Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Bed Bug Awareness: At home, hotel rooms, dorms, vacation rentals, only 29% can identify a bed bug June 8, 2025

- A crack in the foundation – Michael Morse June 8, 2025

- Ask Chef Walter: Ultra processed foods – Chef Walter Potenza June 8, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 9, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 8, 2025

- Vinny Paz to be inducted TODAY into the International Boxing Hall of Fame – CES Boxing June 7, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

Remembering Dr. Paul Farmer – Richard Asinof

by Richard Asinof, ConvergenceRI.com – contributing writer on health

An antidote to despair

Dr. Paul Farmer offered insights about what he has learned from his efforts to build a public health infrastructure in the clinical deserts of Haiti, Rwanda, Sierra Leone and now Liberia

Editor’s Note: Dr. Paul Farmer died on Monday, Feb. 21, in Rwanda, at age 62, in his sleep, from an apparent heart ailment. ConvergenceRI is republishing the interview with Dr. Farmer, conducted in 2017, and published in January of 2018, during a time today when there is a great need for an antidote to despair.

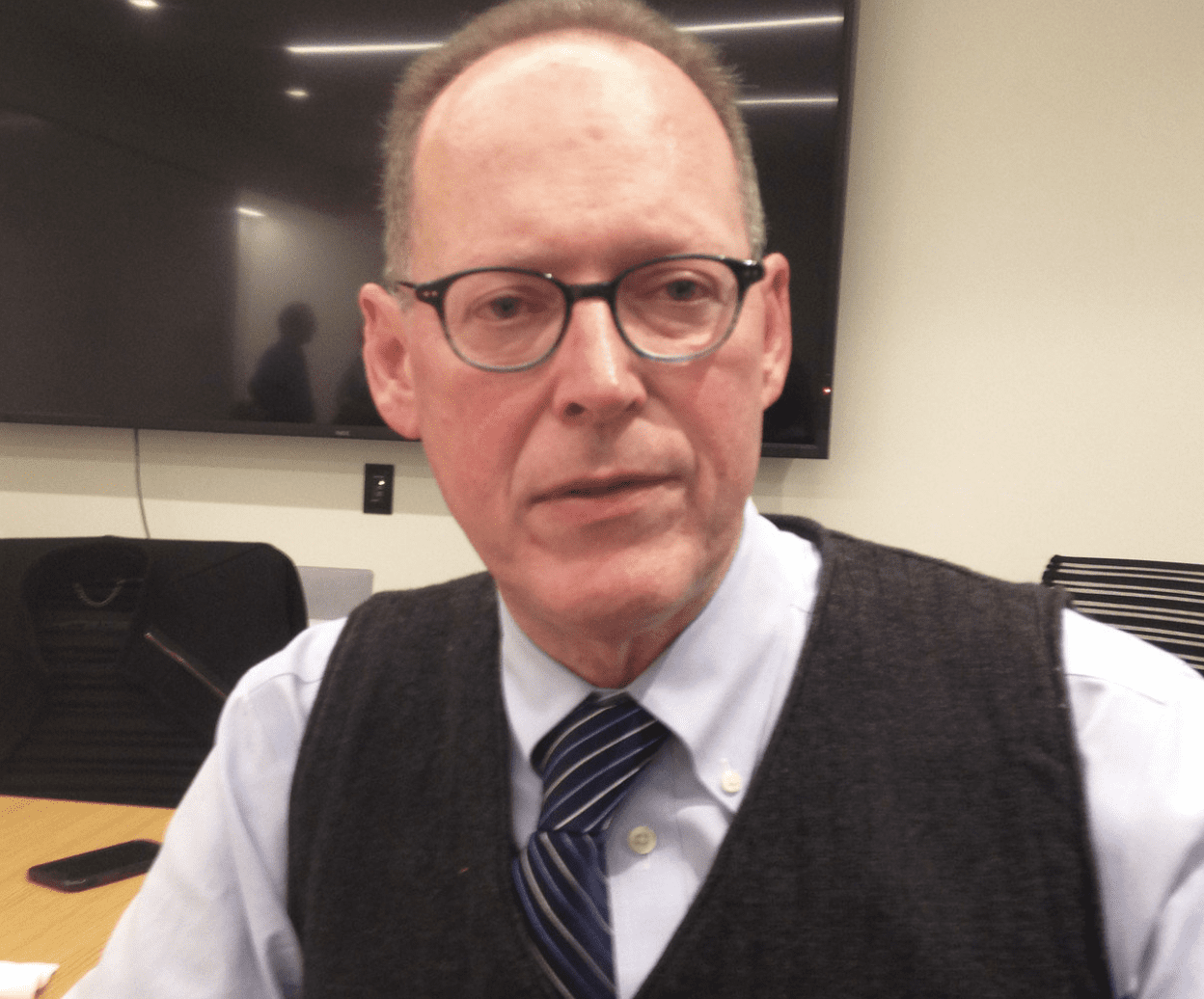

Dr. Paul Farmer is a global rock star when it comes to building public health infrastructure in the underdeveloped world. Yet, in person, perhaps reflective of a bedside manner which places great value on what the patient has to say, Farmer appeared to be much more comfortable listening rather than talking.

Dressed in a three-piece woolen suit and a blue, button-down Oxford shirt with a striped tie, Farmer could easily be mistaken for a middle-aged Harvard academic clinician rather than a radical public health practitioner. He is both.

During his recent visit to Rhode Island, Farmer often talked in a kind of shorthand, a repeated mantra, describing the building blocks of what he calls the necessary tools so often lacking in the clinical deserts where he practices as: “staff, stuff, space and systems.”

Translated, those are things such as locally trained nurses and doctors, latex gloves and sterilized syringes, buildings that are clean, with running water and electricity, and a laboratory.

