Search Posts

Recent Posts

- Rhode Island Weather for June 5, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 5, 2025

- RI Veterans: Did you know? 05.06.25 (Rental help, events, resources) – John A. Cianci June 5, 2025

- We Cook! Mill’s Tavern Rosemary-Lemon Statler Chicken, Yukon Golds, Haricot Vert and Dijon Demi June 5, 2025

- ICE arrests nearly 1,500 in Massachusetts. First part of “Operation Patriot” – Nantucket Current June 5, 2025

- Rhode Island Weather for June 4, 2025 – Jack Donnelly June 4, 2025

Categories

Subscribe!

Thanks for subscribing! Please check your email for further instructions.

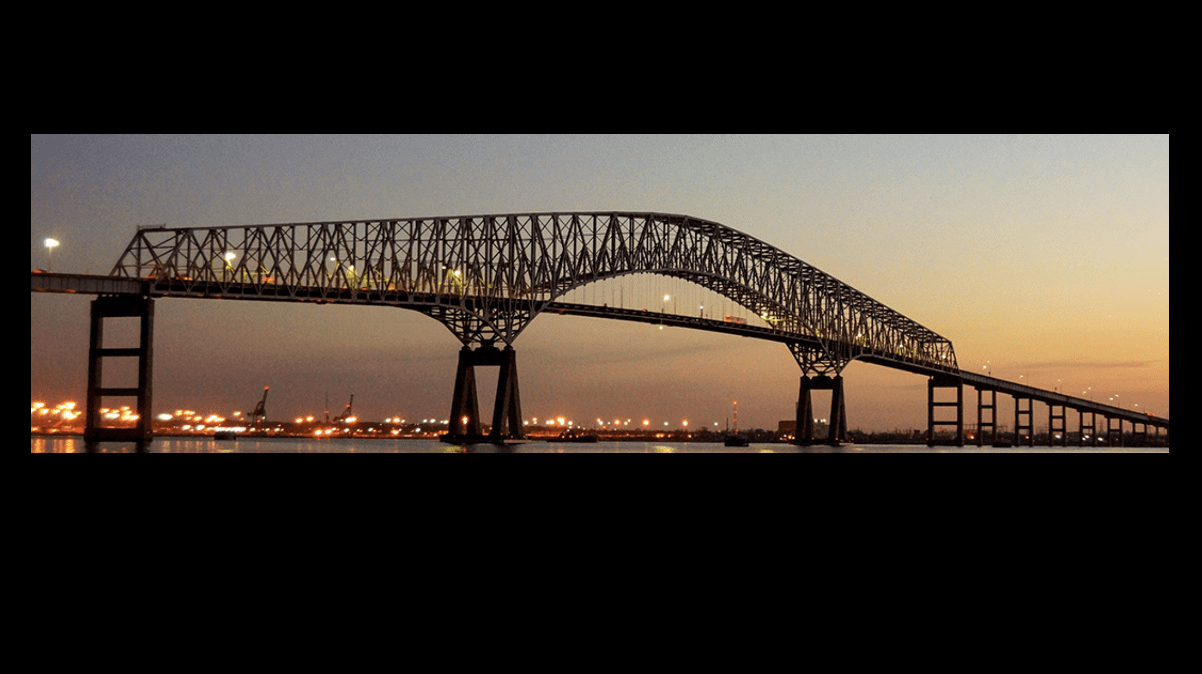

Rebuild Key Bridge as it was – David Brussat

by David Brussat, Architecture Here and There, commentary

Photo: State of Maryland

President Biden has said he will rebuild the collapsed Francis Scott Key Bridge, over the Papatsco River leading into the Port of Baltimore, at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. The bridge, completed in 1977, was hit by a freighter that lost its steering on Monday night. As of this writing, six men filling potholes on the bridge are still missing and, sadly, presumed dead. The Key was a queen of the art of infrastructure, a demonstration that utility can be beautiful. And so the president should see that it is rebuilt, as it was, to teach that very lesson.

As we all know by now, the bridge is named for Francis Scott Key, who wrote the words to what became our national anthem after seeing that our flag still flew after the failed British assault on Fort McHenry, in Baltimore Harbor, leading to the end of the War of 1812.

Curiously, the Key Bridge, 1.6 miles in length (not including some nine miles of access roads), reaching a height of 185 feet, was built to take the overflow from the Baltimore Harbor Tunnel after the latter had reached its traffic capacity. The tunnel was completed in 1957, the bridge in 1977. The bridge cost $66 million, has four lanes, to the tunnel’s two. Now it is gone, and while vehicles, including freight-hauling megatrucks, still have alternative routes in and around Baltimore. The Port of Baltimore handled 847,158 cars and light trucks last year, leading all other ports in the nation for 13 consecutive years. Cargo ships, which of course carry far more than the most humongous of trucks, will not be able to travel in or out of the harbor for many months, probably years.

Transportation Secretary Pete Buttegieg, no doubt repeating the magnificent phrase of some rhetorician long past, referred to the Key Bridge as “a cathedral of infrastructure.” That no doubt it was.

Examine the interplay of the bridge’s steel strutwork. The intricacy of its design undermines the idea that modern structure needs to be ugly. The collapse of the bridge shocked the civil engineering community, for which its design is iconic. It is the second-longest continuous-truss bridge in the United States, the third-longest in the world. The longest is the Ikitsuki Bridge, in Japan. (A truss, in engineering, is a structure whose “members are organized so that the assemblage as a whole behaves as a single object”).

Its beautiful intricacy belies its strength, and speaks to that quality vis-á-vis beauty and commodity in the famous Vitruvian triad of utilitas, firmitas and venustas (stability, usefulness, and beauty). The bridge’s firmitas withstood the stress of its utilitas – all that traffic! all those huge mack trucks thumping along its tired pavement – until three days after its 57th anniversary. Its beauty, venustas, may have been an afterthought, but it will be in the memories of all who mourn the bridge’s loss.

Engineers have been designing beautiful bridges of iron and steel for more than a century and a half. I have seen no mention in any of what I’ve read to source this post of the designer of either the bridge below (Abraham Darby?) or of the Key Bridge itself.

Key Bridge failed yesterday after suffering the massive affront of a massive cargo ship, but that does not diminish the beauty of its glorious infrastructure – which should be rebuilt to its historic design by the Biden administration.