate change, going from “gizmo green” to the design of houses that harness nature to regulate indoor climate (windows that open and close, for example), as we did for centuries before the thermostat age. Or it could be that a major publicity campaign to rebuild the original Pennsylvania Station might spark a public reaction that pushes New York politics to a tipping point, which could generate new traditional projects nationwide and beyond. Or it might be a discovery that public participation in the local development process can be fun. Direct action to rattle developers at design hearings. Abbie Hoffman might come out of retirement (or the grave) to write another book, Steal This Hearing!

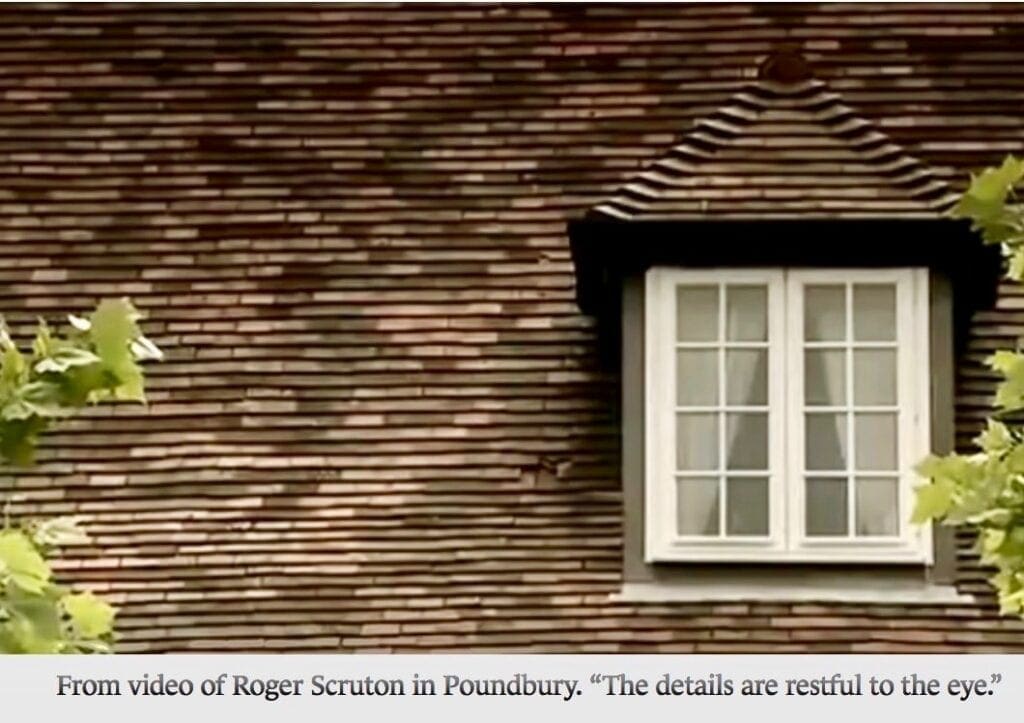

Or maybe something else. There are many possibilities. That our landscapes of despair must change for the health and well-being of society, and the planet, is clear enough. Here is a very brief video by Roger Scruton on Poundbury, a new town built with traditional techniques. Scruton explains the simple desires that Poundbury satisfies. “The details are restful to the eye,” he says. Let us continue to discuss suggestions toward that end.

David Brussat

This blog was begun in 2009 as a feature of the Providence Journal, where I was on the editorial board and wrote a weekly column of architecture criticism for three decades. Architecture Here and There fights the style wars for classical architecture and against modern architecture, no holds barred. History Press asked me to write and in August 2017 published my first book, “Lost Providence.” I am now writing my second book. My freelance writing on architecture and other topics addresses issues of design and culture locally and globally. I am a member of the board of the New England chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which bestowed an Arthur Ross Award on me in 2002. I work from Providence, R.I., where I live with my wife Victoria, my son Billy and our cat Gato. If you would like to employ my writing and editing to improve your work, please email me at my consultancy, dbrussat@gmail.com, or call (401) 351-0457. Testimonial: “Your work is so wonderful – you now enter my mind and write what I would have written.” – Nikos Salingaros, mathematician at the University of Texas, architectural theorist and author of many books.