His work and passion, captured in the 2003 book by Tracy Kidder, Mountains Beyond Mountains: The Quest of Dr. Paul Farmer, A Man Who Would Cure the World, is currently being carried out through nonprofits, including Partners in Health and the Division of Global Health Equity at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, in collaboration with Harvard Medical School.

Ebola: a caregiver’s disease

Farmer was in Providence on Dec. 12, 2017, to give a talk at the new Nursing Education Center at South Street Station, entitled: “The Caregiver’s Disease: Ebola and the Challenge to Nursing in West Africa.” The talk, which was sponsored by the University of Rhode Island College of Nursing, drew a crowd of more than 100 people, including many local public health practitioners and educators.

Farmer debunked much of the misguided reporting in America about Ebola in West Africa. “You saw plenty of stories about bush meat, but you didn’t see a lot of about the lack of staff, stuff, space and systems. This drive toward exoticism in an epidemic in Africa is a colonial construct,” he said. “People did not die because of strange habits; the reality is that they died because of a lack of staff, stuff, space and systems for caregivers.”

Farmer acknowledged that often, when he talked about the need for investments in public health resources in underdeveloped nations, everyone falls asleep. “Just call it Beyoncé,” he said, in a deadpan manner, describing what he called a potential winning strategy to bridge the gap between public awareness and government inaction.

Before the talk, Farmer met privately with URI faculty and administrators as well as with URI nurse practitioner students who are planning to travel to Liberia during the 2018 spring semester to help treat patients at a clinic run by Partners in Health. Elaine Parker-Williams, a doctoral student in nursing at URI, will be leading the group.

[Despite his late arrival in Providence, and a waiting audience, Farmer insisted on going around the room and having everyone introduce themselves, engaging with them personally.]

What was needed, Farmer told the students, was nurses who can nurse and doctors who can doctor: “You’re not going to become culturally competent. I’m not culturally competent in Haiti and I’ve been going there for 35 years.” He continued: “What you really need to know is to nurse,” adding that was what was missing during the Ebola crisis.

In a brief interview with ConvergenceRI before his talk, attempting to eat a quick dinner while URI administrators were literally tugging at his sleeve to get him to go begin his lecture, Farmer talked about the hopeful nature of the work.

ConvergenceRI: How do you maintain a hopeful attitude about everything that you do?

FARMER: The work is extremely hopeful, when you intervene in a place like rural Liberia, where there is no staff, stuff, space and systems, and you introduce them, and you get results. [Partners in Health is working in Maryland County in Liberia, a 20-hour drive south of the capital of Monrovia, rebuilding the health system for a population of roughly 100,000 people.]

War can mess that up. But most places are not in the middle of a war. Liberia was, but it isn’t now. So, it’s hopeful work. You have to stick with it.

ConvergenceRI: Your optimism, then, comes from doing the work?

FARMER: Yes. I’m optimistic. This work, the return on it, you see much more dramatic changes if you do this sort of work, than if you were to look at Rhode Island and Massachusetts.

Here, there are staff, stuff, space and systems; meaning there are nurses, physicians, health administrators, and health educators; there are facilities.

It can be hard [work] here when there are systems that need to be redone; that’s what is going on here in the U.S.; that’s why it is very expensive, to give poor quality medical care to poor people in a rich country.

There are maybe 50 doctors practicing in Liberia – that’s the equivalent of six doctors for all of Boston. [The number of nurses] is not much better.

And so, when you sink your time into a clinical desert, things happen, very good things happen very quickly.

Yes, it is painful in the beginning. But, good things happen quickly. It makes me optimistic, because it is optimistic work.

The talk

Farmer spoke for about 40 minutes, in a kind of rambling presentation, covering what might normally take more than two hours in a clinical setting. His lecture was peppered with interjections and asides, in a kind of running commentary, a subtext, including many wry observations.

Such as a reference to the irony surrounding the difficulty of obtaining latex gloves for caregivers treating Ebola patients in a country that once had the largest rubber plantations in the world.

Or, when showing a slide during his talk of a train moving through the countryside, saying: “I didn’t even know there were trains in West Africa. They’re not for moving people. They are for [transporting] extracted things from West Africa: bauxite, iron ore, diamonds; you name it. They are not for moving concerned clinicians around; it’s tough to move around Liberia.”

Here is an edited transcript of what Farmer had to say, with his insights into how to create what he calls “an antidote to despair.”

FARMER: It’s great to be back. I have to say, this is quite a building. It is stunning. Can I have one of these? [laughter from the audience]

I first went to Haiti in 1983. I just came back from visiting the same village where [I began working]. This work is very uplifting. I can’t imagine work that is more satisfying than going to places and getting services to people who don’t have them.

I’m not just talking about physicians and nurses but the whole spectrum of care.

By the way, keep the provost on a short leash. [URI’s provost, Donald DeHayes, had been one of the people who introduced Farmer.] When the dean of academic funding is behind you, the provost, the dean, then the faculty is free to champion the students [who want to participate] in global public health. That has been my experience at Harvard.

Ebola is a test case. How much time do we have? Three hours? [Laughter from the audience.]

I’m going to skip over the stuff that isn’t necessary.

Ebola is a virus. But when you don’t have staff, stuff, space, and medicine, you can’t take care of people. You need to have a laboratory.

[Farmer gave a brief history of Marburg, an African virus named after a German city, which had been transported in monkeys being used for research but ended up causing an 1967 outbreak in the laboratories and then in caregivers.]

In 1967, which was the dark ages of medicine and nursing for many, the majority of patients were saved, even though at first there was no idea what was the cause of vomiting, diarrhea and fever. We have a treatment for that: replacement therapy.

[Farmer described how when there had been a more recent outbreak of Marburg in what was part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and formerly known as Zaire, a former Belgian colony, the only caregivers at a rural mission hospital were sisters who spoke Flemish. “I am sure you all speak Flemish as well as I do.”]

This is a hospital with 100 beds, no doctors. These poor sisters were trying to nurse people without the staff. [Many caregivers died.]

The Marburg virus had an animal host that many people believe are fruit-eating bats. But so few people care about the disease, because it strikes quickly, usually in Africa, and almost invariably, poor people, in areas that have been struck by war.

In the first outbreak of Ebola, it was the same story, but it was a sadder story. There were no doctors.

Caregivers were reusing un-sterilized syringes and transmitting the disease.

Ebola was something not transmitted by eating bush meat, but by poor infection control in places that lacked staff, stuff, space and systems.

With Ebola, the struggle is poverty. In a clinical desert, the disease spreads [often through caregivers].

Was this really new to West Africa? I would say the answer is no. There is no evidence that this was an immunological naïve community. In fact, if you Google articles about Ebola, which I know, as a Harvard professor, I’m not supposed to advocate, you’ll find articles about the [presence of the] Ebola virus in West Africa.

It is kind of amazing to still hear claims that it was all about bush meat.

The need for staff, stuff, space, systems

[Farmer told the story of a Liberian friend of his who took eight years to finish med school, who started a small NGO and who helped to organize a conference about surgical disease in a clinical desert.]

It was all about the need for staff, stuff, space and systems for caregivers.

What’s the last act of care giving? You bury the dead. You don’t have to be Catholic to know that is one of the seven works of mercy: feed the hungry, give water to the thirsty, shelter the homeless, and bury the dead.

With Ebola, 99 percent of the deaths were in three countries – Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone. Why: because they did not have health systems.

[These countries had been ravaged by war], and after the wars, the investments made into that part of the world were needed investments, largely in peacekeeping forces, investments that were very expensive and very necessary.

But not much was invested in building national institutions and health infrastructure.

If we don’t invest in building national institutions in places like Liberia, we’re going to see problems like this again.

These places are clinical deserts compared to Haiti; trust me. If we had what we had in Haiti there, you would not have had more than 200 caregivers die just in Sierra Leone.

[Farmer told the tragic story of one caregiver, who took care of Ebola patients and survived, only to die in childbirth.]

The story of Ebola

This is the story about Ebola: it is spread in a public health desert, which is a clinical desert, where there’s no critical care [systems].

A friend of mine who survived, an American, an Infectious Disease doctor who was a caregiver, told me he lost 10 liters of fluid a day, from fever, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea.

You cannot tell children who are patients, here, drink this Pedialyte. It’s very hard to keep down 10 liters of Pedialyte when you’re vomiting.

Of course, it was a tragic situation, especially tragic for the caregivers, who knew what they were getting into, and still they intervened, trying to save family and friends, but also complete strangers.

So, too, for the Americans and other expatriates who came to help.

About false reports that people fled from doctors and hospitals

What people fled were Emergency Treatment Centers with no treatment, and Community Care Centers with no care.

The idea that they were fleeing physicians and nurses is false. They were fleeing a “disease control machinery” that was very large and very scary. It was not a rejection of modern medical care, nothing of the sort.

Dialogue around prevention and disease control

[Farmer talked about the ongoing conflict between what he termed the “disease control machinery” and the need to care for patients.]

Wear a seatbelt, right? Use a condom. Do you want me to hector you? I’d be happy to do so.

However, a lot of people are already injured, have obstructed labor, or have AIDS. That is the job of nurses and doctors that put the patient first. But that’s the first thing that goes out the door with these epidemics. It’s an inversion of priorities.

_____

To read the full article: http://newsletter.convergenceri.com/stories/an-antidote-to-despair,7096

_____

Richard Asinof is the founder and editor of ConvergenceRI, an online subscription newsletter offering news and analysis at the convergence of health, science, technology and innovation in Rhode Island.

To read more stories by Richard Asinof: https://rinewstoday.com/richard-asinof/